- Release Year: 2014

- Platforms: Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4, PS Vita, Windows

- Publisher: 5pb. Inc., Digital Touch Co., Ltd., MAGES. Inc., Spike Chunsoft Co., Ltd., Spike Chunsoft US

- Developer: MAGES. Inc., Nitroplus Co., Ltd.

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 1st-person, 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Visual novel

- Setting: Fantasy, Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 83/100

Description

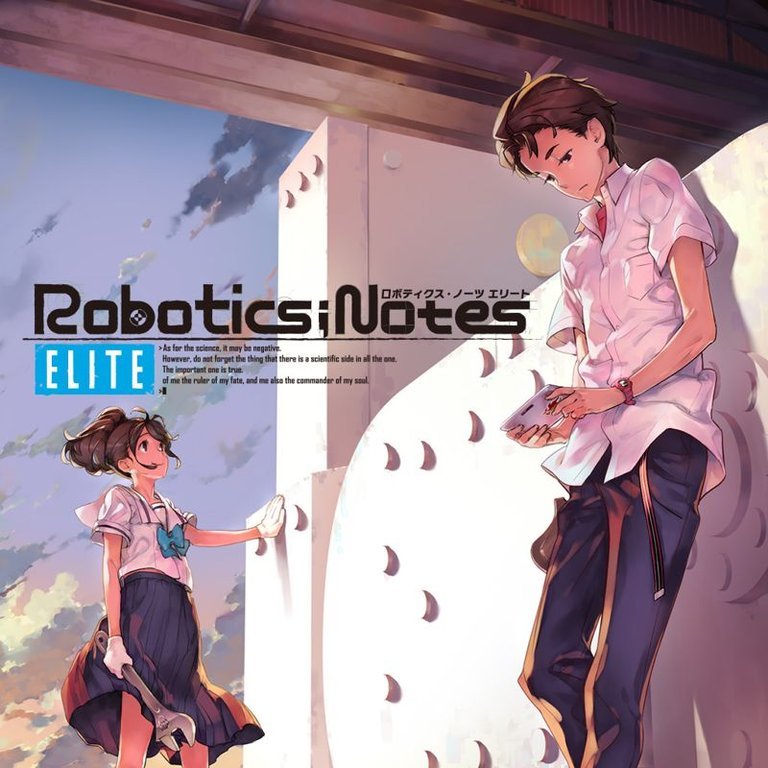

Robotics;Notes Elite is an enhanced remake of the original visual novel Robotics;Notes, set in a near-future sci-fi world where high school students pursue robotics projects and uncover scientific mysteries. Part of the acclaimed Science Adventure series, it features improved 3D models, additional scenes, and a reconstructed storyline with elements of mecha and narrative-driven gameplay.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Robotics;Notes Elite

PC

Robotics;Notes Elite Mods

Robotics;Notes Elite Guides & Walkthroughs

Robotics;Notes Elite Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (82/100): With impeccable detail and character work, this twisty tale manages to combine heartfelt down-to-earth character relationships and truly fascinating science fiction conspiracies without dropping the ball on either count.

rpgfan.com : Robotics;Notes ELITE helped me remember the joy of robots, the joy of creation, and put simply, the joy of science.

kirikiribasara.com : The character development in the story is believable and very human—there are many points throughout the story where you can’t help but root for the main characters as they tackle a particularly difficult challenge to their identities, their goals, and their dreams.

opencritic.com (84/100): Tanegashima offers a more relaxed adventure in the Science Adventure universe and is more than worth your time reading.

Robotics;Notes Elite: Review

Introduction: The Island of Dreaming Giants

In the pantheon of visual novels, few series command the reverence and scrutiny of the Science Adventure franchise. From the temporal paradoxes of Steins;Gate to the psychological horror of Chaos;Head, the series established a brand of “99% science, 1% fantasy” storytelling that prioritizes conceptual rigor alongside emotional fervor. Enter Robotics;Notes Elite, the 2014 enhanced port of 2012’s Robotics;Notes, which represents a pivotal, if divisive, evolution for the series. It is a game that trades the conspiratorial dread and existential terror of its predecessors for a narrative steeped in youthful ambition, engineering perseverance, and the tangible joy of creation. Set against the serene backdrop of Tanegashima Island, it asks a deceptively simple question: “What would happen if you really tried to make a giant robot?” The answer, as this review will exhaustively demonstrate, is a story that is at once reassuringly grounded and ambitiously speculative, a visual novel that pushes interactive storytelling mechanics in novel directions while occasionally stumbling under the weight of its own structural complexities. This is not merely an entry in a series; it is a deliberate thematic detour that redefines what a “Science Adventure” can be, championing the heartbeat of human collaboration over the cold logic of cosmic horror.

Development History & Context: Forging a New Kind of Science Adventure

The genesis of Robotics;Notes lies with Chiyomaru Shikura, CEO of MAGES. (formerly 5pb.), the architect of the entire Science Adventure universe. Planning and conceptualization began as early as July 2010, with the project publicly announced on December 22 of that year. Shikura’s vision was explicit: to create an “Augmented Science Adventure” (拡張科学アドベンチャー, Kakuchō Kagaku Adobenchā). This moniker signified a shift from the series’ prior foci—mind control and time travel—to the proximate, pervasive technologies of augmented reality (AR) and robotics. The goal was to ground the fiction in technologies that felt imminently possible, a philosophy embodied by the team’s unprecedented collaboration with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). This partnership lent authenticity to the game’s depictions of rocketry, space center operations, and the logistical realities of large-scale engineering, anchoring its wildest conspiratorial leaps in a framework of tangible science.

Development was a joint effort between MAGES. and Nitroplus, the latter having contributed to all prior SciADV mainline titles. The production team, led by producer Tatsuya Matsubara and scenario writer Naotaka Hayashi, faced a significant technical mandate: to realize Shikura’s “high-quality 3D” ambition. Drawing inspiration from games like Catherine and The Idolmaster 2, they opted for fully 3D animated character models instead of the 2D sprites used in Chaos;Head and Steins;Gate. This was a risky, resource-intensive choice for a visual novel, but it allowed for fluid posing, dynamic camera work, and a more cinematic presentation that would become a hallmark of the Elite version. The original game launched for PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 in Japan on June 28, 2012, selling over 80,000 copies in pre-orders—a figure that notably exceeded Steins;Gate‘s initial surge, signaling fervent audience appetite.

The “Elite” iteration arrived on PlayStation Vita on June 26, 2014. It was not a full remake like Steins;Gate Elite, but a substantial enhanced port. It featured:

* Remodeled 3D character models with higher resolution textures.

* Animated cutscenes integrated from the 2012 Production I.G. anime adaptation.

* Script revisions aimed at improving pacing, particularly in Phase 1.

* Additional scenes and refined presentation.

This version formed the basis for all subsequent Western releases: it was ported to Nintendo Switch and PlayStation 4 (as Robotics;Notes Elite HD) in Japan in 2019, and localized by Spike Chunsoft for a worldwide release on October 13, 2020 (October 16 in Europe) for PC (via Steam), Switch, and PS4, often bundled with the sequel DaSH. The Elite version, therefore, represents the canonical, most accessible experience for international audiences, a bridge from the niche Vita audience to modern platforms.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Human Machinery of Hope

Plot Architecture: Phases, Reports, and Canonical Routes

Robotics;Notes unfolds on Tanegashima Island in 2019, nine years after the world-line alterations of Steins;Gate (the “Steins Gate” world line). The protagonist is Kaito Yashio, a top-5 ranked player in the fictional fighting game Kill-Ballad 3D and a profoundly reluctant member of the nearly defunct Central Tanegashima High Robot Research Club. The de facto leader is his childhood friend, Akiho Senomiya, a force of optimistic determination whose dream is to complete the life-sized Gunbuild-1 robot, a project started by her older sister, Misaki. The club’s survival hinges on this audacious goal.

The narrative is structured into twelve “Phases,” a deviation from the traditional “common route + character routes” model. Crucially, all routes are canon and occur in a linear chronological order. You cannot see a “later” Phase without first completing the preceding ones, but the mechanism to unlock them is non-standard. Progress hinges on interacting with the PhoneDroid, Kaito’s tablet, and its “PokeCom Trigger” system. This interface houses three key applications:

1. Deluoode Map: A standard map.

2. Twipo: An in-game social network (a clear analog to Twitter). Interacting with posts—replying correctly to specific “tweeps” from club members—sets flags that unlock subsequent Phases.

3. Iru-o: An AR image recognition app. The player must use this to scan environments, finding camouflaged “Kimijima Reports”—digital annotations containing fragments of a global conspiracy.

The plot escalates from club-management sim to world-threatening thriller. Kaito discovers the Kimijima Reports, authored by the deceased scientist Kō Kimijima, which initially warn of a solar flare catastrophe. Assisting him are two AI personalities within Iru-o: the helpful Airi and the sinister Sister Centipede. The mystery deepens: Airi is based on a real girl, Airi Yukifune, placed in suspended animation. The reports are a manipulation; Kimijima, now a digital ghost within Iru-o, works for the Committee of 300, a shadowy cabal. His true plan, “Project Atum,” is to trigger an apocalyptic solar flare via a rocket launch from the Tanegashima Space Center, enabling the Committee to rule a depopulated world. Kimijima murders the club’s benefactor Mizuka Irei, brainwashes Misaki, and seizes the experimental battle robot SUMERAGI to destroy the club’s progress.

The resolution requires the entire island community. With help from Nae Tennouji (returning from Steins;Gate) and the resistance leader Toshiyuki Sawada, the club upgrades the Gunbuild-1 into the Super Gunbuild-1. In the climactic battle, Kaito pilots it against the SUMERAGI. The victory hinges not on firepower alone, but on Daru (Itaru Hashida)—now a member of Sawada’s group—creating a virus to delete Kimijima’s AI consciousness. The rocket is aborted, the Committee’s plan foiled, and the club is hailed as heroes. The ending is optimistic but leaves the door open, noting Kimijima’s boast that “another copy will surely surface.”

Characters as Thematic Vessels

The true genius of Robotics;Notes lies not in its global conspiracy, but in its character ensemble. Each core club member embodies a specific, deeply human struggle that thematically resonates with the game’s core question about building giants.

* Kaito Yashio: The “master of his fate” in a literal sense, he suffers from the MF Anemone Incident—a traumatic event that gave him “time dilation” spasms (time seems to slow). His arc is about moving from passive escapism (Kill-Ballad) to active responsibility. His journey asks: What do you fight for when the fight isn’t a game?

* Akiho Senomiya: The embodiment of passionate perseverance. She is “the captain of her soul,” relentlessly pursuing her sister’s unfinished dream despite engineering setbacks, financial woes, and societal ridicule. Her character argues that analog creation—the sweat, grease, and manual labor of building—is a redemptive act in a digital age.

* Subaru Hidaka: The prodigy constrained by legacy. A former Robo-One champion, he is bound by a promise to his fisherman father to abandon robotics. His conflict is between genetic destiny and personal passion, resolved through the club’s inclusive, hobbyist ethos.

* Junna Daitoku: A karate practitioner with robophobia stemming from a childhood accident. Her arc is about confronting fear and finding strength in a supportive community, proving that physical and mental fortitude are not opposites but complements.

* Frau Koujiro (Kona Furugōri): The reclusive creator. The anonymous developer of Kill-Ballad and an infamous otaku, she communicates only online. Her quest to find her missing mother forces her to reconnect with the physical world, exploring themes of digital isolation versus human connection.

Supporting characters like the guilt-ridden Mizuka Irei, the brainwashed Misaki Senomiya, and the antagonistic AI Kimijima (a man who sought to control humanity’s fate) form a web of consequence and loss. The Committee of 300 plot serves as an externalization of the internal pressures the characters face: societal control, predetermined paths, and the fear of failure. The narrative thesis becomes clear: the greatest obstacle to building a giant robot (or changing your life) is not technical impossibility, but personal doubt and unresolved trauma.

Thematic Synthesis: Wholesome Sci-Fi

Where Steins;Gate grapples with the burden of salvation and Chaos;Head with delusional identity, Robotics;Notes is, in the words of one critic, “more emotive and evocative.” Its central theme is the virtue of trying. The “science” is robotics and AR, but the “adventure” is emotional. The game celebrates hobbyist enthusiasm, the joy of the workshop, and the messy, collaborative process of creation. It contends that the pursuit of a seemingly impossible dream—even if the final product is a compromised “Gunbuild-1″—has intrinsic value. The AR technology, represented by Iru-o, is a double-edged sword: a tool for investigation and connection, but also a vector for the Committee’s manipulation and the “Kill Balloon” phenomenon (where people become apathetic drones glued to AR overlays). The story ultimately posits that technology is neutral; its moral weight is determined by human intent—whether used to build a robot or to control minds.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Interactivity Experiment

The Visual Novel Core

Fundamentally, Robotics;Notes Elite is a visual novel. The player spends the majority of time reading text accompanied by 3D animated character models on 2D backgrounds. These models fluidly shift poses and expressions, a significant upgrade from the sprite-based animation of earlier SciADV titles. CG artwork appears at key moments for dramatic emphasis. The experience is heavily text-driven, with full voice acting in Japanese (the English localization offers only subtitles, a point of note for some fans).

The PhoneDroid & Interactive Systems

What elevates Robotics;Notes from a pure reading experience is the PhoneDroid interface, accessed via the PokeCom Trigger. This system integrates gameplay directly into the narrative flow in three primary ways:

-

Twipo (Social Media Interaction): This is the route progression mechanic. Periodically, characters post to Twipo. The player can choose to reply (or not) with one of several pre-set responses. The correctness and timeliness of these replies determine which subsequent “Phase” (character-focused route) becomes available. This is the game’s most infamous and divisive design choice. As detailed by critics, the system is opaque and punitive. The game provides no clear guide to which replies unlock which routes. Since all routes are canonical and must be played in a specific order to reach the true ending, players are forced into a cycle of trial-and-error backtracking. You finish one route, return to the title screen, must manually load a previous save from a specific “branch point,” and guess which Twipo interactions are needed for the next route. This butchers pacing and is universally cited as the game’s greatest flaw, often requiring a walkthrough to avoid hours of frustration.

-

Iru-o (AR Scanning & Kimijima Reports): This is the puzzle-solving mechanic. At numerous points, the narrative tasks Kaito with finding hidden Kimijima Reports on Tanegashima. The player must switch to the Iru-o app, scan the current background environment, and hunt for camouflaged, semi-transparent annotations that distort based on their surroundings. These are often tiny and obscured, requiring meticulous examination of scenes. Failure to find a required report blocks story progression. While thematically brilliant—making the player engage with the world as Kaito does—the execution is obscure and tedious, again leaning heavily on guides or obsessive pixel-hunting.

-

Kill-Ballad Mini-Game: Interspersed throughout are brief, arcade-style robot fighting sequences from Kaito’s favorite game. These are simple quick-time event affairs, requiring the player to input commands as they flash on screen. They provide a fun, kinetic break from the reading but have no bearing on the main plot or club’s construction progress. They are purely atmospheric and表征 Kaito’s expertise.

Robot Construction: Simulation as Narrative Backdrop

A unique element is the ongoing Gunbuild project. The narrative constantly references the Robotics Club’s practical challenges: fundraising, sourcing parts from local shops like “Robo Clinic,” dealing with engineering compromises (they can’t perfectly replicate the fictional Gunvarrel), and preparing for the Robo-One Grand Prix competition. However, this is entirely abstract. There is no dedicated robot-building simulator or management layer. The construction is told through dialogue, cutscenes, and occasional status updates. The player does not assemble the robot; the story tells you they did. This is a narrative choice emphasizing the process and the people over a gameplay mini-game, but it may disappoint those expecting more hands-on mechanics.

Structure & Pacing: A Deliberate Ascent

The game’s structure is linear with mandatory side-routes. The “Common Route” (Phases 1-11) establishes the club and introduces the conspiracy. Twelve dedicated character phases (one for each main heroine and key side character) must be completed in a specific sequence to unlock the final, “true” Phase 13. This design intends to make every route canon and necessary, feeding pieces of the Kimijima conspiracy mystery to the player incrementally. The pacing is famously deliberate, with the first 80% devoted to slice-of-life, club dynamics, and slow-burn mystery. The final act, where the Committee’s plan erupts and the Super Gunbuild-1 battle occurs, is fast-paced and action-packed, but some critics felt the true ending itself is rushed after such a long buildup.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Tanegashima Aesthetic

Setting: A Island of Contrasts

Tanegashima is not merely a backdrop; it is a character. A real island in southern Japan hosting the Tanegashima Space Center, the setting embodies the clash between rural tranquility and cutting-edge technology. The world is one where AR (“PokeCons”) is ubiquitous, giant robot anime (Kill Ballad, Gunvarrel) inspire real-world engineering clubs, and space development (discussions of space elevators, Mars colonization) is a local economic driver. This grounded, near-future sci-fi (2019) makes the global conspiracy feel plausible. The omnipresence of AR technology allows for the Iru-o mechanics to feel natural rather than gimmicky. The island’s insular community is crucial; the final act relies on collective action, with townsfolk rallying to support the club, making the victory feel communal and earned.

Visual Direction: The 3D Evolution

Robotics;Notes Elite’s defining visual trait is its use of fully voiced, 3D polygonal character models. This was a technical statement for the 2012 original and is refined in Elite. The models are expressive, capable of nuanced facial animations and dynamic posing during conversations, breaking the static “visual novel” stereotype. The Elite version’s models are cleaner, with higher-resolution textures. The integration of anime cutscenes from the Production I.G. adaptation into key moments (explosions, dramatic reveals, the final battle) provides cinematic punctuation that the original’s static CGs could not. The background art effectively paints Tanegashima’s landscapes—coastal roads, the space center, school clubrooms—with a mix of realistic detail and anime stylization. The overall aesthetic is one of bright, clean, and optimistic sci-fi, a visual thesis that “the future is being built by enthusiastic kids.”

Sound Design: Abo’s Emotive Score

Takeshi Abo, the series’ iconic composer, returns to craft a soundtrack that perfectly mirrors the game’s dual nature. The score swells with soaring, hopeful themes during club meetings and robot construction, evoking wonder and ambition. It shifts to tense, pulsing electronic tracks during Kimijima Report discoveries and conspiracy unraveling. The opening themes differ between versions: the original uses “Kakuchou Place” (Zwei), while Elite uses “Yakusoku no Augment” (Zwei), both capturing the “augmented” essence. The music is less about standalone memorability and more about emotional underscoring, supporting the narrative beats without overwhelming them. The full Japanese voice cast, featuring talents like Ryohei Kimura (Kaito) and Yoshino Nanjō (Akiho), delivers performances that are widely praised in the localization for their ability to convey both the characters’ youthful energy and their deeper pains.

Reception & Legacy: The Wholesome Middle Child

Critical Reception at Launch and in the West

Robotics;Notes (2012) and Robotics;Notes Elite (2014) received strong critical scores in Japan. Famitsu awarded the Vita port a respectable 30/40. Western reviews for the 2020 Elite localized release were similarly generally favorable, with aggregate scores around 84% on OpenCritic and 82/100 on Metacritic (PC). Critics were almost unanimous in praising:

* The Character Ensemble: Universally hailed as “impeccable,” “well-developed,” and more “grounded” than previous SciADV casts. The shift to personal, relatable struggles over cosmic horror was seen as a refreshing strength.

* The Narrative’s Emotional Core: The blend of slice-of-life club dynamics with sci-fi conspiracy was frequently described as “wholesome,” “emotive,” and a successful balance. The theme of “overcoming personal failings” resonated deeply.

* The Presentation: The 3D models, integrated anime cutscenes, and overall polish were noted as significant improvements over the original.

The criticisms were consistent and targeted:

1. Obtuse Route Progression: The Twipo-based flag system was lambasted as “frustrating,” “counter-intuitive,” and a severe pacing killer that necessitates guides. Critics from RPG Site, RPGFan, and Kiri Kiri Basara explicitly stated this structural flaw marred an otherwise excellent experience.

2. Deliberate (to a Fault) Pacing: The long, detailed buildup in the first two-thirds was seen by some as slow, with a rushed ending that couldn’t fully metabolize all its established threads.

3. Inconsistent Mystery Depth: Compared to the intricate, mind-bending puzzles of Steins;Gate, the Kimijima Report conspiracy was sometimes perceived as having less “meat on the bone,” with a final villain whose motives, while clear, lacked the philosophical complexity of prior antagonists.

Commercial Performance & Audience Divide

Commercially, the original 2012 release had a strong start (~69,000 physical units first week), but sequel DaSH (2019) saw a significant drop (~3,900 units first week), reflecting a narrower, more dedicated fanbase. The 2020 Western Elite release performed adequately on Steam (estimated ~18k units, ~$431k revenue), a solid figure for a niche visual novel.

Within the fan community, Robotics;Notes occupies a complex space. It is often ranked below Steins;Gate and sometimes Chaos;Head in franchise tier lists. The anime adaptation is a major point of contention; many fans consider it a poor condensation that rushes the plot and diminishes Kaito’s internal monologue and the route structure, recommending the visual novel as the definitive experience. The Elite version is broadly respected as the superior way to engage with the story. Debates persist: is its “wholesome” tone a breath of fresh air or a retreat from the series’ signature intensity? Does its focus on “the joy of creation” elevate it or dilute the SciADV brand? The sequel, DaSH, is often viewed more critically as a fandisc with a contrived crossover plot, though its canonical ending ties back to the broader series lore.

Position in the Industry & Series Legacy

Robotics;Notes Elite’s legacy is multifaceted:

1. Technical Innovation in VNs: It was an early and notable attempt to integrate 3D models and AR simulation mechanics directly into a visual novel’s narrative fabric. While the execution of puzzles was flawed, the ambition to make the player “use” a phone interface to affect progression was influential.

2. Thematic Diversification: It proved the Science Adventure formula could support a non-horror, optimistically sci-fi story. It expanded the series’ emotional range, demonstrating that its core mechanic—using science as a lens for human drama—could explore joy, perseverance, and community as powerfully as despair and paranoia.

3. A Bridge to New Audiences: Its themes of robotics, mecha, and school clubs are more accessible to fans of anime like Gundam or Darling in the FranXX than the dark psychological or complex scientific concepts of other entries. The 2020 localization, bundled with DaSH, was a strategic move to capitalize on the growing Western visual novel market.

4. Cautionary Tale on Interactivity: Its route-unlocking system serves as a textbook example of how obscure event flags can damage pacing and player agency. It highlighted the need for clearer integration of choice mechanics in branching narratives.

Conclusion: An Imperfect Masterpiece of Heart and Mechanism

Robotics;Notes Elite is a game of profound contradictions. It is a Science Adventure title that feels fundamentally unlike its siblings, trading existential dread for heartfelt camaraderie. It is a visual novel that innovates with interactive phone systems but hobbles its own flow with impenetrable flag mechanics. It is a story with a sprawling, 50-hour narrative whose most memorable moments are quiet character beats, not world-ending explosions.

Its definitive verdict must be contextual. For the genre skeptic, it is perhaps the most accessible entry in the SciADV pantheon—a coming-of-age story with a sci-fi shell that celebrates passion over paralysis. For the series devotee, it is an essential, thematically vital installment that deepens the universe’s lore while showcasing MAGES.’s willingness to evolve. It is not as tightly wound or philosophically dense as Steins;Gate, nor as brutally intense as Chaos;Child. Instead, it offers something rarer: a story about building something—a robot, a friendship, a future—amidst the noise of a conspiratorial world.

The flaws are indelible. The Twipo system is a design wart that demands external guidance. The pacing in its first half will test the patience of those expecting constant thriller beats. The ending, while satisfying, cannot fully resolve the magnitude of its own setup. Yet, to dismiss Robotics;Notes Elite for these failings is to miss its singular achievement: it makes you believe, with every fiber of its being, in the heroism of the workshop, the nobility of the hobbyist, and the idea that saving the world might start with a girl in a clubroom refusing to let her dream be dismantled.

In the canon of video game history, Robotics;Notes Elite stands as a landmark of thematic ambition and technical experimentation within the visual novel medium. It dared to ask if a story about building a giant robot could carry the weight of a franchise defined by saving reality itself, and its answer—a resounding, heartfelt, and occasionally frustrating yes—cements its place as a beloved, flawed, and essential chapter in the ongoing saga of the Science Adventure. It is a game that understands the ultimate truth of its own title: the most advanced robotics are not metal and circuits, but the mechanisms of human will. 8.5/10 – A flawed gem whose heart beats stronger than its technical stumbles.