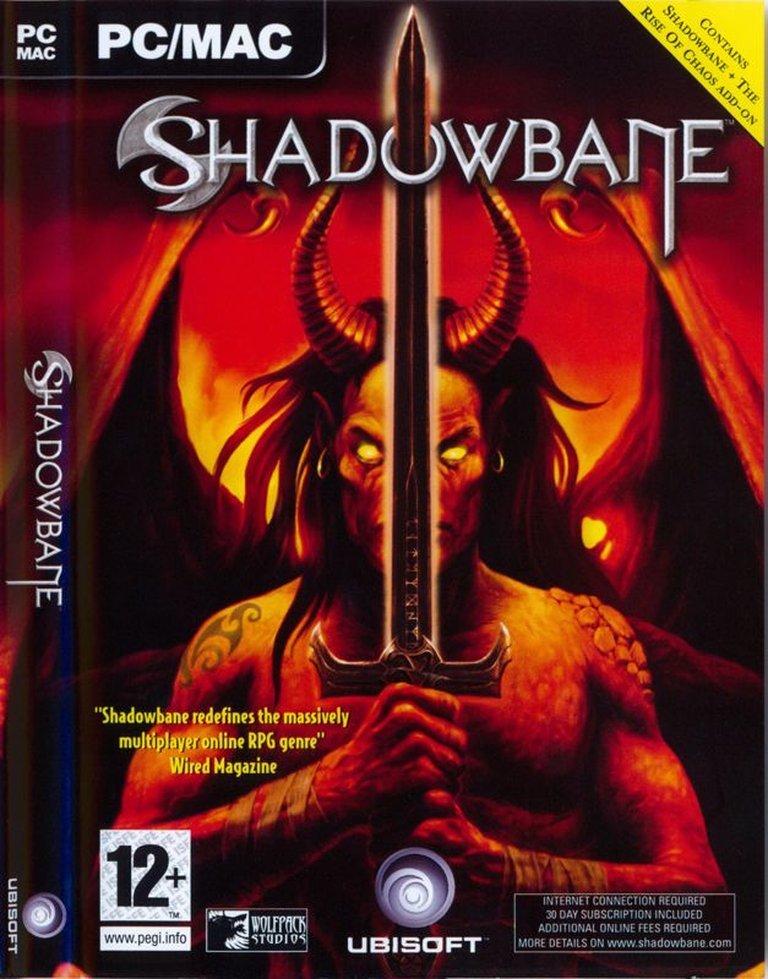

- Release Year: 2004

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: En-Tranz Entertainment, Ubi Soft Entertainment Software

- Genre: Compilation

- Game Mode: Online PVP

- Average Score: 48/100

Description

Shadowbane / Shadowbane: The Rise of Chaos is a compilation package containing the original 2003 game and its expansion, set in a medieval fantasy world where players engage in role-playing experiences with both first-person and third-person perspectives. Developed by Wolfpack Studios and published by En-Tranz Entertainment and Ubisoft, this online multiplayer title emphasizes persistent warfare, city-building, and large-scale guild conflicts in a dynamic persistent world.

Gameplay Videos

Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (48/100): Best team and solo PVP game ever made.

Shadowbane / Shadowbane: The Rise of Chaos: Review

In the pantheon of massively multiplayer online role-playing games, few titles are as simultaneously revered and reviled as Shadowbane. Released in 2003 and later bundled with its first expansion, The Rise of Chaos, into a single compilation in 2004, Shadowbane was not merely a game but a grand, ambitious experiment. It was a world designed from the ground up to be a crucible for political machination, territorial warfare, and raw, unfiltered player conflict. While its contemporaries like EverQuest and World of Warcraft were meticulously curated theme parks, Shadowbane was a savage, untamed wilderness, a digital sandbox for the ruthless. Its legacy is one of profound influence marred by technical and design flaws, leaving it as a cult classic—a testament to a vision of MMOs that was, and remains, aggressively player-driven. This review will delve into the intricate history, complex mechanics, and lasting impact of Shadowbane, a game that dared to ask its players not to simply save the world, but to conquer it.

Development History & Context

To understand Shadowbane, one must understand its creators. The game was developed by Wolfpack Studios Inc., a studio founded by a group of passionate developers, including Josef Hall, J. Todd Coleman, Patrick Blanton, and Robert Marsa. This team was steeped in the traditions of early text-based MUDs (Multi-User Dungeons) and graphical MUDs like Meridian 59, where player interaction, including player-versus-player (PvP) conflict, was the central pillar of the experience. Their vision was to create an MMORPG that moved beyond the repetitive monster-hunting and static questing that was becoming the genre’s norm, and instead build a persistent world driven by high-stakes player politics and territorial control.

This vision was born from a deep understanding of the nascent MMORPG market of the late 1990s and early 2000s. The genre was in its adolescence, dominated by the social and collaborative structures of games like Ultima Online and the more regimented, PvE-focused gameplay of EverQuest. Wolfpack Studios aimed to create a “dark fantasy” world, as described in the game’s official synopsis, where players would be the primary agents of change, not just spectators.

Technologically, Shadowbane was a product of its time. Released in March 2003 for Windows, with a Macintosh version following shortly after, the game was built on custom middleware, utilizing the Bink Video engine for its cutscenes. It ran on a subscription-based business model, requiring players to pay a monthly fee in addition to the initial purchase of the game software on CD-ROM. The technological constraints were significant; the game was known for its dated graphics and performance issues, especially during large-scale battles. Yet, its most ambitious feature was its server architecture. Unlike its competitors, which hosted players on numerous mirrored “shards” or servers, Shadowbane was designed to host all its players on a single, massive, interconnected world. This was a monumental technical undertaking for its era, aimed at fostering a truly global, player-centric community. The game was published by Ubi Soft Entertainment Software and En-Tranz Entertainment, which helped bring it to a wider audience.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The narrative of Shadowbane is less a traditional, developer-authored story and more a rich, foundational lore designed to serve as the primary fuel for player-driven conflict. The game is set in the world of Aerynth during the “Age of Strife,” a period of cataclysmic collapse following the destruction of the world’s god-like beings, the Helian. This apocalyptic backstory immediately establishes the game’s core theme: the fall of a previous order and the desperate struggle to build a new one from the ashes.

The world is not a blank slate; it is a fragmented continent, with ruined cities and scarred landscapes serving as monuments to a lost golden age. This setting provides a powerful justification for the game’s central gameplay loop: the founding of player-run nations. The lore, crafted extensively by writer Sam “Meridian” Johnson, was not delivered through quest text but was woven into the very fabric of the game’s factions. Players could choose from ten distinct races, including Humans, Elves, Dwarves, and more exotic choices like Minotaurs and Irekei (desert-dwelling elves), each with a unique history, culture, and inherent rivalries. These racial hatreds were not mere flavor text; they were designed to be permanent, in-game mechanics that would ignite wars and fuel alliances for years. For example, the deeply spiritual Elves would find themselves in opposition to the savage Minotaurs and the fanatical Irekei, providing a built-in narrative engine for endless conflict.

Beyond races, the world was populated by “Feature Characters” (FCs), important non-player characters portrayed by live actors hired by the developers. These FCs, such as the enigmatic Bane or the vengeful Kael, would stir up trouble, make grand declarations, and offer quests that would have real, lasting consequences on the world map. They were living plot devices, their actions designed to create power vacuums and opportunities for player cities to rise or fall.

The ultimate narrative goal for a player-run nation was not just to defeat monsters, but to achieve victory through the “Tree of Life” system. By controlling a city and its corresponding Tree of Life, a nation could exert dominance over vast territories of the world map. The ultimate expression of this narrative was the “World Tree,” a central objective for the most powerful alliances. Controlling the World Tree meant achieving a form of server-wide victory, a definitive end to the Age of Strife and the dawn of a new era, albeit one likely to be defined by the victor. This created a grand, overarching narrative arc that was entirely player-authored, making the story of any server a unique epic of betrayal, conquest, and glory.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, Shadowbane is a game about empire-building. The gameplay loop is a relentless cycle of character progression, territory acquisition, and large-scale warfare.

Character Progression: Players could choose from over 20 character classes, which were a radical departure from the rigid archetypes of other MMOs. The game utilized a “discipline” system that allowed for unprecedented customization. Players would choose a base class (a Fighter, a Mage, a Rogue, a Healer) and then “multi-class” by selecting secondary disciplines. This led to thousands of potential character builds, from a Warrior who also learned the ways of a Bard for crowd control, to a Mage who picked up rogue skills for stealth and lockpicking. This freedom allowed for incredible specialization but also led to a steep learning curve and, eventually, “flavor of the month” builds that were discovered to be overpowered by the player base.

PvP and City Building: The heart of the game was its PvP combat. Unlike systems with flagging mechanics or safe zones, Shadowbane was a world where conflict was the default state. Any player could be attacked by another, anywhere, except within the immediate vicinity of a city’s guards. This constant threat of violence was the key to the entire design.

The most innovative system was the city-building and nation-management gameplay. Players could band together to form “guilds,” which could then purchase a charter to found a city. This was not just a cosmetic feature; building a city was a major undertaking requiring immense resources. Players would construct walls, buildings, shops, and most importantly, a Tree of Life. The Tree of Life was the city’s anchor; as long as it stood, the city was safe. This single mechanic elevated Shadowbane from an RPG into a grand strategy game with RPG elements. Nations, alliances of multiple guilds, could claim entire regions of the world map, building keeps and outposts that would generate gold and resources for their members.

Combat and UI: The combat itself was action-oriented, utilizing a combination of hotbar abilities and positioning. It was lauded for its tactical depth in small-scale team fights but often criticized for being chaotic and difficult to control during massive, hundred-player-plus battles. The user interface (UI) was notoriously clunky, with a complex array of windows for managing a character’s stats, inventory, guild diplomacy, and city assets. This was a double-edged sword: it was overwhelming for new players but offered a staggering level of control for veteran leaders who needed to manage entire nations.

Flaws: The systems were brilliant in theory but plagued by execution. The “single shard” world suffered from severe performance lag during large sieges, turning epic battles into frustrating slideshows. The freedom of the class system led to balance issues, and the harsh, unforgiving nature of the world made it incredibly difficult for new players to get started, often leading to swift and humiliating deaths at the hands of veteran players. The monthly subscription fee combined with this harsh learning curve created a high barrier to entry, contributing to a relatively small but fiercely dedicated player base.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The world of Aerynth was a dark and oppressive fantasy landscape, a stark contrast to the more vibrant and polished worlds of its competitors. The art direction was functional but dated, even at the time of its release. Character models were blocky, animations were stiff, and the environments were often repetitive textures of rock and dirt. However, the art served its purpose: it created a believable, harsh frontier where survival was a constant struggle. The ruins of ancient civilizations dotted the landscape, serving as visual reminders of the world’s tragic history and providing locations for dungeons and resources.

The sound design was similarly functional. The musical score was suitably epic and moody, helping to establish the grim tone of the Age of Strife. Sound effects were standard for the genre—the clank of swords, the roar of a spell, the grunt of a monster. Voice acting was limited primarily to the pre-rendered cutscenes and the occasional Feature Character, but it was effective in lending a sense of weight and importance to the world’s lore.

Ultimately, the art and sound were not there to be admired on their own merits but to serve the gameplay. They created the atmospheric backdrop for the player-driven drama, a world that felt lived-in and dangerous, where the focus was always on the other players populating it, rather than on the beauty of the environment itself.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its initial release in 2003, Shadowbane received a mixed-to-positive reception from critics, with an average score of 67% on MobyGames, based on 16 reviews. Many praised its ambitious vision, deep political systems, and the sheer thrill of its large-scale player battles. It was rightly recognized as a unique and innovative title in the crowded MMO space. However, this praise was consistently tempered by heavy criticism for its poor graphics, numerous bugs, and steep learning curve. Players, on average, rated it a 2.4 out of 5, indicating a significant disconnect between the game’s ambitious design and its flawed execution.

Commercially, Shadowbane was not a blockbuster. It struggled to maintain a large subscriber base against the rising tide of more accessible and polished games like World of Warcraft, which launched later in 2004. The game’s initial population was strong, but its harsh nature and technical issues led to high attrition rates.

Yet, Shadowbane‘s legacy has grown in the years since its shutdown in 2006. It is now remembered as a cult classic and a profoundly influential title. Its core concepts—player-driven politics, territorial control, and the integration of strategic empire-building into an RPG—have echoes in numerous modern games. Titles like EVE Online with its complex player-run corporations and political landscape, and various “RvR” (Realm vs. Realm) systems in games like Dark Age of Camelot, owe a significant debt to Shadowbane‘s template. The idea that a game’s most compelling content would be created by its own players, rather than scripted by developers, was a revolutionary concept that Shadowbane fully embraced.

Even today, in the era of “sandbox” MMOs and survival games, the spirit of Shadowbane lives on. As one player’s review on MobyGames poignantly states, “I miss this game still today… The best team and solo PVP game ever made… Someone needs to be willing to waste millions to make a new version of this game because PVP today is just MOBA crap.” This sentiment captures the enduring power of Shadowbane‘s vision: a world where players are the heroes, villains, kings, and conquerors, where the greatest story is the one you write yourself.

Conclusion

Shadowbane / Shadowbane: The Rise of Chaos is a paradox. It is a game that is, by virtually every conventional metric, a failure. Its graphics were dated, its launch was buggy, its player base was small, and it was ultimately shut down by its publisher. Yet, it is also one of the most important and influential MMORPGs ever made. It represents a bold, almost foolhardy, attempt to create a true virtual world, a digital nation-state simulator where the primary antagonist was not a dragon, but the player in the next guild over.

Its genius lies not in its polish or perfection, but in its unrelenting focus on player agency. Shadowbane stripped away the safety rails and gave its players the tools to build, destroy, and dominate. It was a game that rewarded ruthlessness, celebrated political maneuvering, and turned entire servers into grand, living epics of conflict. While most MMOs of its era were becoming increasingly themepark-like, Shadowbane defiantly remained a savage wilderness. For its dedicated fans, it remains the gold standard for PvP and political simulation, a flawed masterpiece whose ambitious vision has yet to be fully realized. It stands as a towering monument to the potential of player-driven worlds and a cautionary tale about the perils of launching an idea before its time. In the annals of video game history, Shadowbane is not just a game; it is a legend.