- Release Year: 1990

- Platforms: DOS, Linux, Macintosh, Windows

- Developer: David Niecikowski, Jeff Mather

- Genre: Role-playing

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Procedurally generated dungeons, Roguelike

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 67/100

Description

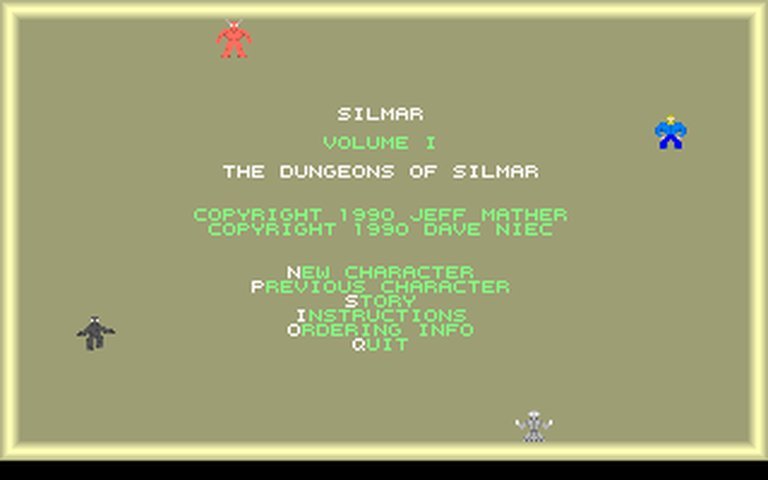

Silmar is a classic rogue-like RPG set in a fantasy world where players control an adventurer descending into randomly generated dungeons beneath the village of Silmarii, cleansing a cursed labyrinth left by the defeated evil wizard Syrilboltus after his war with the dwarf country Gormarundon. Featuring tile-based graphics in its original 1990 DOS shareware release (Volume I: The Dungeons of Silmar), players battle monsters, collect treasure, and use teleport beads to access village shops, with later ports and updates offering pixel graphics and expanded above-ground features.

Silmar Free Download

PC

Silmar Reviews & Reception

classicreload.com : a lesser-known gem in the realm of classic DOS games, captivating players with its simple yet engaging mechanics.

dosgames.com (60/100): decent graphics for a roguelike game, and a good option for players who don’t want to learn dozens of hotkeys.

Silmar: Review

Introduction

In the shadowy annals of early PC gaming, where pixelated peril lurks around every procedurally generated corner, few titles evoke the raw, unforgiving thrill of roguelikes quite like Silmar. Released in 1990 as a shareware darling on DOS, this top-down dungeon crawler invites brave adventurers to plumb the cursed depths beneath the fallen tower of the evil wizard Syrilboltus. Amid a sea of sprawling epics like Ultima and Might and Magic, Silmar stands as a minimalist masterpiece of risk and reward, its randomly generated labyrinths ensuring no two descents are alike. This review argues that Silmar is not merely a relic of the shareware era but a foundational roguelike that distills the genre’s addictive highs—exploration, brutal combat, and fleeting triumphs—into a compact, replayable package, cementing its quiet legacy as an underappreciated gem worthy of modern emulation.

Development History & Context

Silmar‘s origins trace back to a tiny team of indie visionaries: Jeff Mather and David Niecikowski, who copyrighted the DOS version in 1990. Operating in the wild west of shareware distribution—via bulletin board systems (BBS) and floppy disks—the duo crafted a game that epitomized the DIY ethos of early PC development. The original trilogy structure was a masterstroke of the shareware model: Volume I: The Dungeons of Silmar released freely to hook players, with An Everpresent Magic and The Forward Terminus unlocked upon registration (around $12). This mirrored contemporaries like Telengard or The Dungeons of Moria, capitalizing on the era’s exploding home computer market.

The 1990 gaming landscape was a fertile ground for roguelikes, building on pioneers like Rogue (1980) and NetHack (1987). DOS machines, with their 320×200 VGA resolutions and keyboard-only inputs, imposed severe constraints—no mouse support, limited colors (256 in VGA mode), and meager storage (the shareware episode clocks in at just 30-69 KB). Mather and Niecikowski leaned into tile-based graphics, prioritizing procedural generation over hand-crafted levels to maximize replayability on modest hardware. Fast-forward to 1999-2004’s v2.x ports for Windows, Linux, and Mac, and later v3.0 (2019-2020, Java-based and free with donations via dunjax.com), where Mather iterated with pixel art and expanded surface hubs. These updates reflect a solo passion project, open-sourcing the engine while preserving the core formula. In an age dominated by console RPGs like Dragon Quest, Silmar embodied PC gaming’s niche appeal: deep, solitary challenges for tinkerers unafraid of permadeath.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Silmar‘s story is a lean, archetypal fantasy yarn, delivered via terse intros and in-game flavor text, but it punches above its weight in thematic resonance. The inciting incident: the dwarf kingdom of Gormarundon vanquishes the archmage Syrilboltus in war, only for his dying curse to birth a monster-infested dungeon labyrinth beneath his razed tower, menacing the nearby village of Silmarii. Players inherit the mantle of countless failed heroes, tasked with delving to the nadir to “cleanse and seal” the peril. It’s classic high-fantasy boilerplate—evil wizard’s lingering spite—but laced with roguelike fatalism: every adventurer before you lies dead, their loot scattered as bait.

Character creation sets a whimsical tone amid the grimdark. The DOS original offers an eclectic roster—werewolves for feral might, pixies for nimble evasion, ninjas for stealth, even baseball players wielding bats as improvised clubs (“oh, the horror!” as one source quips). This eccentricity nods to NetHack‘s absurdity, subverting heroic tropes; your “gymnast” might flip through traps, while a minotaur charges blindly. Later versions streamline to a single human adventurer, emphasizing universality over novelty. Dialogue is sparse—NPC hints in the village shop, priestly blessings, or wizardly scrolls—but thematically potent: themes of hubris (Syrilboltus’s arrogance births eternal strife), greed (hoarding treasure rebuilds homelands), and resilience (gaining “powers” through XP mirrors personal growth). No branching plots or deep lore dumps; instead, emergent storytelling via permadeath runs fosters existential dread. Each death reinforces the theme: heroism is ephemeral, victory a razor-thin gamble, echoing Rogue‘s philosophical core.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its heart, Silmar is pure roguelike alchemy: procedural dungeons, turn-based combat, and survival loops refined to keyboard simplicity (press ‘H’ for controls). Core loop: select class, descend levels teeming with “hideous creatures,” battle for XP/treasure, teleport out via bead to the surface village for resupply, repeat until victory or doom. Dungeons randomize layouts, foes, and loot, ensuring infinite variety—walls, traps, hidden rooms demand meticulous mapping (mental or paper).

Combat is turn-based and tactical: enemies wield “various powers” (poison, paralysis?), forcing strategic positioning. Melee dominates early, evolving to spells/powers gained via progression. No complex AI, but escalating difficulty—deeper levels spawn deadlier beasts—demands adaptation. Progression shines: XP levels stats, unlocks abilities; inventory management (potions, weapons, armor) is key, with weight limits punishing overgreed. Teleport beads provide clutch escapes, but overuse risks stranding loot.

UI/Systems: Spartan brilliance. Top-down view displays tiles crisply; status bars track HP, mana, gold. Village hub evolves: original has basic shop; v2.x adds smithy (upgrades), priest (heals), wizard (scrolls), trader (sells loot), messenger (home storage). Flaws? Steep curve—no tutorials beyond hints; permadeath (implied, per roguelike norms) frustrates casuals. Innovations: class diversity sparks experimentation; shareware gating builds investment. Cheats/hints from emulators emphasize saving, NPC clues, build-testing—hallmarks of unforgiving design.

| Mechanic | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Exploration | Procedural infinity, secrets galore | No automap; easy to get lost |

| Combat | Turn-based depth, power variety | Predictable patterns post-familiarity |

| Progression | XP powers feel earned | RNG loot swings runs wildly |

| UI | Intuitive keys, uncluttered | Dated, no QoL like quicksave |

World-Building, Art & Sound

Silmar‘s world is a vertical slice of fantasy grit: surface Silmarii village as safe haven, subterranean hellscape of Syrilboltus’s curse. Atmosphere builds via isolation—cramped tiles evoke claustrophobia, random spawns heighten paranoia. No overworld travel; focus amplifies dungeon immersion, with treasures funding “homeland rebuilding” as vague motivation.

Art: DOS tiles are functional, evocative—monsters as blocky horrors, player sprites differentiated by class (werewolf fangs, baseball bat gleam). 320×200 resolution suits the era, with v2.x pixel upgrades adding fluidity. Screenshots reveal moody palettes: dim greens/blues for depths, warm hues topside.

Sound: Beeps and chiptunes (PC speaker limits)—stabs for hits, low rumbles for alerts. Sparse but effective; silence amplifies tension, combat chirps heighten urgency. Collectively, these forge nostalgia-drenched immersion, proving less-is-more in evoking dread and discovery.

Reception & Legacy

Launch reception was niche: shareware success via BBS, bundled in 1994’s 50 Great Games plus Knights of the Sky. No critic reviews on MobyGames (unranked), but players average 3.7/5 (5 ratings)—praise for challenge, gripes on difficulty. DOSGames.com awards 3/5: “decent graphics… quite difficult.” Commercial? Modest; shareware sales sustained ports.

Legacy endures via emulation (DOSBox, Archive.org) and Mather’s stewardship—v3.0 freeware (donations encouraged), Java ports broaden access. Influences Ancient Domains of Mystery, echoes in modern roguelikes (The Binding of Isaac‘s procedurals). Cult status grows: sites like ClassicReload hail it a “portal to the past,” akin to Rogue‘s forebears. In roguelike evolution—from ASCII Hack to pixel Spelunky—Silmar bridges eras, inspiring indie devs with its open-source engine and proof of small-team magic.

Conclusion

Silmar masterfully captures roguelike essence—random peril, strategic depth, bittersweet victories—in a shareware package that punched above 1990s constraints. Jeff Mather’s vision, from quirky classes to iterative ports, outshines minor UI foibles and sparse narrative. Neither revolutionary nor flawless, it earns a resounding 8/10 as essential roguelike history: download via Abandonware or dunjax.com, embrace the grind, and join the ghosts of Silmarii. In video game canon, Silmar resides among unsung heroes, a testament to PC gaming’s scrappy soul. Rediscover it; your next run might be the one.