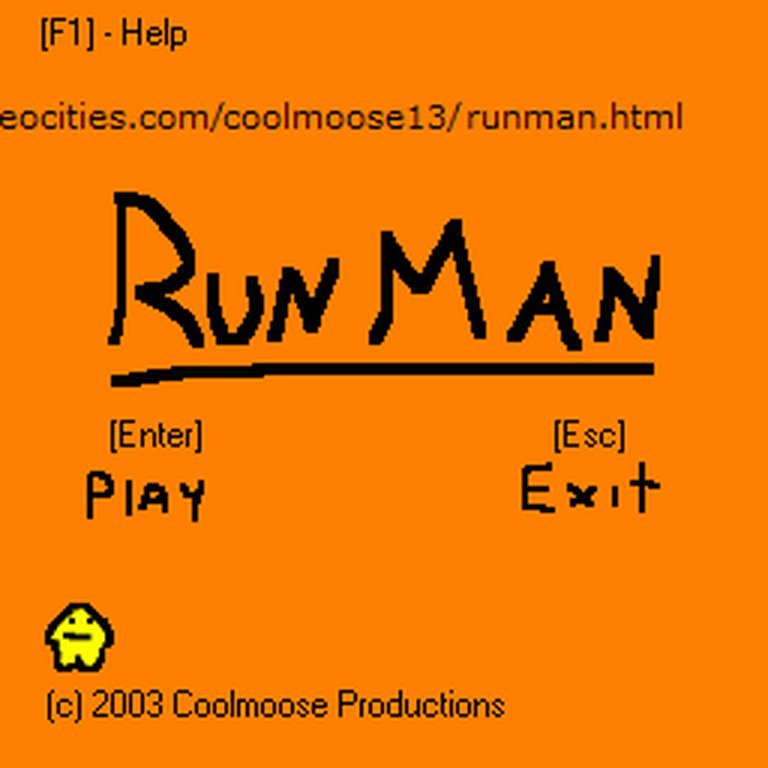

- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Coolmoose Productions

- Developer: Coolmoose Productions

- Genre: Action, Driving, Racing

- Perspective: Third-person, Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Ducking, Endless runner, Jumping

- Average Score: 60/100

Description

RunMan is a straightforward endless runner game set in a dynamic, ever-changing environment where the titular character sprints forward automatically at increasing speeds, challenging players to survive by jumping over obstacles or ducking to roll beneath them. Released in 2003 as freeware for Windows and developed using GameMaker, the game features simple side-view 3rd-person perspective gameplay, incremental speed boosts for successful dodges, visual transitions like day-to-night cycles and rain effects after certain milestones, and a high score list to track player progress in this addictive test of reflexes.

Gameplay Videos

RunMan Free Download

RunMan: Review

Introduction

In the annals of early 2000s indie gaming, few titles evoke the raw thrill of unadulterated speed like RunMan, a deceptively simple endless runner that burst onto the scene in 2003 as a freeware gem crafted on a shoestring budget. Imagine a yellow-haired protagonist dashing forward at escalating velocities, forcing players into split-second decisions between leaping over barriers or ducking beneath them—it’s a formula that predates modern hits like Temple Run or Subway Surfers by nearly a decade, yet it captures the essence of arcade purity in an era dominated by hulking AAA blockbusters. As the foundational entry in Tom Sennett’s beloved RunMan series, this unassuming Windows title not only launched a franchise that would inspire a generation of indie developers but also encapsulated the DIY spirit of GameMaker-fueled creativity. My thesis is straightforward: RunMan may be a minimalist relic of bedroom coding, but its elegant mechanics and infectious momentum cement it as a pioneering artifact in indie gaming history, one whose legacy extends far beyond its modest origins to influence speedrunning, platforming, and the very notion of accessible, joyful escapism.

Development History & Context

The story of RunMan begins in the humble confines of a Windows 95-era family computer, where teenage creator Tom Sennett first tinkered with Mark Overmars’ GameMaker engine—a revolutionary tool that democratized game development for non-programmers in the early 2000s. Released on December 11, 2009, in MobyGames records but actually debuting in 2003, RunMan was a solo endeavor by Sennett under his Coolmoose Productions banner, born from floppy-disk transfers between bedroom and basement machines due to spotty internet access. Sennett, then a self-taught artist drawing with a mouse in MS Paint, envisioned a quick arcade diversion that captured the relentless forward drive of classic side-scrollers like Super Mario Bros. and early Sonic the Hedgehog titles, but stripped to their barest essentials.

The technological constraints of the era profoundly shaped RunMan. GameMaker’s limitations—no built-in physics engines like modern Box2D—meant Sennett had to hand-code every incremental speed boost and obstacle collision, resulting in a lean, performant game that ran smoothly on low-spec PCs. This was the Wild West of indie development: no Steam storefronts, no itch.io, just personal websites and forums like the GameMaker Community where creators like Sennett and future collaborators (such as Maddy Thorson) swapped prototypes. The broader gaming landscape in 2003 was a contrast—Sony’s PlayStation 2 ruled with cinematic epics like Grand Theft Auto: Vice City, while PC gaming leaned toward MMOs like EverQuest. Amid this, RunMan stood as a beacon of freeware accessibility, a public-domain download that anyone could grab without barriers, reflecting the era’s underground ethos where passion trumped profit.

Sennett’s vision evolved iteratively; the original RunMan was a proof-of-concept endless runner, spawning sequels like RunMan Unlimited (2003) and RunMan’s Christmas Adventure (2003), which refined the formula with thematic twists. By 2009, Sennett’s ambitions peaked with RunMan: Race Around the World (RATW), a collaboration with Thorson that transformed the series into a full-fledged platformer. As Sennett later reflected in his “History of RunMan” blog, early games were “short and constrained,” limited by his novice level design skills, but they laid the groundwork for bolder experiments. This progression mirrors the indie scene’s maturation, from forum-shared EXEs to Steam releases, with RunMan as the spark that ignited Sennett’s career and influenced peers like Thorson, whose later works (Super Meat Boy, Celeste) echo the series’ momentum-driven joy.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, RunMan eschews elaborate storytelling for a minimalist parable of perseverance and escalation, a narrative delivered not through cutscenes or dialogue but via kinetic action and environmental cues. The “plot,” if one can call it that, follows the titular RunMan—a slender, fair-skinned everyman with light yellow wavy hair, blue eyes, a blue jacket, white shirt, and a wristwatch—as he auto-runs forward in an abstract, obstacle-strewn world. There’s no voiced exposition or branching paths; instead, the story unfolds as a test of endurance. Starting at a leisurely pace, RunMan surges ahead with each dodged hazard, the speed meter ticking upward like a heartbeat accelerating under pressure. Backdrop shifts—day to night, clear skies to rain—serve as silent milestones, symbolizing the inexorable march of time and mounting challenge.

Thematic depth emerges from this simplicity. RunMan embodies the archetype of the reluctant hero, a “one-man army” thrust into a race against inevitability, much like Sisyphus reimagined as an anthropomorphic speed demon. Sources like the Heroes Wiki highlight his abilities: superhuman running speed (hold the start button for boosts), yet vulnerabilities like low jump height that punish missteps, forcing adaptive techniques like “dash jumping” to recover from spikes or pits. In sequels, this evolves—RATW adds a explicit narrative where RunMan enters a global race, only for competitors to forfeit, prompting him to solo the journey in pursuit of true victory. Dialogue is sparse but punchy: cutscenes in RATW feature whimsical banter, such as RunMan’s annoyed vow to “race around the world by myself,” underscoring themes of self-reliance and anti-trophy hunting.

Underlying motifs draw from Sennett’s indie ethos. The series critiques “difficulty bloat”—unfair checkpoints, lives systems—that gatekeeps fun, promoting instead a welcoming world where failure (like bottomless pits that harmlessly eject you) is a slap on the wrist. Themes of subversion abound: water levels are breezy swims rather than drowning nightmares, lava bounces like trampolines. RunMan’s “sophisticated jerk” persona—cocky yet honorable—reflects the joy of mastery without elitism. In RunMan’s Monster Fracas (2006), he outpaces devouring beasts; in Going Coconuts (2004), tropical perils test resolve. Collectively, the narrative arc across the series is one of growth: from anonymous runner to global icon, mirroring Sennett’s own journey and the indie’s rise from obscurity to cultural touchstone. It’s a tale less about plot twists and more about the thrill of forward motion, where every obstacle dodged whispers, “Keep going—you’re faster than you think.”

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

RunMan‘s core loop is a masterclass in elegant minimalism, boiling platforming down to auto-forward movement, timed jumps (up arrow), and ducks/rolls (down arrow), all controlled via keyboard on a single-player setup. The genius lies in escalation: each successful evasion increments speed, turning a casual jog into a blur of reflexes. Obstacles vary—low barriers demand rolls, high ones jumps—while the top-left speed counter builds tension, encouraging risk for higher scores. High-score lists add replayability, but flaws emerge in its unforgiving ramp-up; at max velocity, pixel-perfect timing feels punitive without tutorials, alienating newcomers despite the freeware model.

Progression is score-based, with no traditional levels in the original—instead, environmental phases (e.g., rain-slicked nights) introduce procedural variety, preventing monotony. Combat is absent; “enemies” are environmental hazards, “defeated” by evasion, though sequels like Monster Fracas add overtaking mechanics where flowers launch you airborne to dodge pursuers. RATW expands this innovatively: 35+ levels across five zones emphasize momentum, with wall-bounces, hang gliders, and unlockable characters like the mighty glacier Stumblor (who tramples foes but struggles with acceleration). The momentum meter multiplies scores at checkpoints when maxed, rewarding flow-state runs over button-mashing.

UI is spartan—speed display, score, and backdrops suffice, with no overwrought HUDs cluttering the side-view perspective. Innovations shine in accessibility: death restarts levels leniently (no insta-kills except manual restarts), subverting Sonic-like frustration for “idealized” speed. Flaws persist in controls—low jump height risks spike adjacency delays—and the original’s endless nature lacks goals, feeling aimless post-novelty. Yet, systems like RATW‘s procedural replayability (levels shift on reruns for medal hunting) and public-domain jazz soundtrack integration elevate it. Overall, RunMan deconstructs platformers into pure rhythm, influencing endless runners while flawed code (clunky from four-year RATW dev) reminds us of indie’s raw edges.

World-Building, Art & Sound

RunMan‘s world is an abstract dreamscape of perpetual motion, a side-scrolling void where grassy fields yield to stormy nights without explicit lore, yet brimming with implied vibrancy. The original’s setting is minimalist: a linear path dotted with geometric obstacles, evolving backdrops that evoke a journey from dawn to dusk, rain adding peril without narrative weight. Sequels flesh this out—RATW spans global biomes (jungles, oceans, volcanoes) subverted for whimsy: nonthreatening water you sprint through, pits that comically respawn you. Atmosphere builds through speed; slow starts lull, frantic peaks immerse, creating a “chill world 1” vibe akin to Super Mario 64‘s Bob-omb Battlefield, where exploration feels freeing rather than foreboding.

Visually, Sennett’s hand-drawn style—low-fidelity, charming doodles in Photoshop with a Wacom tablet—defines the aesthetic. RunMan’s expressive face on every element (obstacles get eyes!) infuses personality; colors pop boldly, separated by black outlines to avoid muddiness on era monitors. No transparency fades—instead, scaling preserves punchiness. Comparisons to Yoshi’s Island flatter: both evoke crayon whimsy without direct mimicry, RunMan‘s palette less textured but uniquely cohesive, like an “idea” of vibrant platformers. Enemies and environs (coconuts in Going Coconuts, monsters in Fracas) anthropomorphize hazards, blending humor with tension.

Sound design amplifies the rush: no original score details survive, but the series leans on public-domain jazz and blues for RATW—Duke Ellington’s “East St. Louis Toodle-Oo” jazzed for jungle maps, evoking 1920s swing to match the speedy groove. SFX are punchy—boings for bounces, whooshes for dashes—while escalating speed warps audio into a symphony of urgency. These elements coalesce into an experience of joyful propulsion: visuals charm with innocence, sound propels with rhythm, world-building invites endless discovery in simplicity. It’s not epic scope but intimate flow that lingers, turning a blank canvas into a canvas of velocity.

Reception & Legacy

Upon 2003 release, RunMan flew under mainstream radar as freeware, garnering niche praise in GameMaker forums but scant formal coverage—mirroring the era’s fragmented indie distribution. MobyGames logs a solitary critic score of 60% from GameHippo.com (2005), calling it a “fine way to kill a little time,” while player ratings average a lukewarm 2.2/5 from one vote, critiquing its brevity. Commercial success was nil—public domain meant zero sales—but downloads proliferated via Sennett’s site, fostering a cult following. Sequels amplified this: RATW (2009) earned raves in indie circles, with Destructoid’s 2009 interview hailing it as “one of the best platformers… indie or no,” praising its Sonic-like flow minus pitfalls. Donations trickled in, funding plushie dreams (unrealized), but the real win was virality—RunMan guest-starred in Super Meat Boy (2010), cementing series status.

Reputation evolved profoundly. Initially dismissed as arcade fluff, RunMan gained retrospective acclaim as indie progenitor; Sennett’s 2024 Steam re-release of RATW (15th anniversary) sparked nostalgia on Reddit and Twitter, with fans crediting it for inspiring their dev journeys. Influence ripples wide: Thorson’s RATW contributions birthed masocore precision in Celeste, while the series’ accessible speedrunning (medals, secrets in RunMan the Great, 2015 mobile port) prefigured Geometry Dash and Bit.Trip Runner. Broader impact? It humanized indies—Sennett and Thorson as “generous, awesome guys” via donationware—paving for itch.io/Steam eras. Flaws like code messiness (admitted in interviews) highlight growth, but legacy endures: RunMan Turbo (upcoming 2023/2024) promises procedural zones, proving the yellow speedster’s timeless sprint through gaming history.

Conclusion

RunMan endures not as a flawless masterpiece but as a foundational sprint in indie evolution—a 2003 spark that ignited a series blending arcade simplicity with profound joy, from endless dodges to globe-trotting bounces. Its mechanics innovate accessibility amid constraints, visuals and sound craft whimsical momentum, and themes champion perseverance without punishment, all while influencing a wave of speed-centric indies. Though reception started modest, its legacy as a GameMaker trailblazer and inspiration for creators like Thorson solidifies its place: essential for platformer historians, a delightful relic for retro enthusiasts. Verdict: 8/10—timeless fun that reminds us why we run toward the next horizon. If you’re yet to dodge an obstacle, download it free; the rush awaits.