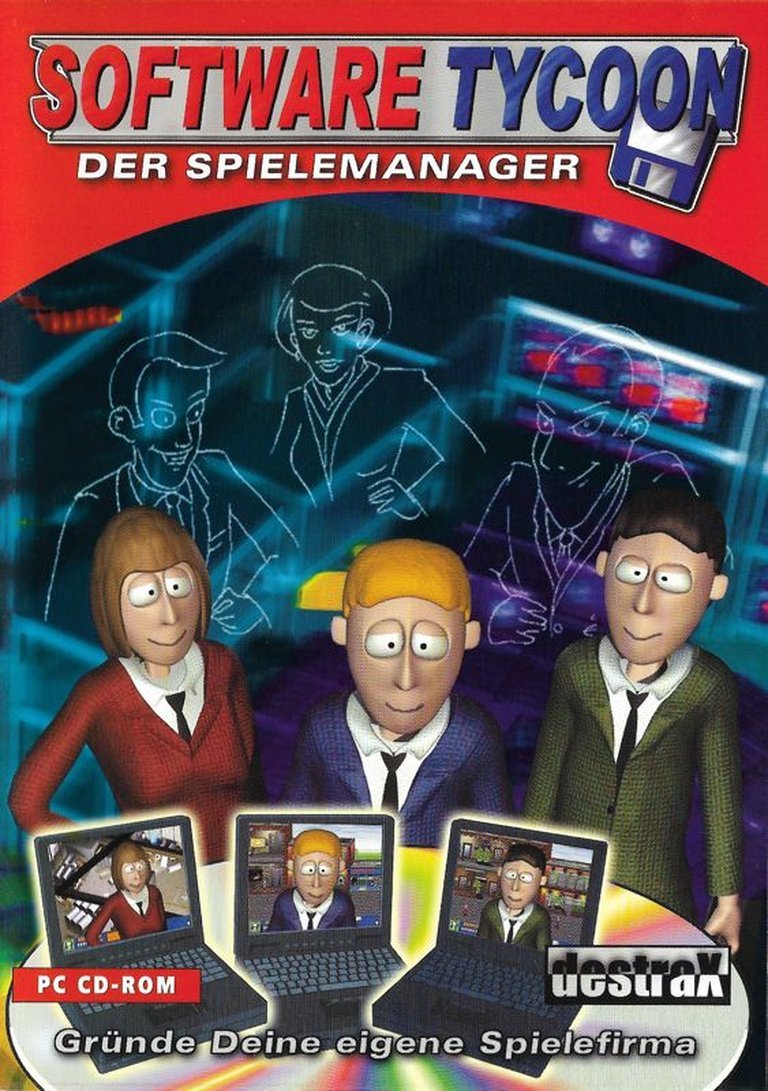

- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: Amiga, Linux, Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Blackstar Interactive GmbH, e.p.i.c. interactive entertainment gmbh, Linux Game Publishing Ltd.

- Developer: destraX Entertainment Software GbR

- Genre: Simulation, Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other), Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Business simulation, Managerial

- Setting: Game development

- Average Score: 75/100

Description

Software Tycoon: Der Spielemanager is a managerial business simulation game set in the early 1980s gaming industry, where players start a game development company with limited funds and must oversee all operations including designing concepts, hiring and assigning staff, researching graphics and genre technologies, acquiring movie licenses via auctions, producing, marketing, and selling games while monitoring sales charts, competitor stats, and magazine reviews to build reputation and achieve goals like winning ‘Game of the Year’ in scenario modes or free play.

Software Tycoon: Der Spielemanager Patches & Updates

Software Tycoon: Der Spielemanager Reviews & Reception

retro-replay.com : delivers a deeply engaging simulation of running a game development studio from the ground up.

Software Tycoon: Der Spielemanager: Review

Introduction

Imagine stepping into the shoes of a visionary entrepreneur in the nascent dawn of the home gaming era, armed with a modest stack of cash and big dreams of digital dominance. Software Tycoon: Der Spielemanager, released in 2001 by the small German studio destraX Entertainment Software GbR, invites players to do just that—managing a game development company from the early 1980s onward. This managerial simulation stands as one of the earliest dedicated “game-about-making-games” titles, predating modern hits like Game Dev Tycoon and Software Inc. by over a decade. Amid the pixelated boom of the post-Atari era, it captures the gritty realities of studio life with a satirical edge, blending economic strategy and creative oversight. My thesis: While hampered by technical limitations and repetitive loops reflective of its era, Software Tycoon earns its place as a pioneering artifact in business simulation gaming, laying foundational mechanics for the genre and inspiring direct successors like Mad Games Tycoon.

Development History & Context

Developed by destraX Entertainment Software GbR, a boutique German outfit led by brothers Christian and Stefan Pohl, Software Tycoon emerged from a creative core of just a handful of talents. Christian Pohl handled idea/concept, graphics, and sound; Stefan Pohl programmed and co-conceived the core idea alongside Sven Grochholski. Additional graphics came from Dennis Aufderheide and Soft Enterprises, with testing and management by figures like Simon Hellwig and Stefan Marcinek. Published primarily by Blackstar Interactive GmbH for Windows, it saw ports to Amiga and Macintosh in 2002, and Linux in 2005 via Linux Game Publishing Ltd., showcasing remarkable cross-platform ambition for a 2001 release.

The early 2000s PC gaming landscape was dominated by real-time strategy juggernauts like Age of Empires II and emerging tycoon sims such as RollerCoaster Tycoon, but game development simulations were rarities. Precursors like Software Manager (1994, Kaiko) and Software Star (1985) existed, yet Software Tycoon innovated by focusing explicitly on the “meta” theme of game dev itself. Technological constraints of the time—CD-ROM distribution, mouse-only input, and 2D side-view perspectives—shaped its clean, utilitarian interface, evoking 1980s business software aesthetics. The Pohls’ vision was prescient: set against the 1980s gaming renaissance (think Pac-Man fever to NES launch), it satirized industry pitfalls like tech leaps and hype cycles, all while navigating post-dot-com bubble economics that favored niche German titles. Published in Germany with a USK 0 rating (all ages), it bundled into packs like Totally Tycoon (2002), extending its reach amid a market shifting toward 3D spectacles.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

Software Tycoon eschews linear storytelling for emergent narrative, where your studio’s rise (or fall) crafts a personalized epic. There’s no scripted plot or voiced characters; instead, the “story” unfolds through in-game events, sales charts, and abstract magazine reviews. You begin as a scrappy founder in 1981-ish, bootstrapping with limited funds, mirroring real-world pioneers like those at Activision or Electronic Arts during the 1983 crash recovery.

Themes revolve around capitalism’s double-edged sword: innovation versus exploitation, hype versus quality. Researching from 4-color to 256-color graphics symbolizes the graphical arms race from Pong to Doom. Auctioning movie licenses evokes Hollywood tie-in mania (E.T. fiasco included?), while competitor tracking highlights cutthroat rivalry. Reputation mechanics tie into themes of legacy—flops tank morale and cash, hits unlock elite hires, creating dramatic arcs of rags-to-riches or hubris-fueled bankruptcy.

Scenarios provide loose “chapters,” like engineering a “Game of the Year” winner, forcing tense decisions: rush a low-fi arcade title or invest in groundbreaking genres? Free-style mode allows sandbox tales, such as dominating with edutainment before pivoting to warfare sims. Dialogue is minimal—functional tooltips and review blurbs—but satirical, poking fun at industry tropes (e.g., “outdated sound drags down potential”). No deep characters exist; employees are skill-rated assets, yet assigning tasks humanizes them, evoking the grind of crunch time. Ultimately, the narrative critiques the dream factory: success demands ruthless efficiency, but repetition underscores burnout’s monotony.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, Software Tycoon delivers a meticulous business simulation loop: plan, execute, iterate. Start by designing concepts—selecting genres (arcade to emerging puzzles/sports), tech levels, and licenses via tense auctions. Hire specialists (programmers, artists, sound designers) from a pool, assigning granular tasks to projects. Production covers packaging (custom boxes/posters) and marketing budgets, culminating in releases to an in-game shop.

Key Systems:

– Research Tree: Allocate funds to upgrades (e.g., 4- to 256-color graphics, new genres), a tech tree balancing short-term projects against long-term edges. Delays here create strategic tension.

– Sales & Feedback: Set prices dynamically, monitor monthly/all-time charts (rivals included), and parse auto-generated reviews rating graphics/sound/gameplay. Reputation snowballs: hits attract talent, flops spiral debt.

– Modes: Scenarios impose goals (e.g., GOTY award); free-style offers endless empire-building. Single-player only, mouse-driven, 1st-person managerial view with side-view elements.

– UI/Progression: Clean panels for departments (design/programming/art/marketing) track progress via charts. No traditional leveling—progression is economic (expand office, hire more).

Innovations shine in micromanagement depth—task allocation feels authentic—but flaws abound: no parallel projects (one game at a time), glacial dev cycles (250+ days), and repetition post-initial hits. Critics noted fun evaporates as routines loop, lacking depth in staff morale or events. Still, risk-reward (overbid on license? Cut corners?) yields addictive highs, proto-Game Dev Tycoon.

| Mechanic | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Hiring/Assignment | Granular control | No morale/fatigue |

| Research/Auctions | Strategic foresight | Long wait times |

| Sales/Reviews | Real-time feedback | Predictable after mastery |

| Modes | Replayable variety | Scenarios too linear |

World-Building, Art & Sound

The “world” is a abstracted 1980s-90s game industry microcosm: no explorable map, but immersive via simulated markets. Shop charts mimic Computer Gaming World top-sellers; rivals’ releases foster paranoia. Period authenticity—starting with edutainment/arcade, evolving to racing/warfare—builds nostalgic atmosphere, reinforced by retro tech progression.

Art Direction: Functional 2D pixel art with clean, era-appropriate UI. Crisp charts, icon menus, and subtle animations (disc printing, billboard updates) prioritize readability. Packaging customization adds flair, but overall “not zeitgemäß” (outdated), per reviews—blocky sprites evoke 8-bit tools without flash.

Sound Design: Christian Pohl’s chiptunes and effects (bleeps, whirs, “cha-ching” sales) nail 1980s nostalgia, but critics slammed it as subpar. Minimalist score loops underscore tedium productively, enhancing sim immersion without distraction. Together, elements craft a cozy, spreadsheet-like vibe—charming for historians, bland for casuals—perfectly suiting the tycoon ethos.

Reception & Legacy

Launch reception was middling: MobyGames aggregates 55% critics (Amiga’s Obligement 70%: “original concept, solid realization”; Windows averaged 52%, with PC Games 31% blasting repetition, PC Action 67% praising satire). Players rated 2.3/5 (sparse data). German mags like GameStar (54%) lauded ideas but decried waits/sound/UI.

Commercially niche, it faded amid 2001’s GTA III hype, yet ports (Amiga/Mac/Linux) extended life. Legacy endures: directly inspired Mad Games Tycoon (2012, Eggcode) by Stefan/Christian Pohl—deeper mechanics, same spirit. Echoes in Software Inc. (2015), Game Dev Studio. As a “game dev tycoon” pioneer post-Software Manager, it influenced meta-sims, preserving 1980s industry lore. Collected by few (8 Moby users), abandonware status aids preservation, with fans clamoring for GOG ports.

Conclusion

Software Tycoon: Der Spielemanager is a flawed gem—a 6.1/10 snapshot of ambition constrained by 2001 tech, where initial thrills yield to repetition and austerity. Yet its exhaustive systems, emergent tales, and prescient theme cement it as essential history: the ur-text for game dev sims. For tycoon aficionados or retro enthusiasts, it’s a must-play relic; casuals may bail early. Definitive verdict: Pioneering B-Tier Classic—influential blueprint deserving emulation and revival in video game history’s annals.