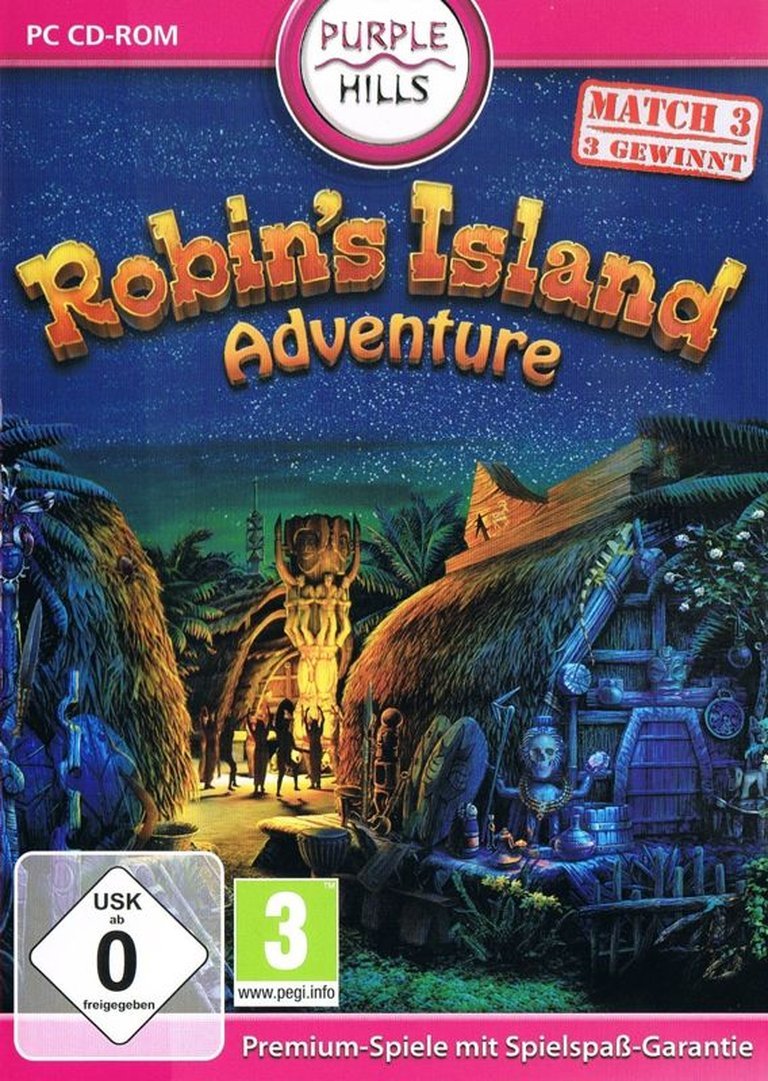

- Release Year: 2012

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: 1C Company, 1C Publishing EU s.r.o., HH-Games, Immanitas Entertainment GmbH, S.A.D. Software Vertriebs- und Produktions GmbH, Shaman Games Studio

- Developer: Shaman Games Studio

- Genre: Puzzle

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Gameplay: Hidden object, Mini-games, Tile matching puzzle

- Average Score: 57/100

Description

Robin’s Island Adventure is a first-person puzzle adventure game set on a mysterious, fog-covered island absent from all maps. After a shipwreck, the player assumes the role of a seafarer who must build essential structures like a house and boat to ultimately escape, all while helping the native islanders with their problems. Progress is achieved by completing match-3 tile puzzles to unlock hidden object scenes and mini-games, across 123 diverse levels in Normal and Time Challenge modes within an original game world featuring 18 building structures.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Robin’s Island Adventure

PC

Robin’s Island Adventure Guides & Walkthroughs

Robin’s Island Adventure: A Critical Autopsy of a Casual Puzzle Artifact

Introduction: Castaway in a Sea of Sameness

In the vast, ever-expanding archipelago of casual puzzle games, few titles drift as obscurely yet contentiously as Robin’s Island Adventure. Released in 2011 by the Russian studio Shaman Games and published by a consortium of companies including 1C Company and HH-Games, this title represents a peculiar transatlantic hybrid. It attempts to graft a narrative-driven, quasi-Robinsonade framework onto the then-dominant “match-3 + hidden object” casual game formula. This review argues that Robin’s Island Adventure is a fascinating case study in missed opportunities and genre-maximalism. While mechanically functional within its niche, it is fundamentally undermined by a profound dissonance between its aspirational narrative themes and its clumsy, often antagonistic, gameplay execution. Its legacy is not one of influence, but of caution—a testament to how a game’s own core design and protagonist can actively sabotage the very experience it seeks to create.

Development History & Context: The Russian Casual Explosion

Studio & Vision: Shaman Games Studio, based in Russia, was a prolific developer within the early 2010s casual game boom, specializing in hidden object puzzles (HOPA) and match-3 adventures. Their portfolio, visible through shared credits on MobyGames, includes titles like Sea Legends: Phantasmal Light and Dreamscapes: The Sandman. Robin’s Island Adventure fits squarely within this output, representing an attempt to create a more “adventure-like” casual game with a continuous plot. The credited project manager, Mikhail Alexandrov, and game designer, Sergey Gusev, were likely responsible for the core loop of matching objects to progress a building and narrative meta-game.

Technological & Market Context: Released in 2011, the game was built on the Unity 4 engine (as noted in Blacknut’s copyright line). This was a period of transition for casual games: they were moving from simple browser games to downloadable PC clients (like Big Fish Games’ manager) and early Steam offerings. The game’s system requirements (Pentium III 1 GHz, 256 MB RAM) are exceptionally low, targeting a broad, non-gaming audience—likely older players or those with older hardware. The market was saturated with match-3 hybrids (think Bejeweled twists and Diamond Mine clones), and Robin’s Island Adventure followed the template of using puzzle completion to fuel a larger goal, here a “shipbuilding” meta-progression.

Publishing Maze: The game’s publishing credits are unusually convoluted, listing S.A.D. Software, 1C Company, Shaman Games Studio, 1C Publishing EU, Immanitas Entertainment, and HH-Games. This suggests a complex international distribution deal common for Eastern European casual games at the time, where a local developer (Shaman) would partner with a large Russian publisher (1C) and multiple regional distributors (HH-Games for Western markets). This fragmentation may hint at a lack of a single, cohesive vision for the final product.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A White Savior in a Match-3 Fog

The narrative, cribbed from the Steam store page and expanded in the Gamepressure description, is straightforward: a young woman named Robin is shipwrecked on a mysterious Pacific island. She must aid the indigenous native tribe (referred to as “savages” in some descriptions, a problematic term), solve their problems, and ultimately build a ship to escape. Underpinning this is the stated goal of sharing “the achievements of Western European civilization.”

The White Savior Trope in Microcosm: The plot is a classic, un-ironic “white savior” narrative. Robin, a lone European, is positioned as the catalyst for the tribe’s progress and survival. She is the agent of “civilization,” teaching them carpentry and problem-solving. This colonialist subtext is made more jarring by the game’s cutesy, family-friendly aesthetic (PEGI 3 rating). There is no indication of cultural exchange as a two-way street; it is purely a transaction where Robin’s knowledge is the superior commodity for which she receives labor and resources.

The Protagonist Problem: A Case of Severe Identity Disruption: The most infamous—and critically damning—aspect of the narrative integration is Robin’s visual and auditory presentation, as meticulously dissected by the FlyingOmelette review. In cutscenes, Robin is depicted as a “young adult” capable of sailing and commanding a ship. However, on the actual match-3 game board, her sprite is that of a “tiny child… no older than five.” This isn’t just an artistic inconsistency; it’s a narrative and psychological disaster. A child cannot logically be the master carpenter and shipbuilder the story requires. The review’s observation that “a 5-year-old can’t sail a ship” is irrefutable. This cognitive dissonance completely hollows out the plot’s stakes. Why should we root for this child to “civilize” a tribe? The narrative collapses under the weight of its own visual storytelling.

Dialogue & Characterization: Based on available sources, dialogue appears minimal and functional, delivered through static cutscenes or text boxes. There is no evidence of nuanced character writing for Robin or the tribe members (including a “cunning shaman” antagonist). The tribe is a monolithic, passive group awaiting Robin’s intervention, reinforcing the problematic savior dynamic. The story serves only as a flimsy pretext to string together puzzle levels, with no meaningful character arcs or thematic exploration beyond the surface-level “help others to help yourself” premise.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Grind of Building a Dream

The gameplay is a hybrid structure that was common in casual games circa 2010-2015 but is executed here with notable flaws.

Core Loop & Progression: The player progresses through 123 levels divided into two modes: Normal and Time Challenge. The primary mechanic is match-3 (referred to in-source as “Tile matching puzzle”). Completing these levels is the sole means of earning resources (wood, stone, etc.) and special items used to construct 18 different “building structures” (a house, a boat, etc.). This “build your way off the island” meta-game is the game’s central hook, attempting to create a sense of cumulative progress and purpose missing from isolated match-3 games.

Hidden Object & Mini-Game Integration: As per the official description, completing match-3 levels grants access to “Hidden Objects and Puzzles.” These are interspersed as breaks in the match-3 progression. The hidden object scenes are described as exceptionally banal, with reused items and even misnamed objects (e.g., a “Barrel” item that is actually a treasure chest). The “puzzles” are noted as including sliding tile puzzles and jigsaws, Again, these feel like mandatory chores rather than engaging diversions. Their integration is purely transactional: complete them to get more resources, with no narrative or mechanical synergy.

Innovation & Flaws: The attempt to link a match-3 grind to a tangible building project was not unique but was a popular trend (e.g., Royal Envoy). However, Robin’s Island Adventure‘s implementation is criticized as “busywork.” The match-3 boards themselves are prone to being unwinnable without a “board re-roll” (a random reshuffle when no moves are available), substituting luck for strategy. A specific innovation—”animated tiles”—is noted as a hindrance when trying to match specific colors that animate under the cursor.

The UI and the “Robin Problem”: The most severe flaw is not a system but a character integration issue. On levels where Robin’s sprite is present on the board (as the avatar to be guided to an exit), she exhibits an extreme, annoying impatience. As described: “she will start fidgeting, yawning, and humming loudly, and she will do this constantly.” This is not a minor quirk; the review posits it as a game-breaking design choice. Her animations—triggered after mere seconds of player indecision—create a constant state of auditory and visual harassment. It frames the player’s thoughtful puzzle-solving as a nuisance to the protagonist, generating frustration and antipathy. This is a catastrophic failure of player-character rapport.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Pleasant Facade

Visual Direction: The game employs 2D, hand-drawn backgrounds. Descriptions call this “aesthetically pleasing” and “standard for casual adventures.” The art style is likely colorful, simple, and non-threatening, aiming for a broad, family-friendly audience. Screenshots (not available here but implied) would show tropical island scenery, native village huts, and simple character sprites. The inconsistency between cutscene Robin (adult) and gameplay Robin (child) is the most glaring artistic failure, suggesting disjointed asset creation or a profound lack of oversight.

Atmosphere & Sound Design: The soundtrack is described as “music inspired by the sounds of the jungle,” implying light, percussion-heavy, atmospheric tracks meant to evoke a tropical setting. Sound effects are listed separately in credits (FFFFBZ). The audio design seems conventional for the genre: pleasant but forgettable, serving only to backdrop the puzzles. The one notable, infamous sound is Robin’s impatient humming/fidgeting noises, which are described as relentless and maddening.

Cohesion: The world-building is paper-thin. The “original game world” claim is questionable; it’s a generic tropical island with generic “native” tropes. The art and sound create a superficially calm, adventurous atmosphere that is perpetually at odds with the irritations of the gameplay and the grating presence of the protagonist. The game’s aesthetic promises a relaxing escape, but the mechanics deliver a chore-filled, annoying experience.

Reception & Legacy: A Forgettable Footnote with a Warning

Critical & Commercial Reception at Launch: Critical reception appears virtually non-existent. Metacritic lists “no critic reviews” for the PC version. The only substantive critique is the FlyingOmelette review, which is scathing (1.5/5). Commercial data is sparse, but Steam charts show a “Mixed” rating (57/100 on Steambase from 60 reviews, with 66% positive from a smaller Steam-purchased sample). The game was clearly a niche product, sold primarily through casual game portals and as part of large bundles (the “Match 3 Bundle” on Steam includes it among 30 games). Its low price point ($6.99) and inclusion in bundles suggest modest sales driven by bundle deals rather than standalone demand.

Evolution of Reputation: Over time, the game has not been re-evaluated or rediscovered. It remains a forgotten title in the Steam libraries of bundle hunters and casual game completionists. Its reputation is cemented by that one devastating review, which, in the absence of any competing positive criticism, stands as the de facto canonical take. Forum discussions (Steam) are minimal and focus on minor bugs (misnamed items in HO scenes) and pleas for features like trading cards and achievements—requests that highlight its basic, un-politicized nature as a product, not a beloved experience.

Influence on the Industry: Robin’s Island Adventure has had no discernible influence. It did not innovate mechanically. Its narrative approach was too clumsy and ethically tone-deaf to inspire imitation. Instead, it serves as a negative data point. It demonstrates the perils of:

1. Narrative-Mechanic Dissonance: Building a plot around a protagonist whose in-game representation utterly contradicts the plot’s requirements.

2. Character Design as Antagonism: Creating a player-adjacent character whose sole function is to express irritation at the player’s actions.

3. Tokenistic World-Building: Using colonialist tropes without critique or depth in a genre not known for its stories, thereby amplifying harmful stereotypes unnecessarily.

It is a cautionary tale of how not to integrate a narrative into a mechanic-heavy casual game.

Conclusion: The Verdict on a Lost Cause

Robin’s Island Adventure is not a “bad” game in the sense of being technically broken or unplayable. Its match-3 mechanics are competent, if uninspired, and it delivers on the basic promise of 123 levels and a building meta-game. For a player seeking mindless, low-stakes puzzle consumption, it might suffice with the volume to mute the sound and ignore the story.

However, as a holistic video game experience, it is a profound failure. Its narrative is a regressive colonialist fable fatally undermined by the grotesque visual-age mismatch of its protagonist. Its gameplay is marred by a character so irritatingly designed that she actively diminishes player enjoyment. It represents a nadir of the “casual game” era’s sometimes-lax approach to narrative coherence and character empathy.

Its place in video game history is that of a specimen. It is a perfectly preserved example of a specific, problematic design philosophy prevalent in a subset of the early 2010s casual market: the belief that narrative could be a thin, Ishak over a mechanical grind, populated by characters designed more for demographic marketing than for logical or emotional consistency. It is a game remembered not for its joys, but for its iconically annoying hero and the chillingly apt observation that a game’s own protagonist finds its core activity boring. In the canon of interactive entertainment, Robin’s Island Adventure is a shipwreck from which no one—not even the fictional Robin—should bother to salvage any parts. It is a curiosity, a lesson, and ultimately, a deeply forgettable entry.