- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Ubi Soft Entertainment Software

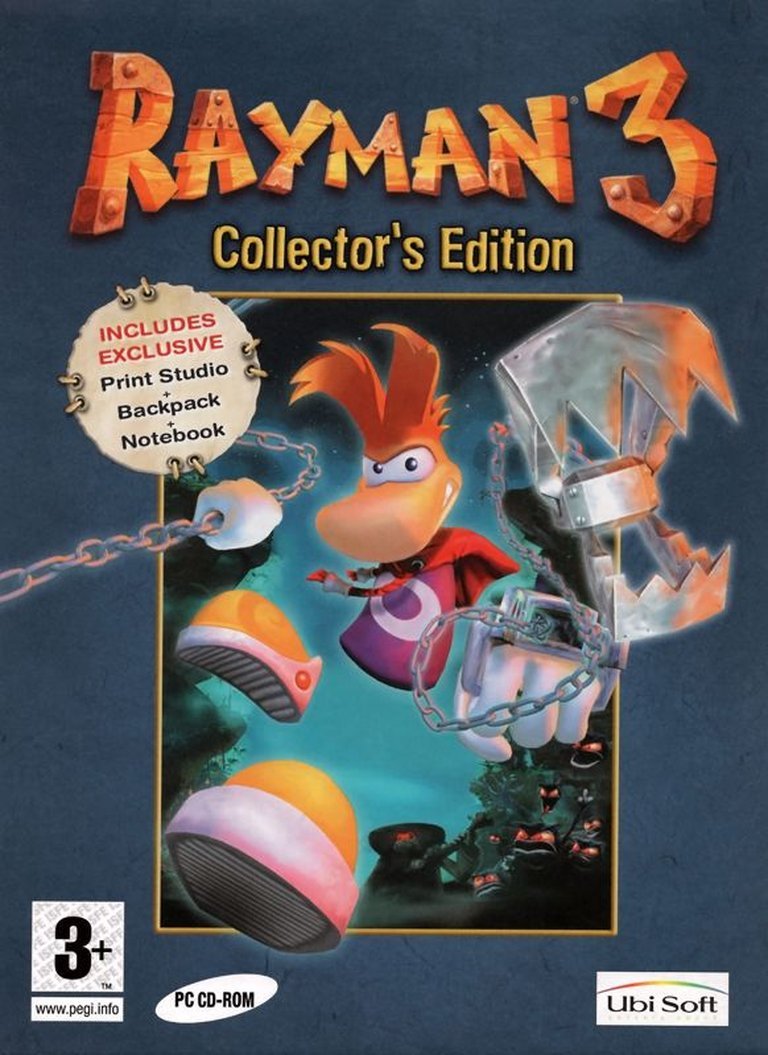

- Genre: Special edition

- Average Score: 77/100

Description

Rayman 3: Hoodlum Havoc (Collector’s Edition) is a platform game where Rayman embarks on a quest to stop the evil Black Lum André from conquering the world with his hoodlum army, while also finding a cure for his friend Globox after he accidentally swallows André, all set in a vibrant, whimsical fantasy universe filled with quirky characters and challenging levels.

Rayman 3: Hoodlum Havoc (Collector’s Edition) Mods

Rayman 3: Hoodlum Havoc (Collector’s Edition) Guides & Walkthroughs

Rayman 3: Hoodlum Havoc (Collector’s Edition) Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (77/100): The scenery looks so stunning that it tempts you to explore every corner.

Rayman 3: Hoodlum Havoc (Collector’s Edition) Cheats & Codes

PlayStation 2 (CodeBreaker, NTSC-U)

Enter codes via CodeBreaker or GameShark device.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| FA7A006E 32C1F1B9 | Mastercode for Versions 1-5 |

| 9A944468 18469B76 | Mastercode for Versions 6+ |

| 2B9F3883 00000029 | Unlimited Health |

| 1A950A3F 0000FFFF | Faster Score Gain |

| 2A6F787C 000F423F | Max Score |

| DAD60D09 B2FE1544 | Moon Jump |

| 2BE7368A 413FFFFF | Moon Jump |

Xbox

Press X, Y, X, R, L, Back, White during gameplay.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| X, Y, X, R, L, BACK, WHITE | Big heads |

PC

Type REVERSE during gameplay.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| REVERSE | Screen mirrored |

Rayman 3: Hoodlum Havoc (Collector’s Edition): A Frenetic, Flawed, and Fascinating Cul-de-Sac in Platforming History

Introduction: The Last Hurrah of a Limbless Legend

In the pantheon of 3D platformers, Rayman 3: Hoodlum Havoc occupies a curious and compelling space. Released in 2003 at the zenith of the genre’s popularity, it arrived as the final installment in the series’ classic 3D era before the franchise’s comedic reinvention via the Raving Rabbids. For Ubisoft’s Montreal studio, it represented a confident, if straining, attempt to evolve the vibrant, dreamlike platforming of Rayman 2: The Great Escape into something more action-oriented and densely packed. The limited-run Collector’s Edition for Windows, a retail oddity bundled with a print studio application, a branded notebook, and a string bag, serves as a physical totem for this ambitious, messy, and ultimately transitional chapter. This review will argue that Rayman 3 is a game defined by magnificent aesthetic ambition and innovative systemic hooks, yet often undermined by its own frantic design philosophy and a narrative that, while clever, struggles to harmonize its tonal shifts. It is not the timeless masterpiece of its predecessor, but it is a fascinating, deeply idiosyncratic artifact of its time—a platformer that tried to be an arcade brawler, a scoring-obsessed challenge, and a surreal comedy all at once, succeeding spectacularly in flashes but fraying at the edges under the weight of its own ideas.

Development History & Context: A Studio at a Crossroads

Rayman 3 emerged from a period of significant growth and internal restructuring at Ubisoft. The primary development was handled by Ubi Soft Paris, with Ubi Soft Shanghai assisting on the GameCube and HD versions, and Ludi Factory porting to Game Boy Advance. This multi-studio approach, common for major cross-platform releases of the era, inevitably led to some variance in polish, though the core 3D versions maintained a strong visual identity. The project was led by producer Ahmed Boukhelifa and designer Michael Janod, with David Neiss handling the writing. The game’s development occurred in the shadow of Rayman 2‘s critical darling status and amidst a hyper-competitive platformer landscape dominated by Nintendo’s Mario and Rare’s Banjo-Kazooie series.

Ubisoft invested heavily, with a reported $4 million marketing budget, signaling a major push to cement Rayman as a premier console mascot. Technologically, the game utilized a refined version of the engine powering Rayman 2, allowing for more detailed geometry, vibrant lighting effects, and smoother framerates across the new generation of hardware (GameCube, PS2, Xbox). A key constraint was the need to support all platforms with a consistent core experience, a challenge that sometimes manifested in varying performance and texture resolution. The era’s technological ceiling also meant that the game’s famously dense, layered environments and chaotic Hoodlum battles could occasionally tax the hardware, leading to occasional frame-rate dips, particularly on the PlayStation 2. The development team’s vision was clear: to create a “more adult,” action-heavy Rayman, a direction subtly hinted at by the casting of John Leguizamo as the voice of Globox—a choice that injected a specific, hyperactive comedic energy into the series.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Lum That Launched a Thousand Hoodlums

The plot of Rayman 3 is a masterclass in metafictional whimsy, albeit one that occasionally gets lost in its own convoluted machinery. The inciting incident is a brilliant, self-referential flashback: Rayman, trying to entertain a sleeping Globox with shadow puppets, inadvertently terrifies a Red Lum, transforming it into the first Black Lum, André. This establishes the game’s core ironic theme—that thoughtless, playful actions can birth catastrophe. André’s goal is superficially classic villainy: taint the world’s heart to create a Hoodlum army. Yet the execution is pure Rayman surrealism. The Hoodlums themselves are bleached, scarecrow-like creatures made from stolen animal hair, a visual gag that satirizes militaristic conformity. Their quest to retrieve their “Lord” (André) from Globox’s stomach frames the entire adventure as a bizarre, gastro-centric rescue mission.

The narrative’s structure is episodic, sending Rayman through a series of wildly imaginative biomes (the Moor of Mad Spirits, the Summit of Fury) to find a “cure.” This leads to the infamous three doctors sequence—a slapstick marathon where Otto Psi, Romeo Patti, and Art Rytus attempt to purge André from Globox using his body parts as musical instruments. It’s a highlight of absurdist writing but also a pacing bottleneck, feeling like a prolonged joke that stalls momentum. The second act introduces Reflux, a Knaaren warrior, and the Leptys mythology, shifting the stakes to a cosmic scale that feels both grandiose and slightly unearned. The resolution, where Rayman uses the Leptys’ power to make André laugh (turning him back into a Red Lum), perfectly bookends the origin story— laughter, not fear, is the antidote. However, the final, melancholic exchange between Rayman and Globox, where the latter expresses missing André, introduces a poignant, if unsettling, note about the nature of evil and companionship that the game’s generally zany tone isn’t quite equipped to explore deeply.

Tone is the game’s most volatile element. It swings from the horror-tinged atmosphere of the Moor (with its hanging cages and spectral figures) to the broad, cartoonish antics of Globox (voiced with frantic brilliance by Leguizamo) to the deadpan surrealism of Murfy’s exposition. This inconsistency is a strength and a weakness: it makes the world feel unpredictably vast and weird, but it can make emotional beats feel ungrounded. Thematically, it touches on creation myths, the consequences of carelessness, and the blurred line between hero and inadvertent villain, but it coats these ideas in such a thick layer of humour that they often function as background texture rather than focal points.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Combo, Power-Ups, and Perpetual Motion

The gameplay of Rayman 3 represents a decisive pivot from Rayman 2‘s exploration-heavy design toward a combat-and-score-centric loop. This is its most defining and divisive innovation: the arcade-style scoring and “Combo Mode” system. Every action—punching an enemy, collecting Lums, breaking a cage—awards points. Scoring triggers a temporary “Combo Mode” where all subsequent point gains are multiplied and stored separately. If scoring stops, the combo ends and the bonus points are added to the total. This transforms every level into a energetic puzzle of maintaining momentum. Using one of the five Laser Detergent power-ups (Vortex, Heavy Metal Fist, Lockjaw, Shock Rocket, Throttle Copter) doubles all point values, incentivizing their strategic use not just for traversal or combat, but for maximizing scores. Critically, taking damage deducts a point, making reckless aggression costly. This system ingeniously ties risk/reward to the core platforming, rewarding stylish, continuous play. Points unlock hidden bonus worlds and content, giving the game significant replay value beyond mere completion.

However, this design shift has consequences. Combat is no longer occasional; it is relentless. Hoodlum armies populate almost every inch of the environment, employing predictable but aggressive attack patterns. Rayman’s long-range punch, while satisfying, requires lock-on mechanics that can feel imprecise in crowded scenes. The game’s difficulty often stems from overwhelming numbers rather than complex platforming challenges, which can lead to a feeling of grind rather than skill-based progression. The power-ups are creatively designed and essential for progression and scoring, but their temporary nature means the core abilities can feel inconsistent. The Lockjaw, in particular, is a standout gadget, enabling clever traversal and electrifying enemy disposal, showcasing the team’s inventive spark.

The health system, based on collecting Red Lums and freeing Teensies (six freed Teensies increases max health), is straightforward but less engaging than the scoring mechanic. The multiplier-driven unlockables are a highlight, revealing some of the game’s funniest FMV shorts and mini-games, which reward mastery handsomely. The UI cleanly communicates the combo meter and score, but the constant point ticker can become visual noise during intense battles.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Vibrant, Overstuffed Canvas

Visually, Rayman 3 is a triumph of coherent, fantastical art direction. The worlds are less biologically organic than Rayman 2‘s and more like bizarre, themed playsets: the Moor of Mad Spirits is a gothic swamp of hanging cages and ghostly trees; the Summit of Fury is a dizzying, icy climb with howling winds; the Land of the Livid Dead is a subterranean nightmare of flesh-toned caverns and pulsating organs. The color palette is electric—deep purples, sickly greens, and vibrant pinks dominate, creating a world that feels both dangerous and invitingly cartoonish. Character design is exaggerated and expressive, from the ragged, panicked Hoodlums to the monolithic, silent Knaaren. The use of lighting and particle effects (sparks from punches, glowing Lums) was cutting-edge for its time and still holds a charming, slightly plastic sheen that complements the unreal atmosphere.

The sound design and score are inseparable from the game’s identity. Composed by Plume, Fred Leonard, and Laurent Parisi, the soundtrack is a brilliant fusion of orchestral whimsy and funky, trip-hop beats. Tracks like “The Moor of Mad Spirits” use disparate instrumentals and dissonant chords to create unease, while “The Summit of Fury” employs driving percussion and soaring strings to inspire determination. It dynamically shifts with gameplay, swelling during combat and receding during exploration. The voice acting, a major step up from the gibberish of Rayman 2, is a defining feature. Leguizamo’s Globox is a whirlwind of impropanic anxiety and loyalty. The Hoodlums chatter in a high-pitched, militaristic slang, and André is a smoothly sinister presence. Murfy’s dry, administrative commentary provides perfect counterpoint. The audio presentation is arguably the element that most successfully sells the game’s unique, slightly unhinged comedic tone.

Reception & Legacy: A Solid Success, a Faded Icon

Upon release, Rayman 3 was met with generally positive reviews, though the consensus often noted it was a step below its predecessor. Aggregate scores hovered in the high 70s to low 80s across platforms (Metacritic: 77 on GameCube, 76 on PS2, 74 on PC). Critics widely praised its stunning visuals, humor, presentation, and the inventive combo system. Common criticisms targeted the excessive, sometimes tedious combat, the occasional camera issues, and a feeling that it lacked the pure, unadulterated platforming magic of Rayman 2. It was a commercial success, selling over 1 million copies by the end of March 2003, validating Ubisoft’s investment.

Its legacy is complex. For a generation, it stood as the last “mainline” 3D Rayman game, a capstone on an era. However, the explosive, family-friendly success of Rayman Raving Rabbids in 2006 utterly reshaped the franchise, casting Rayman 3 as the end of one style and the precursor to another. In the years since, its reputation has solidified among fans as a cult favorite. Re-releases on GOG, Steam, PlayStation Network, and Xbox Live Arcade (as Rayman 3 HD) have introduced it to new audiences who appreciate its bizarre charm and intense score-chasing gameplay. User reviews on platforms like GOG (4.3/5) and Metacritic (User Score ~8.2) are often more effusive than the contemporary critical response, with players championing its depth, humor, and memorable power-ups.

It is not as influential as Super Mario 64 or as universally beloved as Rayman 2. Its core mechanic—the combo-based scoring—was not widely adopted by the genre. Instead, its legacy is as a brilliant, idiosyncratic dead-end. It proved that a platformer could be a frantic arcade score-attack game, but the market ultimately preferred pure platforming or pure combat. It also remains the last Rayman game with a narrative that, for all its chaos, feels like a coherent, if wild, Rayman story, before the series embraced pure, vignette-based comedy.

Conclusion: The Collector’s Curse and the Game’s Fate

The Collector’s Edition itself is a poignant artifact. Bundling the game with a “Print Studio” application for making custom artwork and physical tchotchkes (a notebook, a bag) speaks to an era where PC games often came with ambitious, tangible extras—a practice now largely relegated to special editions of massive RPGs or shooters. For Rayman 3, it feels like a last-ditch effort to create a “complete package” for a game that, in its digital core, is a whirlwind of ideas struggling for cohesion.

Ultimately, Rayman 3: Hoodlum Havoc is a game you must play to understand the ambition of mid-2000s platforming. Its highs are dizzying: the visual splendor of its worlds, the relentless joy of a perfect combo run, the sheer audacity of its plot, and the timeless charm of its sound design. Its lows are equally tangible: combat that feels mandatory rather than fun, a narrative that stumbles in its third act, and a certain lack of the ethereal platforming purity of its predecessor.

It is not the best Rayman game, but it is perhaps the most Rayman game—overstuffed, weirdly pitched, emotionally transparent in its absurdity, and technically impressive for its time. The Collector’s Edition serves as a fitting metaphor: a slightly unwieldy, proudly physical package containing a digital experience that is just as complex, flawed, and unforgettable. In the history of platformers, it is a vibrant, chaotic footnote—a game that swung for the fences with a bat full of power-ups and narrative gags, hit several home runs, but also struck out looking at a curveball it never saw coming. For the enthusiast, it is an essential, messy masterpiece. For the casual observer, it remains a fascinating “what if” of a franchise that took a sharp, Rabbids-shaped turn immediately after.