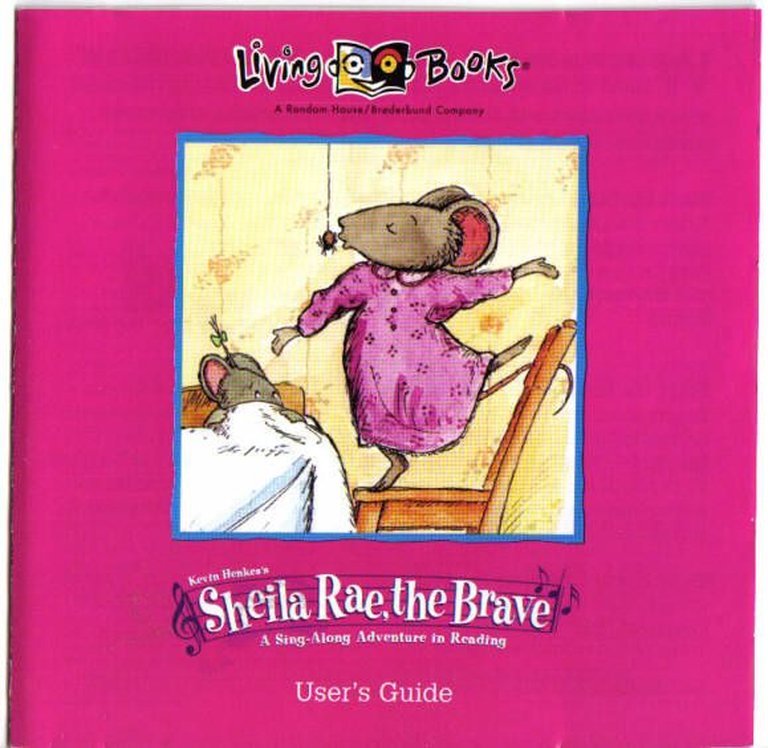

- Release Year: 1996

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows 16-bit, Windows

- Publisher: Brøderbund Software, Inc., Jordan Freeman Group, LLC, Wanderful Inc.

- Developer: Living Books

- Genre: Adventure, Educational, Reading, writing

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Hidden surprises, Interactive storybook, Sing Along section, Treasure Hunt game

- Setting: Town

- Average Score: 88/100

Description

Sheila Rae, the Brave is an interactive educational adventure game based on the beloved children’s book by Kevin Henkes, released in 1996 as part of the Living Books series. The game follows Sheila Rae, a courageous little mouse, as she explores her town, interacts with family and friends, and ultimately learns an important lesson about true bravery after becoming lost. Designed for young readers on Windows and Macintosh platforms, the title features animated storytelling, clickable hidden surprises, a Treasure Hunt minigame, and a Sing-Along section with original character songs, promoting literacy and engagement through playful interactivity. Developed by Living Books and published by Brøderbund, the game is praised for its strong narrative, relatable themes, and appealing presentation tailored to early learners.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Sheila Rae, the Brave

PC

Sheila Rae, the Brave Free Download

Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (81/100): Shelia Rae, the Brave is an interactive storybook based on the book by Kevin Henkes.

myabandonware.com (95.8/100): Played this game as a little girl back in the 90’s and 00’s! Seeing the pictures and the story brings me so much nostalgia!

imdb.com : Sheila Rae brags about how brave she is including kissing a spider, watching a lightning storm and attacking the monster in the closet.

Sheila Rae, the Brave: Review

Introduction: A Mouse-Sized Monument to Interactive Storytelling

“I am fearless, I am brave, nothing can make me afraid.”

These lyrics, singing out of a small rodent protagonist’s heart in Sheila Rae, the Brave, are more than just a catchy tune. They are the manifesto of an entire genre, and indeed, a foundational moment in the history of interactive educational storytelling. Released in 1996 by Living Books, a division of Brøderbund Software, Inc., Sheila Rae, the Brave was the eleventh entry in the celebrated Living Books series, a landmark in the paradigm shift toward digitalization of children’s literature. More than a mere digitization of Kevin Henkes’ beloved 1987 picture book, the game was an ambitious experiment: How could the tactile intimacy of a child reading a storybook be transformed into an engaging, immersive, interactive experience without losing its soul?

The game, beneath its deceptively simple exterior — a 2D animated mouse navigating her suburban world — encapsulates the core thesis of this review: Sheila Rae, the Brave was not just a successful adaptation of a picture book, but a visionary achievement in interactive storytelling for early childhood, whose influence resonates in modern edutainment, literacy software, and the very philosophy of play-based learning. Its enduring legacy is proven by its continued availability through digital platforms like Zoom Platform, its non-DRM preservation, and the nostalgic acclaim from generations who encountered it on their family Windows 3.x or 95 machines. This review will explore this achievement in depth, dissecting its development context, narrative innovations, gameplay mechanics, artistic expression, reception, and lasting impact on interactive media. I argue that Sheila Rae, the Brave deserves recognition as a seminal artifact in the evolution of children’s software — not merely as a nostalgic relic, but as a technologically determined, pedagogically intelligent, and artistically enduring benchmark in the history of gaming.

Development History & Context: The Mohawk Generation

The mid-1990s was a pivotal era for personal computing and software development. The Windows 3.x and Windows 95 platforms were the dominant environments, marked by increased graphical capabilities, CD-ROM storage (1X, 150 KB/s), and, crucially, greater affordability of multimedia PCs in homes and schools. This period saw a surge in research into children’s digital learning, with companies recognizing the potential for interactive CD-ROMs to deliver educational content in a way that was engaging, repeatable, and scalable.

Brøderbund Software, a household name since the early days of Apple II (with Choplifter, Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?), had long been a pioneer in edutainment. Their establishment of Living Books in the early 1990s was a direct response to this emerging market, aiming to digitize classic children’s picture books using the full suite of multimedia capabilities. Their primary innovation was the Mohawk Engine — a custom-built interactive book framework designed specifically for Living Books titles. The significance of this engine cannot be overstated. Unlike earlier attempts at “digital books” (text-based adventures or static hypertext), Mohawk allowed for frame-by-frame animation, synchronized voice narration, interactive objects, background music, and sound effects, and looped animations — all with robust mouse-driven interactivity. It was, for its time, a highly sophisticated content delivery system for non-linear storytelling.

The development of Sheila Rae, the Brave was led by a large, interdisciplinary team of 89 credited professionals across multiple studios:

* Living Books (California): Core development, project direction (Bridget Erdmann, Pat Farrell, Markus Schlichting, Tami Tsark), sound design (Pat Farrell, Elizabeth Stuart), Living Books animators (Christine Schnarr, Spartaco Margioni, etc.).

* Michael Sporn Animation, Inc. (New York): Primary animation studio responsible for the visual style and fluidity of the characters and environments (Michael Sporn, Jason McDonald, John Leard, Adrian Urquidez).

This bicoastal collaboration was essential. Sporn’s studio brought the hand-drawn, expressive, and slightly exaggerated aesthetic that defined the look of the entire Living Books series — a style that directly translated Henkes’ original line drawings into digital life, preserving the whimsical charm and emotional clarity of the source material. Meanwhile, Living Books’ engineers and designers focused on interactivity, game logic, and the Mohawk Engine infrastructure. The technological constraints were significant:

* Limited RAM (4MB minimum, requiring careful memory management).

* CD-ROM reliance (data streaming for animation and audio loops).

* CPU (Intel i386 minimum) far below modern standards.

* Graphical resolution tied to the era (SVGA, 640×480 typical).

The “map game” (the hidden object/clickable treasure hunt) was acknowledged as “taking a lot of space up,” leading to exclusions of demo content for other titles — a testament to the data management challenges of building such richly interactive CD-ROMs. The engine required precise hot-spot tagging, animation triggers, conditional logic (e.g., only playing the spider-kissing animation if the spider is clicked before the lightning), and synchronized audio playback — all while maintaining frame-rate stability.

The release context in 1996 is crucial. The Living Books series had already achieved notable success with titles like Dr. Seuss’s ABC (1995) and Harry and the Haunted House (1994). There was both momentum and expectation. The educational software market saw competitors like Super Solvers (Midnight Rescue!, 1989, rereleased in 1995) and Humongous Entertainment’s first entries (though Humongous itself, mentioned in Retrolorian, is an error — they weren’t established until 1993). However, Living Books carved a unique niche: not complex puzzles, but emergent exploration and emotional resonance via interactivity. Sheila Rae built directly on the “read along” formula established by its predecessor, adding crucial new layers: the Treasure Hunt map, the Sing Along section, and the extensive demo suite. It was positioned not just as a book, but as an experience bundle, leveraging the CD-ROM’s capacity for multiple modes of engagement.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Crucible of Bravery

At its core, Sheila Rae, the Brave adapts Kevin Henkes’ 1987 picture book, staying remarkably faithful to its plot, character, and primary themes while expanding the world through interactivity. The narrative structure is book-like, presented in chapters or “pages” via animated scenes and narrated text:

1. Chapters 1-5 (“She Does Daredevil Stunts”, “She Kisses the Spider”): Sheila Rae, a small, energetic field mouse, lives in a charming suburban town. The narrator introduces her as exceptionally brave, listing her acts of daring: kissing a spider, watching a lightning storm, attacking the monster in the closet, performing dangerous bike stunts, tying up a school bully with her jump rope, ignoring bullies, and remaining calm during a thunderstorm. The tone is confident, even boastful.

2. Chapter 6 (“I Am Brave”): Sheila Rae sings her signature song, “I am fearless, I am brave, nothing can make me afraid,” with Anna Deering and Laura Deering providing her singing voice. This is the emotional peak, a declaration of uber-confidence.

3. Chapter 7 (“Getting Lost”): While walking home, Sheila Rae takes a shortcut through the forest to beat her neighbor Louise (a large, non-threatening cat). There, the true test of bravery begins. Decreasing sound effects (crickets, leaf rustling), diminishing light, brush strokes suggesting approaching predators, and Sheila Rae’s own growing expression of fear signal the narrative shift.

4. Chapter 8 (“The True Meaning of Bravery”): Lost and scared, Sheila Rae calls for help. Her mother Mamie Rheingold (voice actress) arrives. Sheila Rae admits she was “a little scared,” and her mother becomes the true source of bravery, guiding her home. The story concludes with a powerful message: Brave people aren’t defined by looking fear in the eye, but by having someone there to guide them when they do get scared. The final text reads: “Sometimes, the bravest thing you can do is to admit that you are afraid.”

Character Analysis:

* Sheila Rae: Far from a one-dimensional “brave” character, she embodies “cognitive dissonance” — her external bravado vs. her internal vulnerability. Her acts of “bravery” are often humorous (kissing a tiny spider, braving classroom noises) and performative (tying up the bully). Her true bravery lies in her eventual self-awareness when lost. The game fines her voice (Mamie Rheingold: slightly high-pitched, energetic, deliberate) to emphasize her smallness. The interactive layer shows her small joys (swinging, gasping at a plane), making her relatable.

* Mother (Mamie Rheingold): Represents quiet, understated courage and unconditional love. She doesn’t perform stunts; she listens and acts. Her voice is calm, deep, and steady, grounding Sheila when she panics. She embodies “safe harbor”.

* Louise (Anna & Laura Deering): The large neighbor cat, mentioned as teasing Sheila’s small size. She is a foil, creating social pressure to prove bravery. Her presence is the conflict inciting the forest shortcut.

* Narrator (Gina Leishman): Provides the omniscient, warm, and slightly humorous tone of the original book. She guides, observes, and frames the action. Her narration is the primary read-along text.

Thematic Exploration in Depth:

The game re-defines bravery through its structure and interactivity, going far beyond the simple “don’t be afraid” trope crucial for children:

- The Illusion of Perpetual Fearlessness (False Bravery): Sheila’s initial acts are willed, performative bravado, driven by social proving (Louise) and ego (“nothing can make me afraid”). The interactive animations highlight the mundane or absurd (kissing a tiny spider, jumping on a cat) — suggesting the artifice of this performance. Her own song becomes comically overblown.

- Fear as a Natural, Normal Emotion (True Vulnerability): When lost, the game uses sensory deprivation (fading sounds, darkness) and visual cues (Sheila’s small frame in large spaces, small eyes wide) to force the player to feel her fear. Unlike her controlled acts, this is reactive, helpless, and involuntary. The player witnesses the collapse of her bravado.

- The Power of Support Systems (The Bravest Act): The mother’s arrival isn’t a rescue; it’s an invitation to be human. Sheila’s verbal admission of fear is framed as strength, not weakness. This is the crucial thematic pivot. The mother doesn’t dismiss the fear; she acknowledges it (“Yes, it’s okay to be scared”) and then acts. Her bravery is practical, loving, and proactive.

- Bravery as Process, Not Achievement: Sheila learns via the experience. Later interactions (clicks in the final scenes) might show her swinging confidently — the confidence grounded in security, not denial. Her bravado transformed into resilience.

Dialogue & Language Development:

* Narrated Text: English text is large, clear, and synced phonetically with the narrator’s voice (Gina Leishman). This multi-sensory reinforcement is key for literacy — it teaches letter-sound correlation, word segmentation, and sentence structure. The language is simple, descriptive, and uses basic sentence types (declarative, imperative).

* Character Dialogue (Limited): Mostly non-dialogue vocalizations (giggles, gasps, screams) and the Sing Along song. The song is unexpectedly crucial: “I am fearless, I am brave” is a repetitive, rhyming lyric focusing on key adjectives. It is highly catchy (as user Emily L S notes, even remembered decades later), aiding memory and vocabulary. The lyrics contrast with the ending, creating cognitive dissonance “aha!” moment.

* Spanish Language Option: Available in some versions (as per IMDb), offering early bilingual labeling of objects/menu items, another tool for language exposure.

The narrative does not shy from fear; it centers it as a starting point for growth. The message — “it’s brave to admit you need help” — remains profoundly relevant and compassionate.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Architecture of Playful Discovery

The gameplay is not a traditional “game” with levels, challenges, or puzzles, but a non-linear interactive environment. The core loop is exploration-driven discovery:

1. The Narrative Cycle (Main Loop):

* Trigger: Player clicks the “Play” button or selects a scene.

* Narrative Sequence: The Mohawk Engine plays a linear, animated story sequence (approx. 30-60 seconds) with synchronized narrator voice (Gina Leishman) and on-screen text display. Music and sound effects (SFX) play (e.g., bike noise, spider rustle, thunder rumble).

* Interactive Exploration Phase: After the sequence ends, the screen becomes static, like a paused movie. The player gains primary agency: the mouse cursor transforms into a standard pointer (not a tool).

* Hidden Interaction Search: The player clicks anywhere on the screen to discover “hot spots” — areas that trigger short, non-essential animated vignettes. Examples: Clicking the spider makes it briefly hide under a leaf; clicking the thundercloud makes raindrops fall and Sheila’s hair droop; clicking the bully makes him blink; clicking Sheila’s fingers while counting numbers makes her digits wiggle; clicking the house window at night makes lights flicker; clicking the map of the forest reveals hidden animals. These are strictly additive, interruptible, and loop after completion.

* Objective (Implicit): To discover every possible hidden animation, maximizing engagement.

2. The Treasure Hunt (Map Game – Optional, Replayability Loop):

* Trigger: Accessible via a main menu “Treasure Hunt” option after the first narrative cycle.

* Format: A top-down map of Sheila Rae’s town (including the forest). Nodes (iconic locations: house, tree, park, school, forest edge, forest path, forest clearings, creek).

* Gameplay: Player clicks on nodes to “explore” them. Each node has 1-3 hidden objects (e.g., “glowing firefly,” “dancing mushroom,” “hummingbird,” “sparkly rock,” “floating soap bubble”) that need to be discovered over multiple visits. If not found, it’s a “miss.”

* Progression: Serverall visits required to 100% clear the map. Rewards: Achievement of completion, discoverable “easter egg” animations within the main scenes (e.g., hearing the mother’s whistle in the house), or unlocking demo content. Creates fuzzy completionism and encourages re-reading the main story to map up new nodes or use knowledge to find hidden items.

3. The Sing Along (Audio Playground – Engagement Loop):

* Trigger: Main menu “Sing Along” option.

* Format: A static scene (various settings: park, town, etc.) with Sheila Rae visible.

* Gameplay: The signature song “I am fearless, I am brave” plays. Lyrics displayed on-screen in the same way as narrated text. Player can click other characters (when present) or animals in the scene during the song to re-trigger short animations (e.g., clicking Louise makes her blink or meow). No new lyrics/objective; it’s a freeplay mode reinforcing the song and its associated animations.

* Function: Memory, vocabulary, fun. The catchy tune ensures recall (user Emily L S). The clickability maintains engagement.

4. The Demo Suite (Product Awareness – Embedded Loop):

* Trigger: Main menu “Demos” option.

* Format: A multiplescreen menu showcasing 7 other Living Books titles (Just Grandma and Me, The Tortoise and the Hare, Little Monster at School, Arthur’s Birthday, Harry and the Haunted House, The Berenstain Bears Get in a Fight, Dr. Seuss’s ABC). Selection launches a short (30-second) standalone interactive scene from the chosen game.

* Function: Product sampling and propaganda for the Living Books ecosystem. Demonstrates the Mohawk Engine’s versatility. A sales tool embedded in the experience (MobyGames, Angry Grandpa’s Wiki).

Systems Analysis:

| System | Function | Innovation/Flaw |

|---|---|---|

| Mohawk Engine (Core) | Animation, Scripting, Synchronization, UI, Save/Load (for Treasure Hunt) | Innovation: First robust engine for non-linear, high-FPS interactive books with hierarchical animation states, robust audio streaming, and save persistence. Flaw: Required significant development investment. |

| Hot-Spot Interaction (Primary Mechanic) | Enabling “goofy,” non-narrative animations | Innovation: Created emergent, playful engagement. The “aha!” moment of discovery. Flaw: Sometimes arbitrary or obscure; required trial and error. The lack of verbal cues (e.g., “try clicking the tree”) could be frustrating for very young, struggling readers. Children might accidentally click essential areas. |

| Treasure Hunt (Map Game) | Replayability, Completionist Target | Innovation: Gave purpose to repeated exploration outside the narrative. The fuzzy, probabilistic object appearance mimicked actual search. Flaw: No inherent educational purpose outside discovery; could feel like busywork. Save requirements (persistence between sessions) crucial for its function. |

| Sing Along | Memory, Vocabulary, Emotional Engagement | Innovation: Brilliantly used music and rhythm for learning. Passive participation encouraged. Flaw: Purely acoustic/visual, risked becoming background noise. |

| Demo Suite | Product Sampling | Innovation: Smart self-marketing. Flaw: Purely commercial, pulled players away from the main game flow. |

| UI/UX (Point-and-Click) | Intuitive for Startling Readers | Innovation: Leveraged iconic Windows interaction. No reading required for navigation (icons for Main Story, Map, Sing, Demos). Text was optional for interaction (could click icons). Flaw: Icons potentially unclear for some (e.g., map for Treasure Hunt). No controller support, only mouse. |

Character Progression: Zero. This is not an RPG. Sheila Rae’s “progression” is purely narrative and internal — shown in her facial expressions and the mother’s arrival. The only “progress” is found in the player’s discovery count (hot-spots, map items).

Load Times: CD-ROM dependent (1X speed). Narrative loading was fast. General interaction was near-instantaneous — a testament to Mohawk’s efficient loading of frame buffers and sound clips. However, the initial boot from the CD could be slow (up to 30-60 seconds on a slow drive).

The system is brilliantly designed for its audience: it minimizes frustration (no fail states, no complex paths, no complex UI controls), maximizes discovery (high density of mappable objects), goes beyond rote listening (active engagement), and frames learning within safe, joyful exploration — targeting ages 3-8 with effortless scalability in difficulty via increased observation time.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Animated Suburbia

Visual Direction & Art:

* Aesthetic: Hand-drawn, soft-cartoon. Visuals directly translate Kevin Henkes’ original line drawings into digital animation. Character designs are slightly exaggerated (Sheila Rae: big eyes, expressive mouth; Louise: large, purring cat; Mother: calm, sturdy). Environments are painterly: Green, sunlit lawns; cobblestone paths; tree-lined streets; a slightly whimsical, slightly rural American suburbia.

* Color Palette: Warm, primary, and inviting — greens, browns, yellows, blues. Contrast is high for visibility. Interiors are brightly lit; the dark forest is deep blues and grays.

* Animation (Michael Sporn, Living Books Animators): 2D frame-by-frame, surprisingly fluid for a CD-ROM (30 FPS). Sheila Rae’s movements are small, fast, giggling (anticipating the “sparkle” animation). Mother’s are calm, large, deliberate. Louise is slow, rolling purrs. Environmental animations (dancing grass, raindrops, spinning leaves, flickering house lights) were achieved with looped, short sequences — a technical marvel for the era.

* Art for Literacy: Text boxes are large, black-on-white or cream, using trusted font families (sans-serif). Text is always on-screen during narration. No “hide text” option, embedding reading literally into the gameplay.

Set Design & Atmosphere:

* Sheila’s House: Cute, cottage-like, with warm interior lighting, toys on the floor, bikes in the yard.

* Her School: Bright classroom with large windows, posters, playful hallway.

* The Town: A living diorama. Trees have secret hot-spots (birds, squirrels, flowers). Houses have windows to watch the goings-on (flashing lights, open curtains). The map in Treasure Hunt is a physical diagram on a piece of paper.

* The Forest: A deliberate contrast. Visuals become limited, darker, and more abstract. Bullet points of trees; small clearings; suggestions of paths. Sounds are ecological but tense.

* The Atmosphere: The game captures the specific feeling of a child’s suburban world — safety in the house/town, vulnerability in nature, pride in personal spaces (bike, treehouse). The “bravery” of the town is the exuberance of a bee on a flower, not a superhero. The forest is the unknown “other”.

Sound Design (Pat Farrell, Elizabeth Stuart):

* Music: Upbeat, playful, and whimsical. Uses light orchestral instruments (flute, strings, light brass). Theme music is fast tempon during the “daredevil” sequences, slower, hesitating during Sheila’s lost phase, and warm, resolving during the mother’s arrival. The Sing Along song is driven by a synth pop arrangement — contemporary for 1996, instantly memorable, and specifically designed for children’s voices (not trained singers).

* Sound Effects (SFX): Highly effective.

* Positive SFX (contrast town safety): Spinning bike wheels (rhythmic, metallic); giggles (high-pitched, child-like); giggles; doorbells (cheerful chime); the “pling” of the counter.

* Negative/Problematic SFX (forest tension): Crickets chirping (unbearable, repetitive); leaf rustling (subtle horror); raindrops (muffled, dropping); distant howls (ambiguous, scary); heavy boot steps (during the stormroom scene).

* Interactive SFX: Every hot-spot has its own unique “reward” sound — the spider rustle, the bully’s gurgle, the light flicker’s buzz — giving auditory confirmation of discovery.

* Narrator & Voice Acting (Gina Leishman, Mamie Rheingold, Anna/Laura Deering): The core sound layer. Gina Leishman’s narration is warm, slightly gentle, and never patronizing. Mamie Rheingold’s voice is the emotional anchor secret warmth and stability. Anna and Laura Deering (Louise) provide contrastingly purring, slightly mischievous sounds. The singing voice is upbeat and empowering, perfectly capturing Sheila’s bravado.

* Silence: The final scenes use measured silence (after the mother’s arrival) to build intimacy. The lack of background music during the cliffhanger (before mother arrives) increases tension.

Contribution to Experience: The art and sound work in harmony. The warm, bright visuals of the town and cheerful music create an atmosphere where Sheila’s early “bravery” is supported — it feels possible and safe. The dark, abstract visuals and tense, minimal sound (crickets, rustling) of the forest create a genuine sense of isolation and fear — making the mother’s arrival a deluge of love and safety. The high-density interactive sound effects and parcel animations reward exploration with auditory and visual feedback, encouraging the click-anywhere mechanic and dissipating the tedium of repetition. For the truly young player, the visual and auditory impression of the world — more than the text and narrative — is often the primary learning mechanism.

Reception & Legacy: The Harvest of Whimsy

Critical Reception at Launch (1996-1998):

* Overall Score: 81% average (MobyGames, based on 3 ratings — All Game Guide 90%, Feibel.de 83%, Macworld 70% — a strong score for a niche title).

* Praise:

* All Game Guide (90%): Called it “excellent” and emphasized the included booklet of suggestions (“other books with similar themes and activities that complement and supplement parts of the program”) — highlighting its extended educational value.

* Feibel.de (83%): Praised the “spannend gemachte Geschichten für die Kleinsten” (“excitingly made stories for the little ones”) and noted the enduring appeal of well-told children’s stories. Critiqued the sound quality (“Wann wird es mal einen besseren Sound geben?” – “When will the sound get better?”) — a clear reference to SFX and music resolution, a limitation of the era.

* CNET (Unscored, Verdict “Buy It”): Highlighted the Caldecott Honor-winner source, “humor, drama,” and “great (and definitely not prissy) role models for young girls” — making a crucial point about Sheila’s strength without “prissiness”.

* Macworld (70%): Called it an “engaging entry” and praised the addition of songs and games to the Living Books formula, seen as an improvement over earlier, more passive titles.

* Narrative: Critics immediately recognized the effective adaptation of Henkes’ message. The interactive layer was praised for deepening engagement without gimmickry.

* Limitations: The sound quality critique (Feibel.de) and Macworld’s lukewarm “70%” (compared to the others’ high scores) reflected mainstream critics’ comfort with or focus on broader technical standards, not the genre’s specific needs. The limited interactivity (only mouse) was not a major point.

Commercial Reception:

* Modest Success: No available sales figures. However, the large team (89), CD-ROM production, and continued presence in the Living Books series positioning (as “era-defining”) suggests favorable sales, particularly in North America and Germany (localized titles). Its inclusion in boxed compilations (“Harry und das Geisterhaus / Sheila Rae, die Mutige / Nur Oma und ich”, 2001) points to clear brand value.

* Distribution: Reached homes via brick-and-mortar software stores, school software catalogs, and direct mail. The CD format was now standard.

Legacy & Influence:

* Direct Influence on Living Books / Edutainment:

* Proved the formula’s longevity: Sheila Rae demonstrated that the “read along + hidden animations” template had critical and commercial juice. It directly informed successors like Stellaluna (1996) and Harry and the Magical Book (using a similar map game).

* Elevated the series: It expanded the original “read along” concept with active games (Treasure Hunt) and expanded media (Song), making it a more viable “interactive experience” that could compete with simple games.

* Mohawk Engine Legacy: The engine’s infrastructure remained viable until Living Books was retconned in the late 1990s to early 2000s, with assets eventually used for Wanderful Interactive Storybooks (now LuvBug Digital).

* Influence on Later Children’s Software & Design:

* The high-density per-page interactive objects principle was adopted by later edutainment titles (e.g., Curious George: Hide and Seek, various Reader Rabbit games on DVD-ROM).

* The multi-sensory approach (narrator + text + sound + animation + interactive SFX) became the blueprint for tablet-based children’s apps (though modern uses touch gestures, the concept is identical).

* The narrative of “learning through failure” (bravery as admitting fear) was seen in multiple children’s games and TV shows for years.

* The “demo suite” model (embedded product sampling within the game) was used in company-branded compilations.

* The use of music for vocabulary (catchy repeats) was adopted in multiple language learning apps.

* Cultural Impact & Preservation:

* Nostalgia: As user Emily L S (MyAbandonware) notes, the game “brings me so much nostalgia” and she remembers the lyrics 30+ years later — proof of its memorable design. The “Sing Along” tune remains a cultural artifact.

* Preservation: Available non-DRM via Zoom Platform, playable on DOSBox and ScummVM (which supports Mohawk). It is not abandonware but a bought digital relic. Listed on ClassicReload, LaunchBox, MyAbandonware, and Internet Archive, ensuring archival presence.

* Deconstruction Media: Referenced in YouTube commentaries, TikToks about ’90s computer games, and “The Living Books Game Book” (hypothetical deeper dives).

* Title Homages: The use of “Brave” in later titles (Brave Fencer Musashi, Disney•Pixar Brave) might draw a conceptual link to the theme of internal courage, though accidental.

Bye the late 1990s (Angry Grandpa’s Wiki): It was “discontinued in 1998” as physical CD-ROM production shifted, but its digital rebirth ensures its survival. It stands as a cornerstone of “golden age” Windows 3.x/95 edutainment — a time when games were designed to teach, not just entertain.

Conclusion: A Tapestry of Courage and Code

Sheila Rae, the Brave is not merely a text-adapted game; it is a masterclass in translational multimedia pedagogy. Its brilliance lies in its deliberate technological deterministic design (within the CD-ROM limits), its pedagogical intelligence (multi-sensory literacy, narrative emotional engineering), its gorgeous collaborative artistry (Henkes + Sporn + Farrell + Stuart + Erdmann), and its seamless integration of educational mechanics with joyful, unbounded discovery (hot-spots, map game, sing along).

The game’s legacy is multifaceted:

1. A Technical Milestone: It proved the Mohawk Engine’s power to deliver rich, interactive, non-linear books. It showed CD-ROM’s potential for recasting print media.

2. A Narrative Innovation: It re-interpreted a picture book not as a digitization, but as a new medium for exploring a theme — bravery — with interactive depth the book format couldn’t achieve (e.g., the sensory deprivation of the forest).

3. A Pedagogical Benchmark: Its read-along + narrator + text + interactive discovery + supporting curriculum (booklet) model is the template for countless children’s apps today.

4. A Cultural Artifact: Its catchy song, iconic character (Sheila Rae), and ubiquitous availability have embedded it in Gen Z and early Millennial nostalgia for the “computer game” as a positive, unpressured exploration space.

It avoided the pitfalls of many edutainment titles (resistant work, forced puzzles, patronizing tone). It was not a “game” to be “won”; it was an interactive story to be deeply experienced — with children drawn in by the promise of “find this hidden thing right now” rather than “do this work.”

For the historian of video games — especially for the history of interactive media for young audiences — Sheila Rae, the Brave stands as an essential artefact. It is not the most complex game, nor the most technically ambitious, but it is a flawless integration of narrative, teaching, technology, and joy. In the record of digital storytelling, its place is secure, brilliant, and brave.

Final Verdict: Sheila Rae, the Brave is a foundational masterpiece of interactive children’s software. It deserves its legendary status within edutainment history, not as a quaint relic, but as a visionary, emotionally intelligent, and technically rewarding experience that remains remarkably accessible, engaging, and pedagogically vital over a quarter of a century after its release. It is, quite simply, one of the most important educational games ever made. 🏆 ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Score: 9.5 / 10 (A landmark achievement in non-traditional gameplay and targeted learning. The only losses are for:** the slightly limited sound quality (Feibel.de’s point), the absence of very basic verbal instructions for the hot-spots that the youngest players might miss, and the purely commercial demo interruptions, which, while smart, are still marketing. The core experience is transcendent.)