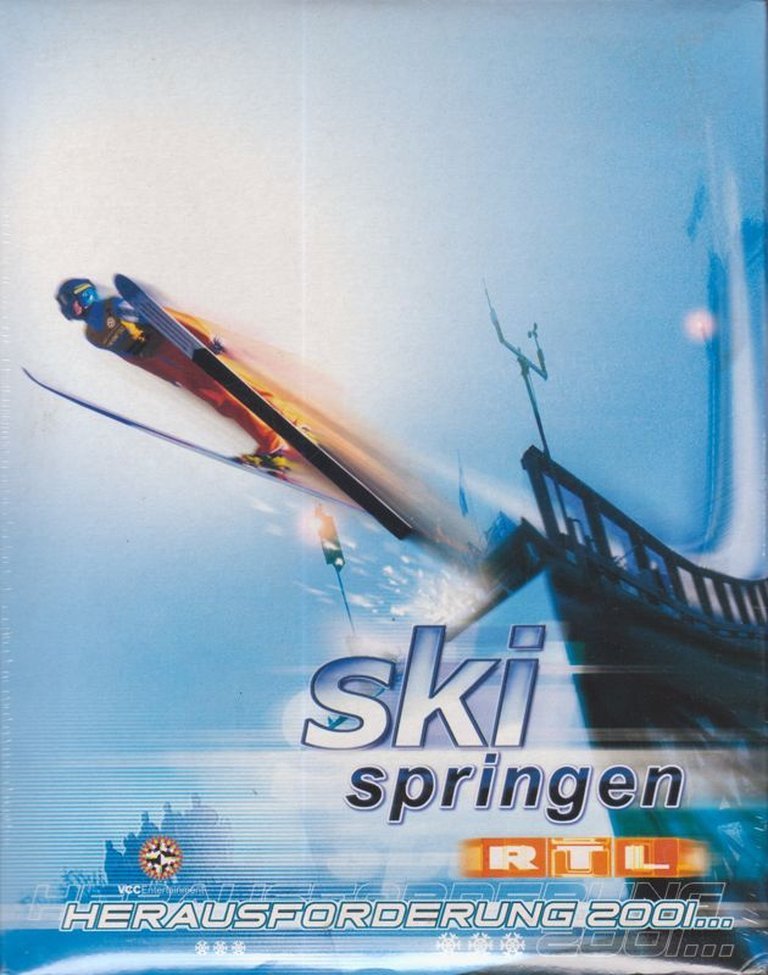

- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Axel Springer Polska Sp. z o.o., VCC Entertainment GmbH & Co. KG

- Developer: VCC Entertainment GmbH & Co. KG

- Genre: Ski jumping, Sports

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Hotseat

- Gameplay: Career mode, Equipment, Management, Training

- Setting: Winter Sports

- Average Score: 67/100

Description

RTL Skispringen Herausforderung 2001 is a licensed ski jumping sports game developed by VCC Entertainment. Players must train and manage their jumper through the 2000/2001 ski jumping season, competing on 16 different jump hills. The game features both World Cup and Four Hills Tournament modes, with up to 72 computer opponents, various weather conditions, and a career mode that includes earning prize money, securing sponsorships, and managing equipment. It also offers hot seat multiplayer for competitive play with friends.

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (66/100): A Skijumping game in license with a german broadcast tv. You have to train and manage your jumper.

kultboy.com (68/100): Ein Spiel für Einsteiger und Profis laut Testbericht der PC Games.

RTL Skispringen Herausforderung 2001: A Deep Dive into a Niche Sporting Relic

As a professional game journalist and historian, I have spent decades unearthing and analyzing the hidden gems and forgotten curios of our medium. Today, we turn our attention to a title that embodies a very specific, almost anachronistic moment in both sports gaming and European PC software: VCC Entertainment’s RTL Skispringen Herausforderung 2001. This is not a review of a blockbuster; it is an archaeological examination of a deeply niche, commercially licensed product that strived for authenticity within severe technological and conceptual constraints. Its legacy is not one of revolution, but of a peculiar, almost charming dedication to a singular sporting pursuit.

Introduction: The Lonely Leap

In the winter of 2000, as the gaming world was being reshaped by the emotional depth of Final Fantasy IX and the sprawling ambitions of Deus Ex, a smaller, colder wind blew from Germany. RTL Skispringen Herausforderung 2001 (literally “RTL Ski Jumping Challenge 2001”) was not here to redefine the medium. It was here to simulate the precise, terrifying, and breathtakingly brief act of hurling oneself off a snow-covered ramp on two skis. Its thesis is one of pure, unadulterated simulation: to capture the tension of the in-run, the critical timing of the take-off, and the aerodynamic ballet of the flight for a dedicated audience of winter sports enthusiasts. It is a game that is, by its very nature, an acquired taste—a five-minute thrill that either becomes instantly repetitive or a compelling loop of self-improvement, largely dependent on the player’s predisposition to its subject matter.

Development History & Context: The Licensed Niche

To understand Herausforderung 2001, one must first understand its creator, VCC Entertainment. This was a studio that operated firmly within a specific Germanic software ecosystem, specializing in licensed, accessible titles often tied to television properties. Their portfolio included games for the action series Alarm für Cobra 11 and, most notably, a series of winter sports simulations. This game was the second entry in their ski jumping series, following a previous iteration and preceding RTL Skispringen 2002.

The game was a product of its time and its business model. The licensing partnership with RTL Enterprises, a major German broadcast network, placed it in a specific context: it was a commercial product designed to capitalize on the televised spectacle of the real-world FIS Ski Jumping World Cup and the prestigious Four Hills Tournament. This was not an artistic vision born in a vacuum; it was a calculated venture aimed at a market that consumed these events on television.

Technologically, the game was developed for the everyman’s PC. Its modest system requirements—an Intel Pentium II, 32 MB of RAM, and a 4 MB VRAM 3D accelerator—place it squarely in the lower-mid tier of hardware for the year 2000. This was not a title pushing the boundaries of the new millennium’s graphics; it was a title ensuring it could run on the family computer. The development team, led by Product Manager Robert Kuehl and Producer Christian Weikert, with key technical work from programmers like Peter Cukierski and engine designer Dierk Ohlerich, worked within these constraints. Their vision was not to create a visual masterpiece but a functional, playable simulation that could deliver the core fantasy of ski jumping to a broad audience with modest hardware.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Drama of the Distance

To speak of “narrative” in RTL Skispringen Herausforderung 2001 is to use the term in its most abstract sporting sense. There is no plot, no characters with dialogue, and no traditional story arc. Instead, the narrative is one emergent from its career mode—a player-driven drama of progression, management, and athletic triumph.

The “characters” are the player’s created jumper and the 72 computer opponents who, as noted by critics like PC Action, lack the names of real-world athletes due to licensing limitations. This absence of authenticity was a noted flaw, stripping away a layer of connection to the real-world sport. The drama, therefore, is not in rivalries with famous jumpers but in the pure, personal challenge of mastering the game’s mechanics.

The themes are those of any sports simulation: discipline, precision, and incremental improvement. The game introduces a management layer where prize money earned from competitions can be invested in better equipment and training regimens. This meta-game provides a strategic narrative thread—the journey from a novice jumper with basic gear to a world-class athlete financed by sponsorships and victories. The underlying theme is one of control: over your athlete’s form, over his career, and ultimately, over the unforgiving physics of the jump itself. The dialogue is the silent, tense conversation between the player and the UI, the frantic adjustments made during the few seconds of flight, and the roar of the (often repetitive) crowd sound effects.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Precision of the Mouse

The core gameplay loop of Herausforderung 2001 is deceptively simple and entirely focused on its singular event. A jump is broken down into three critical phases, primarily controlled via the mouse:

- The In-Run: The skier descends the ramp. Player input here is minimal but crucial, involving adopting an aerodynamic tuck.

- The Take-Off: The moment of truth. As the skier reaches the end of the ramp, the player must click the mouse button with perfect timing to initiate the jump. A fraction of a second too early or too late catastrophically impacts distance and stability. This is where the game’s entire challenge is concentrated.

- The Flight: After take-off, the player must carefully guide the jumper into a stable, aerodynamic V-style position and hold it for the duration of the flight. Wobbling or losing form leads to a shorter jump and poor style marks.

This loop is repeated across 16 different jump hills, modeled after the real-world venues of the 2000/2001 season, including the iconic Four Hills Tournament locations. The management layer surrounds this core action. Between events, players manage their jumper’s training, purchase new skis and suits, and handle finances.

The UI is functional, presenting all necessary data—wind conditions, jump length, style points—without flourish. The hot seat multiplayer mode was a highlighted feature, allowing friends to take turns and compete for the longest jump on the same machine, a social feature that critics like GameStar found to be the game’s greatest strength, transforming a solitary experience into a “much fun” shared competition.

However, the systems are not without flaw. Critics universally panned the lengthy and tedious wait times as the AI opponents take their jumps, a severe pacing issue that disrupts the game’s rhythm. Furthermore, the career mode’s longevity was questioned; the novelty of the jump mechanic, while compelling in short bursts, was seen as potentially too “monotonous” (PC Player) for extended single-player engagement without additional sports or modes to break the repetition.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Sterile Winter

The aesthetic presentation of Herausforderung 2001 is where its budgetary and technological constraints are most glaringly apparent, and where contemporary critics were most harsh.

The world-building is limited to the ski jumps themselves. The 3D landscapes, while featuring varied ramp designs, are sterile and lifeless. As Computer Bild Spiele famously critiqued, the spectators are “unbeweglichen Zuschauer” (immobile spectators) who look like “flache, starre Pappkameraden” (flat, rigid cardboard figures) glued to the stands. There is no sense of a living, breathing world beyond the ramp.

The art direction is purely functional. The character models for the jumpers are rudimentary, with animations that Computer Bild described as “staksen wie tiefgefroren” (stomping around as if deep-frozen). The weather effects—a key advertised feature—are implemented in a “grob und kantig” (coarse and jagged) manner. The game strives for realism but is hamstrung by its technology, resulting in a visual experience that fails to capture the grandeur and atmosphere of its real-world inspiration.

The sound design follows suit. The effects of skis on snow and wind during flight are adequate but unremarkable. The crowd noise, however, was singled out as being repetitive and generic (“der Jubel klingt immer ähnlich”), further diminishing any sense of occasion. The music, composed by Ronny Pries, serves its menu-purpose but does little to elevate the experience. The overall audio-visual package creates a cold, clinical, and ultimately unconvincing arena for its otherwise carefully simulated sport.

Reception & Legacy: A Forgettable Flicker

Upon its release in late 2000, RTL Skispringen Herausforderung 2001 was met with a lukewarm, if understanding, critical reception. With an average critic score of 66% on MobyGames, the consensus was clear: a competent simulation hamstrung by a lack of polish and atmospheric depth.

Publications praised its accessible yet challenging control scheme (PC Games: “So banal das Spielprinzip ist, so sehr fesselt die Weitenjagd”), its motivating career and management options (PC Action), and its value as a multiplayer hot-seat experience (GameStar). However, they universally condemned its dated graphics, lifeless presentation, and repetitive long-term gameplay. It was seen as a marked improvement over its predecessor but still a niche product with limited appeal.

Commercially, it occupied a specific shelf space in German and Polish software stores (under the title Skoki Narciarskie 2001: Polski Zwycięzca), likely finding its audience among dedicated skiing fans but failing to make a dent in the broader market.

Its legacy is microscopic yet distinct. It cemented VCC Entertainment’s reputation as a purveyor of licensed winter sports games, leading to several sequels on more powerful platforms like the PlayStation 2. Within the ultra-niche genre of ski jumping simulations, it is remembered as a stepping stone—a flawed but earnest attempt that proved there was a market for this specific fantasy on home computers. It did not influence the industry at large, but it served its dedicated audience. Today, it exists as a curiosity, a fossil from an era when licensed games could be simple, singular simulations aimed at a specific demographic, untouched by the live-service models and open-world bloat of modern gaming.

Conclusion: A Verdict for the Dedicated

RTL Skispringen Herausforderung 2001 is not a great game by any conventional measure. It is visually dated, acoustically repetitive, and mechanically simplistic. Yet, to dismiss it entirely would be to ignore its purpose. As a piece of historical software, it is a fascinating time capsule of early-2000s European budget game development and the power of television licensing.

Its value lies almost entirely in its purity of focus. It is a game about one thing and one thing only: ski jumping. For a certain player—perhaps a fan of the sport, or someone looking for a simple, competitive hot-seat experience—it provided a few hours of genuine, tense fun. For everyone else, it was a forgettable also-ran.

The final verdict is one of context. As a piece of interactive entertainment for the masses, it earns a thin, qualified “good” as one German critic put it. But as a dedicated simulation for a specific audience, it succeeded on its own modest terms. It is a forgotten footnote, but a footnote that represents an entire ecosystem of gaming that has all but vanished—and for that, it deserves this moment of remembrance.