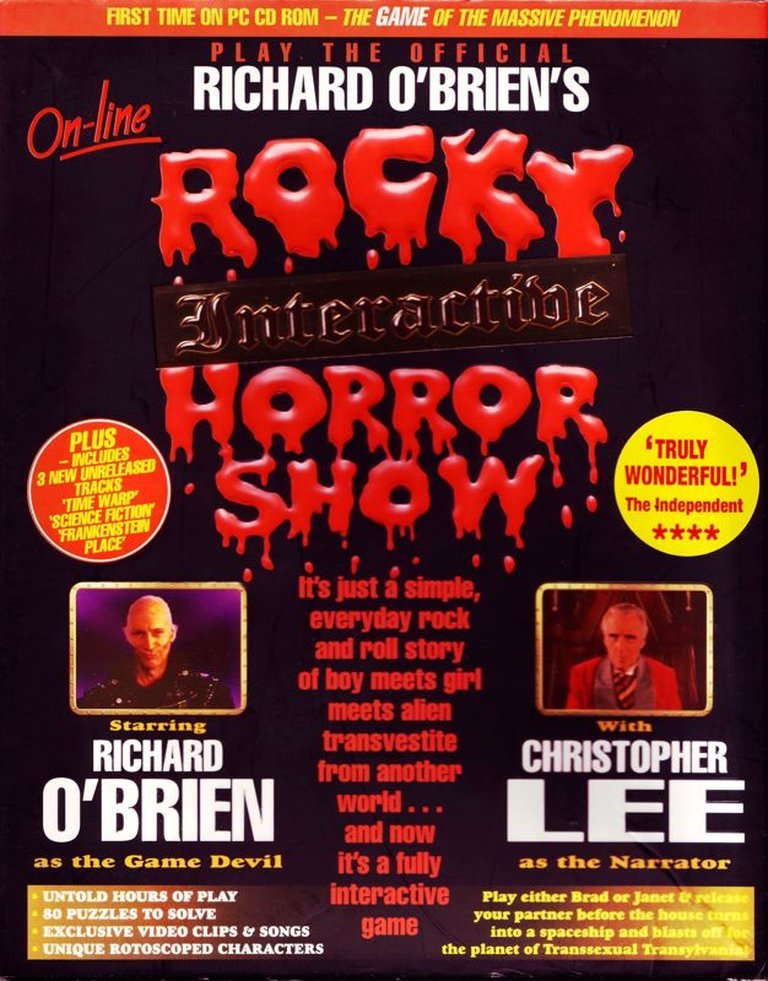

- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: On-Line Entertainment Ltd.

- Developer: On-Line Entertainment Ltd.

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Hotseat

- Gameplay: Puzzle elements

- Setting: House, Spaceship, Transsexual Transylvania

- Average Score: 90/100

Description

Based on the cult classic musical The Rocky Horror Show, this 1999 adventure game tasks players with choosing to play as Brad or Janet, one of whom is turned to stone by the ‘Medusa machine’ at the doorstep of Frank N. Furter’s alien-filled mansion. The remaining partner must rescue their lover within 30 minutes by collecting over 80 puzzles and nine Demedusa pieces before the house transforms into a spaceship and departs for Transsexual Transylvania, all while navigating with keyboard controls and encountering narration by Christopher Lee and deceptive interference from Richard O’Brien as the ‘Game Devil’.

Gameplay Videos

Rocky Interactive Horror Show Guides & Walkthroughs

Rocky Interactive Horror Show Reviews & Reception

imdb.com (100/100): Very Rocky Horror. Not many games sweat the license.

metacritic.com (80/100): A nice little game that’s not too pricey, not overly long but a decent bit of fun.

gamesreviews2010.com : The Rocky Interactive Horror Show Game was a critical and commercial failure.

Rocky Interactive Horror Show: A Cult Adapter’s Tumultuous Time Warp

Introduction: The Castle’s Echo

To approach Rocky Interactive Horror Show is to step through a looking glass warped by time, technology, and transgressive camp. Released in 1999 for Windows, this game represents a curious nodal point in two distinct histories: the ongoing, lucha libre-style grappling with adapting The Rocky Horror Picture Show into interactive media, and the late-1990s twilight of the point-and-click adventure genre. Developed by On-Line Entertainment in conjunction with Transylvania Interactive, it serves as a spiritual successor to the 1985 CRL Group text adventure, inheriting its premise but transplanting it into a graphically richer, yet fundamentally awkward, 2D adventure engine. Its legacy is not one of mainstream acclaim or commercial success, but of passionate polarization—a title that divides critics between those who see a charming, faithful mess and those who see a clumsy, obsolete relic. This review argues that Rocky Interactive Horror Show is a fascinating failure: a game whose profound technical and design shortcomings are inextricably woven into its authentic, if often misguided, attempt to capture the anarchic spirit of its source material. It is less a game and more a curated experience—a haunted house attraction built with questionable materials, where the creaks and groans of the infrastructure become part of the spooky show.

Development History & Context: From Jaguar Ghost to Windows Wraith

The saga of Rocky Interactive Horror Show is a parable of 1990s gaming volatility. The project was initially announced in 1995 not as a PC game, but as a title for the commercially doomed Atari Jaguar CD, with plans for a PC version to follow. This was a period of extreme turbulence for Atari Corporation, which saw the Jaguar fail catastrophically, its newly formed PC publishing arm (Atari Interactive) shuttered, and the company itself merged into JT Storage in a reverse takeover by April 1996. As detailed in Wikipedia and corroborated by archival sources like Atari Explorer Online, the Jaguar CD version was among the many casualties, and the PC version was shelved. Former Atari designer Dan McNamee’s 2018 interview confirms his involvement as associate producer alongside the legendary Richard O’Brien before the layoffs. The rights and project eventually found their way back to the original UK developer, On-Line Entertainment, which released it in Europe on March 1, 1999, with a North American release following in November 2000. A PlayStation conversion was announced but never materialized.

Technologically, the game was trapped between eras. Its 2D, pre-rendered or static background aesthetic with character sprites was already looking dated in 1999, a time when 2.5D (like Grim Fandango) and full 3D (like Half-Life) were defining adventure and action games. The engine evokes comparisons to LucasArts’ Maniac Mansion (1987), placing it stylistically a decade behind. Yet, it also incorporated then-cutting-edge CD-ROM features: full-motion video sequences (FMV) with Richard O’Brien and Christopher Lee, and an audio CD-component featuring unreleased tracks and acoustic performances, making the disc itself a hybrid介质. The development context explains its visual lethargy: a project borne in the mid-90s, delayed by corporate collapse, and finally released into a market that had moved on, yet still clinging to its cult license with fierce loyalty.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Plot Held in Stone

The narrative framework is a direct, functional lift from the 1975 film. The player selects either Brad Majors or Janet Weiss at the outset. Almost immediately, the unchosen partner is petrified by Dr. Frank-N-Furter’s “Medusa Transducer” on the castle’s doorstep. The chosen protagonist must then infiltrate the mansion, solve a sprawling series of puzzles, and collect the nine pieces of the “Demedusa machine” to reverse the transformation—all within a real-time 30-minute limit before the house becomes a spaceship and departs for the planet Transsexual Transylvania.

What sets the game’s narrative apart is its meta-textual framing device. The story is presided over by two supernatural narrators:

* The Narrator (Christopher Lee): Cast in the role originated by Charles Gray in the film, Lee delivers gravitas with a deliciously straight face. His announcements and occasional hints provide a搓衣板 of eerie convention amidst the chaos.

* The Game Devil (Richard O’Brien): The creator of the franchise plays a trickster god, directly addressing the player to mock, mislead, and revel in the absurdity. This is not Riff-Raff, but O’Brien as the ultimate authorial presence, reminding players that they are in a game, and a Rocky Horror one at that.

This duality creates the game’s primary thematic tension: a struggle between order (the ticking clock, the puzzle-solving goal imposed by Lee’s narration) and glorious, sanctioned anarchy (the surreal obstacles, the game-breaking humor offered by O’Brien). The plot itself is a stripped-down skeleton; character interaction is minimal, and the film’s iconic musical numbers are largely absent from the gameplay proper, a point of lament from reviewers like Rosemary Young (Metzomagic). The true “narrative” emerges from the player’s interaction with the environment—a surreal scavenger hunt through a castle populated by bizarre residents and traps. The ending, requiring the assembly of the Demedusa puzzle and a final sub-game, promises a resolution but feels more like an escape from a sensory overload than a narrative climax.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Clockwork Square

The core gameplay loop is a classic graphic adventure templated on Maniac Mansion: navigate 2D screens, collect items, use them on other items or environments to solve puzzles, and avoid antagonists. However, Rocky Interactive Horror layers on several idiosyncratic and contentious systems:

-

The Tyranny of the Clock: The 30-minute real-time limit is the game’s most defining—and divisive—mechanic. It creates relentless pressure, forcing players to prioritize and often ignore exploration. Time can be extended by finding “red lips” scattered about and by securing Demedusa pieces, but the constant tick of the clock (displayed prominently) induces anxiety. Critics like IGN’s Scott Steinberg saw this as a plodding pace-setter, while fans of challenge might see it as a necessary tension. As noted on Metzomagic, the limited save slots (10, with overwriting) exacerbate this stress, forcing strategic save management.

-

Keyboard-Centric Control: Contrary to some descriptions, the game is not point-and-click. MobyGames and the official description explicitly state it is “completely controlled by keyboard,” using arrow keys for movement, spacebar for interaction/pick-up, and other keys for inventory management. This was a deliberate, console-port-friendly design choice (despite never appearing on console), but it resulted in a “temperamental interface” (Quandary). Navigating precise positions for actions is fiddly, and the lack of mouse support is a major point of critique from modern sensibilities.

-

Puzzle Philosophy: The game boasts “over 80 puzzles” and nine Demedusa pieces. These range from logical inventory combinations (e.g., making a lizard skin handbag for Frank) to surreal, arithmetic-based challenges (cracking a safe with arrow key combinations) and rhythm-based sequences (performing the steps of the Time Warp dance in the Disco Room to retrieve Rocky’s brain). The puzzles are a mixed bag: some are cleverly themed, while others are “obscure” or “dröge” (PC Joker). Their variety is a strength, but their opacity, especially without the bundled walkthrough (a telling inclusion), is a significant barrier.

-

Hazard & Hindrance: Frank-N-Furter’s minions are not just scenery. Magenta and Columbia will strip the player of their clothes, forcing a retrieval mission (naked characters cannot pick up items, as they are “too intent on shielding their important bits” – GamesDomain). Riff Raff and Eddie can “zap” the player to the infirmary, costing precious time. These are not death states but time penalties and inventory disruptions, reinforcing the clock’s dominance.

The game’s systems thus form a clunky but cohesive whole: a timed, keyboard-driven scavenger hunt through a hostile environment, where the joy comes from the quirky nature of the tasks rather than the fluidity of the interaction.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Kitsch is the Message

Visually, Rocky Interactive Horror Show is a product of its constrained timeline and technology. It employs pre-rendered 2D backgrounds with digitized sprite characters. The art direction captures the film’s garish, Gothic-transvestite aesthetic—vivid colors, bizarre costumes, and theatrical sets. While reviewers like David Freeman (TimeWarp) praised the graphics as “detailed and interesting,” others like IGN called them “dated” and “two-dimensional” in an era embracing 2.5D. The FMV sequences, starring O’Brien and Lee, are a double-edged sword: they lend star power and surreal authenticity but suffer from “grainy” compression (GamesReviews2010) and a cheap, intimate feel that some found charming and others found “contrived.”

The sound design is the game’s most unanimously praised element. The CD-ROM doubles as an audio CD, a brilliant feature allowing players to listen to the soundtrack separately. Within the game, the iconic songs are used sparingly—often as leitmotifs in specific rooms (like the Time Warp music triggering during the dance puzzle) or in the in-game jukebox featuring Richard O’Brien’s acoustic performances. The inclusion of three unreleased tracks was a major selling point. The voice acting from Lee and O’Brien is a coup; their serious and mischievous deliveries, respectively, perfectly bookend the experience and are consistently singled out as the audio’s strongest component. However, some sound effects are criticized as “annoying” or “aggravating” (GamesReviews2010), particularly repetitive character noises.

The world itself is the castle, rendered in over 60 locations. It’s a surreal, non-Euclidean funhouse where a freezer houses a biker, a disco room requires dance moves, and a casket contains a decayed body. The atmosphere is one of playful horror and kitsch, successfully translating the film’s tone into spatial puzzles. The setting is the game’s greatest asset, a tangible manifestation of Rocky Horror’s id.

Reception & Legacy: The Cult of the Flawed

Upon release, Rocky Interactive Horror Show received mixed to negative reviews, aggregating to a 57% critic score on MobyGames from four reviews. Positives consistently highlighted: the sheer charm and nostalgia for fans, the successful capture of the film’s campy, surreal humor, the inspired casting of Lee and O’Brien, and the excellent soundtrack/audio package. Negatives were equally consistent: the “clumsy user interface” and keyboard controls, the “outdated visuals,” the “repetitive” and sometimes obtuse puzzles, and the punishing, unfun time limit for non-fans.

- Quandary (70%) admitted enjoying it despite its flaws: “Keyboard control, ticking clock, temperamental interface, I shouldn’t have enjoyed this game at all, but I did.”

- IGN (53%) was dismissive of its game merits: “Singularly non-interactive puzzles, a dated engine, and a plodding pace… Dr. Frank N Furter’s funhouse is anything but kosher.”

- PC Joker (38%) was brutal, calling the puzzles “selten und dröge” (rare and dreary) and the control “arg pingelig” (very finicky).

- Metzomagic framed it as a “novelty with a lot of charm,” enjoyable if one accepts its idiosyncrasies.

Commercially, it was a failure, overshadowed by its own development drama and a market moving decisively away from its design model. Its legacy is that of a deep-cut cult artifact. It is remembered fondly by a small subset of Rocky Horror devotees who appreciate its earnest, if clumsy, attempt to immerse them in the castle. YouTube vlogger PushingUpRoses’ summation that the gameplay is “stupid” but its heart is in the right place is a common fan refrain. It is seen as an improvement over the primitive 1985 text adventure but a missed opportunity compared to what a more modern engine could have achieved. It stands as a cautionary tale about licensed game development: a beloved property is not a substitute for solid design, but the passion of its creator (O’Brien’s heavy involvement) can infuse a technically deficient product with a spark of genuine affection. The 2024 remake by FreakZone (a 2D platformer) underscores how differently the license can be interpreted, leaving this 1999 version as a unique, bizarre historical footnote.

Conclusion: A Time-Warp to a Dead-End

Rocky Interactive Horror Show is a game out of time, in time, and on time. It is a product of delays and corporate death, born into a world that had already left its engine in the rear-view mirror. Its place in video game history is not one of influence or innovation, but of testimony. It testifies to the unwavering—and sometimes commercially unwise—dedication of license holders to adapt their property with creator involvement. It testifies to the messy, transitional period of the late 1990s where CD-ROM extravagance collided with aging adventure game paradigms. And it testifies to the profound truth that a game’s quality is not solely determined by its mechanics, but by the resonance of its world and the sincerity of its tone.

As a game, it is often frustrating, clunky, and politely ignored by the canon of adventure greats. As a Rocky Horror experience, it is a fascinating, if flawed, deep dive into the castle’s nooks, extended by the magnetic presence of its creators. Its 57% aggregate score is a fair mathematical average of these two realities. For the historian, it is an essential study in adaptation challenges and market context. For the fan, it is an obscure, charming, and collectible curio. For the general player, it is a perplexing relic best approached with the same mix of skepticism and open-minded curiosity one might bring to a late-night screening of the film itself. It does not succeed on conventional terms, but in its chaotic ambition to make you feel like you’re in the movie, it achieves a perverse, petrified kind of victory. It is, ultimately, the game equivalent of a well-loved, slightly moth-eaten vintage corset: impractical, uncomfortable for the uninitiated, but for those who get it, utterly indispensable.