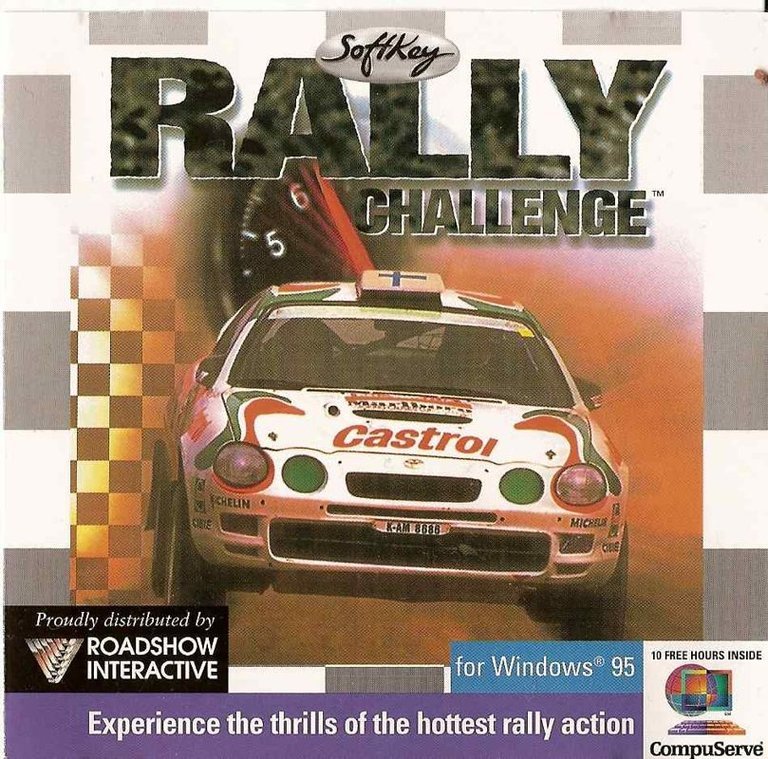

- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: SoftKey Multimedia Inc.

- Developer: Silver Lightning Software

- Genre: Driving, Racing, Simulation

- Perspective: Behind view

- Game Mode: LAN, Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Championship Mode, Off-roading, Replay mode, Track racing, Vehicle simulation

- Setting: Asphalt, Dirt, Mud, Rally stages, Snow

- Average Score: 24/100

Description

Rally Challenge is a 1997 rally racing game featuring three vehicles: the Proton Wira, Toyota Celica GT4, and Subaru Impreza WRX. Players navigate twisty rally stages with varying terrain like snow, mud, and asphalt, choosing between single stages, ghost races, or a championship season against AI or human opponents. The game supports multiplayer via serial link or network and includes a replay mode with save functionality.

Where to Buy Rally Challenge

PC

Rally Challenge Free Download

Rally Challenge Guides & Walkthroughs

Rally Challenge Reviews & Reception

myabandonware.com : Rally Challenge is little more than another nondescript, bland racing game that you’ll play only once or twice before going back to Stunts.

Rally Challenge: A Forgotten Gem of the Rally Genre?

Introduction

In the mid-to-late 1990s, the PC racing scene was a hotbed of innovation and competition, titles like Need for Speed and Colin McRae Rally vying for players’ attention. Amidst this crowded landscape, Rally Challenge emerged in 1997 as a shareware title from the tiny Australian studio Silver Lightning Software. Promising authentic rally thrills with licensed vehicles like the Subaru Impreza WRX and Toyota Celica GT4, it aimed to capture the gritty realism of off-road endurance racing. Yet, despite its ambitions, Rally Challenge has since slipped into relative obscurity, remembered only by a niche of retro gamers. This review will dissect the game’s historical context, gameplay mechanics, artistic and auditory design, and evaluate its critical reception and legacy, arguing that while flawed, it stands as a fascinating, if flawed, snapshot of late-90s rally game development.

Development History & Context

Rally Challenge was developed by Silver Lightning Software, a minuscule Australian studio comprising just three individuals: Stephen Handbury (Concept and Design), Paul Turbett (Programming), and Alex Radeski (2D and 3D Artwork). This skeletal team produced the game under the publishing umbrella of SoftKey Multimedia Inc., a company known for budget-friendly educational and PC software. The game was released as shareware—a model common at the time for reaching a broad audience before compelling them to purchase the full version. Technologically, Rally Challenge was constrained by the Windows 95 era, pushing early 3D graphics (notably a “behind view” perspective) and supporting DirectX, though compatibility issues plagued some installations. The 1997 gaming landscape was saturated with driving games, from the arcade-inspired Sega Rally to the nascent simulation-focused efforts. Silver Lightning’s ambition to create a “100% 3D action rally simulator” was bold for a small team, but their limited resources resulted in a product that, while functional, lacked the polish of larger studios’ offerings. The game’s quirky inclusion of the Malaysian Proton Wira alongside Japanese and European rally cars hints at a deliberate attempt to offer global variety, perhaps reflecting the team’s own diverse perspective.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Rally Challenge deliberately eschews traditional narrative, instead centering its story on the non-fictional, high-stakes world of professional rallying. There are no characters, cutscenes, or dialogue; instead, the game’s “plot” is defined by its licensed vehicles, authentic stage locations, and the player’s ascent through a championship season. This focus on verisimilitude is its core theme: the simulation of grueling, solitary endurance racing across international terrains. The choice of vehicles—the iconic Subaru Impreza WRX and Toyota Celica GT4—lends authenticity, as these were the dominant force in the World Rally Championship during the mid-90s. The inclusion of the lesser-known Proton Wira adds a layer of niche realism, potentially referencing the Asia-Pacific Rally Championship. The championship structure itself—the turn-by-turn racing against AI or human opponents—mirrors the actual isolated nature of rally stages, where drivers compete against the clock rather than bumper-to-bumper. This thematic commitment to realism extends to the game’s most innovative feature: the Custom Notes editor. Allowing players to create and record their own navigator commands in .wav format (with a default Australian accent), it directly replicates the co-driver’s role in real rallying, transforming the player-car interface into a simulated team dynamic. The absence of a traditional narrative is thus not a flaw but a thematic choice, emphasizing the sport’s mechanical and strategic over cinematic drama.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The core gameplay loop of Rally Challenge revolves around three primary modes: Single Stage, Ghost Race, and Championship Season. The Single Stage mode allows players to tackle one of nine international courses, ranging from Sweden’s snow-swept roads to Greece’s dusty mountain passes. Championship mode strings these stages together, pitting the player against up to nine AI or human opponents in a points-based competition. A key technical limitation is the “turn-by-turn” system: races are executed sequentially without real-time AI vehicles on track, a concession to the era’s processing power. This creates an abstracted competitive experience focused on time trials rather than dynamic wheel-to-wheel action. The physics and handling are serviceable but unspectacular. While noted as “reasonably realistic” for the time, they lack the nuanced weight transfer and damage modeling of later titles like Colin McRae Rally. Cars respond predictably to inputs, with terrain (snow, mud, asphalt, gravel) affecting traction, but the sensation of speed and danger often feels muted. The customization and progression are minimal; players choose from three pre-tuned cars with no upgrades or tuning options. The standout system is the Custom Notes editor, a remarkable feature for a 1997 shareware title. It lets players record and synchronize audio cues (e.g., “Left 100, tricky”) to specific track points, played back by a simulated navigator. This adds a strategic layer, demanding memorization and adaptation. Multiplayer, supporting 1-8 players via LAN or null-modem cable, offered a competitive edge but was hindered by the turn-by-turn format. Overall, the gameplay is mechanically solid but lacks the depth or excitement to sustain long-term engagement.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Rally Challenge’s greatest strength lies in its world-building and environmental variety. The nine stages are set across distinct countries—Sweden, Indonesia, Australia, Greece, France, and others—each with meticulously researched terrain types and scenery. From the icy Scandinavian forests to the sun-baked Greek hills and the tropical humidity of Indonesia, the stages offer a global tour seldom seen in contemporary games. This diversity in surfaces (snow, mud, asphalt, gravel) directly impacts gameplay, demanding different driving approaches. Visually, the game leverages early 3D polygonal models for cars and environments, with mixed results. The cars are recognizable but blocky, while the landscapes—though limited in draw distance—effectively convey each location’s atmosphere through texture work and color palettes. The sound design is equally ambitious. The engine and tire sounds are functional if unremarkable, but the audio notes system is a triumph of immersion. The default Australian-accented navigator, combined with the ability to create custom .wav files, adds a layer of authenticity rarely replicated in the genre. The crunch of gravel on snow or the skid of tires on mud enhances the tactile feedback, even if the overall audio fidelity is modest. While the art style won’t win awards, the cohesive international presentation and attention to rally-specific details (e.g., trackside banners, stage signage) create a convincing, if pixelated, rally world.

Reception & Legacy

Upon release, Rally Challenge received a lukewarm reception. Player scores on MobyGames paint a grim picture, with an average rating of just 1.2 out of 5 based on three submissions. MyAbandonware’s community score is more generous at 4.16/5 (19 votes), but the accompanying review from “HOTUD” is damning, calling it “decent… but not particularly special” and a “nondescript, bland racing game.” Critics praised its exotic track locations (especially underrepresented ones like Indonesia) and the innovative Custom Notes editor, but lamented its shallow physics, lack of replayability, and generic presentation. Commercially, it faded quickly against AAA competitors like Network Q RAC Rally Championship and the burgeoning Colin McRae series. Its legacy has been one of historical footnote. While it pioneered community-driven content with its notes editor and offered global stage variety, it lacked the technical prowess or depth to define the rally genre. Silver Lightning Software disbanded after this project, and its members contributed to other niche titles (e.g., Ancient Evil). The game’s most enduring legacy is its cult appreciation among retro abandonware enthusiasts, who value it as a time capsule of 90s shareware ambitions rather than a classic. It remains a cautionary tale of how licensed cars and international flair cannot compensate for undercooked gameplay.

Conclusion

Rally Challenge is a classic case of a game with noble ambitions constrained by limited resources and an unforgiving market. It excels in thematic authenticity, offering a credible rally simulation through its licensed cars, international stages, and the ingenious Custom Notes system. However, its turn-by-turn racing, rudimentary physics, and lack of long-term engagement prevent it from rising above mediocrity. For historians, it’s a fascinating artifact of the shareware era and the early days of PC rally gaming, showcasing both the creativity and limitations of small Australian developers. For gamers, it’s a niche curiosity best revisited through abandonware archives. While it won’t dethrone Colin McRae Rally or Sega Rally in the annals of racing greatness, Rally Challenge deserves recognition as a flawed but earnest attempt to capture the spirit of rallying during a pivotal moment in video game history. It stands as a reminder that innovation can bloom in the unlikeliest of digital gardens, even if the fruits are not always sweet.