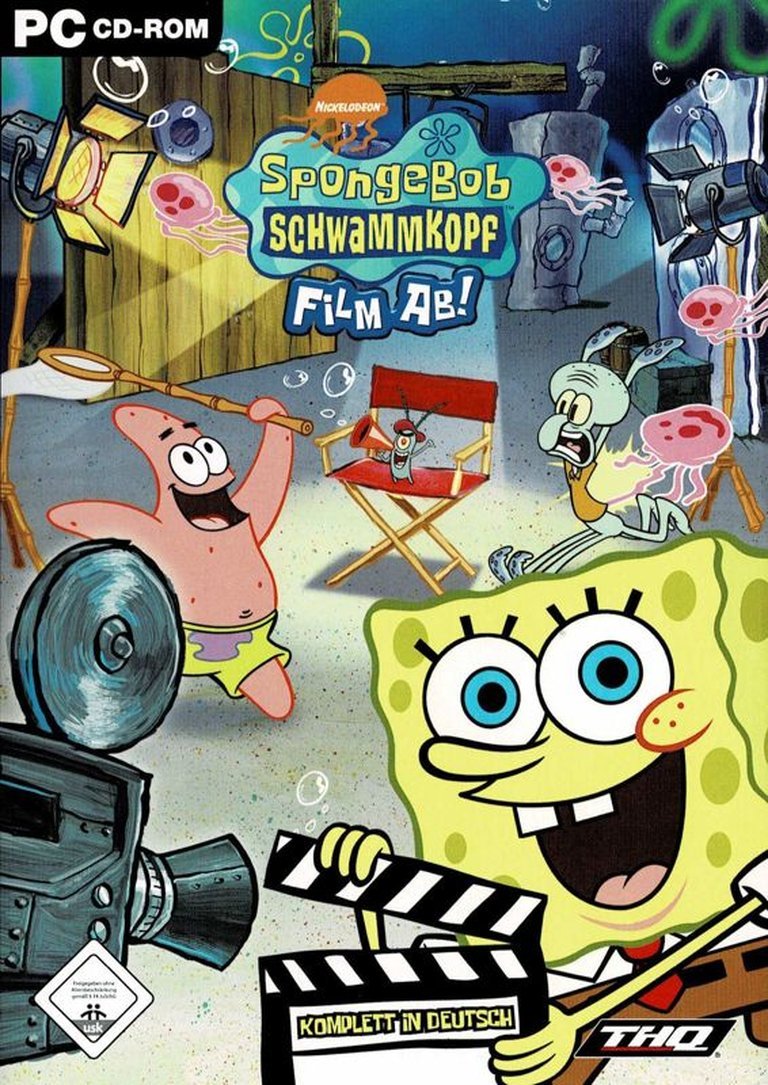

- Release Year: 2005

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Noviy Disk, THQ Inc.

- Developer: AWE Productions, Inc.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Mini-games, Puzzle

- Setting: Aquatic, Underwater

- Average Score: 59/100

Description

In ‘SpongeBob SquarePants: Lights, Camera, Pants!’, players take on the role of SpongeBob as he navigates the underwater city of Bikini Bottom to save the TV series ‘The New Adventures of Mermaidman and Barnacle Boy’ when its cast goes missing. This Windows-exclusive single-player adventure involves exploring locations, conversing with iconic characters to recruit them, and solving puzzles through mini-games to progress the story.

Gameplay Videos

SpongeBob SquarePants: Lights, Camera, Pants! Free Download

SpongeBob SquarePants: Lights, Camera, Pants! Mods

SpongeBob SquarePants: Lights, Camera, Pants! Guides & Walkthroughs

SpongeBob SquarePants: Lights, Camera, Pants! Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (59/100): Hardly deep, but an entertaining set of party games for your younger brother or sister that you may just get a kick from too.

SpongeBob SquarePants: Lights, Camera, Pants! Cheats & Codes

PC

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| 486739 | Unlock Silver Story mode challenges |

| 893634 | Unlock Hook, Line, And Cheddar mini-game |

| 977548 | Unlock all action figures |

GameCube

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| 486739 | Unlock Silver story mode challenges |

| 893634 | Unlock Hook, Line, And Cheddar mini-game |

| 977548 | Unlock all action figures |

GameBoy Advance

Input codes using a CodeBreaker or Gameshark device.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| 35082794 B972 | Mastercode |

| 83003BF0 03E7 | 999 Lives |

| 8300050C 03E7 | 999 Stars |

| 8300042C FFFF | All Games Unlocked |

| 83000EB0 0303 | Unlimited Health |

| 83000EB2 0303 | Unlimited Health |

SpongeBob SquarePants: Lights, Camera, Pants!: A Fragmented Legacy of Bikini Bottom’s Theatrical ambitions

Introduction: The Casting Call Heard ‘Round the World (Well, Bikini Bottom)

In the mid-2000s, the SpongeBob SquarePants video game lineage was a curious study in contrasts. Following the acclaimed 3D platformer Battle for Bikini Bottom (2003) and the movie tie-in, the franchise stood at a crossroads. The next title, Lights, Camera, Pants!, would not be a singular vision but a tripartite experiment, a single IP fractured across three distinct gameplay genres on multiple platforms. Released in October 2005 for PlayStation 2, Xbox, GameCube, Windows PC, and Game Boy Advance (with DS and PSP versions cancelled), it represents a fascinating—and ultimately flawed—moment when Nickelodeon and THQ attempted to serve every conceivable audience with one conceptual umbrella. Its thesis is deceptively simple: Bikini Bottom is producing a special anniversary episode of the in-universe show The New Adventures of Mermaid Man and Barnacle Boy, and the town’s inhabitants compete for roles. Yet, this core premise unravels into three disparate experiences, each with its own development lineage, mechanical identity, and critical fate. This review will argue that Lights, Camera, Pants! is less a cohesive game and more a snapshot of mid-2000s licensed game development’s fragmentation—a well-intentioned but diluted effort where the sum of its parts struggles to form a satisfying whole, saved only by the sheer force of its source material’s charm and a handful of surprisingly clever minigame concepts.

Development History & Context: Three Studios, One License, Divergent Visions

The game’s development history is a map of early-2000s licensed game strategy. THQ, holding the lucrative Nickelodeon license, deployed different studios to tackle different platforms, a common practice to maximize market coverage but one that often sacrificed a unified design vision.

- Console Versions (PS2, Xbox, GameCube): Developed by THQ Studio Australia (credited as “Studio Oz” in some materials), these versions were conceived as a multiplayer party game, explicitly modeled after the Mario Party formula. Utilizing the RenderWare engine, the team (directed by Jon Cartwright and Dave MacMinn, designed by Craig Duturbure) focused on creating a suite of 30 minigames (“auditions”) structured around a board-game-like story mode. The vision was clear: a pick-up-and-play, competitive experience for groups of friends, leveraging the franchise’s humor in short bursts.

- Windows PC Version: Handled by AWE Productions, the studio behind previous PC SpongeBob titles like Employee of the Month. Tasked with a market that expected different play patterns, AWE pivoted to a point-and-click adventure game. As described on MobyGames, the player, as SpongeBob, must “walk around and talk to the various inhabitants in order to convince them” to join the production, with minigames acting as obstacles or puzzles to solve. This was a pragmatic adaptation for a platform where local multiplayer was less common, but it created a fundamental dissonance in tone and structure from its console siblings.

- Game Boy Advance Version: Developed by the revered WayForward Technologies, the GBA entry became a side-scrolling platformer with character-switching mechanics reminiscent of Super Mario Bros. 2. Designed by Marc Gomez, it structured its levels around four distinct worlds (Mermalair, S.S. Rest Home, etc.), blending platforming, driving, and minigames. Notably, it excluded Plankton from the playable roster and altered the plot to focus on finding the missing Mermaid Man and Barnacle Boy, rather than competing for a villain role.

This platform-based fragmentation meant the game had no singular “canonical” experience. The technological constraints were significant: the RenderWare-based console versions had to manage split-screen or shared-screen multiplayer, leading to simpler graphics and occasional frame-rate dips. The GBA’s hardware limitations dictated its 2D sprite-based aesthetic and level size. The PC version, while potentially more detailed, suffered from a different constraint: the need to translate fast-paced party action into a slower, narrative-driven detective format. The gaming landscape of 2005 was dominated by the rising popularity of party games (Mario Party 6/7, WarioWare), but also saw a decline in purely kids-focused licensed games’ critical prestige. Lights, Camera, Pants! arrived as a product trying to be everything to every SpongeBob fan on every platform, a strategy that rarely yields a masterpiece.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Meta-Humor and the Illusion of Production

The game’s narrative scaffolding is where its metatextual cleverness shines brightest, even when the gameplay varies. The central conceit—that the player is participating in the production of an episode of The New Adventures of Mermaid Man and Barnacle Boy—is a brilliant piece of licensed game storytelling. It allows the game to be about the process of making a SpongeBob episode, a concept ripe with potential for satire and fan service.

Console/PC Core Plot: Producer Gil Hammerstein (voiced by Nolan North, a notable piece of “other Darin” casting) is frantic because the cast of the anniversary special has failed to show. In the console version, this sets up a competitive audition; in the PC version, it leads to SpongeBob becoming a de facto casting agent. Thematically, this frames the entire endeavor as a chaotic, behind-the-scenes farce, perfectly mirroring the show’s own absurdist tone. The ultimate goal is to win the role of the Sneaky Hermit, the episode’s supervillain.

The Produced Episode: “The New Adventures of Mermaid Man and Barnacle Boy”: This is the game’s masterstroke. After completing the console version’s Story Mode (Bronze, Silver, or Gold difficulty), the player unlocks a full 30-minute animated “episode” constructed from the won audition scenes. The plot, as detailed on Wikipedia and TV Tropes, is a classic Mermaid Man pastiche: the heroes are arrested for stealing the Sand Stadium, team up with arch-nemeses Man Ray and the Dirty Bubble after the Hermit steals their lairs, and defeat the Hermit by using pepper to trigger a catastrophic sneeze. The execution is rife with the show’s signature tropes:

* Enemy Mine: The core driver of the plot.

* Mermaid Man’s Senility: His mishearing of “tall building in its sights” as “tights,” “permit test bites,” etc., is pure G-rated absurdity.

* Cross-Cast Role & Gender Flip: The Hermit’s gender matches the actor’s (female for SpongeBob/Patrick/Sandy, male for Squidward/Krabs/Plankton), a clever nod to theatrical tradition.

* Reality Is Unrealistic: The “Anachronic Order” of filming (by location, not story) is accurately portrayed, with Gil explaining this is how movies are really made.

The PC version offers a more interactive, shorter version of this, allowing prop and casting choices, directly tying the player’s adventure to the final product. This creates a powerful feedback loop: your actions in the game directly shape a canonical-ish piece of SpongeBob content. The GBA version, by separating the search for the missing heroes from the final “episode” minigame romp, loses this potent meta-layer.

The underlying theme is one of creative desperation and collaborative absurdity. Everyone in Bikini Bottom desperately wants to be in the show, mirroring the actors’ desperation in the meta-episode. The game celebrates the chaotic, communal effort required to produce entertainment, a reflection of the real-world, collaborative chaos behind SpongeBob itself. The dialogue, while criticized by IGN as repetitive, is packed with character-appropriate quips and fourth-wall breaks that sell the premise.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Trilogy of Disparate Designs

The gameplay is the game’s most defining—and divisive—feature. There is no single “Lights, Camera, Pants!” gameplay; there are three.

1. Console Versions (PS2, Xbox, GameCube): The Party Game Framework

This is the version most associated with the title’s legacy. Its structure is a hybrid of a board game and a minigame compilation.

* Story Mode Progression: Players (1-4, with AI fillers) choose a character and compete across 8 themed “locations” (Krusty Krab, Goo Lagoon, Boating School, etc.). Each location contains 3 “audition” minigames. To advance, a player must achieve a “popularity points” quota that varies by Story Mode phase (Bronze/Silver/Gold) and, crucially, also have the highest score among all players for that location. If no one meets the quota, the lowest-scoring minigame is replayed. This quota system is poorly communicated, a major source of “Guide Dang It!” frustration noted on TV Tropes. Tie-breakers use Rock-Paper-Scissors (a show reference) or other special minigames.

* Minigame Design (30 total, 24 in story): This is where the game lives or dies. The quality is inconsistent. Highlights include:

* Flippin’ Out (Krusty Krab): A fast-paced Krabby Patty assembly line with risk/reward for flipping green (Plankton’s) patties.

* Floor It! (Boating School): A driving test where SpongeBob’s competence is player-dependent, showcasing “Adaptational Intelligence.”

* Rock Bottom (Sand Stadium): A rhythm game where each character plays their iconic instrument (SpongeBob’s guitar from the movie, Patrick’s drums from “Band Geeks,” Squidward’s clarinet), a deep “Continuity Nod.”

* Breakout (Jail): A tense escape with spotlights, capturing the “Great Escape” trope.

* Loot Scootin’ (Flying Dutchman’s Graveyard): A risk-laden coin-collecting game with a notoriously obscure gold bar objective for full completion.

Lowlights include overly simple, repetitive, or frustrating games like Rubble Rabble (button-mashing) or Two-Up (pure luck). The “Aggressive Play Incentive” in Hook, Line, and Cheddar (wedgie mechanics) is a standout design choice that encourages chaos.

* Character & Progression: All 6 characters (SpongeBob, Patrick, Squidward, Sandy, Mr. Krabs, Plankton) are functionally identical, differentiated only by color and voice lines. Progression is gated by Story Mode phases. Collectibles (action figures, artwork) are Permanently Missable Content if not earned before moving to the next phase, a severe and criticized design flaw. “Artificial Stupidity” is easily exploited on the “Silly” AI setting.

* Verdict: A competent but shallow party game framework. The minigame variety is good, but depth and replayability are low compared to Mario Party. The core loop is marred by opaque objectives and punishing collectible locks.

2. Windows PC Version: The Point-and-Click Adventure Pivot

Developed by AWE Games, this is a fundamentally different game.

* Gameplay Loop: A traditional 2D point-and-click adventure. Players explore a simplified Bikini Bottom map, click on characters and objects to solve puzzles, collect props, and convince citizens to audition. Minigames appear as discrete puzzles to overcome (e.g., a driving test, a rhythm challenge).

* Plot Integration: The narrative is more personal and quest-driven. SpongeBob is directly responsible for “saving” the show by recruiting the cast. It incorporates specific episode references as side quests (“Mermaid Man and Barnacle Boy III” and “I’m Your Biggest Fanatic”), unlocking Man Ray and Kevin the Sea Cucumber as potential actors, a nice “Pragmatic Adaptation” touch.

* Strengths & Weaknesses: It better captures the exploratory, conversational spirit of the show’s early seasons. However, it loses the frantic multiplayer energy. The puzzles are generally simple, aligning with its “Everyone” ESRB rating. The final movie is shorter and more customizable, but the overall experience is less dynamic and arguably less “gamey” than the console version. It’s a respectful adaptation for its platform but feels like a different beast entirely.

3. Game Boy Advance Version: The Platformer Detour

WayForward’s expertise in crafting tight 2D platformers is evident.

* Gameplay Loop: A level-based platformer across four worlds. Players can switch between SpongeBob, Patrick, Sandy, and Squidward (Plankton and Mr. Krabs absent) at any time, each with slight ability differences (e.g., Sandy can glide, Patrick has high strength). Levels mix platforming, vehicle sections (boat driving), and scripted minigames.

* Plot: A modified quest to find the missing Mermaid Man and Barnacle Boy, with acting roles as rewards for finishing levels.

* Design: Collectible Golden Stars act as currency for lives and unlockable minigames. The structure is more linear and goal-oriented than the console version’s free-form competition. It successfully translates the SpongeBob world into a competent, if not exceptional, GBA platformer. Its main critique is that it feels more like a generic licensed platformer with SpongeBob skins than a unique expression of the IP’s party-game core concept.

Synthesis: The three versions demonstrate a lack of coherent design vision. The console game’s party mechanics are the most conceptually aligned with the “audition” premise but suffer from execution flaws. The PC game’s adventure approach makes narrative sense but is less engaging as a game. The GBA game is a solid platformer that barely connects to the core “audition” theme. A player’s experience is entirely determined by their platform of choice, a fragmentation that diluted the game’s potential cultural impact.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Capturing the Aesthetic, If Not the Soul

Visual Direction: The game’s visuals are a faithful, if simplistic, translation of the show’s aesthetic.

* Console/PC: Characters are brightly colored, low-polygon 3D models with exaggerated animations that often capture the show’s rubber-hose looseness. Environments like the Krusty Krab and Chum Bucket are recognizable but blocky, a product of RenderWare’s limitations and the need for readable gameplay spaces in minigames. The PC version’s 2D art is cleaner and more illustrative, better evoking the show’s layout style.

* GBA: The sprite work is excellent for the hardware, with large, expressive character sprites and well-drawn backgrounds. It arguably best captures the show’s 2D charm.

* Presentation: The interface is slick and themed, with Gil Hammerstein’s bombastic hosting providing constant, if repetitive, audio commentary. The cinematic cutscenes—especially the full 30-minute episode—are the visual highlight. They use the in-game engine but with enhanced camera work and lighting, successfully mimicking the show’s episode structure and delivering genuine laughs through visual gags and Deadpan Snarker dialogue from Squidward-centric roles.

Sound Design: This is a major strength across all versions.

* Voice Acting: The entire core cast (Tom Kenny, Bill Fagerbakke, Rodger Bumpass, Carolyn Lawrence, Clancy Brown) returns, delivering lines with impeccable timing. Nolan North’s Gil Hammerstein is a boisterous, perfect foil. The sheer volume of context-specific voice clips for wins, losses, and minigame actions is impressive and sells the comedy.

* Music: Composers Charlie Brissette/Hamilton Altstatt (consoles), Joe Abbati (PC), and Martin Schioeler (GBA) created a soundtrack that is widely praised by fans as one of the best in any SpongeBob game. It deftly mixes tense party-game themes with direct homages to the show’s iconic library (the “Rock Bottom” guitar solo, the Krusty Krab theme). The music energizes minigames and underscores cutscenes with authentic SpongeBob musical comedy.

* Sound Effects: Crisp, familiar, and humorous. The clack of a Krabby Patty flip, the boing of a jellyfish, Squidward’s weary sigh—all are present and correct.

The audiovisual presentation is arguably the game’s most successful element. It feels like SpongeBob, even when the gameplay does not.

Reception & Legacy: A Divided Cult Classic

Lights, Camera, Pants!’ reception was harshly divided by platform, a rarity that underscores its fragmented identity.

Critical Reception:

* Console Versions (PS2, Xbox, GameCube): Received mixed-to-negative reviews. Metacritic scores hovered in the high 50s (PS2: 59, Xbox: 57). Critics praised the presentation, voice acting, and number of minigames but universally panned the lack of depth, repetitive dialogue, simplistic AI, and the infuriatingly opaque quota system. Eurogamer’s 4/10 Called it “hard to see how even the most ardent SpongeBob fan could get a lot out of this,” citing a small minigame pool and too many “niggles.” IGN’s 7/10 was the high point, calling it a “surprisingly well-made party game” but noting it “lacks depth.” The comparison to Mario Party was inevitable and unflattering; it was seen as a shallow imitation without that series’ addictive board-game metagame.

* PC Version: Fared significantly better, with a Metascore of 68/100. MobyGames’ critic average was 47% based on 3 European magazines, but this is misleading. The 7Wolf Magazine review (64%) explicitly praised the “pleasant impressions for fans,” suggesting the adventure format better suit the PC audience’s expectations for a SpongeBob game. The point-and-click format was seen as more thoughtful and less repetitive than the console version’s grind.

* GBA Version: Has no Metacritic score but is generally considered a solid, above-average platformer for the system by retro standards, praised for WayForward’s typical polish and character-switching mechanic.

Commercial & Cultural Legacy:

Commercially, it was likely a modest success, riding the wave of SpongeBob mania, but it left no significant mark on sales charts. Its legacy is that of a curiosity and a cautionary tale.

1. The Last of Its Kind: It was the final SpongeBob game for the original Xbox and one of the last major multi-platform releases before the franchise shifted to more focused, often 3D platformer or story-driven adventures (Creature from the Krusty Krab, Underpants Slam).

2. A Forgotten Experiment: The divergent platform approaches are rarely discussed in modern SpongeBob game retrospectives. The console version is often cited as an example of a missed opportunity in the party genre, while the PC version is a footnote in AWE’s catalog. The GBA version is remembered fondly by WayForward fans.

3. Nostalgic Reappraisal: In the 2020s, user scores on Metacritic (7.5 for PS2) and eBay reviews show a significant nostalgia gap. Players recalling it from childhood emphasize its hilarious cutscenes, fun minigames (“I remember playing this at Blockbuster!”), and great soundtrack, dismissing critical complaints as overblown. This is common for licensed games of the era—their technical flaws are forgiven for the sheer joy of interacting with a beloved world.

4. Influence: It had no direct influence on the industry. The party game genre evolved along Mario Party and Jackbox lines. The SpongeBob franchise itself moved toward more cohesive 3D platformers (Battle for Bikini Bottom Rehydrated) and later, rhythm and open-world games. Its primary influence is as a historical artifact: a snapshot of a publisher hedging its bets across formats with a single, loosely connected concept.

Conclusion: A Flawed but Fascinating Artifact of Its Era

SpongeBob SquarePants: Lights, Camera, Pants! is not a great game by any conventional metric. Its console version is a structurally flawed party game with decent minigames hampered by poor progression design. Its PC version is a pleasant but lightweight adventure that feels separate from its namesake. Its GBA version is a competent platformer that barely fits the core premise. Taken together, they represent a development strategy of brute-force market coverage over creative cohesion.

Yet, to dismiss it entirely is to ignore its undeniable strengths and unique position. It contains some of the best voice acting and musical adaptation in any SpongeBob game. The meta-narrative of producing a Mermaid Man episode is a brilliantly conceptualized piece of fan service that results in a genuinely funny, self-contained cartoon. For fans willing to engage with its quirks, the console version’s minigames—flipping patties, jamming on guitar, jailbreaking—provide bursts of authentic Bikini Bottom chaos. The PC version offers a quieter, more exploratory corner of that world.

Its place in video game history is not as a pioneer or a classic, but as a case study in the pitfalls of platform-based fragmentation. It proves that a strong license and faithful aesthetics cannot overcome fundamental design incoherence and a failure to communicate core mechanics to the player. It is the gaming equivalent of a well-intentioned, slightly messy school play where the sets are perfect, the actors are hilarious, but the script and stage directions are a mess. You leave entertained by the performances and the world, but acutely aware of the missed potential. For historians, it is a vital data point in the evolution of licensed games and the brief, awkward adolescence of the party game genre on home consoles. For fans, it remains a beloved, chaotic, and deeply flawed time capsule—a game where the joy is found not in the victory, but in the silly,熟悉的 (familiar) anarchy of being in Bikini Bottom, even if you’re not quite sure what you’re supposed to be doing.

Final Verdict: 6.5/10 – A deeply flawed, platform-dependent curiosity saved by its source material’s irresistible charm, top-tier voice work, and a stellar soundtrack. Its legacy is one of “what could have been” had its three versions shared a single, polished vision.