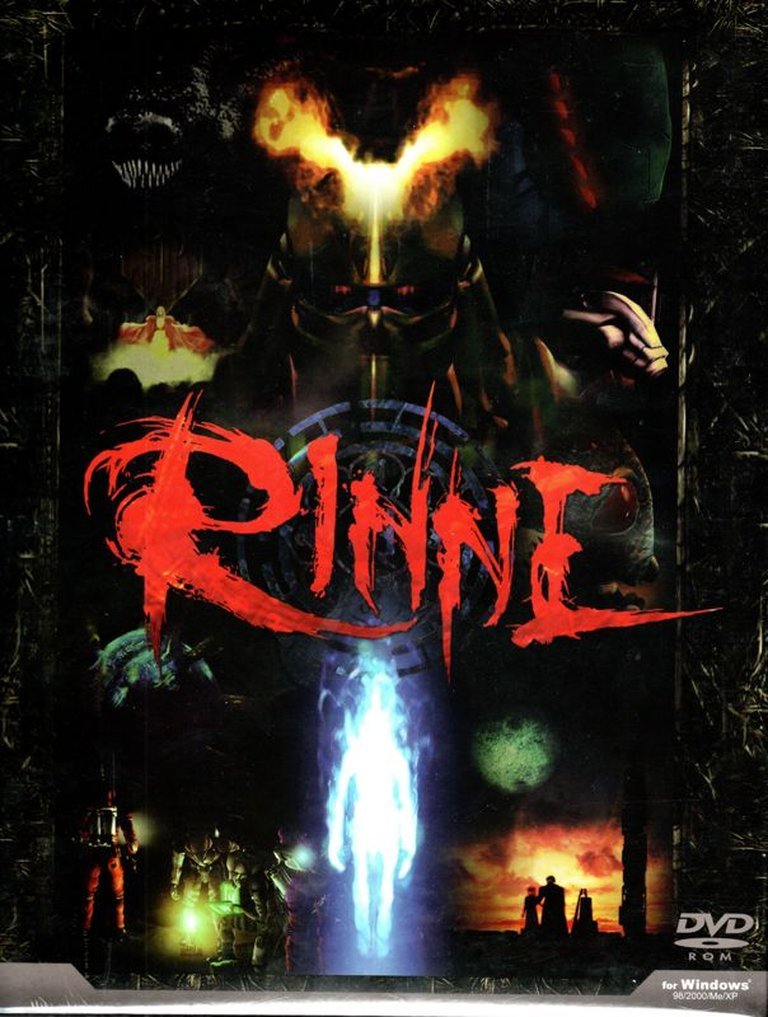

- Release Year: 2005

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Softbank Corp.

- Developer: Bothtec, Inc., Nihon Falcom Corp.

- Genre: RPG

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Action RPG, Branching story, Possession, Puzzles, Summoning, Transformation, Traps

- Setting: Fantasy, Futuristic, Sci-fi

Description

Rinne is an isometric action role-playing game set in a distant future where humanity has abandoned Earth for a planet engulfed in a historic war between the HEAVEN and HELL factions. Players assume the role of the Valkyrie, an avatar deployed by MARX colonists into a virtual recreation of this world, relying on unique Body Snatch and Transform abilities to possess enemies, gain their skills, and progress without experience points, while navigating real-time combat, puzzles, traps, and branching story paths that culminate in multiple endings, all under the pressure of a 60-second timer to find a new host if the current one is killed.

Rinne Reviews & Reception

hardcoregaming101.net : Everything feels like a placeholder for a beta version of the game, rather than something from a finished product.

cohost.quiteajolt.com : It’s quite nice, actually!

Rinne: Review – A Phantom Relic from Falcom’s Forgotten Frontier

Introduction: The Ghost in the Machine

In the vast museum of video game history, most titles are catalogued with clear provenance: a celebrated studio, a marketing campaign, a cultural footprint. Then there is Rinne—a game that feels less like a released product and more like a stray data packet recovered from a corrupted hard drive. Released for Windows in Japan on June 30, 2005, by publisher Softbank Corp. and developed in a shadowy collaboration between the legendary Nihon Falcom and the then-doomed Bothtec, Rinne exists in a state of perpetual contradiction. It is a sequel to the obscure Relics series yet bears no series title; it is a Falcom game yet lacks their signature polish and credit rolls; it presents a conceptually rich, mechanically deep action-RPG yet is assembled from the visual detritus of a cancelled Xbox project and repurposed audio prototypes. This review argues that Rinne is not merely a failed game, but a profound historical artifact—a poignant, messy, and brutally honest snapshot of a “doomed project” struggling to conclude a niche franchise. Its legacy is one of fascinating ambition hamstrung by catastrophic development realities, making it one of the most compelling “kusoge” (awful yet interesting games) in the Falcom canon and a critical case study in asset reuse, corporate transition, and the fragility of creative vision.

Development History & Context: The Relics of a Collapsing Studio

To understand Rinne is to understand the terminal phase of Bothtec and the curious goodwill gestures of Falcom. Bothtec, the original creator of the Relics series (Relics: Ankoku Yōsai, Relics: The Recur of Origin, Relics: The 2nd Birth), was facing imminent bankruptcy in the early 2000s. As a final act, and perhaps as a thank-you to Falcom for publishing mobile ports of their titles, Bothtec reportedly handed over the in-progress fourth Relics project in its entirety to Falcom. This explains the game’s dual developer credit (Nihon Falcom Corp. and Bothtec, Inc.) on MobyGames and the complete erasure of Bothtec’s name within the game itself—likely due to trademark issues with the Relics name, which was not owned by either party cleanly.

The development context is written directly into the game’s code and assets. Rinne is visually Frankensteinian. It primarily uses upscaled, heavily pixelated sprites from Relics: The Recur of Origin and Relics: The 2nd Birth. More jarringly, its 3D models (used for sprites in a fixed isometric view) are ripped from Bothtec’s own cancelled Xbox project, Relics: The Absolute Spirit. This creates a stark visual dissonance: some enemies and character models have a cleaner, higher-polygon look that clashes with the grainier, older assets. The game feels like a “beta version” or a tech demo stitched together from a graveyard of abandoned projects—a impression reinforced by the sound design.

The music, composed by Falcom Sound Team jdk, is a mosaic of reuse. As documented, the soundtrack heavily features rearranged tracks that were unused prototypes from The Legend of Heroes: Trails in the Sky, Zwei!!, and even a track from the classic Xanadu. The in-game tutorial videos even use an earlier version of the first area’s theme. This recycling was likely born of budget constraints and time pressure, but it creates a bizarre, familiar-yet-alien auditory landscape. The soundtrack’s tone, as analyzed by VGM enthusiasts, is notably darker and more atmospheric than contemporaneous Falcom titles, leaning into new age and dark ambient textures—a tonal match for the game’s somber sci-fi narrative.

The timeline is critical: while the game’s menu claims 2004 and in-game text mentions 2002, its official release was June 30, 2005—the exact same day as Ys: The Oath in Felghana, one of Falcom’s most-celebrated and heavily marketed titles. Rinne received no marketing, was buried on release day, and Falcom has all but scrubbed it from official history. It receives no mention in series retrospectives, and its credits sequence is entirely absent, save for a single programmer’s name, Kouyou Suzuki, visible in a cutscene. This is the epitome of a “ghost game”: a title that exists in the record books but not in the corporate memory.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Simulation, Soul, and the Aftermath of War

Rinne‘s plot is a dense, philosophical sci-fi narrative that stands apart from the high fantasy of most Falcom works. It is set long after the events of The 2nd Birth. The planet, once the battleground for the ancient, warring alien races HEAVEN (mechanical lifeforms) and HELL (expert biologists), is now abandoned. A human military organization, MARX, has colonized the world and constructed a monumental virtual reality simulation—a “virtual playground”—to painstakingly recreate the history and conflict of these two factions, a process akin to Koji Suzuki’s novel Loop. Their goal is understanding.

To explore this VR, they create a special organic avatar, the Valkyrie, grown from the DNA of Hell’s Emperor. The prologue reveals a catastrophic transfer malfunction: Valkyrie’s physical body evolves into a monstrous, rogue form called Phobos and escapes, while his spirit, memoryless, is ejected into the real world. This spirit possesses a cloned child (the player’s initial host) and attempts to flee. During the pursuit, a second clone, Irian, aids the spirit but is wounded and captured by MARX forces. In a pivotal moment of pathos, MARX offers Irian’s life in exchange for the spirit’s cooperation: return to the virtual world as their explorer. Moved by her kindness, the spirit agrees. A new, default female Valkyrie body is provided, and the player’s journey begins.

Thematically, the game grapples with simulation vs. reality, the nature of identity, and the ethics of historical reenactment. The MARX project is not a neutral study; it is an attempt to weaponize or at least control the legacy of a destroyed civilization. The player, as a spirit inhabiting borrowed bodies, is constantly questioning what is “real” and what is programmed simulation. The “Body Snatch” mechanic is not just a gameplay tool but a narrative metaphor for displacement, colonization, and the loss of self.

The story’s structure is deceptively open. While not as sprawling as The Recur of Origin, it features meaningful branching paths based on player actions, particularly side-quests undertaken within the virtual world. Different NPC interactions, choices to help or ignore factions, and the ultimate resolution of key conflicts lead to multiple endings. The narrative’s outcome is determined not just by plot-critical decisions but by the aggregate of the player’s exploration and ethical choices, a sophisticated design for a game of its era and scale. The abundance of lore—through item descriptions, NPC dialogue, and environmental storytelling—paints a tragic picture of the Heaven/Hell war’s cyclical nature, suggesting the MARX simulation may be doomed to repeat it.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Possession-State Engine

The core of Rinne is its evolved, ruthless iteration of the Relics “Spirit Ride”/”Body Snatch” mechanic. The player controls a “spirit” that must constantly inhabit a physical body to exist. This spirit is anchored to a default Valkyrie form. Should the current host die, the spirit has 60 seconds to find and possess a new corpse—a tense, frantic “host-hopping” mechanic that raises the stakes dramatically compared to previous games, where death was often a simple reload.

Progression is entirely divorced from traditional experience points. Strength comes from possession, transformation, and synthesis. The system is built on several interconnected layers:

-

The Library of Possession: There are over 90 unique beings to possess across the HEAVEN, HELL, and MARX factions. Each body has inherent ranks (A, B, C, etc.), stats (HP, attack, defense, speed), special abilities, and attack patterns. Possessing a new body adds it to the Latency Menu—a bestiary of forms that can be summoned later.

-

Transform vs. Possession: The player cannot mix-and-match abilities from different bodies like in The 2nd Birth. Instead, the spirit must Transform into a specific, previously possessed form to access its full power set. The default Valkyrie form can only use a very limited set of hybrid, weak abilities. Mastery requires frequent swapping.

-

Spiritual Level & Synchro Gating: Possessing high-ranked bodies requires a sufficient Spiritual Level, a meta-progression counter that increases by gaining new forms. The maximum cap rises as the story progresses. Furthermore, to use a possessed form’s special abilities (beyond basic attacks), the player must fill a Synchro Gauge through combat with that specific form. This creates a loop: use a form to fight → fill Synchro → use its special move → gain more effective kills → potentially unlock new forms.

-

The Idol Summoning System: This is the major innovation over previous Relics titles. By finding special key items called Idols (which represent the three main races), the player can summon a companion from the Latency Menu into battle. This companion acts independently under AI control. Crucially, as corrected by GOG wishlist comments, the Idols are items you find; the NPCs you befriend (like Zip and Chimachima) are separate quest-givers. This system replaces the fixed party of earlier games, allowing for strategic summoning based on the encounter (e.g., summoning a flying HEAVEN unit to reach a platform, a heavy HELL brute for defense).

-

Puzzles and Traps: Rinne introduces environmental puzzles and traps (spikes, moving platforms, maze-like areas) that break up combat and require specific body abilities or transformations to solve—a HEAVEN laser to activate a switch, a small MARX scout to fit through a hole.

The design is brutally learning-oriented. The game does not hold your hand. Figuring out which body is needed for which puzzle or boss, managing the 60-second death timer while navigating a dungeon, and grinding Synchro for a crucial ability are all part of the harsh, rewarding loop. The goal of “Possess Them All” is not just a completionist trophy but a practical necessity for tackling the game’s diverse challenges.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Aesthetic Discordance and Atmospheric Depth

Visually, Rinne is its most divisive element. The isometric, fixed flip-screen presentation uses a mix of assets that tells the story of its development trauma.

* The Upscaled Past: Backgrounds and many sprites (items, lower-tier enemies) are from Relics: The Recur of Origin and The 2nd Birth, heavily upscaled. This results in a blurry, pixelated look that lacks the crispness of contemporary Falcom titles.

* The Xbox Ghost: Character models, bosses, and some environmental objects use the cleaner polygonal models from the cancelled Relics: The Absolute Spirit. These look sharper and more detailed but have a different artistic style—often more angular and darker—making them clash with the older sprites. It feels like playing two different games spliced together.

* Functional Improvements: This jumble has a perverse benefit: the larger sprites make small, interactable objects easier to see, and important objects are now highlighted, improving usability over the earlier, more obscure titles.

The world itself is the virtual simulation of a war-torn planet—a blend of fantasy and sci-fi. Areas range from organic, biological “HELL”-style caverns to geometric, metallic “HEAVEN” fortresses and the cold, tech-heavy MARX control zones. The atmosphere is one of eerie abandonment, perfectly suiting the narrative of studying ghosts. The disjointed graphics, rather than simply looking bad, inadvertently enhance the theme of a “botched” or “incomplete” simulation.

The sound design and music are arguably the game’s greatest unacknowledged strength. Falcom Sound Team jdk, featuring likely lead work by Maiko Hattori with contributions from Wataru Ishibashi and Hayato Sonoda, crafted a soundtrack that is dark, ambient, and deeply atmospheric. It relies on sparse piano, haunting synth pads, subtle fretless bass, and dissonant clusters. Tracks like b10 (mystical, driving rhythms), b20 (relaxing, with a great fretless line), b40 (unsettling piano), and b72 (mallet percussion and weird animal-like synth) demonstrate a maturity and restraint unusual for Falcom’s typically melodic, energetic style. This score doesn’t just accompany the game; it defines its somber, introspective, and often terrifying mood, turning visual shortcomings into an immersive, unsettling experience.

Reception & Legacy: The Quietly Preserved Obscurity

At launch, Rinne was a non-event. Released on the same day as the acclaimed Ys: The Oath in Felghana, with zero marketing and no official Falcom promotion, it vanished instantly. Critical reception was virtually non-existent; MobyGames lists no critic reviews and a minuscule number of player reviews and collectors (6-7). It was, for all intents and purposes, an immediate commercial failure and a forgotten footnote.

Its reputation has evolved within a tiny, dedicated niche. Among hardcore Falcom historians, VGM collectors, and fans of the “possess-em-up” genre, Rinne is revered precisely for its flaws. Its obscurity has made it a “holy grail” for preservationists. The discovery of its rich soundtrack—circulated in high-quality rips—has earned it a cult following in the video game music community, with Hattori’s work being singled out as a hidden gem in the Falcom catalog.

Its influence is indirect but significant. The Body Snatch/Transformation mechanics are a clear ancestor to later games like Carrion (as the monster) and the possession systems in Prototype. The idea of a character’s strength coming from absorbing the abilities of enemies, rather than leveling up, prefigures the “build” focus of many modern ARPGs. However, Rinne itself had no direct successors; it is the terminal point of the Relics series. The final game in a line that began on Japanese PCs, it died with its developer, Bothtec. References to it are scarce: a cameo of Brandish‘s Ares is a deep-cut Falcom easter egg, and the “Rinne” name would later appear in unrelated Rurouni Kenshin and DoDonPachi titles, but these are coincidental borrowings of the Japanese word for “reincarnation/cycle,” not acknowledgments of Bothtec’s game.

Its true legacy is as a cautionary tale and a trophy of preservation. It demonstrates how a game’s assets can outlive its studio and its intended design. It shows Falcom in a rare mode: not as a proud IP holder, but as a reluctant caretaker of another company’s troubled project, doing the bare minimum to see it released. The stark contrast between the game’s conceptual depth and its cobbled-together presentation is a lesson in the realities of game development where vision is often compromised by bankruptcy, deadlines, and corporate politics.

Conclusion: The Last, Lingering Echo of Relics

Rinne is not a good game by conventional standards. Its visuals are a patchwork, its UI is clunky by modern lights, and its difficulty often feels born of obfuscation rather than design. Its story is brilliant but buried under layers of confusion and minimal exposition. It is, in the words of Hardcore Gaming 101, a “game that was both abandoned during its creation and rushed while in production.”

Yet, to dismiss it is to miss its profound historical and artistic value. It is the definitive conclusion of the Relics series, carrying forward and refining its unique possession-based gameplay to a pinnacle of systemic depth (over 90 forms, Synchro gating, Idol summoning). Its narrative is a mature, melancholic sci-fi tale that tackles themes few RPGs, especially from Falcom, dared to approach in 2005. Its soundtrack is a masterclass in atmospheric composition that elevates the entire experience.

Most importantly, Rinne is an authentic time capsule. It is not a polished Falcom product; it is the raw, unfiltered output of a collapsing studio’s final assets, repurposed and released into the world with little ceremony. It represents a specific, dying moment in Japanese PC gaming—the twilight of the “so-called computer” (PC-98/Windows) era and the difficult transition to newer platforms. It is a collaboration born of desperation, a game that feels like a spirit—the spirit of Bothtec’s Relics vision—possessing the body of a different company’s resources to achieve a final, flawed, but fascinating form.

Final Verdict: Rinne is a 2/5 game as a playable experience for the average gamer, but a 10/10 as a historical document and curio. It is a must-study for game designers interested in possession mechanics and systemic depth, for Falcom completionists seeking the full—and often ugly—truth of the company’s history, and for preservationists committed to rescuing the fragments of lost development stories. It earns its place in history not as a classic, but as a critical, tangible artifact of an industry’s hidden layers—a phantom relic whose haunting is far more interesting than its polished contemporaries. Its final, quiet obscurity is the most fitting epitaph for a game about spirits trapped in simulated worlds.