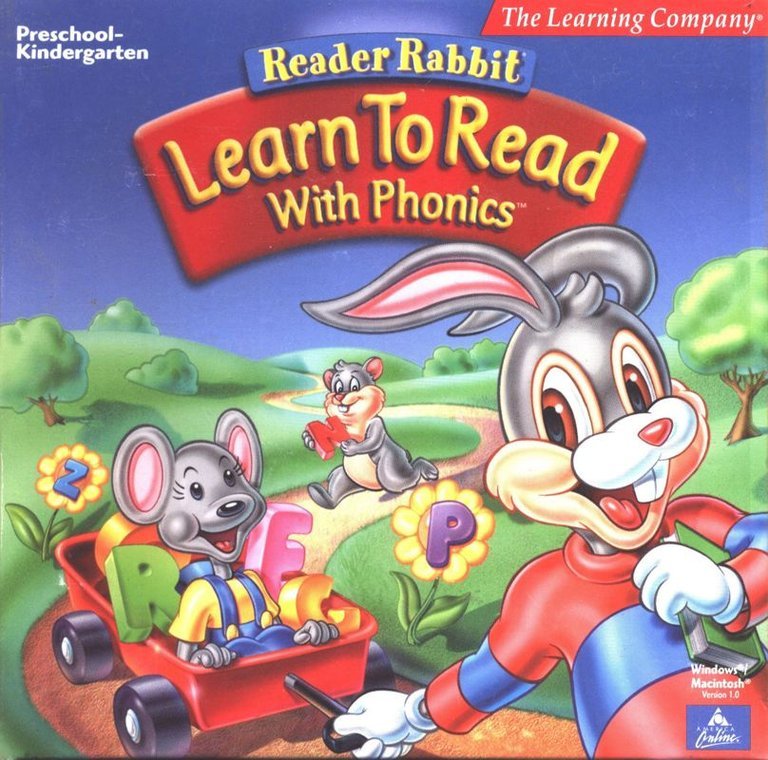

- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Learning Company, Inc., The

- Developer: Learning Company, Inc., The

- Genre: Educational

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Mini-games

- Setting: Wordville

Description

Reader Rabbit: Learn to Read with Phonics is an educational game designed for children aged 3 to 6, where players assist Matilda and Reader Rabbit in restoring words to Wordville after Matilda inadvertently wishes them away due to her inability to read. The game employs phonics-based learning through mini-games that teach letter sounds and review them with interactive stories, offering two modes: ‘Road to Reading’ for a structured, map-based progression and ‘Pick and Play’ for direct access to activities, making it suitable for both preschoolers and older beginners.

Gameplay Videos

Reader Rabbit: Learn to Read with Phonics Guides & Walkthroughs

Reader Rabbit: Learn to Read with Phonics: A Digital Phonics Odyssey

Introduction: The Rabbit Hole to Literacy

In the vast museum of video game history, certain titles are enshrined not for their polygon counts or commercial blockbuster status, but for their profound, formative impact on millions of players. For a generation of 1990s and early 2000s children, the cheerful,Algebraic visage of Reader Rabbit was as iconic as Mario or Sonic. Reader Rabbit: Learn to Read with Phonics, released in 2000 for Windows and Macintosh, stands as a pivotal, if complex, artifact from the zenith and twilight of a beloved era. It is a game that encapsulates the noble educational ideals, the sophisticated pedagogical design, and the looming corporate shadows that defined the golden age of “edutainment.” This review argues that Learn to Read with Phonics is not merely a superior entry in a long-running franchise but a masterclass in adaptive, phonics-based literacy instruction disguised as a vibrant adventure. It represents the apex of The Learning Company’s design philosophy—a seamless blend of narrative motivation, systematic skill-building, and playful mini-games—while simultaneously serving as one of the last gasps of a once-dominant genre before the collapse of its corporate patron and the disruptive rise of the internet.

Development History & Context: The House of Cards

To understand Learn to Read with Phonics, one must understand The Learning Company (TLC), a studio with a lineage as storied and turbulent as any in gaming. The company’s roots trace back to 1984 and the visionary, education-focused work of Leslie Grimm and Ann McCormick, who pioneered a “lead kids towards the answer” philosophy that rejected punitive, drill-and-kill software. Their 1984 debut, Reader Rabbit and the Fabulous Word Factory, created the franchise’s template: a charming world, relatable animal characters, and games that taught reading through play.

By the late 1990s, TLC was an edutainment juggernaut, owning not just Reader Rabbit but also Carmen Sandiego, Oregon Trail, and Zoombinis. However, a series of blunders was underway. In 1995, the cost-cutting corporate raider Kevin O’Leary (of future Shark Tank infamy) acquired TLC via his SoftKey conglomerate, slashing R&D budgets in favor of aggressive marketing and price wars. The quality of new titles began to stagnate as foundational research was deprioritized. Then came the calamitous 1998 acquisition by toy giant Mattel for $3.6 billion, a deal later deemed one of the worst in corporate history. Mattel, seeking to synergize toys and software, had overpaid for a company whose value was largely账面 inflated by its acquisition-heavy, low-R&D model.

Reader Rabbit: Learn to Read with Phonics was developed and released during this precipice. It is, as noted in the Fandom wiki, “the last game in the Reader Rabbit franchise to be released by The Learning Company (formerly SoftKey) before it was sold to Mattel,” and “the last known Reader Rabbit game to be compatible with Windows 3.1.” Technologically, it was a product of its time: a CD-ROM title leveraging the medium’s capacity for colorful graphics, voice acting, and multimedia, but built on architectures soon to be obsolete. It was also a compilation title, pairing 1999’s Reader Rabbit’s Learn to Read with the 1997 Reader Rabbit’s Reading 1 as a bonus. This bundling strategy reflected TLC’s shifting commercial model under SoftKey/Mattel—emphasizing comprehensive “systems” (as seen in the included workbook and flash cards of the Complete Learn to Read System compilation) to justify higher price points in a saturated market.

The gaming landscape of 2000 was one of transition. The educational software boom of the early CD-ROM era was peaking, but the internet was beginning to fragment the market with free alternatives. Learn to Read with Phonics thus feels like a beautifully polished sunset—a final, robust expression of a proven formula before the storm.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Wish Gone Wrong in Wordville

The game’s narrative is a clever, self-contained parable about the value and necessity of language. The plot, detailed in the MobyGames and Fandom descriptions, centers on Matilda the Mouse (known as Mat). Her motivation is immediately relatable: she cannot read the signs at the carnival, a frustration that renders her excluded from the fun. In a moment of pique, she encounters a magical Wish Machine and wishes for all the words in Wordville to vanish.

This is no mere whimsical MacGuffin. The wish’s immediate, chaotic consequence—a world rendered silent and illegible—creates genuine stakes. Mat’s subsequent regret and quest to undo her mistake form a classic narrative arc of consequences, responsibility, and redemption. She is not a passive recipient of learning but an active agent who must fix the problem she caused, a powerful thematic reinforcement for a child player: literacy is not just a skill, but a tool to repair one’s world.

Her journey is supported by a delightful ensemble cast. Reader Rabbit serves as the steadfast, capable guide. The Performing Hamsters—Nellie, Calhoun, Lefty, and Milton—are introduced as carnival performers whose skills (singing, acrobatics) are rendered useless without words, making them sympathetic allies. Their integration into the “Letter Lands” as guides and hosts is a brilliant narrative mechanization. Each “Land of the Letter X” becomes their domain, tying the phonics instruction directly to characters the player cares about. The Wish Machine itself, voiced with a mix of whimsy and gravity by Terry McGovern, acts as both antagonist and plot device, its departure setting the quest in motion.

The story is delivered through animated sequences and, crucially, the interactive storybooks that cap each Letter Land section. These aren’t passive readings; they often require the child to “fix” the story by inserting the correct learned words or find objects on the page. This meta-narrative—the power to correct and complete a story—mirrors Mat’s larger quest and instills a sense of narrative agency. The theme is clear: reading is the key that unlocks story, community, and problem-solving.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Architecture of Phonics

Learn to Read with Phonics is architecturally bifurcated, offering two distinct modes that cater to different learning stages and play preferences, a design choice reflecting TLC’s research-backed, adaptive philosophy.

1. Road to Reading (The Structured Curriculum):

This is the primary adventure mode. The player navigates a linear map of Wordville, which has been fractured into 26 “Letter Lands” (one for each letter, including ‘Qu’). The progression through each land is a carefully scaffolded lesson loop:

* Game A (Learn the Sound): A mini-game introduces the primary sound of the letter (e.g., ‘M’ as in Mmmmm!). Activities vary and include:

* Costume Creator: A sight-word matching game where children dress hamsters by selecting doors labeled with target words.

* Bubble Blend: Focuses on word blends (e.g., ‘ap’ in ‘Cap’). Children combine bubble parts to form words.

* Music Labeler: A spelling-focused task where missing letters in words must be placed correctly.

* Sorter Magic: Teaches suffixes by sorting words into a magic box or trash bin based on their endings.

* The Great Race: A word recognition race where choosing the correct word moves a hamster forward.

* Game B (Review the Sound): A second, different mini-game reviews the same letter sound in a new context, reinforcing learning through variation.

* Storybook: The player reads (or is read to) a short book utilizing words with the target sound. Often, the book is “broken”—words are missing or scrambled—and the player must correct it using their new knowledge. This application step is critical for transfer.

This loop is a masterpiece of instructional design. It follows the explicit, systematic phonics model: Introduce → Reinforce → Apply. The map provides a clear, visual sense of progression and accomplishment. The Fandom wiki meticulously lists each Letter Land, its associated book, and the reading level (1-5), showing a deliberate increase in complexity. For example, the ‘M’ land has Mmmmm! (Level 1), while ‘Qu’ has The Story Quilt (Level 5).

2. Pick and Play (The Sandbox):

This mode is a practice paradise. It grants immediate, unrestricted access to all 26 Letter Lands’ mini-games, all storybooks, and all eight included songs (like “If You Read” and character-specific tunes). As the MobyGames description states, this is “recommended for toddlers and preschoolers, while ‘Road to Reading’ is designed for older children.” It allows for open-ended exploration, replay of favorite activities, and focused practice on trouble spots without the pressure of narrative progression.

Included Bonus: Reader Rabbit’s Reading 1

The inclusion of the 1997 Reader Rabbit’s Reading 1 as a bonus disc is significant. It represents the immediate precursor to this title, a more traditional “Interactive Reading Journey” with 20 Letter Lands (mostly consonants and blends) and two books per land. Its presence offers a broader curriculum and a glimpse into the evolutionary path that led to the more streamlined, phonics-specific 2000 title.

Systems & UI:

The user interface is intuitively designed for a pre-literate or early-reader audience. Icons are large, colorful, and contextually clear. The “Progress Report” screen (seen in screenshots) provides a motivating visual overview of completed Letter Lands. The entire experience is guided by a consistent, gentle narration (Terry McGovern) and character voiceovers. There is no punitive failure state; incorrect answers are met with encouraging feedback and retry options, aligning with the series’ long-stated philosophy of leading, not punishing.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Charm of Wordville

The world of Learn to Read with Phonics is Wordville, a place where language is literally the fabric of reality. Its aesthetic is a product of the late-90s/early-2000s hand-drawn, digitized style that defined TLC’s output. According to Wikipedia, artist Fred Dianda was Lead Artist for later titles, with contributions from veterans like Gerald Broas (hand-drawn line art) and Marc Diamond (storybook illustrations). The result is a world that is:

- Warm & Handcrafted: Backgrounds have a textured, painted feel. The Letter Lands are themed environments (e.g., a musical stage for ‘M’, a farm for ‘P’, a pond for ‘O’) that visually reinforce the letter’s sound and vocabulary.

- Character-Driven: The designs of Reader, Mat, and the Performing Hamsters are expressive and consistent. The hamsters, in particular, are a joyful addition, their diverse personalities (the diva Nellie, the goofy Milton) given voice and mini-game integration.

- Narratively Integrated: The transition from the carnival intro to the map of Wordville is seamless. The world doesn’t just look like a game menu; it feels like a storybook setting with cause and effect.

Sound Design is where the game truly sings (quite literally). Composer Scott Lloyd Shelly’s work, noted in Wikipedia as a source of pride for the team, provides catchy, thematic melodies for each area. The songs are not just ditties; they are diegetic character expressions (Nellie’s Song, Calhoun’s Song) that deepen personality and provide memorable hooks for letter sounds. The voice acting, listed on IMDb, is uniformly excellent—clear, friendly, and full of character, especially McGovern’s versatile narrator/Wish Machine. The soundscape of bubbling blends, sorting magic, and hamster cheers turns phonics practice into a sensory-rich party.

Reception & Legacy: A Peak and a Precipice

Critical Reception at Launch:

Learn to Read with Phonics was met with the strong, consistent praise that the Reader Rabbit brand had earned over 15 years. MobyGames records its sole critic review from FamilyPC Magazine as 88/100, which lauded its “all-in-one approach” of software, workbooks, and flash cards, calling the package a “bargain.” This assessment was typical. The Reader Rabbit series, by the late 90s, was an “educational staple in schools and homes” with a “long tradition of quality educational software,” as The New York Times noted in 2002. It had won over 175 awards by 2017, including numerous Parents’ Choice Gold Awards and Technology & Learning accolades. Its success was commercial: the series had moved 25 million copies by 2002, with the original Word Factory hitting the Billboard charts in 1985.

Place in the Series & Historical Context:

This title is a key evolutionary link. It directly refines the “Letter Land” system pioneered in Interactive Reading Journey but applies it systematically to all 26 letters and core phonics sounds, creating a complete foundational reading program. It is also, as the Fandom wiki exhaustively documents, a game of lasts:

* Last TLC-developed Reader Rabbit game before the Mattel sale.

* Last major PC release compatible with Windows 3.1.

* Last game to use the original, pre-“treehouse” title screen sequence in its initial compilation form.

These “lasts” are not trivial. They mark the end of an era of dedicated, deep PC educational software development from the franchise’s original creators.

The Collapse & Legacy:

The game’s 2000 release was barely a year before Mattel’s catastrophic $3.6 billion investment turned into a $27 million fire sale. As detailed in The Outline’s investigative piece, the damage was profound. Industry veteran Bernard Stolar stated TLC “killed the educational software industry… because there was so much product out there and all of the product was crap,” a hyperbolic but pointed critique of the overproduction and quality dilution that followed the SoftKey model. The internet, with its free resources, delivered the final blow. Sales for home educational software plummeted from $498M in 2000 to $152M by 2004.

In this context, Learn to Read with Phonics is a harbinger of the genre’s end and its most refined artifact. It uses the accumulated wisdom of 16 years of design—the A.D.A.P.T. learning technology mentioned in Wikipedia, the character-driven narratives, the song-and-game integration—to create a product of remarkable depth. Yet, it was released into a market that would soon vanish.

Its legacy is dual. First, as a pedagogical touchstone: for those who played it, the concepts of “Letter Lands,” phonics blending, and interactive story correction are permanently linked to the joy of discovery. Second, as a cultural artifact: it represents a lost world of thoughtful, expensive, immersive CD-ROM learning experiences. Its continued availability on abandonware sites and nostalgic retrospectives (like those on YouTube) speaks to a persistent affection for its particular brand of “edutainment.” The fact that Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (via HarperCollins) still owns the IP, as of 2021, ensures these characters and methods remain in the educational ecosystem, even if the medium has changed.

Conclusion: The Last Word in Wordville

Reader Rabbit: Learn to Read with Phonics is more than a sum of its mini-games. It is a testament to a time when educators, artists, and programmers believed that learning to read could and should be a magical adventure. It stands as a pinnacle of the adaptive, phonics-based edutainment model, combining a story with real emotional stakes with a rigorous, multi-modal curriculum scaffolded into a playful world. Its production, however, is inextricably linked to the corporate tailspin that gutted its industry.

Viewed in isolation, it is a 5-star masterpiece of children’s software design. Viewed in history, it is the beautifully crafted final volume of a library whose shelves were about to be catastrophically cleared. It captures the moment before the tsunami—the last, clear, cheerful note before the industry’s cacophony of collapse and the silent dominance of the app store. For that reason alone, Reader Rabbit: Learn to Read with Phonics deserves not just nostalgic fondness, but serious historical recognition as the last great gasp of the CD-ROM learning boom, a game that taught a generation to read just as the world was about to change the meaning of the word “text” forever. Its final, unanswered wish—that the words stay and continue to teach—is one that its players, now adults, are still fulfilling by sharing it with their own children. In that, its story has a far happier ending than Wordville’s.