- Release Year: 2005

- Platforms: Windows

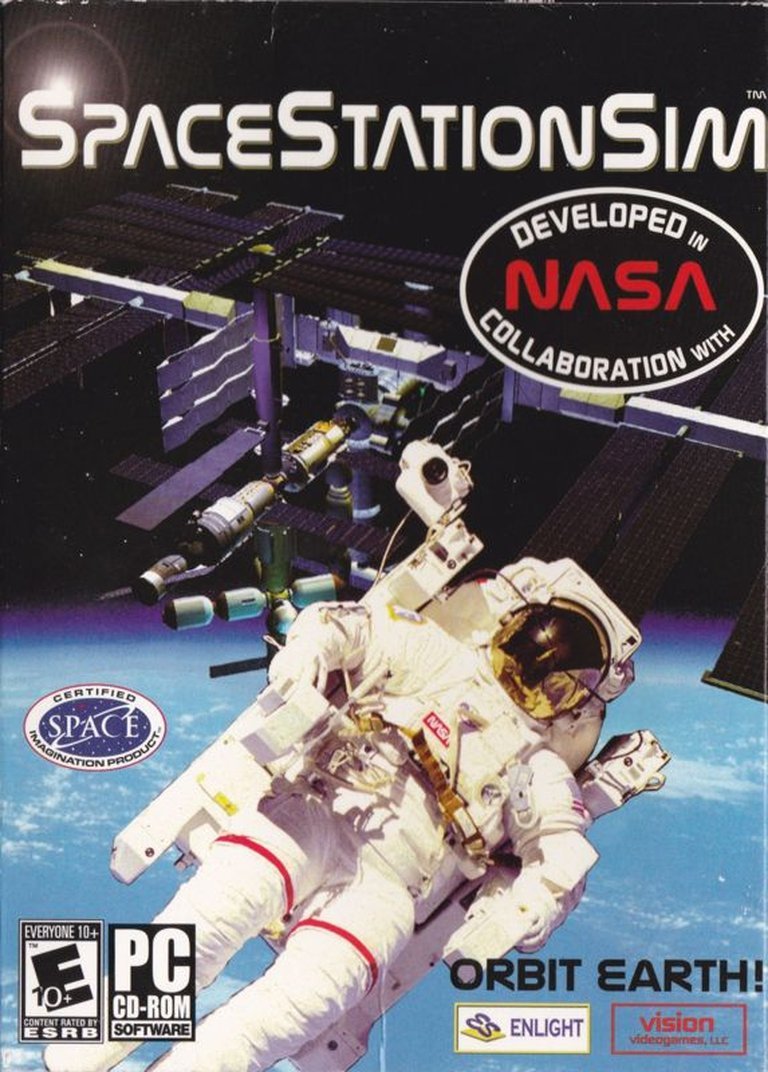

- Publisher: 1C Company, Vision Videogames, LLC

- Developer: Vision Videogames, LLC

- Genre: Simulation

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Base building, Crew management, Real-time, Resource Management, Task Queue

- Setting: Earth Orbit, Space station

- Average Score: 52/100

Description

SpaceStationSim is a simulation game set aboard the International Space Station where players take on the role of Mission Control, directing astronauts in tasks like research, repairs, exercise, and daily activities while managing station resources, crew health, and customization of modules and astronaut skills to maintain smooth operations.

Gameplay Videos

SpaceStationSim Free Download

SpaceStationSim Cracks & Fixes

SpaceStationSim Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (57/100): Although Space Station Sim offers up a unique experience and is the only game that gives you the opportunity to actually manage a space station and the astronauts who inhabit it, it doesn’t offer the sort of excitement and intensity you’d expect.

thespacereview.com : SpaceStationSim eschews the hard-core management focus and deserves merit as the first simulation of space station life, bladder-challenged astronauts and all. It is an immersive and endearing game that, although ultimately a bit shallow, those with a love of games and space should consider picking up.

mobygames.com (55/100): As boring as real space work

ign.com (45/100): This one needs to go back to Space Camp.

SpaceStationSim: A Well-Intentioned Missile That Never Reached Orbit

In the mid-2000s, the life simulation genre was dominated by the cultural behemoth The Sims. Its open-ended, “play god” formula seemed infinitely applicable. So when Vision Videogames announced SpaceStationSim—a game that transplanted that core loop onto the meticulously documented, real-world environment of the International Space Station (ISS) with NASA’s direct cooperation—it promised something unique: the mundane, the scientific, and the profoundly challenging made playable. What emerged, however, was a fascinating case study in the perils of prioritizing authenticity over engagement, a game that serves more as a digital museum exhibit than a compelling interactive experience. As a historical artifact, it is invaluable; as a game meant to entertain, it remains stubbornly, profoundly earthbound.

1. Introduction: The Allure and Agony of Hyper-Reality

SpaceStationSim represents a holy grail for a specific subset of gamers and educators: a truly authentic simulation of modern human spaceflight, divorced from the fantasy of aliens, laser guns, and interstellar travel. Its central promise was to let players manage every aspect of life aboard the ISS, from the grand—launching new modules, coordinating multinational crews—to the intimate: scheduling meal times, ensuring exercise regimes are followed, and monitoring psychological health. The thesis of this review is that SpaceStationSim is a game of profound contradictions. It is a technically impressive, deeply researched love letter to the ISS program that fundamentally misunderstands why people play games. Its greatest strength—unprecedented realism and educational value—is also the root of its fatal flaw: the conversion of awe-inspiring human achievement into a repetitive, often tedious, series of chores. It is less a “game about space” and more a “game about bureaucratizing space,” and for most players, that distinction is everything.

2. Development History & Context: A Costly Leap of Faith

The journey of SpaceStationSim is as notable as the game itself, embodying the ambition and risk of niche game development in the mid-2000s.

The Studio and the Vision: The game was developed by Vision Videogames, LLC, a small independent studio based in Towson, Maryland. Its origins trace back to GRS Games, which began development in 2003 before being acquired by Vision Videogames in a management buyout in March 2004. The driving force was President and Producer Bill Mueller, a man who clearly harbored a deep passion for space exploration. His stated belief—”One real day at NASA is more exciting than an imaginary day anywhere else”—sets the philosophical tone for the entire project. This was to be a simulation of real work, not a power fantasy.

The NASA Partnership: The project’s defining feature was its Space Act Agreement with NASA. This was not mere licensing; it was a deep collaboration. Over 60 NASA civil servants, program managers, and astronauts provided input, reviewed designs, and even served as beta testers. NASA also contributed via its partners: the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), the Russian Space Agency (RSA), the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), and the European Space Agency (ESA). The goal was unbounded authenticity, from the technical specifications of modules to the psychological dynamics of crew rotations. This level of institutional buy-in was (and remains) exceptionally rare for a commercial game.

Technological and Financial Constraints: The development spanned five years with a core team of about 20, swelling with NASA contributors. The budget started at $3 million and rose to $3.5 million—a modest sum even for the time, especially for an ambitious 3D simulation. The game was built using the RenderWare engine, a popular but aging middleware solution by 2005, which likely contributed to its dated visuals, particularly the much-criticized launch cutscenes. The technological constraints are evident in the limited draw distance, simple character models, and repetitive animations of flitting astronauts. The scope was monumental: simulating a complex, modular space station in real-time with independent AI agents, each with needs and skills. The coding challenge for a small team was immense.

The Gaming Landscape: SpaceStationSim arrived in October 2005 (Windows) amidst a crowded simulation market. The Sims 2 (2004) had just refined its genre formula. More critically, the space simulation genre was bifurcated: on one side, hard-core management sims like the Space Empires series; on the other, action-oriented space operas like Freelancer or the upcoming EVE Online (2003). There was no popular middle ground for a slow, thoughtful, systems-heavy sim about living in space rather than conquering it. The game was announced for a PlayStation 2 version but it was never released, highlighting the technical hurdles and uncertain market.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Story of Bureaucracy and Biology

SpaceStationSim has no traditional narrative, no scripted story beats, no antagonists. Its “plot” is the one the player writes: the saga of their particular space station. This places enormous weight on its thematic underpinnings and AI-driven drama.

Thematic Premise: The core theme is the triumph of human cooperation and scientific curiosity in an inhospitable environment. It is a game about sustaining life, not taking it. The player acts as the “Chief Administrator of NASA” (or, in some descriptions, “Mission Control”), a god-like figure responsible for the physical and psychological well-being of the crew and the integrity of the station. This immediately frames the experience as one of stewardship, not conquest.

The Astronauts as Agents of Theme: The crew are not characters with backstories but bundles of attributes: skills (biomedicine, astrotechnology, etc.), personality traits (playful, workaholic), and needs (hunger, bladder, social, fun). The game’s drama emerges from the friction between these systems. An astronaut with a “poor work ethic” might neglect a critical repair, leading to an oxygen leak. A specialist too focused on science might ignore exercise, leading to muscle atrophy. The infamous “space tourists” (in Hawaiian shirts) are a literal comic relief element, disrupting workflows and creating chaos. The theme here is that even in the most high-tech environment, human nature—laziness, boredom, the need for leisure—is the eternal variable. The game argues that the real challenge of long-duration spaceflight is not technology, but sociology and psychology.

The Absence of Grand Narrative: This is where the game’s philosophy clashes with player expectation. There is no external threat, no Cold War-style race, no mystery to solve. The drama is entirely internal and systemic. A meteor strike is a random event; a decompression is a failure of maintenance. This hyper-realism strips away the cinematic, heroic narrative of space exploration popularized by Hollywood. The theme becomes “space is a job,” and for many, that is an insufficient motivator. The lack of aClear, overarching goal—beyond “build a big station and don’t let everyone die”—is repeatedly cited as a major flaw. Without a “top of your job” or “huge mansion” equivalent from The Sims, the player has no ladder to climb, no ultimate trophy to strive for. The game’s world is a beautifully simulated, but static, bucket.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Sims, But With Oxygen Tanks

Mechanically, SpaceStationSim is a direct descendant of The Sims, transplanted into a 3D ISS environment. The player’s interface is a combination of a top-down “Mission Control” map and a 3D view of the station interior. The core loop is a cycle of Plan → Launch → Manage → React.

Core Systems:

1. Station Building: The player constructs the ISS from dozens of realistic modules and components provided by NASA and its international partners. These include laboratories, airlocks, living quarters, and truss segments. Placement is constrained by real-world connection rules (e.g., a module must connect to a specific node). This is a major source of satisfaction for the enthusiast, offering a deep, puzzle-like construction experience.

2. Crew Management: Using an “Astronaut Builder,” players create or recruit crew members, assigning them to specialty roles. The primary interaction is the task queue. Clicking on an object (a treadmill, a microscope, a food packet) brings up a menu of possible interactions. The player queues these tasks to fulfill the crew’s needs (eat, sleep, exercise, hygiene, fun, social) and mission objectives (conduct experiment X, repair component Y).

3. Resource & System Management: Beyond individual needs, the player must monitor global station systems: oxygen levels, CO2 scrubbers, power consumption, water supply, and international goodwill (the game’s currency). Launching resupply missions (via Russian Soyuz or Progress spacecraft) costs goodwill and requires careful scheduling.

4. Crisis Simulation: The game throws random events: meteoroid punctures (causing depressurization), equipment failures, and fires. These require immediate, prioritized response, often from specific skilled crew members. The tension here is genuine, though the feedback on why a crisis occurred or how to prevent it next time is often opaque.

Innovations and Flaws:

* Innovation: Its most significant innovation is the systemic integration of biological and psychological needs with a complex, modular engineering environment. It correctly identifies that the “job” of an astronaut is a balancing act between science, maintenance, and self-care. The AI, as noted in the player review, is adequate: needs-driven and capable of autonomous action once trained, freeing the player to focus on macro-management later.

* Fundamental Flaws:

* The “Sims” Problem, Amplified: Without the career tracks, clear aspirations, and rich object interactions of The Sims, the core loop feels hollow. There is no sense of progression for the player, only the gradual expansion of the station.

* Opaque Systems: The user interface, while functional once mastered, offers poor feedback. Why did a repair fail? Why is an astronaut ignoring a critical task? The manuals and in-game descriptions for components are often poorly written, as the critic from gameZine (UK) noted. This creates a punishing trial-and-error learning curve that alienates all but the most dedicated.

* Pacing and Tedium: Watching simulated astronauts float through a corridor to eat a meal is slow. The game’s real-time pacing means 20 minutes of play might cover only a few hours of in-game time. This isn’t inherently bad—it’s a sim—but there’s little “juice” or visual reward to make the waiting engaging. As the player review bluntly states, it’s “as boring as real space work.”

* Lack of Failure Clarity: When things go wrong, the “why” is often mysterious. Did the CO2 scrubber fail because it needed maintenance, because a crew member didn’t fix it, or because the design was flawed? The game doesn’t guide the player toward understanding systemic root causes, leading to frustration.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: A Clinical, Authentic Void

The presentation of SpaceStationSim is a direct reflection of its priorities: accuracy over artistry.

Visual Direction & Atmosphere: The game uses a muted, realistic color palette—grays, whites, electric blues—faithfully recreating the interior of the ISS. The 3D models of modules and equipment are based on real NASA diagrams, offering a veritable tour of the station’s anatomy. This is its greatest atmospheric strength: a sense of place. You are inside the International Space Station. However, this fidelity comes at a cost. The graphics are dated, with low-poly models, simple textures, and stiff animations. The much-maligned launch sequences are indeed “terrible… made 10 years ago,” featuring pre-rendered or overly simplistic cutscenes that fail to evoke the awe of a rocket launch. The human models are particularly lacking, contributing to the feeling of managing automatons rather than people.

Sound Design: The soundscape is sparse and functional. The low hum of machinery, the ping of alerts, the occasional radio chatter—all are suitably sterile and technical. The background music is a small, repetitive loop that quickly becomes grating, as the player review notes. There is no soaring orchestral score to inspire. The only “cinematic” audio is the introductory movie, which features an “introductory movie… pretty nice, though even that song’s rather boring.” This aural minimalism reinforces the game’s clinical, workmanlike tone. It sounds like a space station, not a game, which is both its intention and its drawback.

Contribution to Experience: The art and sound successfully create an atmosphere of isolation, technical precision, and quiet tension. They make the player feel the claustrophobia and procedural gravity of the environment. Yet, they also amplify the lack of excitement. The world is visually and aurally monotonous, mirroring the perceived monotony of the gameplay itself. It is an immersive simulation, but an emotionally flat one.

6. Reception & Legacy: A Niche Curiosity

SpaceStationSim was not a commercial success. Its reception is a study in polarization, largely split between space enthusiasts and general gamers.

Critical Reception: The game holds a Metacritic score of 57% based on 5 reviews. The range is telling:

* Positive (e.g., Out of Eight – 75%, The Space Review): These reviews celebrate its uniqueness and educational value. “One of the best contemporary space program-themed computer games for kids,” and “an immersive and endearing game.” They acknowledge the steep learning curve but reward the player’s patience with a sense of genuine accomplishment in building a functional orbital complex.

* Negative (e.g., IGN – 45%, gameZine (UK) – 40%): These reviews are scathing. IGN calls it “too simple and lacking the stats for space nerds,” and “probably better for kids,” while also citing a “steep learning curve.” gameZine states it’s “far too complicated and unforgiving for laymen” and has “next to no assistance to break you in gently.” The consensus among detractors is that the game is caught between two worlds: too shallow for hardcore simmers wanting deep engineering stats, and too complex and dull for casual players.

* The Player Verdict: The voice of the general public is best captured by the MobyGames user review: “In a word, dull.” Its damning conclusion—”This is a game about modern space work… take something that’s already boring… and make it even more boring”—resonates with the silent majority who abandoned the game after a couple of days.

Commercial and Cultural Legacy: The game sold poorly. It is remembered today primarily through two lenses:

1. The NASA Connection: It remains a notable example of a government agency directly collaborating on a commercial game for public outreach and, intriguingly, for internal use. As the NASA Spinoff article details, Vision Videogames later used the engine to build “SimCEV” for NASA to simulate the Crew Exploration Vehicle, proving the simulation’s utility as a professional visualization tool.

2. A Cautionary Tale: It serves as a classic case study in the “simulation vs. fun” debate. It demonstrated that raw authenticity and systemic depth are not sufficient substitutes for compelling gameplay loops, clear feedback, and player-driven goals. It’s the antithesis of the arcadey, action-packed space fantasies that dominate the market. For every person who dreamt of managing their own ISS, ten more dreamt of piloting a starfighter.

Its influence on subsequent games is minimal. It has no direct descendants. Its influence is more conceptual, a reminder of a path not taken. The idea of a hyper-realistic, mundane space sim would later see more sophisticated attempts (like Stationeers or even aspects of Kerbal Space Program‘s career mode), but SpaceStationSim remains the first serious, officially-sanctioned stab at the concept.

7. Conclusion: A Flawed Artifact of a Noble Ambition

SpaceStationSim is not a “good game” by any conventional metric. It is boring, opaque, and fails to provide the psychological hooks—clear progression, exciting failures, emergent storytelling—that make games compelling. Its interface is clunky, its pacing glacial, and its aesthetic drab. For the vast majority of players, the recommendation from the Moby review is correct: stick to The Sims or any number of more exciting space games.

However, as a historical artifact, it is fascinating and important. It is a testament to a specific, profound optimism about spaceflight—that its very mundanity is worth celebrating and simulating. It is a digital monument to the thousands of flight controllers, engineers, and astronauts whose daily work is the invisible backbone of humanity’s presence in orbit. Vision Videogames, with NASA’s blessing, built a working model of that world. They succeeded brilliantly in their primary goal: creating an accurate, comprehensive simulation of the ISS. They failed, perhaps inevitably, in translating that accuracy into a broadly enjoyable interactive experience.

Its place in video game history is secure, not as a classic, but as a sobering case study. It proves that simulation fidelity is a tool, not a goal. It highlights the chasm between educational/software utility and entertainment value. Most of all, it reminds us that the magic of space for most people lies not in the exquisite tedium of maintenance, but in the boundless frontier of the unknown—a frontier this game, by its very nature, could not explore. SpaceStationSim is a well-built monument to the reality of space, and that is precisely why it remains, for most, a fascinating but empty place to visit.