- Release Year: 1978

- Platforms: Antstream, Atari 2600, Windows, Xbox 360

- Publisher: Atari, Inc., Atari Interactive, Inc., Microsoft Corporation, Sears, Roebuck and Co.

- Developer: Atari, Inc.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Hotseat, Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Docking, Gravity, Hyperspace, Momentum-based, Resource Management, Shooter

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

Description

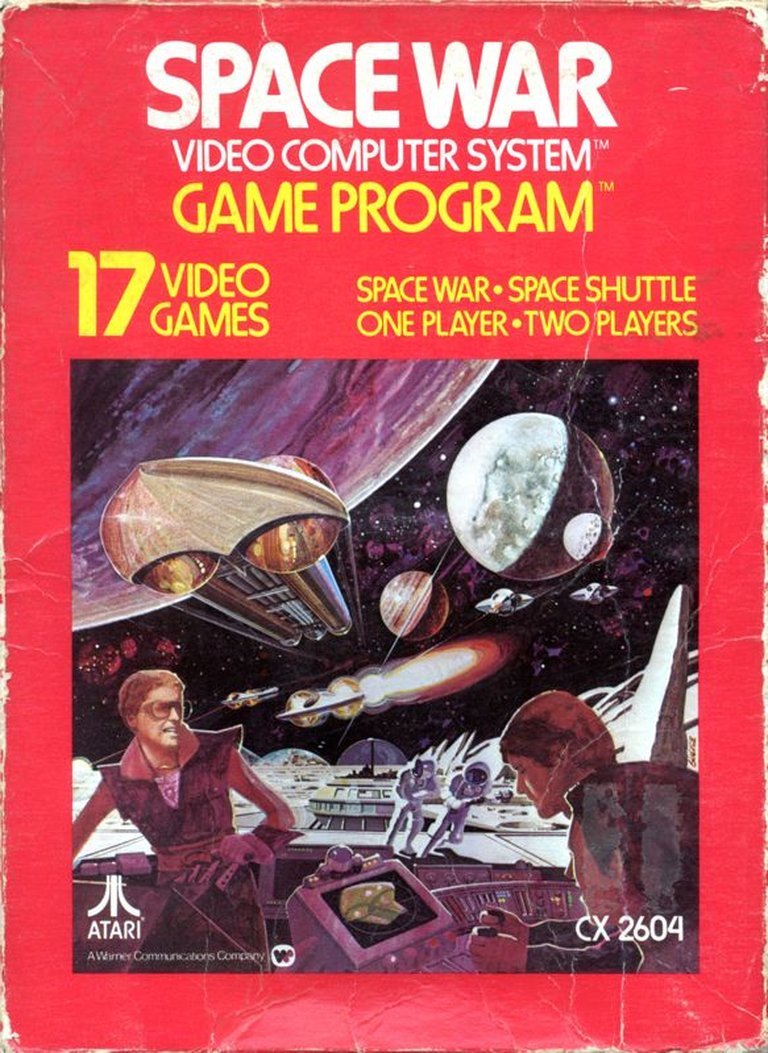

Space War, released in 1978 for the Atari 2600, is a pioneering home adaptation of the classic mainframe game Spacewar!. It features two modes: Space War, where two players duel in spaceships with momentum-based controls, limited fuel and ammunition, and variants involving screen boundaries, hyperspace jumps, a gravitational sun, and a resupply starbase; and Space Shuttle, a docking simulation playable solo or cooperatively, requiring precise maneuvers to connect with moving modules. Set in a top-down sci-fi space environment, the game emphasizes physics-oriented gameplay and strategic resource management, with matches concluding after 10 minutes or when a player reaches 10 points.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Space War

PC

Space War Free Download

PC

Space War Guides & Walkthroughs

Space War: A Historical Review of Atari’s 2600 Adaptation of Gaming’s Ancestor

Introduction: The Weight of Legacy on a Cartridge

To speak of Space War for the Atari 2600 is to speak in the shadow of a giant. This 1978 cartridge, developed by Ian Shepherd and published by Atari, Inc., is not merely another entry in the fledgling console’s library. It is a direct, albeit greatly simplified, descendant of Spacewar!—the 1962 PDP-1 mainframe game widely regarded as the first true video game. As such, Space War exists in a unique historical limbo: it is simultaneously a commercial product of its time and a conscious, programmed echo of the very dawn of interactive electronic entertainment. This review will argue that while Space War is a historically significant document—a crucial link in the chain connecting academic mainframes to the living room—it is, by almost any contemporary or modern metric, a flawed and often tedious game. Its value lies not in its playability, but in what it represents: the attempt to domesticate a revolutionary, community-forged idea for a mass market still learning what video games could be. It is a translation of a sacred text into a simpler language, losing some poetry in the process but ensuring the story was told far and wide.

Development History & Context: From MIT Kludge Room to the VCS

The Genesis of an Idea: Spacewar! (1962)

The story must begin with its source. In early 1962, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a group of programmers—most notably Steve Russell, Martin Graetz, and Wayne Wiitanen—created Spacewar! for the DEC PDP-1 minicomputer. It was a product of the “hacker ethic”: a collaborative, open-source effort designed to showcase the machine’s real-time graphical capabilities. The game featured two monochrome spaceships (“the needle” and “the wedge”) engaged in a dogfight within the gravity well of a central star. Its mechanics were revolutionary: Newtonian physics (inertia, momentum), limited fuel and ammunition, a strategic hyperspace “panic button,” and a starfield backdrop that later evolved into Peter Samson’s meticulously plotted “Expensive Planetarium.” Crucially, it was a fiercely competitive two-player experience born in an academic environment where the computer itself was a rare, shared resource.

The Commercial Catalysts: Computer Space and Space Wars

Spacewar! remained confined to research labs and universities for nearly a decade, but its legend spread. It directly inspired the first commercial arcade games: the cumbersome Galaxy Game (1971) and the more famous Computer Space (1971), created by Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney. While Computer Space was a commercial disappointment due to its complexity, it proved the concept had market potential. The more successful vector-graphics arcade game Space Wars (1977), designed by Larry Rosenthal, refined the formula with adjustable variables (gravity strength, black hole vs. destructive sun) and became a hit, selling over 7,000 units. This 1977 arcade resurgence is the most immediate precursor to Atari’s home version.

Atari’s Adaptation: Ian Shepherd and the 1978 VCS

By 1978, Atari’s Video Computer System (VCS) was a success, but its developers had mined most of the obvious arcade licenses. To fill the holiday catalog, they looked backward, not forward. Programmer Ian Shepherd (credited simply as “Ian Shepard” in the game’s credits) was tasked with porting the essence of Spacewar! to the severely limited VCS hardware. This was a monumental challenge. The VCS had a 1.19 MHz CPU, 128 bytes of RAM, and a custom graphics chip that displayed only basic geometric shapes on a 160×192 pixel screen. There was no way to simulate the precise gravity calculations or smooth vector graphics of the PDP-1 or Space Wars arcade cabinet.

Shepherd’s solution was radical simplification. He stripped the game to its absolute core: two triangular ships, basic thrust/rotation controls, and projectile firing. The complex gravity well was made optional and, as noted by the Atari Archive, its effect in the VCS version is “negligible or nonexistent,” reducing a central strategic pillar to a minor hazard. The hyperspace function was reimagined as a fuel-intensive cloaking device rather than a risky random teleport. Most significantly, he introduced an entirely new, non-combat mode: Space Shuttle, which tasked players with docking with a moving module—a unique addition that reflected the era’s fascination with NASA’s Space Shuttle program but bore little relation to the original’s dogfight精神.

The game was announced as “Starship II” at the January 1978 CES but rebranded Space War by April. It shipped in October 1978, packaged with a manual containing diagrams to explain the unintuitive momentum-based controls—a clear sign Atari knew its learning curve was steep.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Absence of Story, the Presence of Principle

Space War for the VCS is a pure mechanics-first experience. There is no narrative, no characters, no dialogue, and no explicit theme beyond the cold, abstract statement of its rules. This is both its greatest strength as a descendant of Spacewar! and its most significant limitation as a standalone experience.

The Theme of Pure Competition: The game’s entire context is adversarial. The “plot” is the match itself: a timeless, silent duel in a void. This mirrors the original Spacewar!, which was less about storytelling and more about creating a structured, skill-based conflict. The theme is implicitly Newtonian physics and resource management—every action has a reaction, and every shot and boost is a finite investment. The Space Shuttle mode introduces a theme of precision and cooperation (in two-player mode), but it feels tacked-on and lacks the visceral tension of combat.

Contrast with Source Material: The original Spacewar! was steeped in the pulp science fiction of its creators—the Lensman and Buck Rogers serials. Its ships were designed from rocket schematics, and the starfield was a real astronomical chart. This gave it a thematic weight that the VCS version, with its crude triangles and black void, completely discards. The Atari version exists in a purely abstract, geometric space. The “narrative” is solely in the player’s mind and the immediate tactical situation.

Dialogue and Character: There is none. The ships are anonymous vessels. The only “personality” comes from the player’s relationship with the controls and the predictable, bouncing movements of their opponent. This anonymity makes it a perfect, universalizable template for later games (like Asteroids or Star Control) to overlay with their own settings and lore.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Momentum, Variants, and a Missing Heart

The core of Space War is its two distinct, toggle-heavy game modes, each with multiple variants.

1. Space War (Combat Mode):

* Core Loop: Two players (no AI opponent) control ships on a fixed-screen arena. The goal is to score 10 points by hitting the opponent with a missile.

* Controls & Physics: The iconic “Asteroids-style” control scheme: Up for forward thrust (applying velocity in the ship’s facing direction), Left/Right to rotate the ship, Down for hyperspace (if enabled), and the fire button to launch a single missile. The critical mechanic is inertia. The ship does not stop when you release the thrust; it continues drifting. Braking requires thrusting in the opposite direction, consuming precious fuel.

* Resources: Each ship starts with 8 missiles and a limited fuel tank. Crucially, ammunition is only automatically reloaded when BOTH players are out of shots. This creates tense standoffs where players must conserve ammo or risk becoming helpless while the opponent resupplies. Fuel is only consumed by thrusting and hyperspace.

* Variants (7 options): These toggle:

* Boundary: Solid (ships/missiles bounce) or Wraparound (exit one side, enter opposite).

* Sun: On/Off. If on, a central star exert’s gravitational pull and destroys on contact (awarding the opponent a point).

* Starbase: On/Off. A stationary element that restores all fuel and ammo on contact.

* Hyperspace: On/Off. The “Down” command makes the ship vanish and reappear randomly, costing significant fuel.

* Strategic Depth (or Lack Thereof): In variants without a strong sun, the game devolves into a simple “line up your shot” contest. The limited ammo mechanic adds tension, but the automatic reload condition often leads to awkward pauses. The sun’s gravity is the only element that introduces meaningful strategic navigation—using it for slingshot maneuvers—but on the VCS, its pull is too weak to enable the complex orbital ballet of the original Spacewar!. As the Atari Archive notes, this removes “a lot of the strategy.”

2. Space Shuttle (Docking Mode):

* Core Loop: One or two players must dock their ship with a fast-moving “space module.” A successful dock awards a point.

* Mechanics: Fuel is unlimited here. The challenge is matching the module’s exact speed and vector. The difficulty switch can be flipped to require perfect angle matching as well. Docking affects the module’s trajectory, potentially making it faster and harder to catch.

* Variants (10 options): Toggle number of players (1 or 2), boundary type, sun presence, and module count (1 shared or 2 color-coded).

* Assessment: This mode is widely panned in contemporary reviews (e.g., Woodgrain Wonderland’s “lousiness”) and for good reason. It is a test of patient, frustrating calibration rather than dynamic skill. The module’s movement is erratic and unforgiving. It feels like a separate, less compelling mini-game grafted on to increase cartridge content. It lacks the immediate feedback and thrill of combat.

Overall Systems Flaws:

* No AI: Pure 2-player only. The “single-player” experience in Space Shuttle is just practicing against a clock, which is dull.

* Opaque UI: No on-screen score display is mentioned in the manual; players must remember the score or use an external notepad. Critical information like remaining fuel or ammo is absent.

* Control Learning Curve: As RobinHud’s review states, “it takes a little while to get used to the controls.” The inertia model is brilliant but punishing for newcomers.

* Pacing: Matches are either frantic, chaotic dogfights or slow, methodical (and frustrating) docking attempts. There’s little middle ground.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Aesthetics of Limitation

Space War presents a world of stark, minimalist abstraction.

* Visuals: The screen is a flat, single-color (likely black or very dark blue) background. The player’s ship is a simple triangle (or, in some variants, a slightly different shape). The opponent is an identical triangle in a different color. Missiles are small dots or dashes. The “sun” is a static circle. The “starbase” is a small square or cross. The “space module” in shuttle mode is a slightly larger, different-shaped sprite. There is no parallax, no scrolling, and minimal animation. The only sense of depth or motion comes from the ships’ movement and the trails they sometimes leave. This is not a game about immersive simulation; it’s about clean, readable geometry. The manual’s diagrams are more evocative than the on-screen graphics.

* Sound: The audio is quintessential early Atari 2600: a handful of piercing, simple beeps and boops. Thrust is a continuous low hum, firing is a sharp “pew,” hyperspace is a warping sound, and a hit or crash is a crashing noise. There is no melody, no ambiance, and very little dynamic range. It is functionally informative and utterly non-atmospheric.

* Contribution to Experience: The minimalist art and sound force the player’s focus entirely onto the abstract mechanics. There is no distraction, no “world” to get lost in—only the pure, unadorned interplay of shapes and physics. This aligns perfectly with the academic, diagrammatic spirit of the original Spacewar!, but for a 1978 consumer, it felt archaic and cheap next to the more detailed, character-driven games like Combat or Air Raid.

Reception & Legacy: A Footnote in Its Own Story

Contemporary Reception (1978-1980)

Space War was not a hit.

* Critical: The available critic scores are abysmal (33% average on MobyGames). The Video Game Critic called it “uninspired” and “one of Atari’s first discontinued titles,” noting its “minimal graphics” and that Combat offered “similar gameplay with more variety and more fun.” Woodgrain Wonderland’s “C” grade conceded the two-player fun but slammed the shuttle modes.

* Commercial: Its discontinuation by 1980, followed by a small re-release in 1982 and a minor sales bump in 1987, indicates it was a shelf-warmer. It was bundled with other minor titles in discount promotions, signaling Atari’s own assessment of its secondary status.

* Player: Modern retro player scores (1.8/5) and reviews echo the critics: fun in short bursts with a friend, marred by poor graphics, sound, and a steep control curve. The consensus is that it’s a historical curiosity, not a beloved classic.

Historical Legacy and Influence

This is where Space War‘s importance transcends its quality.

1. Direct Lineage: It is the first official home console adaptation of Spacewar!, bringing the game’s concepts—momentum-based space combat, limited resources—to a mass audience, however small. It predates and likely influenced the control scheme of Asteroids (1979), which Ed Logg has acknowledged was inspired by Spacewar!. The ship shape in Asteroids is a direct descendant.

2. Genealogy of Genres: The “Space War” template—two-player, physics-based, resource-managed dogfighting—is the foundational blueprint for:

* Vector arcade games like Space Wars (1977) and the Vectrex port.

* The ship-versus-ship combat in the landmark Star Control (1990) and Star Control II (1992), which explicitly cite Spacewar! as their inspiration.

* The core loop of countless space combat sims and top-down shooters.

3. Preservation of the Canon: As a commercial cartridge, Space War served as a time capsule. When later generations of historians and programmers sought out the origins of their medium, this was one of the tangible, owned artifacts linking them back to the PDP-1. Its re-releases in collections like Atari Flashback Classics and Atari Vault ensure its continued availability as a historical document.

4. A Lesson in Adaptation: It demonstrates the painful but necessary compromises of bringing a complex, academic, two-player-only experience to a 1978 home console aimed at children and families. The dilution of the gravity mechanic and the addition of the shuttle mode are recognizable acts of “dumbing down” for accessibility and content length.

Conclusion: A Flawed Vessel, an Essential Relic

For a professional game historian, Space War on the Atari 2600 is an indispensable object of study. It is the bridge between the closed, communal world of the 1960s computer lab and the commercial, domestic world of the late 1970s video game boom. Its development history is a masterclass in source material adaptation under severe constraints. Its gameplay mechanics, while notoriously difficult and often unsatisfying, preserve the core feeling of Newtonian flight that defined its ancestor.

However, as a game—as a piece of interactive entertainment judged by its own merits—it is deeply flawed. The minimalist art and sound are forgivable as period limitations, but the crippling lack of a single-player mode, the often-frustrating Space Shuttle variant, the muted impact of its most important strategic element (the sun’s gravity), and the obtuse lack of in-game feedback make it a hard sell for anyone not motivated by historical curiosity.

Its place in video game history is secure, not as a masterpiece, but as a vital signpost. It is the faint but clear watermark of Spacewar! transferred onto the North American console market. It proves that even a diluted, commercially awkward translation can carry the genetic code of an revolutionary idea. To play Space War today is not to enjoy a lost classic, but to perform a small act of archaeology—to feel the ghost of inertial thrust and hear the echo of a PDP-1’s beep in the crude blips of an Atari 2600. Its final verdict is this: a historically essential cartridge and a forgettable game. Its legacy is not in the hours of fun it provided, but in the unbroken chain of inspiration it represents, linking the first sparks of code to the sprawling, complex industry that followed.

Final Score (as a Historical Artifact): 9/10

Final Score (as a Game): 3/10