- Release Year: 2012

- Platforms: Android, iPhone, Windows

- Publisher: Big Fish Games, Inc, S.A.D. Software Vertriebs- und Produktions GmbH, Specialbit Studio

- Developer: Specialbit Studio

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Hidden object, Mini-games, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Detective, Horror, Mystery

- Average Score: 50/100

Description

Sonya: The Great Adventure is an adventure game that blends hidden object searches, mini-games, and puzzle-solving with a detective and horror narrative. Set in a first-person, fixed flip-screen visual style, players explore mysterious environments to uncover clues and unravel a suspenseful story.

Where to Buy Sonya

PC

Sonya Guides & Walkthroughs

Sonya Reviews & Reception

flyingomelette.com (50/100): Though it’s a finely-crafted game, the story feels like it was weaved in as an afterthought.

judsgamereviews.wordpress.com : So despite the lack of guidance it is really good if a little taxing at times.

saveorquit.com : Sonya: The Great Adventure is competent, but no more than that.

Sonya: The Great Adventure – A Review

Introduction

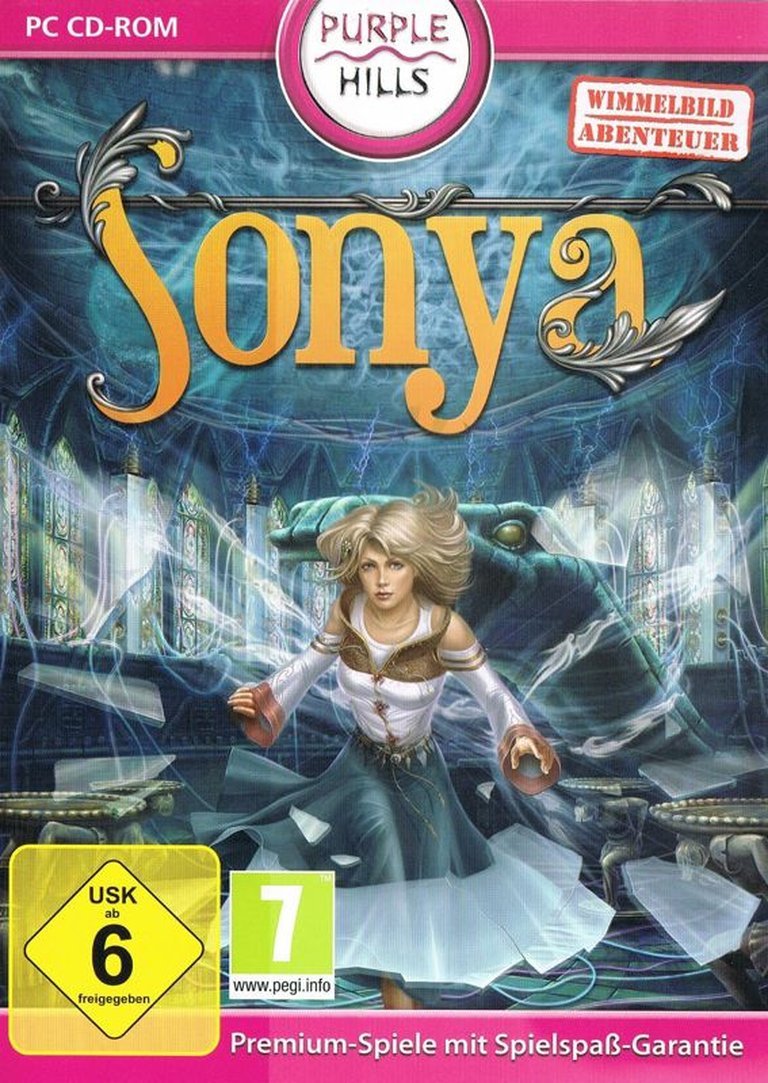

In the bustling landscape of 2012’s casual and indie gaming market, one title that flew largely under the radar was Sonya: The Great Adventure (also known simply as Sonya), a hidden object puzzle adventure (HOPA) from Russian developer Specialbit Studio. Released for Windows in February 2012 and later ported to mobile platforms, Sonya represents a classic, mid-era entry in the hidden object genre—a period saturated with titles from Big Fish Games and other publishers vying for the attention of puzzle enthusiasts. Unlike the critically adored, genre-defining masterpiece Journey that also debuted in 2012, Sonya did not seek to evoke transcendental emotion or innovate on multiplayer interaction. Instead, it aimed to deliver a solid, if formulaic, fantasy-themed adventure with a focus on item hunts, inventory puzzles, and a story of sibling rescue. This review will dissect Sonya on its own terms, examining its place within the HOPA genre of its time, its mechanical execution, narrative coherence, and why it remains a footnote rather than a landmark in gaming history. My thesis is that Sonya is a competently constructed but deeply generic example of its genre, whose lack of distinctive identity, narrative depth, and technical ambition rendered it instantly forgettable against both its contemporaries and the year’s more celebrated releases.

Development History & Context

Sonya was developed by Specialbit Studio, a lesser-known Russian studio whose portfolio, as glimpsed on MobyGames, consists primarily of other casual adventure and hidden object games such as Inbetween Land, Haunted Hotel: Charles Dexter Ward, and Island: The Lost Medallion. The game was published in the West by S.A.D. Software (a German publisher) and major casual distributor Big Fish Games. The development context is sparsely documented, but the game’s structure and the credits (listing roles like Product Manager, Scenario, and Game Design) suggest a small, focused team working within the well-established production pipeline of the mid-2000s/early-2010s casual game industry.

Technologically, Sonya was built for the PC (Windows) using what was likely a proprietary or licensed 2D engine common to HOPAs of the era. Its visual style—pre-rendered, detailed, fixed-perspective backgrounds—was the industry standard, competing directly with the output of studios like Artifex Mundi, Blue Tea Games, and Boomzap Entertainment. The game’s release in early 2012 places it in a transitional period for digital distribution; it was a commercial title sold via platforms like Steam ($6.99) and Big Fish Games, leveraging the “try before you buy” demo model that was crucial for casual game sales.

The gaming landscape of 2012 was dominated by blockbuster AAA titles like Mass Effect 3, The Last of Us, and Dishonored. However, the digital storefronts (PlayStation Network, Xbox Live Arcade, Steam) also saw a thriving indie and casual scene. It was the year Journey would redefine artistic ambition in digital games, while Sonya embodied the more pragmatic, commercially-oriented side of that same digital marketplace. Against such formidable competition, Sonya’s lack of a unique hook or marketing push ensured it would be lost in the noise, a quiet entry in Big Fish’s vast library.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The narrative of Sonya is a straightforward, high-concept fantasy: the protagonist’s sister, Lily, has her life force stolen by “unknown villains,” leaving her in a comatose state. Sonya must embark on a “great adventure” to restore it. The plot is delivered through sparse dialogue boxes, a diary system that updates with story beats, and brief, comic-book style cutscenes that are stylistically jarring compared to the main game’s visuals.

The story’s primary weakness is its utter lack of exposition or world-building. As noted in the Flying Omelette review, the setting is an incoherent “mishmash of modern, Victorian, and fantasy” with no name or internal logic. Who are the villains? Why a life force? What is the nature of this world? The game never answers these questions. The motivation is purely functional (save sister), and the antagonists are faceless, malevolent forces encountered only as environmental obstacles (e.g., a soul-stealing orb, a wolf guarding cubs, puzzles in a “Weather Hall”). The “twist” or deeper revelation is absent; the journey is a series of connected fetch quests culminating in a confrontation with the source of the stolen life force and a brief reunion.

Thematically, the game gestured toward classic adventure and fairy tale motifs—a hero’s journey, magical transformation, overcoming trials—but lacks the intentionality or depth to explore them. The symbols (orbs, statues, keys) have no allegorical weight. The sister’s plight is a MacGuffin. Compared to the deliberate, monomyth-inspired emptiness of Journey’s protagonist, Sonya is a character with no discernible personality, beliefs, or arc. Her emotional journey is not the player’s; it is a stated objective. The narrative serves solely to patch together the puzzle locations, making it the thinnest possible scaffold for the gameplay.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Sonya is a quintessential hidden object puzzle adventure (HOPA). Its core loop is:

1. Explore a static scene in first-person, fixed-perspective view.

2. Find hidden objects from a list (standard HOS) or fragmented pieces to assemble.

3. Use collected items on scene hotspots (gear cursor) or within inventory puzzles (combine items).

4. Solve standalone puzzles (pipe rotation, wire matching, tile-sliding, constellation mapping) to unlock new areas or progress the story.

5. Repeat across a linear series of chapters/locations.

The gameplay is broken into four main chapters: “Lily” (the house and initial magical awakening), “The Forest Man” (a giant tree with themed rooms), “The Portal” (a transitional area with animal interactions), and “Weather Hall” (a final puzzle-focused mansion). A bonus “Collector’s Edition” chapter involves repairing an airplane.

Strengths:

* Puzzle Variety: The game offers a commendable diversity of puzzles, many integrated logically into the environments (e.g., fixing a telescope to see clues, using a magnet to retrieve keys). The “tree house” chapter, with its seven themed rooms (musician, hunter, artist, etc.), is a clever design, requiring players to use items from one room in another, creating a satisfying web of dependencies.

* Hint System: The red locket hint system is functional, though it recharges slowly, encouraging careful searching.

* Pacing: For a genre often criticized for padding, Sonya’s chapter structure provides a clear sense of progression. The puzzles are generally medium difficulty and do not egregiously rely on “pixel hunting” due to the clear hand/gear/eye cursors.

Weaknesses & Flaws:

* The “Cat’s Cradle” Puzzle: The Flying Omelette review explicitly calls out one puzzle as “the most aggravating Cat’s Cradle puzzle I’ve ever seen,” indicating a particularly obtuse and frustrating design outlier.

* Backtracking & No Map: This is the game’s most significant flaw. As Jud’s review states, “There is NO Map!” Players must constantly traverse between dozens of locations to use newly acquired items, often passing through multiple empty screens. This creates significant fatigue and feels like unnecessary padding, a common issue in older HOPAs but one that Sonya exemplifies without mitigation.

* Lack of Journaling: While a diary exists for story updates, it does not automatically log puzzle clues or important information, forcing players to rely on memory or external note-taking for complex multi-location puzzles (e.g., the constellation puzzle requiring telescope observation and later application).

* Generic Mechanics: There is no innovation. The mechanics are pulled directly from the HOPA playbook of 2005-2012. The “magic” element (orbs that must be “loaded” by solving puzzles) is a thin veneer on standard key-finding.

* Aggravating Skippable Puzzles: Both reviews mention having to skip a couple of puzzles that “wouldn’t finish when I’d completed them,” pointing to potential bugs or unclear success conditions, a critical failure in a puzzle-focused game.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Sonya’s world is its most contradictory element. On one hand, the visual art is often praised. The backgrounds, while dated by today’s standards, are “gorgeous,” “colourful, detailed, and in places really ornate” (Jud’s review). There is a clear effort to create distinct, atmospheric environments: a cozy cottage, a mystical giant tree, a stormy weather observatory. The attention to detail in the static scenes is a hallmark of the genre at its best.

However, this artistic effort is sabotaged by inconsistency and poor integration. The comic-book style cutscenes are “hand-drawn” but clash aesthetically with the painted backgrounds, appearing cheaper and less polished. Sonya’s dialogue portrait is in yet another style, closer to the main game but still disconnected from the cutscenes. This lack of a unified visual identity undermines the sense of a cohesive world. The setting, as noted, is a confused blend of aesthetics with no cultural or tonal through-line.

The sound design is functional but unremarkable. The Jud’s review notes the music is “really good” but turned down—a common player behavior for casual game soundtracks that are pleasant but not integral to the experience. There are no voice-overs, only text. The audio serves as ambiance, not storytelling.

Ultimately, the world-building fails because the art and narrative are divorced. The beautiful scenes have no narrative weight; the story provides no context for the beauty. The player is a tourist in a series of pretty, disconnected rooms, not an inhabitant of a lived-in space. This is the antithesis of the environmental storytelling in Journey, where every grain of sand and ruin contributes to a silent, profound narrative.

Reception & Legacy

Sonya exists in the vast, uncritical catalog of casual games. It received no major critic reviews from outlets like IGN, GameSpot, or Eurogamer; the MobyGames review section is empty. Its reception is filtered solely through player reviews on sites like Big Fish Games and niche HOPA blogs.

The two available professional-ish reviews (Flying Omelette, Jud’s PC Game Reviews) are lukewarm:

* Flying Omelette (2011): Score 2.5/5. Calls it a “rather decent oldschool HOG” but heavily criticizes the story as an afterthought, the title as lackluster, and the narrative incoherence. It concludes the game’s appeal is purely functional: “if the game itself sounds inviting… a free demo is available.”

* Jud’s PC Game Reviews (2017): A retrospective replay. More positive, awarding roughly 4 stars (out of a perceived 5). Praises the graphics, puzzle variety, and satisfaction of completion, but reiterates the “NO Map!” frustration and the lack of guidance as a “frustration factor.” The bonus chapter is noted as substantial.

Commercially, its presence on Steam and Big Fish Games suggests it sold modestly within its niche. It was likely a profitable, low-risk project for Specialbit Studio and Big Fish, fitting their model of regular, reliable content output. It did not break sales records, win awards, or spark any community discourse.

Its legacy is virtually non-existent. It is not cited in discussions of the hidden object genre’s evolution. It did not influence other developers. It is not remembered by players outside of those who specifically seek out “old-school HOPAs.” In 2012, the same year Journey was redefining what a game could be emotionally, Sonya represented the unchanging, stagnation-prone casual game paradigm: competent craft without ambition, reliant on a formula being slowly eclipsed by more sophisticated narrative and design approaches even within its own genre (e.g., Mystery Case Files beginning to experiment more).

Conclusion

Sonya: The Great Adventure is a perfectly serviceable, ultimately forgettable hidden object puzzle adventure. It delivers exactly what its packaging promises: a fantasy quest with item hunts and puzzles spread over several picturesque locations. Its assets—the detailed backgrounds, the varied puzzles, the functional core loop—are competently executed and would have satisfied a player in 2008. But by 2012, with the bar for casual game production values and narrative integration rising, Sonya feels dated and uninspired.

Its fatal flaw is not any single broken mechanic, but a profound lack of identity. It has no distinctive art style, no compelling story, no innovative system, and no memorable moment. It is the gaming equivalent of a generic paperback fantasy novel—readable, inoffensive, but instantly forgettable. In a year that gave us the profound, wordless pilgrimage of Journey, Sonya highlights the vast chasm between games that use genre conventions to transcend them and those that merely replicate them. For historians, Sonya is a data point: evidence of the mass-market, assembly-line approach to casual adventure games that dominated digital storefronts in the early 2010s. For players, it is a time capsule of a simpler, less demanding era of puzzle gaming, best experienced with a walkthrough handy to mitigate its greatest sin: the soul-crushing absence of a map.

Final Verdict: 6/10 – Competent genre fare, but obsolete upon release. Play only if you have a specific nostalgic craving for mid-2000s HOPAs and possess the patience for exhaustive backtracking.