- Release Year: 2014

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Avanquest Software Publishing Ltd.

- Developer: Fuzzy Bug Interactive

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Hidden object, Mini-games, Puzzle elements

Description

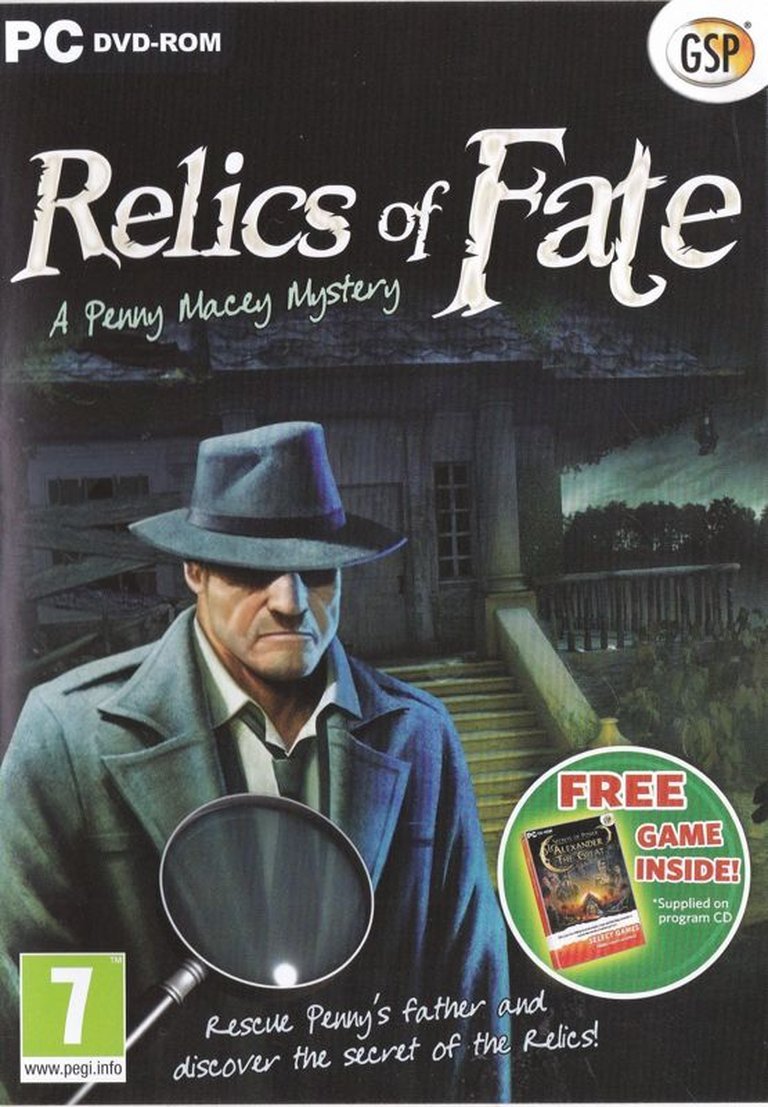

In Relics of Fate: A Penny Macey Mystery, players follow Penny Macey as she investigates the disappearance of her father, private investigator Jack Macey, who was kidnapped while probing a series of robberies connected to ancient relics. This hidden object adventure features point-and-click exploration, puzzle elements, and mini-games across fixed-screen scenes, with two difficulty modes (Casual and Challenge), autosave, and a timer-based scoring system, all presented without voice acting.

Gameplay Videos

Relics of Fate: A Penny Macey Mystery Free Download

Relics of Fate: A Penny Macey Mystery Guides & Walkthroughs

Relics of Fate: A Penny Macey Mystery Reviews & Reception

gamezebo.com : you’ve got a wholly enjoyable game on your hands!

jayisgames.com : which works very well for the type of story being told.

Relics of Fate: A Penny Macey Mystery: A Forensic Case File from the Golden Age of Casual Gaming

Introduction: A Relic Itself in the Hidden Object Genre

In the bustling archives of casual gaming, where titles are churned out with the efficiency of a factory line, Relics of Fate: A Penny Macey Mystery stands not as a towering monument, but as a perfectly preserved, if somewhat unassuming, artifact from a specific and fertile moment in time. Released in 2011 (according to most sources, though MobyGames lists 2014, likely reflecting a re-release or regional publication date), this hidden object puzzle adventure (HOPA) by Fuzzy Bug Interactive and published by Avanquest/Playrix embodies the genre’s mid-2000s to early-2010s sweet spot: mechanically competent, visually pleasant, narratively earnest, and ultimately defined by the conventions it adheres to rather than the boundaries it breaks. This review will argue that while Relics of Fate is not a revolutionary title, its meticulous construction, its unwavering commitment to a specific gameplay loop, and its role as a consummate example of its sub-genre make it an essential study for understanding the “golden age” of the downloadable casual mystery. It is a game that asks not “what if?” but “what next?”—delivering a predictable, satisfying, and ultimately disposable journey that, in its own way, perfected the art of the cozy detective story for a mass audience.

Development History & Context: The Studio, The Publisher, and The Era

The Creators and Their Vision: Fuzzy Bug Interactive, the developer, remains an enigma. With a name suggesting small-scale, perhaps even sole-proprietor, development, they produced a handful of titles in the HOPA space, including Penny Dreadful: Soulless and Mystery Trackers: The Four Aces. Relics of Fate appears to be one of their more ambitious projects, featuring a coherent, multi-chapter narrative and a larger cast of characters than a simple object hunt. The vision was clear: to blend the “crime scene investigation” aesthetic—complete with fingerprint dusting and evidence analysis—with the core hidden object and inventory puzzle mechanics. There is no evidence of a grand design document; instead, the game feels engineered from a checklist of popular genre tropes: a missing relative, a series of collectible MacGuffins (the eight relics), a town full of suspiciously helpful civilians, and a final对峙 in a catacomb.

Technological Constraints and Artistic Compromise: Developed for Windows (and reportedly Mac, though with noted compatibility issues per user comments), the game runs on what was then-standard 2D pre-rendered or simple 3D assets with fixed, flip-screen perspectives—a cost-effective choice that allowed for detailed, painterly backgrounds but limited animation and character expressiveness. The decision to forgo voice acting, noted explicitly in the MobyGames specs, is a stark budget marker. In an era where major casual publishers like Big Fish Games were beginning to invest in full voiceovers for premium titles, Relics of Fate‘s silence places it firmly in the second tier of production values, relying entirely on text boxes and a static musical score to convey mood. The system requirements (CPU: 1.2 GHz, RAM: 512 MB, DX 9.0) are modest even for 2011, targeting the vast market of older home PCs.

The Gaming Landscape of 2011: The early 2010s was the zenith of the “casual” market, particularly the HOPA sub-genre. Steam’s “Casual” category was burgeoning, and portals like Big Fish Games, GameHouse, and Playrix were dominant. The formula was well-established: a point-and-click interface, a series of static scenes filled with hidden objects, inventory-based puzzles, and a light narrative to string it all together. Relics of Fate entered this crowded field with a slight differentiation: a stronger emphasis on “investigation” mechanics (fingerprinting, shoe print analysis, voice-matching) that mimicked police procedurals, aiming to give the player a sense of being a genuine PI. However, as critic JohnB at JayisGames notes, it “ditches the usual string of still scenes packed with items to find and lists to manage in favor of an adventure-style layout,” positioning it as a more adventure-forward HOPA, though it never fully escapes the genre’s core loop.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Mystery Solved by Checklist

The plot of Relics of Fate is a functional scaffolding for its gameplay. Private investigator Jack Macey vanishes while probing a series of thefts linked to eight ancient relics, each associated with a symbol (Salamander, Moon, Snake, etc.). His daughter, Penny, discovers his ransacked office and a mysterious note, thrusting her into the investigation. The narrative unfolds across 12 distinct “Acts,” each corresponding to a location in the town of Newtown and one relic.

Character and Dialogue: Penny is a prototypical silent protagonist. The player sees her only as an icon at the bottom of the screen, her thoughts conveyed through text. This is standard for the genre but creates a disconnect; she performs highly illegal acts (breaking and entering, tampering with evidence, stealing) with the implicit permission of the game’s NPCs, who treat her as an official authority. The supporting cast are thin archetypes: the nervous librarian, the talkative golf pro, the distressed elderly homeowners (Mrs. Miggins, Mrs. Willacre), the suspicious bank manager. Their dialogue is utilitarian, existing solely to provide a task (“Find the key,” “Fix this”) or a weak alibi (“I haven’t seen the relic!”). The thematic exploration of “fate” versus agency is utterly superficial; the relics are plot devices, their “power” never explored beyond being valuable objects.

Plot Structure and Pacing: The story is a picaresque quest. After the initial setup in Jack’s office, Penny receives a map and must visit various locations in any order to retrieve relics. The “mystery” is not a whodunit in the classical sense but a “what’s-in-the-box” scavenger hunt. The true antagonist, the bank manager Mr. Croft (revealed via the butterfly relic ID card), is telegraphed from his first abrasive appearance. The climax at Miller’s Mansion and the subsequent catacomb sequence is a final gauntlet of puzzles, not a revelation. The ending, where Penny rescues her father and the culprit is presumably arrested off-screen, is an anticlimax. The narrative’s primary function is to provide geographical and logical justification for moving from one hidden object scene to the next. As the Gamezebo review astutely observes, the story makes “Penny fairly difficult to like” due to her blasé disregard for law and privacy, a moral vacuum that highlights the genre’s often-tenuous relationship with realism.

Thematic Superficiality: The game gestures at themes of family legacy (the “Macey” name), the weight of history (the ancient relics, the catacombs), and civic duty, but never develops them. The catacomb, presented as a grand discovery, serves only as a final puzzle hallway. The relics themselves, despite names like “Lotus” and “Butterfly,” have no intrinsic meaning. The theme of “fate” is limited to the title and the contrived coincidence that all relics are in Newtown. It’s a plot soup made from stock ingredients, designed to be consumed quickly and forgotten immediately.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Relentless Grind of the Hunt

Relics of Fate is a game defined by its systems, which are both its greatest strength and its eventual weakness through repetition.

Core Loop and Scene Structure: The gameplay alternates between three modes:

1. Exploration Scenes: Static screens where the player hunts for interactive hotspots (sparkles) and inventory items. These are the “adventure” segments.

2. Hidden Object Scenes (HOS): Dedicated screens filled with clutter, requiring the player to find a list of items (often multiple instances, e.g., 10 coins, 6 stamps). Critically, as the Moby description states, “items are hidden in plain sight, nothing has to be moved or combined to reveal an object.” This is a key design choice—objects are simply camouflaged into the background, requiring keen observation but no environmental manipulation.

3. Mini-Games and Puzzles: A variety of logic and dexterity challenges that gate progress. These are the game’s most memorable and varied elements.

The “Key Object” and Container System: A central mechanic, praised by JayisGames, is the “container items” system. When the player needs to perform an action (e.g., open a drawer, repair a cage), a large magnifying glass appears with silhouettes of required items. The player must find those items in the current scene and place them into the circle. This elegantly integrates inventory management with environmental puzzles, creating a clear “what do I need?” feedback loop and reducing aimless clicking.

Inventory and Progression: Inventory items are collected and used in subsequent scenes, often in a linear chain. There is no crafting in the modern sense; combination is always dictated by the “Key Object” prompts. Progression is strictly linear within a location but non-linear on the macro scale via the map introduced after the library chapter. The player can choose the order of relic locations, but each location’s internal progression is a fixed sequence of tasks ending in a relic retrieval and a return to the office “Intermission.”

Puzzle Variety and Design: The mini-games are the game’s crown jewels, showcasing considerable variety:

* Jigsaw Puzzles: Simple shape-sorting, like the map reconstruction after the library fire.

* Word Search: A basic linear search in the library back room.

* Logic/Rotation Puzzles: The “animal key” sequence box (ordering animals based on clues), the Mayan circle puzzle (rotating rings to form an image), and the pipe-matching puzzles (rotating pipes to create a flow). These are often poorly explained, requiring trial-and-error, as noted in both the walkthroughs and the Gamezebo review (“give you no explanation whatsoever”).

* Pattern Matching: The golf ball color/number puzzle and the circuit board hex-grid puzzle.

* Dexterity/Reaction: The bell cord key-fishing mini-game (timing-based) and the “clean the oil” brush-minigame (clicking until a meter fills).

* Code-Based: The combination lock on the golf cart safe and the final Mayan tile alignment puzzle.

The quality of these puzzles is uneven. The logic puzzles are satisfying but opaque. The dexterity tasks are simple filler. The final tile puzzle is notorious among players for potential randomization bugs, as one Game Giveaway commenter laments: “the final tile problem does not have the right tiles… It seems there was a random generation instead of the ones that should have been included.” This speaks to a development priority on puzzle variety over rigorous playtesting for solvability.

Difficulty and Modes: Two modes exist: Casual (more hints, no click penalty) and Challenge (fewer hints, penalties for rapid clicking on empty areas). However, the hint system is tied to the dog Hamish, who “sleeps” after use. As one user comment clarifies, this is a standard recharge timer, but its presentation is “horribly twee.” The game’s biggest flaw, repeatedly cited in user reviews, is the saving system. Autosave occurs only at the beginning of a new scene/act. Quitting mid-scene forces a full restart of that scene’s hidden object and puzzle sequence. This “old school” penalty, noted by multiple commenters on JayisGames and Game Giveaway of the Day, is a significant frustration in an era of player-friendly saves and is a primary reason many users abandoned the game.

Interface and UI: The point-and-click interface is responsive. The “sparkles” for hotspots are clear. The inventory is always visible. The primary UI flaw is the lack of a persistent task list in Challenge Mode, forcing players to remember objectives, which can lead to backtracking confusion.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Competent But Unmemorable Facade

Visual Style and Atmosphere: The game employs a fixed-perspective, pre-rendered 3D aesthetic common to the era. The art is competent but inconsistent. Background scenes—the library, the golf course, the derelict house—are often well-drawn with a pleasant, saturated color palette and a convincing sense of place. However, character animations (like Penny’s icon, the librarian, the clerk) are simplistic, sometimes muddy, and lack the polish of top-tier contemporaries. The environments serve their purpose: they feel like real, if exaggeratedly cluttered, locations where one could find a “dustpan” or a “green tee with two lines.” The atmosphere is neutral to slightly eerie in the catacomb sequences but generally leans toward cozy mystery. It lacks the gothic grandeur of a Mystery Case Files title or the crisp realism of a Seekers game, settling into a safe, middle-ground visual identity.

Sound Design: The soundscape is minimal. There is no voice acting—a major omission for narrative immersion. The sound effects are functional: clicks, item pick-ups, the clink of coins. The musical score is a single, looping, mildly mysterious track per location, pleasant enough to fade into the background but never memorable. The silence where dialogue should be is the most glaring audio flaw, making conversations feel static and reducing character presence. The only audio character is Hamish’s occasional bark, which one user noted “still makes barking noises even when the SFX volume is all the way down,” a minor but telling bug.

Contribution to Experience: The art and sound create a consistent, if bland, aesthetic. They successfully differentiate locations (the warm wood of the library vs. the cold tiles of the bank manager’s office vs. the earthy catacombs) but do not tell a story beyond the immediate gameplay need. The world feels like a series of dioramas, which is exactly what it is. This visually reinforces the gameplay’s “checklist” nature; Newtown is not a living town but a collection of test environments.

Reception & Legacy: The Middle Child of Casual Gaming

Critical and Commercial Reception at Launch: Relics of Fate existed in the crowded middle of the casual HOPA pack. It was not a breakout hit like Gardenscapes or a critical darling like the early Mystery Case Files. Its reception was lukewarm to positive among its target audience. The Gamezebo score of 60/100 succinctly captures the consensus: “if you can let yourself become accustomed to Penny’s way of doing things… the gameplay here is fairly solid, if a bit repetitive.” The review praises the visual design (“livened up with a number of animated characters and items, all presented in smooth, shaded 3D”) but criticizes theStory as weak and Penny’s morality as problematic.

User reviews from the time (archived on JayisGames and Game Giveaway) reveal a dedicated but occasionally frustrated player base. Common praises: enjoyable puzzle variety, good length (4-10 hours), and satisfying completion. Common complaints: the punishing save system, the overly simplistic or obscure puzzles, the lack of voice acting, and the repetitive nature of finding “10 coins” for the fifth time. One user, “StealthBunny,” detailed the workaround for the black-screen launch issue on Windows XP, indicating a lack of optimization. Another, “IngeZ,” highlighted a localization flaw where a single word (“stamps”) referred to two different objects (postage stamps and office stamps), making translated versions frustratingly ambiguous—a subtle but significant design oversight.

Evolution of Reputation: Over time, Relics of Fate has not undergone a critical reappraisal. It remains a footnote, known primarily to HOPA completionists and those who played it during its initial run on Big Fish Games (now delisted, though walkthroughs persist). Its reputation is that of a solid, mid-tier entry—a game that does everything it sets out to do adequately but lacks the spark to be remembered. It is often used as a benchmark for “standard” HOPA design in the early 2010s.

Influence on the Industry: Its direct influence is negligible. It did not pioneer mechanics; it implemented existing ones (the container system from Treasure Seekers, the map-based non-linear progression). However, as part of the collective output of studios like Playrix and Big Fish Games, it represents the commodification and standardization of the HOPA genre. It demonstrates the formula’s durability: a mystery plot, a list of locations, hidden object scenes interlaced with puzzles, and a final collect-’em-all climax. Later, more ambitious titles (Criminal Case, Hidden Expedition) would build on this foundation by adding more narrative choice, 3D environments, and social features, but Relics of Fate is a pure, uncut example of the template.

Conclusion: A Time Capsule of Calm, Calculated Design

Relics of Fate: A Penny Macey Mystery is not a forgotten masterpiece. It is a competent, workmanlike, and ultimately ephemeral product of its time. Its strengths lie in its mechanical clarity and its respectable array of puzzle types, which provide a steady stream of cognitive engagement. Its weaknesses are the systemic flaws of its genre and era: a morally vacuous narrative, punishing save mechanics, and a visual-auditory design that prioritizes function over flair.

Definitive Verdict: In the canon of video game history, Relics of Fate does not occupy a hallowed hall. Instead, it belongs in a vitrine labeled “The Peak of the Standardized Casual Mystery, c. 2008-2013.” It is an exemplary case study in how to build a reliable, enjoyable, and completely disposable experience from a well-worn blueprint. For the game historian, it is invaluable as a baseline—the game you play to understand what the average, non-innovative HOPA was like at its most popular. For the contemporary player, it offers a pleasant but unremarkable few hours, a nostalgic return to a simpler, quieter, and more repetitive corner of gaming where the greatest mystery was not “whodunit” but “what’s the next thing I need to click on?” It succeeds entirely on its own limited terms, and in doing so, perfectly captures the comforting, predictable, and ultimately forgettable charm of its genre’s golden age.