- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Educational Simulations, Inc.

- Developer: Educational Simulations, Inc.

- Genre: Educational, Geography, History, Role-playing (RPG), Simulation, Sociology

- Perspective: Text-based

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Character attributes, Dating, Decision making, Having children, Life simulation, Moral choices, Random events, Romance

- Setting: Global, Real-world

- Average Score: 72/100

Description

Real Lives is an educational simulation game released in 2002 that allows players to experience life from the perspective of a person born in any country around the world. Starting with randomly assigned attributes such as gender, name, family, and socioeconomic background—or customizing them via a character designer—players navigate life through text-based scenarios, making choices in education, career, relationships, and moral dilemmas. Time advances in yearly intervals, during which dynamic events like illness, disasters, job promotions, or family changes occur. With 62 possible event types affecting attributes like Intelligence, Happiness, Wisdom, and Conscience, the game simulates real-world sociological, economic, and cultural conditions, offering unique, thought-provoking perspectives on global life experiences in a simple, interface-driven format.

Where to Buy Real Lives

PC

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

en.wikipedia.org : “everyone should play it at least once in their own lives.”

mobygames.com (90/100): An original, engaging game that’s fun to play, education be damned.

Real Lives: Review

Introduction: The Game That Made You See the World from 190 Different Angles

In the decades since their invention, video games have often leaned on escapism – transporting players to battle-torn galaxies, pixelated cities under siege, or palette-swapped retro worlds where a mushroom can make you grow uncontrollably large. But what if a game had no bosses to fight, no swords to swing, no objectives beyond surviving each “Age A Year” button press? What if, instead, it asked you to inhabit the life of a child born in a remote village, a student in a crowded city, or a farmer under economic collapse – not to “win,” but to witness? This is the radical, underappreciated premise of Real Lives, a 2001 life simulation game developed by Educational Simulations (later Neeti Solutions), and it is one of the most quietly revolutionary edutainment titles in gaming history.

Real Lives doesn’t just aim to teach social studies; it is an interactive sociology dissertation. It forces players to confront the harsh realities, quiet triumphs, and intricate socio-political variables of existence in 190 different countries – from the relative ease of life in Canada to the crushing burdens of disease, war, and poverty in Afghanistan or the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The game doesn’t simulate combat, puzzles, or objectives – it simulates life itself, with all its randomness, cruelty, tragedy, and beauty.

My thesis is this: While dismissed by some as a “text-heavy edutainment romp,” Real Lives is, in fact, a profoundly humanistic, structurally bold, and morally resonant piece of interactive art that anticipated the “procedural storytelling” and “empathy-building” debates that would dominate game criticism two decades later. It leverages data about real-world geography, health, economy, education, and gender to craft experiences that are not only playable social studies courses, but cautionary tales of privilege, systemic inequality, and the fragility of existence. What separates it from titles like The Sims or Beach Life is its total embrace of realism without fantasy – lives can end at four due to malnutrition, parents can beat children with numerical consequences, and a rockslides in Indonesia have the same mechanical weight as a job loss in Minneapolis. This is a game that invites players to see their own lives mirrored across continents – or to experience the world through a lens of profound difference.

Real Lives was never meant for commercial stardom. It’s a niche product, a labor of educational passion, and a philosophical statement wrapped in a turn-based life sim. But as our world grows increasingly globalized and interconnected, games like Real Lives offer something indispensable: a mirror held up to the lived experiences of billions of people we might otherwise never understand. It’s time we recognized it for what it truly is – not just a curiosity, but a landmark title in the history of humanitarian video games, simulation design, and narrative experimentation.

Development History & Context: An Educationalist’s Labor in a Polished-Platformer Era

To understand Real Lives, one must first grasp the elemental mismatch between its developer’s ethos and the gaming ecosystem of the early 2000s. The game was developed by Educational Simulations, Inc., a small, privately funded studio (later acquired and operated by Neeti Solutions in Pune, India) whose mission statement was not “entertainment” but analytics, empathy-building, and cross-cultural understanding. While companies like Maxis were releasing The Sims (2000), a game that simulated urban life with a glittering cartoonish veneer and microtransaction-ready object placement, Real Lives was being coded to align with UNICEF health data, World Bank economic reports, and World Health Organization demographics. It was born, not from a desire to visualize suburban whimsy, but to visualize disparity.

The Vision: Data-Driven Witnessing, Not Power Fantasy

The creators’ vision was audacious: to create a game so grounded in real statistical probability that playing it over multiple lives would force players to internalize the massive differences in opportunity, health, and mortality rates between the Global North and South. The core design loop – being randomly assigned a life in a country, then reacting to statistically accurate events – was a method of forced perspective-taking. There are no RPG classes, no leveling up to attain power over the world – only choices that carry real consequences based on your locality, gender, and attribute profile. This is simulation as anti-fantasy – an attempt to remove the magical scaffolding that most games use to insulate players from real-world helplessness.

The developers sourced their considerable database of 190 countries, building algorithms that:

– Pull realistic name databases (e.g., Indian/Santali female or male first names, last names, regional names based on rural/urban)

– Simulate realistic upbringing (diet based on national nutrition stats, disease prevalence from WHO).

– Model economic/political context: school access varies by gender and country, income correlates with real GDP per capita, and career advancement is rarely guaranteed for many.

– Generate domestic, societal, geopolitical crises: birth injuries, maternal mortality, earthquakes, floods, war, disease outbreaks, riots, corruption, famine, and even natural phenomena like asteroid impacts. The game claims 62 different event types.

– Allow Google Maps integration (in later editions) to pin down your character’s actual birthplace.

The Technological Constraints: Simplicity as a Feature, Not a Flaw

Released in 2001 (with a Windows build finalized in September 2002), the game was designed for an era dominated by MMOs, fast-paced shooters, and graphically intensive simulation titles like The Sims or SimCity 4. Consequently, Real Lives had to be lean. It’s built like a spreadsheet, optimized for fast calculations, as easy to parse as a PowerPoint presentation. The UI is divided into columns: your 12 attributes, a map of the world, a life log, character status, decision/event windows, arranged in windows you can toggle or hide.

This “Office program” aesthetic – flat, form-based, minimalist – was widely mocked in early reviews, but it is a deliberate design choice. It reinforces the game’s educational mandate: this isn’t “fun and flashy,” it’s serious. The absence of sound, music, and vibrant graphics forces the player to engage solely with narrative, statistics, and moral dilemmas. The game is lightning-fast, designed for classroom play sessions of 60-90 minutes – a life from cradle to grave. It was never meant to compete with StarCraft for multihour binges.

The Gaming Landscape & Its Lack of Empathy Games

The early 2000s commercial market was dominated by power fantasies: war sims (Call of Duty, Brothers in Arms), sports dominance (NBA 2K), or control-based mayhem (GTA III). Titles like The Sims offered domestic control – you built houses, managed moods, cared for pets, but rarely faced consequences like famine, disease, or war. There was no mainstream game that ready readers educate players on systemic inequality, or made them feel the weight of a real-life death (not an avatar’s fake “game over” state).

Real Lives was a radical departure. It offered no power fantasy. In fact, it’s more likely to leave you powerless – your sister dies at birth due to midwife shortage (Sudan, 2021), your child drowns in an unmarked ditch (Brazilian favela), your brother catches AIDS from a hospital blood transfusion (Nigeria, 1989). You are not a hero saving villages from dragons; you are a schoolchild being told her school was shuttered by a week of civil war (Afghanistan). The game was, and is, an empathy machine.

Iterative, Collaborative Evolution

Unlike commercial releases, Real Lives has undergone constant refinement based on user and educator feedback. The wiki notes the 2010 and 2018 revisions, with Neeti Solutions incorporating criticisms, adding Google Maps true-location simulation, 3D character portraits for immersion, and business/entrepreneurship mechanics to model economic agency. This evolution from educator-focused tool to more immersive simulation, while retaining its data foundation, marks a rare instance of a “niche” game iterating gracefully – not chasing trends, but deepening its original intent.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Story of “Life” as a Multi-Trillion Act Play

There is no traditional narrative in Real Lives. No script, no voice actors, no cutscenes. The “story,” in the most literal sense, is the procedurally generated life that unfolds in front of you as you press “Age A Year” and respond to events. But within this emergent logic, lies a deeper, disturbingly resonant set of social, political, and moral themes that are rarely explored in games – and almost never in text-based form.

The Great Absence: Personal Agency in a World of Statistically Programmed Fate

This is a game defined by its lack of control. The game starts in randomization mode: you are a random gender, a random name, born in a random country, with a random income, born into a random caste/class, with randomly assigned base health and aptitude attributes. And from there, random events (floods, war, disease, corruption) will often override any self-driven decisions. You can study, eat well, live modestly, volunteer – and still lose everything in a war you didn’t start, because of a terrorist attack in your district, because of a ban on healthcare access for your gender.

This statistical determinism is the game’s most unsettling narrative device. In a medium defined by player agency, Real Lives radically subverts that: your power is not guaranteed. In fact, in many countries, your fate is already more than half-decided at birth – and the game will tell you with brutal clinicality that “Your mother died during childbirth in mid-woman shortage zone (data: UNICEF, 2000)” or “You contracted polio due to lack of vaccination program (data: WHO, 1998).

Themes: Systemic Inequality, Invisible Privilege, and the CPR of Conscience

– Privilege as Numbers: In India, a girl’s education rate fluctuates wildly. In the U.S., you’re almost guaranteed healthcare, clean water, and digital access. The game doesn’t tell you this – it shows it through mechanics. You can’t “choose” to be poor in the U.S.; the low-income tier is randomized but even the poorest get a base safety net. In Kenya, a random event can grant “Medical insurance funds,” but only 2% of population has data on it. Your “wealth” growth is tied to real national economic indicators.

– The Karma of Choice – Conscience and Wisdom as Status Markers: Unlike attributes on a >RPG status bar, Conscience and Wisdom are deeply narrative. They don’t boost HP. They affect relationship choices, career, and long-term moral path. Save a drowning child? +Conscience. Buy a nice car when your kid is starving? -Conscience. Ignore a corrupt boss or report them? Wisdom determines whether you face legal trouble. This system turns ethics into a game mechanic without being didactic – you learn by doing.

– The Random Engine as Tragic Melody: The RNG dictates a profoundly melancholic rhythm. You invest years in farming, studying, parenting – and then, in the yearly snap, “Your family was killed in bombing.” Oh, God damn it. This isn’t dramatic irony. It’s historical inevitability – the algorithm knows that in Syria, Afghanistan, or D.R. Congo, war frequency and civilian casualty ratios are statistically high. The game isn’t condemning these countries – it’s holding a mirror to geopolitical conflict patterns.

– Gendered Experience and Bipartisan Birth Backdrops: Being born female isn’t just a skin in Real Lives. It affects:

– School access (lower in all Asian and African datasets).

– Marriage (arranged, early, or later, based on trend data).

– Pre-natal care (reduced in low-income countries).

– Domestic violence incidents (which are random events with optional off-switch, because of content sensitivity).

– Choice of career (still biased in STEM fields in global data).

– Opportunity to migrate legally vs. risk of smuggling.

– Even the statistical life expectancy, which is programmatically lower in many countries.

Conversely, male birth = higher likelihood of military conscription, war casualty, alcoholism, and accidents. The game doesn't moralize – it **presents gender as a statistical vector**, not a personal story.

- The “Downer Ending” as Social Commentary: Most games punish failure with “Game Over” screens. Real Lives forces you to confront realistic, unavoidable death: “You have been murdered at age 4.” “You have died trying to save the life of a friend.” “Driven to suicide / terminal cancer / tortured in prison.” These aren’t just diegetic events; they are rare, unnerving pronouncements in a medium trained to offer multiple lives. When you die – and you will, often even after doing “everything right” – there is a moral gravity. You have to start over. But this time, maybe you’re in Canada. Now you feel the difference.

Dialogue: The Text as Interlocutor

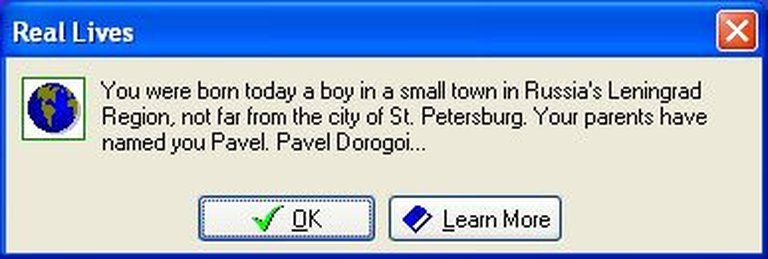

There is no traditional dialogue system. But the game’s text boxes – event descriptions, decision prompts, the “Learn More” informational paragraphs (which appear after each event, citing sources like “Americans watch sports”) – are themselves a form of narrative. The “Learn More” feature is critical: it transforms every tragedy (e.g., “Your son drowned in a well lacking safety fencing”) into an opportunity to read a 2-3 sentence microlesson on, say, water infrastructure, child labor, or rural poverty. This mechanic is uniquely educational, turning every event into a teachable moment without breaking immersion.

The frequent statistical asides (“In this country, 68% of female children complete primary school”) are embedded within the event screen, creating a textual world where facts and feeling coexist. This is the game’s greatest trick: it’s a life sim and a textbook, folded into one.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Deconstruction of “Life Turns” and Emotional Calculus

The gameplay of Real Lives is defined by one central mechanic: the annual “life turn.” Every time you press “Age A Year,” the game calculates a cascade of effects – random events, attribute adjustments, family changes, career progress, relationship evolution, and new available decisions. It’s a simulation engine wrapped in a turn-based RPG interface, where the “action” is thought, choice, and outcome.

Core Systems and Their Interplay

1. The Turn-Based Lifecycle:

– 0-7: Finite choices. Parents control nutrition, healthcare, basic leisure (toys, stories).

– 8-12: Lives open. Choose leisure activities (sports, drawing, music, swimming, reading) → these boost base attributes (Athletic, Artistic, Musical, etc.).

– 13-17: Romance system. You can date, and later, enter relationships. At 16+, same-sex attraction may be triggered (see below). From 17+, choices affect future career.

– 18+: Autonomy day. Move out, go to college, get a job, marry, start a business (2010+ editions), have children.

– Every age: moral decision prompts. Drunk man on street? Choose. Peer pressure to cheat? Choose. Political protest participation? Choose. These decisions affect Conscience/Wisdom, which in turn affect attraction, scholarships, promotions.

-

The Attribute System: Inherited vs. Learned:

- Inherited (7 attributes): Intelligence, Artistic, Musical, Athletic, Strength, Endurance, Appearance. These are largely fixed at birth, with minor fluctuations from activity choices. They affect everything – from dating pool to job type to success rates (higher Int = faster college graduation).

-

Learned (3 key attributes): Happiness, Conscience, Wisdom. These are dynamic – fluctuating based on decisions, events, relationships, wealth, health.

- Happiness: Real-time status. Affected by diet, income, family health, consumer spending, housing stability (depression risk: low income + no family = -2pts).

- Conscience: Moral meter. High conscience = better job offers (nongovernmental orgs), deeper relationship, but may lead to lower income (rejecting bribery).

- Wisdom: Prudence level. Affects financial decisions, long-term planning, crisis management. High wisdom = better long-term savings, fewer debt-induced tragedy.

-

Note: Conscience and Wisdom are not cosmic moral meters – they’re tied to real-world outcomes. You don’t “level up” to be “good.” You make repeated choices, and the game tracks them. This is closer to a behavioral psychology simulation than a D&D alignment system.

-

Random Event Engine: The 62 Degrees of Tragedy/Opportunity

-

This database is the game’s genius. Events span from the mundane to the catastrophic:

- Life affirming: “Your child was born healthy,” “You received a scholarship,” “Your business turned a profit.”

- Personal tragedy: “Abusive parents,” “Domestic violence event,” “Driven to suicide,” “Child death,” “Mental illness diagnosis.”

- Societal crisis: “Flood devastated infrastructure,” “Power grid failure,” “Corruption scandal.”

- Geopolitical hell: “War declared,” “Terrorist attack,” “Refugee crisis,” “Religious persecution.”

- Interactive moral dilemmas: “You found a wallet – turn it in?” “Testify against powerful criminal?” “Report child labor?”

-

Crucially, many events are optionally OFFABLE. This is a masterstroke: teachers and players can disable sensitive content (rape, slavery, extreme torture) to make the game suitable for younger audiences. The system respects both realism and emotional safety.

-

-

The “Learn More” Mechanic: Education as Diegetic:

- As mentioned, every event has a “Learn More” button that links to a brief factoid from sources like the World Bank, UNESCO, or state statistics. For example, if you encounter a “no midwife death” event, pressing “Learn More” reveals: “In Country X, the maternal mortality rate is 1 in 22, versus 1 in 5,000 in Country Y. Source: WHO, 2002.” This embeds critical thinking and data literacy directly into the gameplay loop.

-

Family and Relationship Tracking: A Flawed, Emotional Web

- A recurring criticism (from Zack Green, among others) is the inability to track non-cohabiting family. You hear about your sister “having 12 children” in the log, but you can’t see their health, genders, or personalities. The only time you see someone’s attributes is during a romantic interest prompt (“Learn More: Stability: 7/10, Prudance: 9/10, Ambition: 6/10”).

- This is a design trade-off. The game prioritizes simplicity and speed over interpersonal storytelling (unlike FTL’s detailed crew bonds or The Sims’ observable households). The cost is a loss of personal investment in extended family – it’s a network of names on a page, not personalities.

- However, Video Game Caring Potential is strong – Rock, Paper, Shotgun’s team experienced real grief when their “favorite sibling” was lost. This is achieved through repeated mentions, shared childhood memories (“You used to protect her from bullies”), and investment over time – even without visuals.

-

Romance and Children: Mechanical but Sensitive

- Romance is introduced at 13, progresses to relationships at 16+, and marriage at 18+. You’ll swiping-action select partners, each with visible stats (stability, wisdom, ambition, etc.) only if you click “Learn More” when asked.

- Children: Birthed numerically. Their survival depends on poverty level, nutrition, disease prevalence, birth weight. A very powerful comedy trope (cited in TV Tropes) is the “Zero intelligence” baby – a statistic of natural randomness – which feels tragically comic: “My child can’t learn anything, but at least they’re alive.”

-

The Illusion of Freedom vs. Scripted Data

-

You “choose” your career education, but your options are constrained by:

- Country availability (few physicists in Chad, more karma-focused roles like social work).

- Gender (STEM bias in Asia/Africa).

- Wealth (needs-based scholarships).

- Attributes (low Art score won’t let you be a painter).

- Random events (“Drought destroyed cotton crop, so 30% of farmers lost jobs”).

-

This creates a feeling of “determined freedom” – a key innovation. You feel like your choices matter, but they’re never independent of systemic forces. This mirrors real life but is rare in games.

-

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetics of Banality and Truth

Real Lives is intentionally unglamorous. It is not a visual spectacle. Yet its aesthetic – a kind of digital functionalist minimalism – is deeply aligned with its thematic goals.

Visuals: The Vanity Window and the Office-Like Core

The screen is flat, grid-based, and windowed. The only persistent visual element is the map window at the top-center – a color-transformed world map (often styled after Google Maps) – which highlights your country. This is called a “Vanity Window” (per Tropedia) because it can’t be hidden and sometimes blocks action. But it’s also symbolic: the world is always watching, always present.

The rest are data overlays: name, gender, age, 12 attribute bars, current income, family health, life log, event window. No pixel art, no 3D models (until 2010+ updates, which replaced generic squares with 3D human portraits using a simple polygonal figure system, and integrated Google Maps API for real-location birthpanning).

The art style is academic. It’s closer to a PowerPoint slide, a social studies textbook, or a hospital patient sheet. This isn’t an error – it’s a subversion of “game” aesthetics. It says: this is not for escapist entertainment. This is data. This is real. The “Office program” critique (from Morgan Greene and others) is, in this case, valid and purposeful.

Sound: The Silent Mirror

There is no sound, no music, no SFX. This is one of the game’s most commented-on absences. But it’s intentional.

– No music means no emotional alto – no heroic symphony, no sad violin. Every loss feels ten times heavier because it’s silent and internal.

– No SFX removes cheap stimuli. You can’t “feel” a button click or explosion – you have to read it.

– The silence forces self-reflection. You’re not distracted – you’re alone with the weight of the event log.

This is a radical choice for an “entertainment medium” and one of the bravest examples of anti-sensory design – using silence to amplify emotional impact.

Atmosphere: The Aesthetics of Realism

The game’s atmosphere is not “cinematic” or “immersive” in the traditional sense. It’s documentary-like. The “atmosphere” is created by:

– The sheer volume of statistical text

– The frequency of mundane and tragic events

– The absence of narrative closure (no end credits, no “won the life” trophy)

It feels clinical, unbeautiful, and authentic. You don’t “feel” the world – you process it, like reading the news. This is arguably the most real life sim ever made, precisely because it rejects the fantasy of “feeling” in favor of understanding.

Reception & Legacy: The Game That Ordered a Pizza While the World Burned Elsewhere

Critical Reception: A Cult Gem Before Cults Existed

At release, reviews were limited, niche, and polarized (- Metacritic: tbd; MobyGames: 9,083/10,000 from Zack Green’s 2004 review, 1 rating on a 4.5/5 scale).

-

Praise:

- Rock, Paper, Shotgun’s iconic line: “everyone should play it at least once in their own lives.”

- Their editorial team documented a 12-hour group playthrough (9/13/2016) with shaking horror: “Our moment of dread came at 54 when our character’s daughter gave birth to a son in refugee camp, and the midwife died. Then, her husband was drafted into war.” This became a viral moment.

- PopMatters (2004) praised its “social messaging”.

- Zack Green of MobyGames awarded perfect scores in Originality, Emotional Impact, and Story Presentation.

- USA Today (2004) called it “interactive role-playing” that teaches empathy.

- Academic citations: Over 1,000 scholarly references (per MobyGames), in education, sociology, and simulation studies.

-

Criticism (but also validation):

- RPS also criticized the “random number generator brutality – characters as numbers.” This is a backhanded compliment – the game succeeds at making you feel like a statistical outpost.

- Lack of sound or graphics fanciness was a limiting barrier for commercial reach.

- No narrative thread beyond life events.

- UI quirks: family tracking limitations, opaque some attribute progression.

- “Not a game” mentality: some players want escapism, not reality sim.

Commercial Performance & Scholarship

– Shareware model (early editions), then freeware (2004), then commercial (2010+).

– Very few sales data, but high academic penetration.

– Used in high school social studies, college sociology, Peace Corps training, NGO briefings.

– Viral moments: the RPS team saga became a minor meme in game criticism – “a game that broke the journalists.”

Influence and the Industry Shift

Real Lives was a canary in the coalmine, anticipating a genre that didn’t yet exist:

– Procedural Storytelling: Games like FTL: Faster Than Light (2012) and Sunless Sea (2015) adopted similar “random event tables” with novelistic consequences.

– Data Literacy Games: Monaco (2012), Orwell (2016), and Beholder (2016) use data as ethics.

– Humanitarian Games: Never Alone (2014, Alaska Native collaboration), This War of Mine (2014, civilian war sim).

– Empathy-Building: Papers, Please (2013) and Subway Riders (2020) force players to embody workers under moral crunch.

– Simulation as Protest: Alba: A Wildlife Adventure (2020) uses environmentalist narrative, but Real Lives did it first with structural inequality.

Legacy: The Game That Should Be Taught

Today, Real Lives is slowly gaining its due. It’s a lost classic – not just of edutainment, but of game design that dared to be ugly, real, and unbearably honest. It’s available on Internet Archive (DLL files), Neeti Solutions’ site (teacher portal), and Steam (later, 2010+ editions).

A younger generation of designers – those building for climate, migration, or post-capitalism – can learn from it: don’t hide in fantasy. Meet the game in the data.

Conclusion: A Life Sim That Was Never Playing Games with You

Real Lives is not a game in the conventional sense. It doesn’t have a “winning condition.” It doesn’t award gold for saving a princess. It’s not optimizable. It’s not escapist. It’s not fun in the way Fortnite or Skyrim is fun.

But in its relentless, sometimes cruel simulation of real life – in its refusal to offer magical cures to war, or superhero ability to stop disease, or financial windfalls to cover even the most modest life – it achieves something profound and rare in video games: emotional and intellectual gravitas.

It is a marvel of data integration, procedural storytelling, and moral design. It forces players to face the following: Maybe you’re not the hero. Maybe the game isn’t here to reward you. Maybe, just for a moment, you should live as if your world could collapse at any age. And from that existential realism, it doesn’t offer hope – it offers perspective.

The game’s flaws – the flat graphics, the soundlessness, the family tracking limitations – are not accidents. They are design choices that prioritize truth over spectacle, education over excess, mechanism over myth.

In a medium often fixated on power, control, and fantasy, Real Lives stands as a radical act of anti-gaming – a simulation that dares to remind us that most lives on Earth are not “procedural RPGs” built for repeating. They are finite, fragile, and shaped by forces far beyond individual “player” choice.

To play Real Lives once is to experience the world through 190 sets of eyes. To play it twice is to realize you are one of the lucky ones. And that it’s not a game – it’s a mirror.

Final Verdict:

🟥 Not for Eager Power Gamers

🟩 For Players Seeking Truth, Empathy, and Silent Horror of Reality

Real Lives is not just one of the most important educational games ever made. It is one of the most philosophically sound, ethically driven, and narratively revolutionary simulations in video game history. It belongs in the pantheon – alongside Tetris, The Queen’s Gambit, Journey, and This War of Mine – as a game that does more than entertain: it changes how you see the world.

Its 2025 legacy isn’t in reviews – it’s in a thousand school classrooms, a million whispered “holy shit” moments, and one simple, powerful mission: to make you feel, for just a moment, the weight of a life not your own.

And in that moment, against all odds, Real Lives wins.