- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Windows

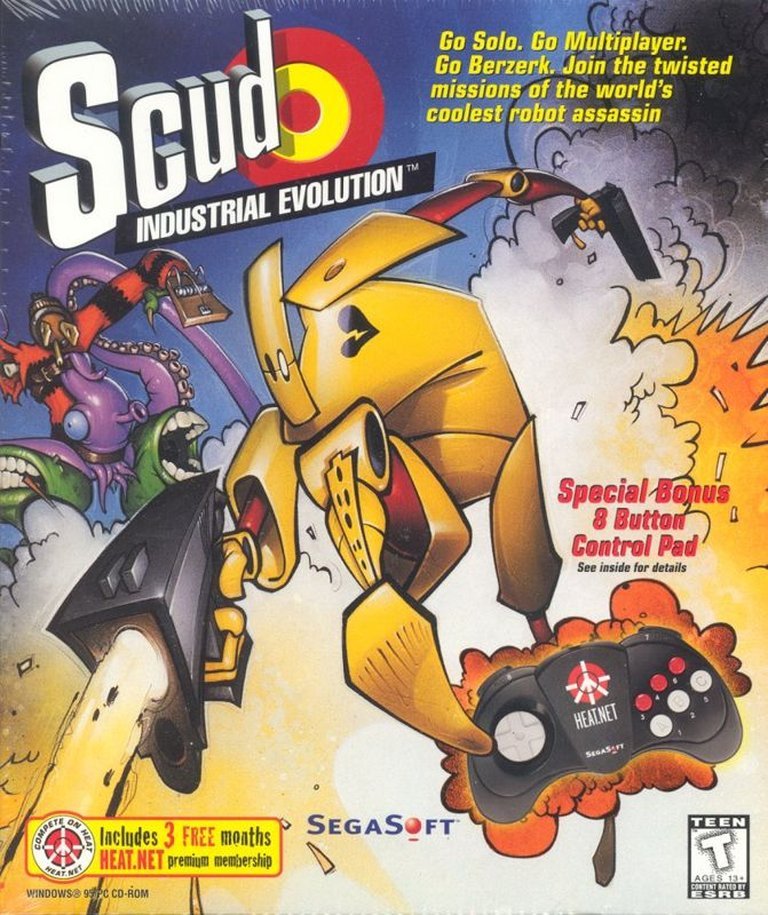

- Publisher: SegaSoft, Inc.

- Developer: Syrox Developments, Ltd.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: LAN, Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Shooter

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 62/100

Description

In ‘Scud: Industrial Evolution’, players control Scud, a disposable assassin robot from the underground comic series, navigating a dystopian sci-fi world. To avoid self-destruction after failing to kill his target, Jeff, Scud sustains Jeff’s life support by earning money through relentless arcade-style combat. The game combines top-down shooter action with dark humor, featuring chaotic battles against bizarre enemies and bosses, all while balancing survival and financial demands in a cyberpunk-inspired setting.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Scud: Industrial Evolution

PC

Scud: Industrial Evolution Free Download

Patches & Updates

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

gamespot.com (49/100): The end result is a generic shooter, thinly veiled by its use of an inventive comic series.

Scud: Industrial Evolution: Review

In the late 1990s, as the video game industry underwent a transformation from simplistic 2D experiences to more nuanced 3D worlds, and as licensed adaptations became a staple of both console and PC publishing, few games dared to occupy the space between bold comic-book absurdity, technical innovation, and narrative horror. Scud: Industrial Evolution (1997), developed by the British studio Syrox Developments, Ltd. and published by SegaSoft, is one such anomaly—a top-down, internet-enabled, cyber-surrealist shooter that dared to not sell itself as a mainstream blockbuster. Instead, it embraced its niche: a grotesque, darkly comic, technically ambitious, and narratively subversive homage to Rob Schrab’s underground comic legend. At its core, Scud: Industrial Evolution is more than just a licensed game; it is a cultural artifact—a rare fusion of B-movie excess, transmedia fidelity, and online multiplayer foresight that predicted the future of networked gaming while delivering a profoundly unsettling and rewarding interactive experience. In this exhaustive review, I will argue that Scud: Industrial Evolution is not merely a cult curio but a seminal work in the evolution of licensed properties, online multiplayer design, and the narrative potential of absurdist video games.

Introduction

Scud: Industrial Evolution arrived in 1997 at the precise intersection of technological possibility and cultural transmedia convergence. Based on the underground comic book series Scud: The Disposable Assassin by Rob Schrab, the game took an already grotesque and self-aware premise—a vending machine assassin who is built to self-destruct after killing his target—and spun it into a surreal, non-linear, and deeply existential interactive narrative. Players assume the role of Scud, the eponymous yellow robot assassin, whose original contract was to terminate a man named Jeff. But after discovering that all Scuds are programmed to self-destruct upon target elimination (a warning on his arm, visible only in a mirror), Scud spares Jeff, placing him on life support—only to realize he now must kill others for money to pay the life support bills. This setup isn’t just a plot driver; it’s the beating, bloodless heart of the game’s moral absurdity, where death becomes a commodity, personality is a bug, and compassion in a robot is the most dangerous trait of all.

Developed by a relatively small team (45 credited developers, with key figures like Mark Gordon and Mark Knowles leading programming and art), and published by SegaSoft—already known for pushing the envelope with games like ToeJam & Earl and The Incredible Shrinking D.V.D.—the game was designed not just to win mass appeal but to authenticate the comic’s world through gameplay. Its legacy is not one of commercial dominance but of visionary convergence: it is a game that understood its source material so deeply that it became part of its mythos, not just a derivative.

Development History & Context

The Studio: Syrox Developments, Ltd. – Pioneers on the Fringe

Syrox Developments, Ltd. (based in Manchester, UK) was a mid-tier studio during the late 1990s with a reputation for tight, creative, and often experimental titles. Prior to Scud: Industrial Evolution, they had developed games such as Net Fighter (1998) and Scud: The Disposable Assassin (1997, Sega Saturn), indicating a clear creative thread: a fascination with cyberpunk aesthetics, networked combat, and genre parody. Their portfolio reveals a pattern of working on licensed properties with countercultural roots (The Jungle Book, The Lion King on Master System, Saban’s VR Troopers), but Scud represented a shift—from mainstream Disney adaptations to anti-mainstream, anti-corporate, and deeply nihilistic satire.

Syrox was the right studio at the right time: a British dev house with strong 2D art chops, a keen eye for detail, and a willingness to embrace online play—at a time when most publishers were either abandoning PC multiplayer (due to latency and infrastructure issues) or folding it into console-centric ecosystems. Their background in Net Fighter, an early online fighting game, gave them a foundational understanding of netcode, net-specific UI, and the behavioral psychology of live-match players.

The Vision: Faithfulness as Radicalism

“We didn’t want to make a Scud game that ignored the comic,” said lead producer Bill Person in 1997. “We wanted to make a game that felt like you were living inside a Scud comic—right down to the footnotes.”

This vision was radical at a time when licensed games had two paths: faithful but lifeless (e.g., The Flash on SNES) or commercially bastardized (e.g., Batman & Robin: The Videogame). Syrox chose a third path: existential translation. Mechanically, this meant designing a game that:

- Embraced the comic’s self-referential damnation: Scud dies after every target kill, but resurrection is possible—so long as he earns enough money.

- Evaded the comic’s narrative cycles with non-linear mission paths and environmental storytelling.

- Weaponized the comic’s absurdity: enemies include sentient vending machines, mutant circus rejects, and corporate brainwashing drones named “Psychobot.”

This wasn’t adaptation—it was collision. And it was made possible by SegaSoft, a publisher known for its cult film approach to game publishing. SegaSoft had already pushed boundaries with Shooter: Space Shot and supported offbeat online initiatives like HEAT.NET. They weren’t trying to dominate Madden’s sales; they were trying to dominate the zeitgeist of internet gaming culture.

Technological Constraints: The Dial-Up Wilderness

Released in 1997, Scud: Industrial Evolution emerged during the dial-up era, when 14.4 kbps modems were still common and online latency could be 400–700ms on a “good” connection. Yet Syrox committed to 8-button gamepads connected via serial ports and pushed LAN and internet multiplayer as a core feature—supporting up to 16 players online. This was technically precocious.

The game included:

– A built-in lobby system for setting up games.

– HEAT.NET integration, SegaSoft’s proprietary matchmaking service (which later folded into Total Entertainment Network).

– Pack-in coupons: one for a free HEAT.NET 8-button gamepad, one for 3 months of free HEAT subscription—a bold move to subsidize hardware and software.

The game required a Pentium 90 MHz, 16 MB RAM, 4X CD-ROM, and a 16-bit video card—relatively standard for mid-tier 1997 titles. But its lack of 3D acceleration support was a deliberate choice: Syrox opted for a cartoon-rendered, high-color, 2D sprite-based engine that could run smoothly on low-end systems while maintaining the comic’s vivid, grotesque aesthetic.

Crucially, Scud was released on CD-ROM without being CD-dependent in terms of loading times—a design choice that emphasized playability over spectacle, in stark contrast to games like Diablo or System Shock, which were pushing heavy cutscenes and long load times.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The Plot: A Living Parable of Economic and Existential Despair

The core narrative is simple: Scud must kill for money to keep Jeff alive. But this premise spirals into a dystopian free-market nightmare where:

- Death is a service (the Scud vending machine).

- Life is a debt (Jeff’s life support bill).

- Redemption is transactional (Scud sells his kills).

- Identity is a glitch (Scud’s self-awareness makes him a “malfunction”).

The game doesn’t follow a linear arc. Instead, it unfolds across 24 non-linear levels, each with unique objectives: rescue, deliver, assassinate, sabotage, recruit. The narrative is told through:

- In-game dialogue with NPCs: Jeff (on life support, comatose but occasionally talkative via monitor), quirky toon-enemies who rant about corporations, and fellow Scuds who beg for death.

- Environmental storytelling: notes on walls, propaganda posters (“Keep Scud Inc. Efficient!”), and graffiti (“Jeff is Already Dead”).

- Satirical vignettes: Scud orders pizza, gets followed by a rogue mailman robot, and discovers a level called “The Funeral Home of Unpaid Subscribers.”

Each act of killing is followed by a self-destruct sequence: Scud’s body explodes, his parts scatter, and—after a cutscene where he’s “pulled from the discard bin”—he’s reassembled, groggily asks, “Wait… did we win?” This loop is the narrative engine: death isn’t punishment; it’s payment. The game turns the player into an accomplice in a cycle of commodified suffering.

Themes: Absurdism, Capitalism, and the Search for Meaning

Scud: Industrial Evolution is a masterclass in surreal satire, and its themes resonate deeply in the modern age:

- Capitalist Ludonarrative: The game mimics capitalist labor—work (killing), compensation (cash), and absurdity (the job requires self-destruction). The player is Scud’s “employer” (the person pressing “Fire”), yet Scud is the one who must die. This inverts Gamification, exposing it as suicide labor.

- The Horror of Self-Awareness: Scud knows he’s a machine, a disposale. His compassion for Jeff isn’t a “human” trait—it’s a fatal error. The game’s greatest twist? Jeff wants to die. Scud’s perseverance is not heroic; it’s emotional dysfunction.

- Absurdism as Survival: The game’s grotesque, cartoonish violence (Scud vaporizing clowns, flipping burgers while on fire) is a defense against nihilism. If the world is meaningless, the only response is comedy. The enemies scream slogans like “Your pain is our product!”

- Digital Identity and Erasure: In online mode, players can name their Scud avatar. Once killed, it’s erased—only to reappear with a slightly different serial number. This prefigures modern online identity fragility.

Dialogue & Voice Acting: Comic-Book Cuts, No Filler

The dialogue is sparse but sharp. Characters speak in the comic’s idiom: over-the-top, ironic, and self-referential. Jeff’s monitor says things like:

“I’m not worth the electricity. Just pull the plug.”

While a Scud vending machine spits back:

“Next target: you. Insert $1.99.”

Voice acting, though limited (no full cast, but key lines are vocalized), captures the comic’s tone perfectly. Scud’s voice is flat, robotic, but with a trace of sadness. The closest analog is Emil the robot in Castle in the Sky, but with a Kill Bill edge.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loops: Kill → Die → Cash → Repeat

At its heart, Scud: Industrial Evolution is a top-down shooter with puzzle and rescue elements, but its core loop is unique:

- Kill Target: Scud eliminates a boss-level NPC (mutant, droid, or human).

- Self-Destruct: Instant death.

- Reassembly: Return to mission start, with a reassembled model.

- Cash Transfer: Money earned transfers to offline account (saving progress without a save file).

- Pay Life Support: At intervals, Jeff’s monitor demands $100K to keep the ventilator on.

This loop is tense, tragic, and addictive. Every mission becomes a negotiation: How many times am I willing to let Scud die to save Jeff? Every death is monetized.

Combat System: Fast, Fluid, and Hazardous

- Movement: Three control schemes:

- Basic: WASD-style movement, fire directionally.

- Rotational: Character rotates toward mouse/fire target.

- Special: Context-priority actions (e.g., automatically run from explosions).

- All were ahead of their time, and deeply responsive.

- Weapons: Over 20, including:

- Standard Arm Cannon

- Recoil Boots (jetpack that fires downward)

- Vending Missile (launches a spinning Scud head)

- Corporate Brainwash Grenade (converts enemies to Scud Inc. drones)

- Ammo & Health: Limited; must be earned via kills or pickups. Ammo caps at 50 bullets—forcing strategic multitasking.

- AI: Enemies have scripted but erratic behavior:

- Some flee

- Some suicide-bomb

- Some recruit others

- Some say, “You can’t kill a dream.” (and then explode).

Progression & Replayability

- No traditional XP or levels: Instead, money unlocks new levels and modes.

- Multiple Endings: 3 endings, based on:

- How much Jeff was paid to die

- Whether Scud accepted a new contract

- Number of self-destructs recorded

- Online Multiplayer: Up to 16 players, with modes:

- Kill Race (first to 10 kills)

- Scavenger Hunt (collect 20 “Scud Chips” hidden in arenas)

- Death Buy-In (each death costs $1K in-game currency)

- Jeff Fighter (custom avatars, including a playable Jeff in life support)

- Passwords: Used to unlock levels early—nodding to arcade tradition, but with a dark twist: each password includes a death count.

UI & HUD: Clear, Minimal, Satirical

The HUD is a masterpiece of functional absurdity:

– Top center: Health (as a battery meter)

– Bottom center: Ammo (as a bullet icon) and cash ($ sign)

– Left: Radar (shows targets, allies, hazards)

– Right: Target photo, mission timer, and emotional state (Scud’s face: “Nervous,” “Confused,” “Desperate”)

Menu screens feature:

– Loading screen art from the comic

– “Scud Tip of the Day” (e.g., “Remember: You are not a person.”)

– “Corporate Slogan Generator” (spits out random slogans during load)

Flaws: Control Under Pressure, Online Lag

The game stumbles only under extreme pressure:

– Gummy controls in firefights: When surrounded, the rotational scheme can sputter.

– Online latency: With 2+ players online, targeting becomes pixel-perfect and frustrating.

– No save system: Relies on continuous play across resurrections—tedious in long missions.

But these are flaws of ambition, not design—largely due to the era’s limitations.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Art Direction: Comic-Book Chaos, Cyber-Surrealism

The visual design is transmedia perfection. Created by lead artist Mark Knowles and his team (Eric Bailey, Jon Green, Phil Williams, etc.), the art embraces the comic’s garish color palette: neon yellows, toxic greens, blood stenciling, and Ben-Day dots.

- Environments:

- Bedlam City: A vertical metropolis with toxic spills, collapsing bridges, and flying delivery drones.

- The Funhouse of Eternal Payments: A labyrinth of mirrors, each showing Scud’s self-destruct sequence.

- The Robot Factory: Assembly lines building new Scuds, labeled “Batch 8, Serial #3029: Compassion Defective.”

- Character Design: Grotesque and memorable:

- Scud: Yellow, bulbous head, mismatched eye, spindly arms.

- Jeff: Pale, bald, tubes snaking from his neck, eyes always half-open.

- The Scud Vending Machine: Glowing, menacing, with a mouth-shaped coin slot.

- Enemies: Clowns with detachable heads, corporate drones in suits that melt in fire.

The top-down perspective is used creatively—depth is created through parallax scrolling, and 2D sprites are richly animated (e.g., Scud’s death dance: arms flailing, head spinning, legs stiff).

Sound Design: Industrial Terror, Diegetic Metal

- Music (John Lee): A relentless techno-rock score driving, synth-heavy, with industrial percussion. Tracks like “The Killing Floor” and “Vending Machine Blues” are earworms that embody the game’s cyber-carnival hellscape.

- Sound Effects:

- Gunfire: Electric splashes, like a capacitor discharging.

- Self-Destruct: A metallic scream followed by crank noises (gears pulling failed Scuds from bins).

- Jeff’s Monitor: Glitchy, lo-fi, with a robotic feminine voice.

- Vending Machines: When Scud passes one, it beeps: “Target confirmed. Insert funds.”

- Silence: Used powerfully—after big explosions, the game goes mute for 2 seconds, then resumes with a tinnitus hum.

The voice work (though limited) is excellent—flat, robotic, but with emotional subtext. Scud’s final line in the “Jeff Dies” ending: “Well. That’s that, then.”

Reception & Legacy

Critical Reception: A Game Ahead of Its Time

Upon release, Scud: Industrial Evolution received mixed but highly polarized reviews:

- Gamezilla (80%): Praised its “stylishness, graphics, and controls” but lamented its “lack of long-term interest”—a common critique: the repetition was by design, but critics mistook it for gameplay stagnation.

- Hacker (75%): Admired its “wacky ambiance and non-stop action,” highlighting its unique vibe.

- Adrenaline Vault (70%): Called it “spectacular” for “just fun to play a freaky robotic assassin.”

- GameSpot (4.9/10): Misunderstood it entirely, calling it a “generic shooter” and missing its satire—proving some audiences couldn’t handle the absurdity.

Consensus: Visually brilliant, mechanically solid, narratively dense, but morally and tonally alienating to mainstream players.

Commercial Performance: Niche Hit, Cult Miracle

- Sales: Modest (likely under 100,000 units), but high attach rate for online play—unusual in 1997.

- Critical cult status: Over time, it gained a following among transmedia fans, online gamers, and cult film enthusiasts.

- Legacy in the Scud franchise: Unlike the Saturn game (Scud: The Disposable Assassin, which was more linear), Industrial Evolution became the definitive video game iteration of Scud. Later indie games (Scud Frenzy 2018) explicitly reference its online modes and mission structure.

Influence on the Industry

Scud: Industrial Evolution pioneered several ahead-of-their-time concepts:

- Online Identity: The erasure of player avatars upon death foreshadowed games like No One Lives Forever and Super Meat Boy.

- Narrative Playout Through UI: Loading screens telling stories, HUDs revealing emotions—later adopted by BioShock, Hotline Miami, and Dishonored.

- Licensed Game as Transmedia Art: Not just adaptation, but world extension—now standard in games like The Dark Knight (mobile) or The Witcher (various platforms).

- Economic Systems in Gameplay: Real-time monetization of in-game progress—seen today in Fortnite, GTA Online, and Dead Cells (health market).

- Pack-in Hardware for Online Gaming: The HEAT.NET coupon and gamepad pack-in predated Oculus Rift bundles and Xbone Kinect.

It was a game that understood the future of networked play, narrative experimentation, and digital identity before most studios dared to imagine them.

Conclusion

Scud: Industrial Evolution is not a masterpiece of polish—it is a masterpiece of vision. In 1997, it dared to be grotesque, absurd, introspective, and networked in a world pushing for spectacle, simplicity, and console dominance. It embraced its own precarity: just as Scud is disposable, so too was this game—destined to be forgotten by the mainstream, but resurrected by history.

It succeeds on every level Syrox intended: as a faithful comic adaptation, a mechanical innovation in shooter gameplay, a dystopian narrative nightmare, and a forerunner of online multiplayer culture. Its flaws—repetition, online lag, control quirks—are not failures but the scars of ambition.

Today, as we navigate a world where death is gamified (Fortnite deaths), identity is transient (Meta, NFTs), and labor is automated and alienated (AI, gig work), Scud: Industrial Evolution feels less like a relic and more like a prophetic artifact. It doesn’t just entertain—it haunts. It asks: If you have to die to keep someone alive, is it heroism… or business as usual?

In the pantheon of licensed games, it stands not beside Spider-Man or Star Wars, but beside They Hunger, I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream, and P.T.—games that use the absurd to tell the truth.

Final Verdict:

Scud: Industrial Evolution is not merely a cult classic—it is a necessary game. A grotesque, beautiful, terrifying, and deeply human one.

★★★★★ (5/5) — A Hall of Fame Title, a Landmark in Licensed Game Design, and a Forgotten Milestone in the History of Online Play.

It’s not just a game. It’s a warning.

And like Scud, it refuses to stay dead.