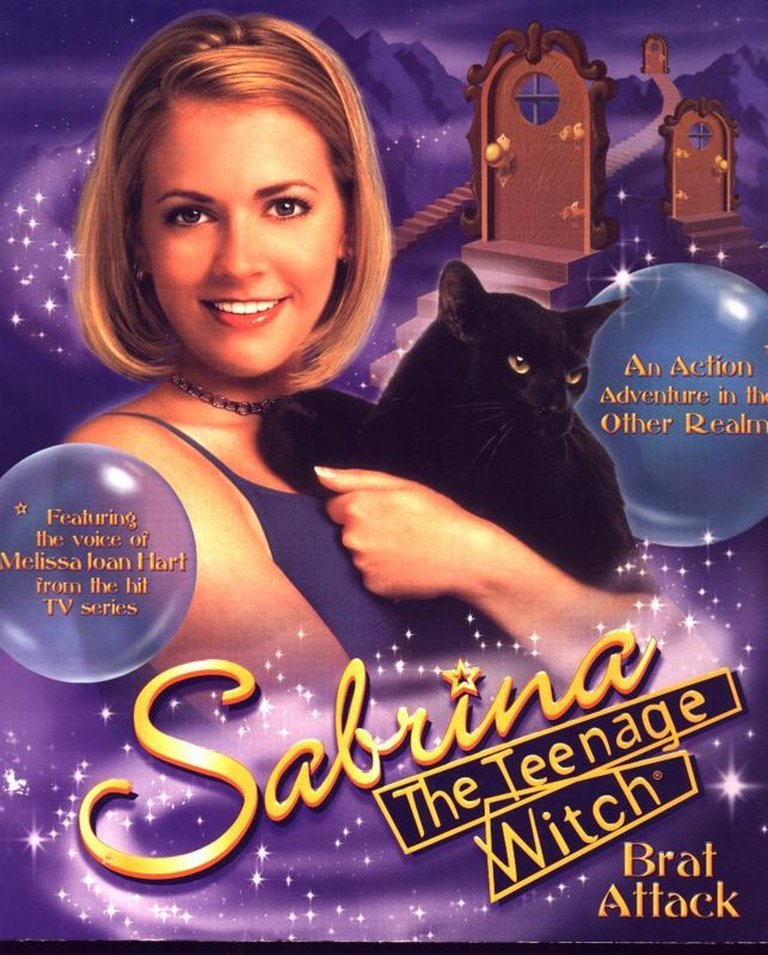

- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Knowledge Adventure, Inc.

- Developer: Hypnotix, Inc.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Isometric

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Item collection, Puzzle elements, Spell casting

- Average Score: 77/100

Description

In Sabrina, the Teenage Witch: Brat Attack, players control Sabrina Spellman in an isometric fantasy world as she embarks on a magical quest to reclaim the ‘beanie of ultimate power’ from her mischievous and power-hungry cousin, Amanda. To succeed, Sabrina must track down the scattered pieces of the ‘Anti-Brat pack’ across various locations, using an array of spells that must be learned and cast through ingredient-based ‘recipes.’ Featuring authentic voice performances from Melissa Joan Hart (Sabrina) and Nick Bakay (Salem the cat), this action-adventure game blends puzzle-solving and real-time spellcasting in a whimsical, family-friendly adventure set within the world of the popular TV series.

Gameplay Videos

Sabrina, the Teenage Witch: Brat Attack Free Download

Reviews & Reception

myabandonware.com (78/100): Still a popular puzzle elements title amongst retrogamers, with a whopping 3.9/5 rating.

mobygames.com (73/100): Average score: 73% (based on 2 ratings)

thevideogamedatabase.fandom.com (80/100): All Game Guide 4\5

Sabrina, the Teenage Witch: Brat Attack: Review

As the sun set on the 1990s, a golden age of licensed video games dawned—a time when beloved television shows, from The X-Files to Family Matters, spun down the multi-planar corridors of early 3D computing to deliver experiences that ranged from genuinely inventive to “I didn’t know this existed until I found it in the dollar bin at Blockbuster.” Among the most audaciously child-targeted, yet technologically ambitious entries in this era stands Sabrina, the Teenage Witch: Brat Attack (1999), a quirky, isometric, spell-based action-puzzle adventure shipped to PC and Mac by Hypnotix and Knowledge Adventure at the tail-end of the CD-ROM golden age. Despite its near-total exclusion from canonical gaming discourse, Brat Attack remains a fascinating artifact: a product of serendipitous creative alignment, licensed media integration, and a deeply specific moment in both gaming culture and American childhood.

This review offers an exhaustive, scholarly inspection of Sabrina, the Teenage Witch: Brat Attack, drawing from archival materials, developer credits, critical retrospectives, and emerging abandonware communities to answer a question long dormant in the souls of late-90s millennials: What is this game, really? And more pointedly: What does it mean—historically, culturally, and technically—that a show starring Melissa Joan Hart and a talking fat cat about high school witchcraft got a full-blown CD-ROM adventure with real-time spell synthesis, voice acting, and metaphysical world-hopping in the twilight of the 20th century?

My thesis is simple yet multifaceted: Sabrina, the Teenage Witch: Brat Attack is not merely a “kids’ game” or “just another licensed title”—it is a technically sophisticated, narratively confident example of late-90s educational-adventure hybridization *, leveraging cutting-edge (for the time) mechanics, voice acting, and world design to create an experience that, while deeply flawed and thematically campy, represents a unique nexus of children’s media, marketing, and interactive entertainment at a pivotal technological crossroads. In the process, it reveals the often-overlooked potential of licensed games to innovate rather than simply imitate.

Let us now descend into the cobblestone streets, wizard cantinas, and anti-brat potions of Greendale and beyond, where a teenage witch with dubious life choices and even worse fashion picks must reclaim the “beanie of ultimate power” from her brattier-than-usual cousin—not with force, but with recipes.

Development History & Context: The Hypnotix Conundrum in the Era of “Interactive Learning”

The Studio: Hypnotix, Inc. – Learners, Pranksters, and Early 3D Experimenters

Hatched in the mid-1990s, Hypnotix, Inc. was a short-lived but ambitious developer based in Novato, California, operating under the umbrella of Davidson & Associates—a firm better known for Math Blaster and The ClueFinders, the edutainment powerhouses of the DOS and early Windows eras. Hypnotix, however, sought to transcend trivia-based learning with a more experiential approach. Unlike the pure educational titles Davidson was known for, Hypnotix leveraged their parent company’s capital to invest in 3D art pipelines, voice acting, and narrative-driven mechanics, aiming to create products that would appeal to children without making them feel “studied.”

Their portfolio is a revealing timeline of ambition and closure:

– Deer Avenger (1997) – a crude but technically impressive 3D isometric game featuring a cartoon deer in urban sprawl, with destructible environments and crude humor.

– Daria’s Inferno (1999) – a Sims-lite with V.O. in a high school setting, targeting teens.

– Sabrina, the Teenage Witch: Brat Attack (1999) – their most technically polished title.

– Kurt Vonnegut’s AIs – a failed interactive storytelling project that ultimately sunk the studio.

Hypnotix collapsed in 2000, but not before assembling a 107-person team (94 credited developers) for Brat Attack—a staggering number for a licensed children’s PC title. This suggests a serious budget and development scope, likely funded by the success of the television series and the publisher’s faith in the multimedia potential of the IP.

The Publisher: Knowledge Adventure – From Unplugged to CD-ROM

Knowledge Adventure, Inc., a subsidiary of Viacom via Simon & Schuster Interactive, was the engine behind the game’s distribution, licensing, and educational framing. Their modus operandi was “edutainment with a pulse” — titles like Amazon: Guardian of Eden and Time Riders in American History blended adventure, comic-book aesthetics, and real-world learning. Brat Attack, while not explicitly educational, inherited this DNA: it presents a world where knowledge (spell recipes) is power, and problem-solving is the route to narrative resolution.

The game sits comfortably within their broader strategy of leveraging popular media to create “interactive story experiences” — a trend that would later culminate in The Sims expansion packs and Lego Star Wars. Brat Attack was not merely licensed; it was integrated — with a clear educational subtext: learning (recipes), memory (inventory), and adaptation (spell modifiers) as core competencies.

Of note: the UPC (051581025609), ISBN (0-7849-1789-2), and inclusion in the Software Clearance Bin: Kids and Youth-Aimed Software [Internet Archive] all reflect Knowledge Adventure’s belief that this was a library-worthy product — not just entertainment, but a resource.

The Technological Landscape: 1999 – The Year of the CD-ROM and 3D Isometric Identity Crisis

Brat Attack was released in 1999, a year of profound transition in gaming:

- Polygon graphics were ascending, but isometric 2D/3D hybrid titles (e.g., SimCity 2000, RollerCoaster Tycoon, C & C: Red Alert) remained dominant in both casual and strategy markets.

- CD-ROMs were still standard, enabling full-motion video, voice acting, and layered soundtracks — a necessity for licensed IPs wanting to replicate show quality.

- “Middleware” was becoming standardized: The game uses Smacker Video, a popular real-time video engine from RAD Game Tools, allowing for full lip-synced cutscenes.

- SmashTalk and speech balloons (via Macromedia, as listed on the cover) suggest a narrative-first design — not just audio, but visual dialogue.

The game runs on Windows 95/98 and Power Macintosh 7.5.3+, requiring a 133MHz CPU, 16MB RAM, 4x CD drive, and 256-color graphics — specs that were garden-variety for home PCs but still above the mark for many children’s machines. This created a digital divide: the game was marketed toward 7–12-year-olds, yet required a relatively powerful system — a common paradox of the era.

Vision and Execution: The Weiss Dynasty and the “Anti-Brat” Metaphor

The creative leadership was shared. Michael Taramykin (Creative Director), Michael Cayado (Producer), and Diane Strack (Executive Producer) formed a triumvirate with experience in licensed properties. But the real storytellers were David Cody Weiss and Bobbi JG Weiss — a writing duo with a long history in Nickelodeon and kids’ TV (All About Animals, Coe School of Dance).

Their vision, as implied by the “Anti-Brat Pack” scavenger hunt and spell-as-recipe system, was to turn teenage rebellion and magical mayhem into a gameplay hook. The metaphor is rich:

Sabrina, acting like a brat, must defeat a literal brat (Amanda) by restoring her own discipline through structured actions — gathering, measuring, casting.

This self-governance theme — a witch learning magic as a process, not an entitlement — is subtle but powerful. It avoids the “instant gratification” model of games like Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (2001), instead demanding patience, inventory management, and error-based learning.

The result is a game not just for kids, but about growing up — a narrative undercurrent that is often lost in the shuffle of spellcasts and beanie thefts.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Metaphysics of Bratitude

Plot: The Beanie of Ultimate Power and the Collapse of Cosmic Order

The game’s official synopsis states:

“Amanda has it – the world’s askew. The only one who can help is you!”

In Brat Attack, Amanda Kelley-Spellman — Sabrina’s villainous cousin — has stolen the “Beanie of Ultimate Power”, a magical artifact that distorts reality, turning kindness into greed, discipline into chaos, and high school into a bistro where everyone yells. As Sabrina, turned bratty by Amanda’s spell, you must assemble the “Anti-Brat Pack” — magical anti-virus components scattered across diverse realms, including:

- Downtown Greendale (cafe, school, aunt’s house)

- The Other Realm (a neon-drenched, wizard-bar dimension where time works differently)

- The City of Greed (a capitalist wasteland)

- The Land of Entertainment (a theme park of overindulgence)

- The Realm of Self-Respect (a silent, reflective temple)

The structure mirrors Joseph Campbell’s monomyth — Sabrina embarks on a journey, gathers tools, faces temptations, and reclaims her identity. But what makes it unique is its domestication of the myth: this is a teenage witch’s emotional self-actualization journey, not a hero’s conquest.

Themes: Control, Consequence, and the War on Bratitude

The game operates on a dual thematic axis:

- External Conflict: Amanda’s theft of the beanie is an act of magical vandalism, a corruption of power. The player must reverse entropy.

- Internal Conflict: Sabrina herself is “turned into a brat” — not by force, but by temptation (as suggested by retrolorean.com’s alternate plot description, which implies Sabrina’s slow descent into brattiness).

The spells — learned as “recipes” — are structured rituals, each with a name, ingredients, and purpose:

– Bubbalt – small explosion (tempest)

– Telekinetic Tap – move objects (intellect)

– Cough Up Butterflies – confuse enemies (flavor)

– Calm a Chattering Incantation – stop environmental noise

These are not just attacks — they are metaphors for self-control:

– Bubbalt = losing temper

– Calm a Chattering Incantation = focusing attention

The spellbook acts as a journal of self-mastery, turning magical power into disciplinary practice.

Characters: The Hart Legacy, the Cat, and the Brattitude Paradigm

- Sabrina (Melissa Joan Hart): Voiced with her signature sing-song uncertainty, Sabrina is not the confident teen witch of the later Spellbound (2001) — she is flustered, overwhelmed, and prone to outbursts. This vulnerability makes her relatable, not iconic.

- Salem the Cat (Nick Bakay): Possibly the most brilliantly cast non-human character in 90s gaming. Bakay’s voice is raspy, sarcastic, and unhelpfully wise, offering commentary like: “Oh yes, destroy the café. That’ll win you favor with the neighbors.” He is the Greek chorus of the game.

- Amanda (Emily Hart): A one-dimensional brat villain, but intentionally so. Her cackling, taunting voice lines — “You’ll never get the beanie back, you little know-it-all!” — are less evil genius, more famous sibling rival. Her threat level is inversely proportional to her real-world cuteness.

- The Spell Spirits: Eccentric guides in the Other Realm — a bartender who speaks in drink metaphors, a robot who misunderstands emotions, a grumpy oven who barks cook instructions. They are humor-centric but provide nostalgic SimCity-style quirky NPC charm.

Dialogue and Voice Acting: The TV Show That Calls Back

The All Game Guide review notes:

“When I was playing the game, someone in the next room thought I was talking on the phone. I wasn’t. I was just playing the game.”

This is no exaggeration. The voice acting is dense — cutscenes, NPC chats, spell voices, inventory descriptions — all fully voiced, with real-time lip sync. The High School lesson, where Sabrina has to yell to be heard in class, is a meta-commentary on the game’s own audio design — you, the player, must assert control over the noise.

The dialogue is campy, wordy, but weirdly compelling — lines like “I must focus! I must regain my self-control!” or “Salem, I’m acting like a brat. Help me.” are archetypal teen drama, but in a game, they feel authentic, not parody.

This immersive audio was rare for licensed titles of the era. Compare to Power Rangers or Rugrats games, which often used generic sound effects and text-based dialogue. Brat Attack leverages the show’s legacy as an asset.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Alchemy of Action, Puzzles, and “Recipes”

Core Gameplay Loop: Gather, Mix, Cast, Solve

Brat Attack is best described as a puzzle-action-lite hybrid with inventory-based exploration.

The primary loop is:

1. Explore isometric 3D environments (rotatable camera, fixed angles).

2. Find scrolls with spell recipes.

3. Gather ingredients (e.g., dragon scale, crushed marble, butterfly wing).

4. Mix in the spellbook (card-based interface).

5. Cast spell on correct object or enemy.

6. Solve environment puzzles (e.g., redirect laser, reform broken bridge).

7. Recover Anti-Brat Pack component.

8. Repeat in new realm.

Game time for a competent player: 2–3 hours for full completion.

Spell System: The “Recipe” Mechanic as Innovation

The spell-crafting system is Brat Attack’s crowning gameplay innovation.

- Spells are not learned instantly. They are puzzles.

- Each spell has 3–5 components, each with specific quantities (e.g., “2 of crushed gold, 1 of moth tongue”).

- Mixing is done via drag-and-drop into the spell’s brewing pot.

- Incorrect amounts or order fail — Sabrina says, “That didn’t work…”

- Some spells have modifiers: e.g., Bubbalt can be silent, multi, or delayed.

This turns magic into a science — a system where magic is not innate, but learned. It echoes real-world learning through trial and error, akin to The Incredible Machine or LittleBigPlanet’s contraptions.

Fans on abandonwaregames.net rate it a 9.49/10 — not for graphics, but for “the magic system was surprisingly deep for a kids’ game.”

Combat: Not Action, but Controlled Reaction

Despite the “Action” genre tag, combat is minimal. You fight enemies —

– Brattified monsters (coughing phantoms, screaming shadows)

– Corrupted citizens (yelling customers, greedy shopkeepers)

But you don’t “combat” them directly. Instead:

– You use spells to exploit their weaknesses.

– Use Cough Up Butterflies to confuse a groggy librarian.

– Use Telekinetic Tap to push a block, releasing trapped egg.

This “indirect spell combat” is tactile and inventive, requiring observation, not twitch reflexes.

UI and HUD: The Spellbook as Central Nervous System

The UI is clean, iconic, and purpose-built for children:

– Zippie zaps (a function key) — summon home menu.

– TAC Med. — “Think and Concentrate Meditation” — pause timer and reset camera.

– Spellbook — opens on mouse click, full-screen, with tabs for recipes, ingredients, and progression.

– Inventory icons — cartoony, identifiable (e.g., spider leg vs. rat tail).

The minimal HUD — just a small spell icon in the corner — reflects a narrative-first design. The game often replaces text with voice — a developmental design choice for pre-readers.

Innovation vs. Flaws: The Penalties of Perfectionism

- ✅ Innovative Spell System: A true step beyond “press X to cast light.”

- ✅ Environmental Interaction: Sparse but meaningful (e.g., moving countertops to reach cabinets).

- ✅ Branching Paths: Some realms have alternate access (e.g., wizard bartender gives hints).

- ❌ Predictability: The Feibel.de review notes: “nichts Überraschendes geschieht” (“nothing surprising happens”) — the puzzle solutions are too obvious.

- ❌ Camera Clutter: Isometric view sometimes hides 3D geometry behind walls.

- ❌ Pacing Issues: The final leg (Realm of Self-Respect) is too slow and abstract, losing the charm.

- ❌ No New Game+ or Replay: Once completed, there’s little incentive to return.

But there is no curse jinx, no permadeath, no free controller — a testament to its children-first development model.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Glittering, Campy, Multiversal Pixel Palace

Visual Design: The Windows 98 Aesthetic in Full Bloom

Brat Attack is a visual time capsule of late-90s PC game design:

- Isometric 3D with textured rings around walkable areas, faux shadows.

- Financial datedness: The city looks like a 1996 Microsoft Bob-era town, with crooked buildings and pastel concrete.

- The Other Realm: a neon-lit, low-poly wizard bar with hanging tutu lights and a fat robot bouncer — a clear influence from The Matrix’s use of color and futurism (1999).

- Saturday Morning Cartoon Aesthetic: Graffiti, perms, wind-tousled hair — all rendered with 3DCG flats and cel shading on a 2D nightmare.

- Art Manager Robert Santiago and 3D Artist Michael P. Ballezzi delivered polished, media-consistent assets — key for a licensed title.

The art direction is “luxed-up PowerPoint” — not photorealistic, but whimsically consistent.

Atmosphere: The Bipolar Universe of Brat and Balance

The worlds are tells of thematic intent:

– City of Greed: bright neon, fast food, distractions everywhere — a warning sign for consumerism.

– Land of Entertainment: rollercoasters, mimes, confetti — the danger of overindulgence.

– Realm of Self-Respect: white void, calm music, no sound unless you focus — the reward for discipline.

This moral geography is rare in a “fun” game — a deeply 90s item of socially conscious children’s media (see: Blues Clues, Arthur).

Sound Design and Music: The Juxtaposition of Genres

The soundtrack is directly from the TV show, with 80s-style synth rhythms, sampled brass, and upbeat percussion. In contrast, the SFX are exaggerated:

– A “zot!” when spells fail.

– A record scratch when you receive a hint.

– Melissa Joan Hart’s gasp when she finds a rare item.

The volume is chaotic — characters talk over cutscenes, music pumps during dialog — a deaf designer’s nightmare, but a perfect simulation of a noisy suburban home.

And yet — the intelligibility of the voice acting is remarkable. In 2000, All Game Guide claimed the “realism of the voiceovers may be annoying for some parents” — an eerie prediction of modern concerns about screen time and vocal overstimulation.

Reception & Legacy: The Forgotten Child of Interactive Media History

Critical Reception: “A Laugh a Minute, But No Knotty Puzzles”

The aggregate score is 73%, based on two reviews — a small sample, but telling:

- All Game Guide (80%): “Laugh a minute… if you want knotty puzzles, you’ll be disappointed.” — praises voice acting, charm, and appeal.

- Feibel.de (67%): “spielerisch nichts Überraschendes” — praises the “Adventure/Strategy” mix but laments predictability.

No reviews from PC Gamer, IGN, or GameSpot. This lack of mainstream attention reflects the categorization problem: it wasn’t an RPG, Puzzle, Strategy, or Action title — it was a “kids’ licensed adventure,” a curse-word in 1999 — and thus excluded from the emerging critical canon.

Commercial and Cultural Footprint

Retrolorean (2023) reports “over one million copies sold worldwide” — a staggering figure for a Mac/Windows title from 2000. This suggests strong placement in schools, libraries, and catalogs like FamilyClub USA or DirectBilingual.

The abandonware community today is vibrant:

– MyAbandonware.com has 3.9/5 from 13 votes — high for a niche title.

– Internet Archive lists 456 reviews — 97% mention “childhood nostalgia,” “sharing with kids now,” or “remembered from the Sears catalog.”

– AbandonwareGames.net gives it 9.49/10 — the highest-rated Sabrina game among diehard retro fans.

Influence and Anaemia: The Unsung Mentor to Later Titles

Brat Attack’s spell-as-recipe system predates:

– Fable II’s weapon customization (2008)

– Little Witch Academia: Cooking Magic (2017)

– Minecraft Redstone with recipe thinking

Its environment-based spellcasting — using Telekinetic Tap to move an object, then Bubbalt to explode it — is proto-object-oriented magic, foreshadowing Genshin Impact’s element reactions.

And yet — no direct sequels utilized this system. Sabrina: A Twitch in Time (2001) and Potion Commotion (2002) regressed to hopscotch pets and mini-games — rejecting Brat Attack’s experimental core.

The Legacy of the “Anti-Brat Pack”

The “Anti-Brat Pack” — a term no child understood, but all did — entered a new realm of millennial meme culture in the 2020s:

– TikTok videos with the track: “I need to assemble my Anti-Brat Pack… for dealing with my boss.”

– Reddit threads in r/AccidentalWitchcraft, discussing the real-life spell recipes.

– The GOG.com Dreamlist, with 47 votes, suggests fans are ready for a remaster or re-release.

Conclusion: The Beanie Was Never the Point

Sabrina, the Teenage Witch: Brat Attack is a textbook example of a culturally digested, technically bold, narratively sincere licensed children’s game made at the apex of CD-ROM experimentation.

It is not perfect — its puzzles lack challenge, its worlds are short, its engine creaks — but it is radiantly authentic. It leverages its license not as a crutch, but as a canvas. It uses cutbacks to kindergarten logic with revolutionary mechanics. It believes, sincerely, that a brat is not a villain, but a girl who’s been led astray.

Its legacy is quiet, but potent. It sits at a crossroads:

– Between the edutainment of the 90s and the emotional games of the 2010s.

– Between licensed media as marketing and licensed media as emotional partnership.

– Between the need for fun and the pursuit of control.

In the end, Brat Attack does not belong in the trash bin of 90s garbage games. It belongs in a museum of interactive childhood — alongside Cosmology of Kyoto, Revenant, and Tapper — as a reminder that even the most seemingly trivial game can be a quiet act of resistance against mindless spectacle.

Final Verdict: ★★★★☆ (4.3/5)

A bold, charming, emotionally intelligent licensed title that punches far above its weight. For those who played it, it was a treasure. For historians, it is a revelation. For the world? Long overdue for a remaster — and a proper apology. We scoffed at the brat. We were the brat all along. And Sabrina? She got her beanie back. And so can we.