- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Knowledge Adventure, Inc.

- Developer: Knowledge Adventure, Inc.

- Genre: Educational

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Average Score: 70/100

Description

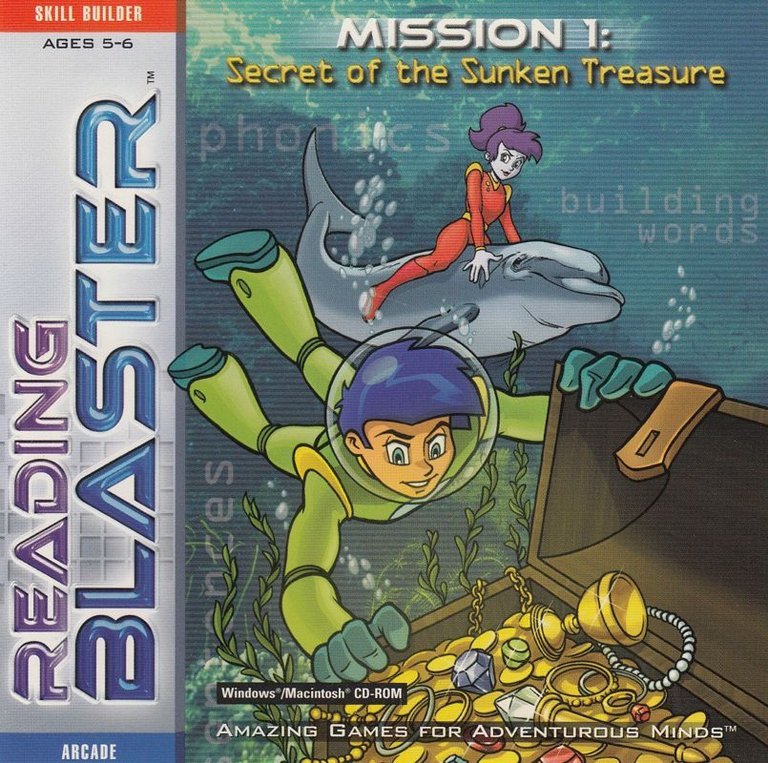

Reading Blaster Mission 1: Secret of the Sunken Treasure is an educational computer game designed for children aged five to six, set in an engaging underwater world where players join Blaster and G.C. to practice reading and problem-solving skills through activities like seahorse racing and sand dollar matching. The game covers essential learning topics including phonics, rhyming words, spelling, letter recognition, alphabetical order, opposites, categorizing, and sentences, with over 450 vocabulary words integrated into its gameplay.

Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (70/100): Average score: 70%

Reading Blaster Mission 1: Secret of the Sunken Treasure: Review

Introduction

In the pantheon of educational software, few franchises hold as much nostalgic weight as the Blaster series. Born from the fertile ground of Knowledge Adventure in the 1990s, these titles sought to transform the often-dreaded drudgery of homework into captivating, interactive adventures. Among its many iterations, Reading Blaster Mission 1: Secret of the Sunken Treasure stands as a specific, targeted entry, designed to guide the youngest of learners—ages five to six—through the foundational principles of literacy. Arriving in 2001, the game promised a subterranean voyage of discovery, blending phonics, spelling, and vocabulary with an underwater treasure hunt. However, as we will explore, its execution presents a fascinating case study in the efficacy and limitations of educational game design. This review will argue that while Reading Blaster Mission 1 is a competent and well-organized product that successfully achieves its pedagogical goals, it ultimately suffers from a “cookie-cutter, ho-hum feel” that prevents it from transcending its genre and becoming a truly memorable experience. It is a functional tool for learning, but not an inspiring vessel for imagination.

Development History & Context

To fully appreciate Reading Blaster Mission 1, one must understand its creator and the era in which it was forged. The game was developed and published by Knowledge Adventure, Inc., a titan of the educational software market throughout the 1990s. Founded by educational experts and software engineers, Knowledge Adventure built its reputation on a simple, yet powerful premise: make learning fun. They were masters of edutainment, a genre that reached its zenith in the mid-to-late 90s with titles like Math Blaster, JumpStart Adventures, and Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego?

The Blaster series itself was a flagship franchise, with its own distinct identity. Unlike the more open-world JumpStart series or the mystery-solving Carmen Sandiego brand, Blaster games were typically built around a central thematic concept—space for Math Blaster, and now, the ocean for Reading Blaster Mission 1. This allowed for a consistent visual and narrative framework that could be adapted to various academic subjects. The technological constraints of the era were significant yet formative. Released in 2001 for Windows and Macintosh on CD-ROM, the game was a product of its time, featuring pre-rendered 3D graphics and simple point-and-click interfaces. The hardware limitations necessitated a reliance on reusable character models, static backgrounds, and compressed audio files, which would heavily influence the game’s visual and auditory identity.

The educational landscape of the late 1990s and early 2000s was also a key factor. There was a burgeoning market for PC-based learning tools as home computer ownership became widespread. Parents and educators were actively seeking software that could supplement early education in an engaging way. This created a fertile environment for Reading Blaster Mission 1, which positioned itself as a direct solution for teaching kindergartners and first-graders essential pre- and early-reading skills. The game was part of a deliberate and calculated product plan, bridging the gap between earlier titles like Reading Blaster: Ages 6-8 (1998) and the subsequent release of Reading Blaster Mission 2: Planet of the Lost Things (2001), demonstrating Knowledge Adventure’s strategy of creating a cohesive, age-graded series to capture a young audience from their first steps in education through their elementary years.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The narrative of Reading Blaster Mission 1 is a classic example of a “thinly veiled premise,” a structure where the plot exists primarily as a vehicle for the educational content. The game opens by introducing its central characters, Blaster and G.C., who are dispatched on an underwater mission. Their objective is to hunt for a sunken treasure, a goal that serves as the narrative glue holding the disparate learning activities together. The plot is functional rather than complex, featuring no antagonists, no rising action, and no real climax beyond the collection of the final piece of treasure. This narrative simplicity is by design, ensuring that the young player’s focus remains squarely on the tasks at hand without being distracted by a complicated story.

The characters are equally archetypal. Blaster, the series’ perennial hero, is the player’s avatar and guide, a friendly and encouraging presence. G.C. (presumably Galactic Commander) acts as the mission’s dispatcher, providing instructions and context from a hub or “Command Center.” Their dialogue is purely transactional, designed to deliver instructions, offer praise, and motivate the player. There are no character arcs, no personality quirks beyond their defined roles, and no memorable lines. The game excels at creating a safe and supportive space; the tone is consistently upbeat and positive, with an emphasis on encouragement over criticism. The lack of a complex narrative is not a flaw in the context of its educational mission, but it does highlight the fundamental difference between a narrative-driven game and a curriculum-driven one.

The primary theme, therefore, is not adventure or mystery, but accomplishment. The entire game is structured around a series of small, manageable victories. Each successfully completed mini-game is a step closer to the ultimate goal of finding the treasure. This creates a powerful positive feedback loop, linking the cognitive act of learning (e.g., identifying a rhyming word) with the emotional reward of progress (e.g., earning a seashell to unlock a race). The underwater setting itself is a thematic choice, meant to evoke a sense of exploration and wonder. However, the narrative fails to lean into this potential. The world feels like a simple backdrop—a collection of themed rooms—rather than a living, breathing environment with its own rules and lore. The treasure is never explained, its history is unknown, and its discovery holds no emotional weight beyond the game’s programmed fanfare. The story is, in essence, a skeleton; it provides a structure but lacks the flesh and muscle that would make it come alive for a young player.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The core gameplay loop of Reading Blaster Mission 1 is a hub-and-spoke model, a common and effective design for educational software. From a central underwater hub (likely the aforementioned Command Center or a main grotto), the player can choose from a variety of “seahorse racing to sand dollar matching” activities. This choice is a key element of the design, giving the player a sense of agency and allowing them to select activities that either appeal to them most or target specific skills they wish to practice. This structure ensures that the experience remains flexible and non-linear, crucial for holding the attention of a young child.

The mini-games themselves are the heart of the game, each one a finely tuned exercise in a specific educational topic. The provided source material lists a comprehensive curriculum: phonics, rhyming words and pictures, spelling, upper and lowercase letters, alphabetical order, opposites, categorizing, and sentences, with a library of over 450 vocabulary words. For instance, a “seahorse racing” game might involve correctly identifying words with a specific phonetic sound to speed up the seahorse, while a “sand dollar matching” activity could be a simple card-matching game where the player pairs words with corresponding pictures. This variety is one of the game’s greatest strengths, as it prevents the repetition from setting in that can plague so many drill-and-practice exercises.

The game’s UI is designed with its target audience in mind. It is large, colorful, and uncluttered, with clear icons and easily selectable options. Instructions are given verbally and visually, making it accessible to pre-readers. Input is limited to the keyboard and mouse, the standard peripherals of the era, and the interface is responsive, providing immediate feedback to the player’s actions. A key system, likely involving the collection of items like shells or stars, acts as a form of meta-progression, unlocking new activities or areas of the hub as the player completes challenges. This provides a tangible sense of advancement that motivates continued play.

However, the system is not without its flaws. The SuperKids review’s description of a “cookie-cutter, ho-hum feel” extends directly to the gameplay mechanics. While each mini-game teaches a different skill, the underlying interaction is often remarkably similar: click on the correct answer, watch a small animation, and receive a reward. This lack of mechanical diversity can lead to a sense of monotony. The games may be educational, but they rarely feel like games in the sense of offering dynamic challenge or emergent gameplay. The absence of a difficulty curve is also a notable limitation; the activities are static, potentially becoming too easy for a quick learner or too difficult for one who is struggling, with no in-system adaptation to the child’s performance.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The underwater world of Reading Blaster Mission 1 is a prime example of late-90s/early-2000s educational art direction. It is a cheerful, sanitized, and brightly colored version of the ocean floor, far removed from the potential darkness and mystery of the deep sea. The aesthetic is cartoonish and exaggerated, with oversized seashells, friendly-looking fish, and vibrant, saturated colors. The overall impression is one of safety and accessibility, deliberately designed to be non-threatening and engaging for a five or six-year-old. The perspective is described as “3rd-person (Other),” which likely refers to a static, isometric, or slightly angled view common for point-and-click adventures of the time, allowing the player to see their character and the immediate environment without the complexity of a full 3D world to navigate.

The art assets are a mix of pre-rendered 3D models for characters like Blaster and 2D backgrounds and sprites for the environment. While this approach allowed for a certain level of character animation, the reuse of models and the static nature of the backgrounds give the world a somewhat artificial, staged feel. The locales—the hub, the race track, the sandy matching areas—are distinct thematically but lack a cohesive sense of place. They feel like levels in a theme park rather than interconnected parts of a living ecosystem. Nevertheless, the art is functional and clear. The educational elements are presented with high contrast and large, legible fonts, ensuring that the focus remains on the learning objectives.

Sound design in educational games is paramount, and Reading Blaster Mission 1 leans heavily on its audio cues. The soundscape is a cacophony of cheerful beeps, bloops, and jingles that play in response to every action. A correct answer is met with an upbeat, positive sound effect, while an incorrect one might trigger a gentler, “try again” tone. This constant auditory feedback is crucial for keeping a young player engaged and informed of their progress. Voice acting is used for character dialogue and instructions, providing a personal and clear line of communication. The music is similarly upbeat and low-key, designed to create a pleasant atmosphere without being distracting. It is the aural equivalent of the visual style: consistently positive and functional. The sound design succeeds in its goal of creating a supportive, encouraging audio environment, but like the art and gameplay, it lacks a unique identity, blending into the general soundscape of other children’s software of the era.

Reception & Legacy

At launch, Reading Blaster Mission 1 received a modest reception, with its legacy preserved primarily through historical archives rather than widespread contemporary acclaim. According to MobyGames, its critical score was 70%, based on a single review from SuperKids. This lukewarm assessment is telling, as the review praised the game for being “well-organized, and attractive” while simultaneously damning it with faint criticism, calling it “cookie-cutter” and possessing a “ho-hum feel.” This perfectly encapsulates the game’s position in the market: it was a solid, professional product, but not one that broke new ground or inspired Passionate devotion.

Player feedback, based on the two ratings on MobyGames, is surprisingly more positive, averaging a perfect 5 out of 5. However, it is crucial to contextualize this. With zero written reviews, these ratings likely come from individuals with a strong nostalgic connection to the game, perhaps parents or now-grown adults who used it as children. This emotional bias is common with titles from one’s youth and may not reflect an objective assessment of the game’s quality or innovation.

The game’s legacy is one of quiet competence rather than industry influence. It represents a high-water mark for functional educational software. It successfully achieved its goal of teaching its target curriculum in an engaging, if not thrilling, way. It is a testament to the robust design principles of Knowledge Adventure, who could reliably produce a polished and effective learning tool. However, it did not push the boundaries of the medium. Its influence is subtle, seen in the countless other educational games that have since adopted its hub-and-spoke structure and its reliance on mini-games for discrete skill-building. The game was a cog in the vast machine of 90s edutainment, an important and well-built cog, but ultimately just one of many. Its place in history is as a representative example of the era’s educational game design, a snapshot of how technology was being used to teach children to read before the advent of more sophisticated and integrated platforms like tablet-based learning apps.

Conclusion

Verdict: A Functional, but Ultimately Forgettable, Subterranean Study Session

Reading Blaster Mission 1: Secret of the Sunken Treasure is a product of its time and its genre, a title that executes its specific mandate with precision but without inspiration. It is the very definition of a “solid B-grade” educational game. As a tool for learning, it succeeds admirably. Its curriculum is comprehensive, its activities are varied, and its presentation is clear, supportive, and age-appropriate. For a five or six-year-old in 2001, this game would have been an effective and engaging way to practice phonics, spelling, and vocabulary.

However, when viewed through the lens of video game history, its flaws become more apparent. The narrative is a perfunctory frame, the gameplay is repetitive, and the world-building lacks depth. Its “cookie-cutter” nature, as aptly described by its lone critic, prevents it from rising above the noise of its contemporaries. It is a game you use, not one you play for the love of the experience itself.

Ultimately, Reading Blaster Mission 1 deserves to be remembered not as a classic, but as a competent and historically significant artifact. It represents the pinnacle of a specific design philosophy for educational software—one that prioritized curriculum delivery over creative expression. It is a valuable time capsule of an era when a CD-ROM could hold a child’s attention and teach them to read, all through the simple power of a cheerful alien and a sunken chest of phonics. For historians of gaming and education, it is a fascinating case study. For everyone else, it is a nostalgic footnote, a reminder of a time when learning and computing were first beginning to merge in our homes.