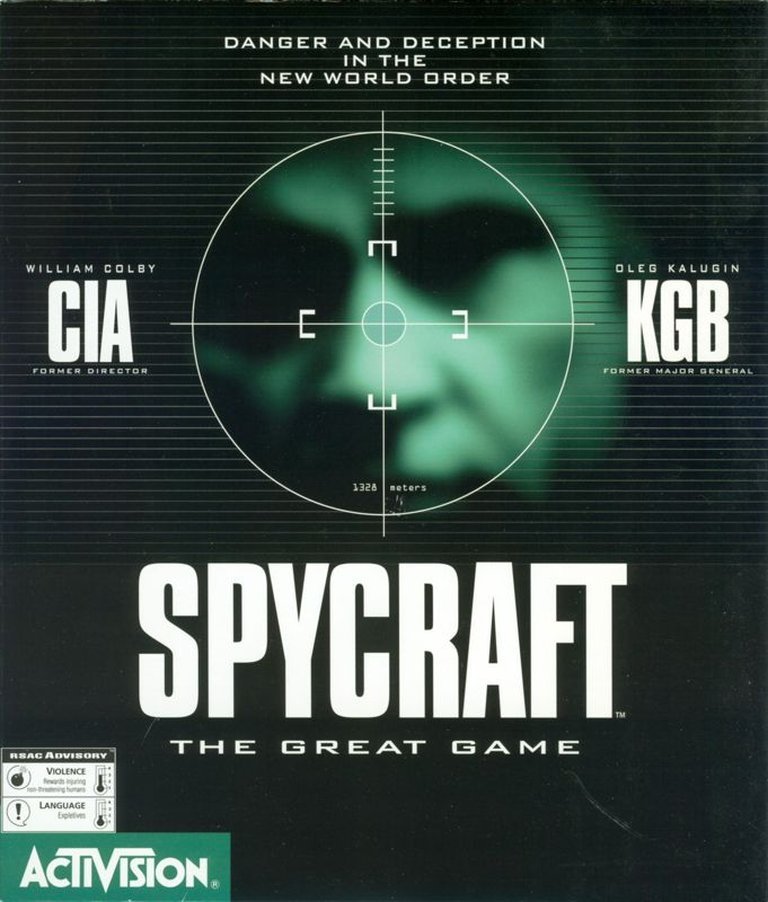

- Release Year: 1996

- Platforms: DOS, Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Activision, Inc.

- Developer: Activision, Inc.

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Graphic adventure, Puzzle elements, Simulated Internet, Simulation, Torture

- Setting: D.C., Washington

- Average Score: 80/100

Description

Spycraft: The Great Game is an adventure game set in Washington D.C., where you assume the role of a newly recruited CIA operative investigating the assassination of a Russian presidential candidate. Drawing on authenticity from former heads of the CIA and KGB, the game immerses you in a spy thriller filled with puzzle-solving, information analysis via a PDA-like InteLink, and moral choices that unravel a conspiracy reaching the highest echelons of US and Russian governments.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Spycraft: The Great Game

Spycraft: The Great Game Free Download

Spycraft: The Great Game Guides & Walkthroughs

Spycraft: The Great Game Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (80/100): This is not a game whose video segments are mere story-props that leave the player behind, but one designed to keep the player actively involved.

ign.com : The stakes couldn’t possibly get any higher.

Spycraft: The Great Game: Review

1. Introduction: The Authenticity Gamble

In the mid-1990s, the video game industry was in the throes of an “FMV (Full Motion Video) revolution,” a brief, feverish period where studios believed the future of interactive entertainment lay in blending cinematic storytelling with player agency. Amidst a sea of campy detective stories and fantasy adventures, Activision’s Spycraft: The Great Game (1996) stood apart with a singular, audacious proposition: what if a game about espionage was crafted with the direct input of the men who once ran the world’s most notorious intelligence agencies? By securing the consultation—and on-screen appearances—of former CIA Director William Colby and former KGB Major General Oleg Kalugin, Spycraft didn’t just aspire to realism; it claimed a lineage from the actual “great game” of Cold War intelligence. This review argues that Spycraft is a profound paradox: a landmark of narrative ambition and systemic authenticity that was simultaneously crippled by the technological constraints and commercial volatility of its era. It is a game that understood the grammar of spycraft—the tedious document analysis, the moral compromises, the bureaucratic paranoia—but was often lost in translation due to the clunky interfaces and hardware demands of 1996. Its legacy is not one of mainstream success or a direct lineage to modern games, but as a fascinating, flawed time capsule of a unique moment when video games, geopolitics, and the dying breath of the FMV format collided.

2. Development History & Context: The Hollywood Gambit

The Studio and the Vision: Spycraft was developed by Activision at a pivotal, turbulent time for the company. After a period of financial difficulty and a 1991 bankruptcy, Activision was under new leadership (including a young Bobby Kotick) and desperately seeking a knockout hit to re-establish its prominence. The mid-90s FMV boom, sparked by titles like Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective and The 7th Guest, represented the industry’s belief that CD-ROM technology could deliver “interactive movies” with adult themes and high production values. Activision’s vision for Spycraft was explicitly to create a “serious” spy thriller for adults, moving beyond the cartoonish James Bond fantasy toward the “dirty tricks and covert actions” of a Tom Clancy novel or John le Carré tale.

The Unlikely Consultants: The core of this vision was the unprecedented collaboration with William Colby and Oleg Kalugin. Their involvement, as detailed in the Polygon documentary The Great Game: The Making of Spycraft and the Substack analysis by Elizabeth P. Dove, was not born from a deep, shared creative partnership but from a confluence of post-Career circumstances. Both men had been effectively ousted from their respective agencies—Colby for his perceived over-cooperation with the Church Committee investigating CIA abuses, and Kalugin for his internal criticisms of KGB corruption and his subsequent conviction for treason in absentia by Russia. By the mid-90s, living in the United States and publishing memoirs (Colby’s “Honorable Men” and Kalugin’s “The First Directorate”), they were experts for hire, navigating the post-Cold War media landscape. Activision sought their “authenticity” as a marketing stamp; the consultants, in turn, likely saw participation as a form of cultural relevance and a platform to shape the popular narrative of their former professions. Their on-screen appearances as themselves, offering briefings to the player, were less about substantive design input and more a powerful symbolic gesture, blurring the line between game and historical artifact.

Technological Constraints & The FMV Era: The game was developed on a budget exceeding $3 million—a substantial sum for the time. Production was treated like a film shoot. Director Ken Berris (as recounted in the Polygon documentary) built elaborate, physical sets, including a painstaking replica of the CIA’s headquarters in Washington, D.C., eschewing the green-screen compositing common in other FMV games. This commitment to cinematic quality came at a severe cost: the game spanned three CD-ROMs, and its video demanded hardware (a 486/66 MHz CPU, 16MB RAM, a fast CD-ROM drive, and a supported sound card) that was at the very high end of consumer PCs in 1996. As multiple reviews (from GameSpot, Jeanne on Moby) attest, installation and playback issues with Sound Blaster drivers and system requirements were a major barrier to entry, turning even a high-end Pentium 166 into a source of frustration. Furthermore, the game’s innovative “WebLink” feature—which required logging into Activision’s servers to access dynamically updated news and dossiers—was a groundbreaking idea for 1996 but rendered completely inert once the servers were shut down, a decision the user review from Katakis rightly criticizes as shortsighted.

The Gaming Landscape: Spycraft arrived at a crucial inflection point. The puzzle-driven adventure and FMV genres were peaking. Myst-like graphic adventures were giving way to the first wave of 3D accelerated graphics (the N64 and PlayStation launched in 1996). While critically darling, FMV games were increasingly seen as a technological dead-end by gamers eager for polygonal worlds and real-time action. Spycraft, with its focus on desk-bound analysis and linear FMV sequences, was poised between two eras: too complex and hardware-hungry to mass-market, yet conceptually too mature and “un-game-like” for the burgeoning action market.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Morality of Intelligence

Plot Structure and Setting: The narrative, written by James Adams (a noted non-fiction espionage author), is a taut post-Cold War thriller. The player is “Thorn,” a newly minted CIA Case Officer. The assassination of a liberal Russian presidential candidate in Red Square swiftly unravels into a global conspiracy involving a mercenary syndicate called PROCAT, a CIA mole codenamed “Harmonica,” and the theft of a nuclear pit destined for a Punjabi arms dealer, Onyx. The plot sends Thorn from a training farm (“The Farm”) in the U.S. to Moscow, London, Heidelberg, Tunisia, and finally Crimea, constructing a classic spy puzzle box where every clue connects to a larger pattern.

Themes of Glasnost and Disillusionment: The game’s central theme, brilliantly contextualized by Maya Vinokour in the Polygon documentary, is the anxious optimism and underlying fear of the early post-Soviet era. The story hinges on a Russian election—a moment of fragile hope for democracy—and the persistent threat that hardliners would sabotage it to restore the old order or provoke a nuclear confrontation. This reflects a real American anxiety: had the Cold War truly ended, or was it merely mutating? The villain, Procat, is not a nation-state but a corrupt ideology, a network of former intelligence operatives from both sides (ex-CIA, ex-KGB, ex-MI6) who profit from instability. This mirrors the real-world concern about “loose nukes” and the privatization of intelligence expertise after the USSR’s collapse.

Moral Ambiguity and Player Agency: Where Spycraft transcends its FMV peers is in its systemic embrace of moral compromise. The game does not frame choices as “good vs. evil” but as “effective vs. ineffective.” Two key mechanics illustrate this:

1. The Torture Option: During installation, players can enable a “realistic” torture sequence involving escalating electrocution of a suspect. As the player review notes, this mechanic brutally simulates the CIA’s historical use of such techniques.Success yields information; failure kills the subject and triggers a “You are sent to prison” game over. This isn’t a sensationalized mini-game; it’s a damning simulation of a bureaucratic, procedural evil.

2. The Final Choice: The climax presents a quintessential spy’s dilemma. Having located the Russian mole (your own boss, DDO Warhurst) and the traitorous campaign manager, you witness the Russian SVR agent Yuri Gromchevsky prepare to arrest the candidate—an act that would destabilize Russia and doom the disarmament treaty. Your choice is to shoot Yuri (ensuring stability, earning a medal, but morally sanctioning murder) or refuse (maintaining personal integrity but triggering chaos and martial law). There is no “perfect” ending; each victory is pyrrhic, a direct reflection of the “intelligence work has one moral law: it is justified by results” philosophy noted in the Substack article.

Characters as Archetypes and Prophets: The live-action cast, composed of skilled character actors (James Karen as the treasonous Warhurst, Dennis Lipscomb as the weary DCI Sterling, the ever-reliable Charles Napier), delivers a grounded, weary authenticity. Most compelling are Colby and Kalugin themselves. They appear not as cartoon villains or heroes, but as weary, pragmatic elders. Their cameos are brief, but their presence is a constant thematic undertone—they are the real architects of the world the player navigates, men who have seen the consequences of the very games being played. As the Polygon documentary’s expert, Maya Vinokour, notes, they function as “props” or “husks,” their authority borrowed to lend credibility to a fictional simulation. This self-awareness is the game’s deepest, most unsettling layer.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Desk Jockey’s Odyssey

The Core Loop: Analyst, Not Action Hero: Spycraft’s genius lies in its rejection of the James Bond fantasy. The core gameplay loop is investigative, procedural, and deeply cerebral. You are not scaling buildings or engaging in shootouts; you are a desk officer managing a case. The primary interface is the InteLink PDA, a simulated computer system that serves as your browser, email client, database, and toolbox.

* Email: The game’s narrative progresses via emails from your team and contacts. Sending an inquiry often yields an immediate, context-aware reply, creating a believable flow of information. This was a novel use of simulated online communication.

* Tools: You regularly employ specialized analysis tools:

* Photographic Analysis: Doctoring a photo by placing objects at precise angles to elicit a reaction from a suspect (Jeanne’s review highlights its “ridiculously difficult” specificity).

* Sound Analysis: Isolating background noises (train whistles, aircraft) from a recording to triangulate a location.

* Cypher Tool: Decoding intercepted communications.

* Kennedy Assassination Tool: A chillingly named program used to plot the trajectory of the assassin’s bullet in Red Square, a direct nod to the real-world techniques of the Warren Commission.

Puzzle Design: Logical but Demanding: The puzzles are widely praised for their logical coherence and realism. They require careful data collation, cross-referencing (flight manifests, financial records, news archives), and deductive reasoning. As Computer Gaming World noted, they set “a new standard for plot depth and realism.” However, they are also criticized for a lack of scaling difficulty and occasional “idiot-proofing” that undermines player agency. The Power Play review felt patronized by excessive in-game guidance.

Branching Paths and Consequence: The narrative is largely linear, but key decision points create meaningful branches. The “bad path” of rifling your supervisor’s office for blackmail material, the torture choice, and the final shoot/don’t shoot decision all lead to different outcomes. Replaying the game reveals altered sequences and dialogue, a feature noted by Chris Martin, though the overall plot structure remains fixed.

Flawed Systems: The most notorious flaw is the saving mechanism. Saving requires navigating back to a specific terminal in your office, a tedious process that breaks tension. More fundamentally, the game’s ambition outstripped the technology. The WebLink component, designed to enhance realism with live news, was a dependency on external servers that do not exist today, severing a key part of the intended experience.

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: The Weight of the Real

The Aesthetic of Bureaucracy: Spycraft’s world is not one of glamour but of beige, fluorescent-lit offices, cramped apartments, and rain-slicked European streets. The art direction, led by Gary Brunetti and team, prioritizes mundane realism. Your “office” is a cluttered desk with a CRT monitor, a phone, and a stack of dossiers. The FMV sequences are shot on practical sets that feel authentic—the CIA briefing room, a Moscow safehouse, a London pub. This aesthetic reinforces the game’s thesis: spying is 99% paperwork.

Performance and Presence: The use of real, working-class actors (rather than stars) is a masterstroke. It grounds the melodrama in a recognizable reality. Dennis Lipscomb’s DCI Sterling radiates exhausted authority; James Karen’s Warhurst embodies smarmy, ambitious betrayal. Their performances, as noted in player reviews, make the FMV segments watchable without the urge to skip. The cameos by Colby and Kalugin are fascinating直视 直视 (zhíshì – to look straight at) historical figures. Their slightly stiff, formal delivery feels authentic to their roles as bureaucrats, not actors.

Sound as a Gameplay Tool: Sound design is not ambient but integral. Voiceprint matching is a critical gameplay mechanic. The score is appropriately tense and minimalist, often giving way to diegetic sounds—the crackle of a radio, the dial tone of a phone—that the player must actively listen to for clues. This sonic focus treats the player as an intelligence officer, not a tourist.

The Shanghai II Anomaly: The inclusion of Shanghai II: Dragon’s Eye as a fully playable game within your inventory (accessed via a floppy disk on your in-game terminal) is a brilliant meta-commentary. It provides a deliberate, mechanical break from the high-stakes narrative, a moment of pure, abstract puzzle-solving that ironically highlights the contrast between Spycraft’s intense realism and the pure abstraction of classic gaming. It acknowledges the player’s need to play in the traditional sense, even within a “realistic” simulation.

6. Reception & Legacy: Critical Acclaim, Commercial Silence

Launch Reception: Critics in 1996 were mostly dazzled, awarding an average score of 78%. Highlights included perfect scores from Generation 4 (France) and Entertainment Weekly, which praised its “brainy Beltway analysis” and “frighteningly authentic” scenario. PC Zone declared it “unsuckable,” and Computer Gaming World gave it 4.5/5, calling it a “groundbreaking adventure” that “sets a new standard for plot depth and realism.” The Macworld “Best Multimedia Game” award and Computer Gaming World‘s “Readers’ Choice: Adventure Game of the Year” cemented its critical standing.

However, cracks were evident. GameSpot (7.1/10) and German magazines like PC Action (77%) and PC Games (65%) found the gameplay too passive and sedate compared to action-oriented spy games. The most common critique, from Power Play and Just Games Retro, was its linearity and lack of replay value—a “mystery” with a fixed solution, more akin to a novel than a traditional game. The technical hurdles were a universal bugbear, with Jeanne describing the constant reinstalls needed just to get the sound drivers to work.

Commercial Failure and the Lost Sequel: Despite shipping 140,000 units by June 1996 (a solid figure for a niche adventure), the game failed to recoup its multi-million dollar budget. As the user review from Katakis starkly notes, “sales of this game have been disappointing.” The promised Spycraft II vanished. The death of William Colby in a mysterious canoe accident in April 1996—just two months after release—looms large over this history. While no direct causal link is proven, it severed a key link to the game’s claimed authenticity and any momentum for a sequel. The planned Sega Saturn port and DVD-ROM version were cancelled.

Evolution of Reputation: Over time, Spycraft has become a cult classic and a subject of historical fascination rather than a remembered blockbuster. The 2024 Polygon documentary and the 2023 Digital Antiquarian blog post by Jimmy Maher have been pivotal in rehabilitating its reputation, framing it not as a failed game but as a crucial, symptomatic artifact of its time. In 2011, Adventure Gamers ranked it #90 on its “Top 100 All-Time Adventure Games” list, acknowledging its enduring design merits. Today, its availability on Steam and GOG.com (with an emulated DOSBox version) allows new audiences to experience it, warts and all. Its legacy is subtle:

* Precursor to Investigative Games: Its focus on database analysis, evidence correlation, and non-combat problem-solving foreshadows the detective mechanics of later games like Condemned or The Painscreek Killings.

* The “Authenticity” Benchmark: It set a high bar for narrative research and consultant involvement, a model later seen (with varying success) in military shooters (America’s Army) and historical games.

* Cautionary Tale on Online Integration: Its broken WebLink is a museum piece of early, fragile online integration, a lesson in the perils of depending on external servers for core gameplay.

* A Snapshot of a Moment: It perfectly encapsulates the 1995-1996 zeitgeist: post-Cold War anxiety, FMV hype, and a sincere, if clumsy, attempt to treat video games as a medium for serious political fiction.

7. Conclusion: The Case Officer’s Report

Spycraft: The Great Game is not a flawless masterpiece. Its technical demands, linear structure, and dependence on a defunct online service are significant, often frustrating, barriers. The gameplay, for all its clever puzzles, can feel like elaborate paperwork. Yet, to dismiss it as merely another FMV curio is to miss its profound ambition. It is one of the few games to directly engage with the ethics of intelligence work, forcing players to confront torture, betrayal, and the cold calculus of geopolitical stability. Its production was an audacious fusion of Hollywood craft and Silicon Valley techno-optimism, anchored by the chillingly real presence of men who had literally played the game for real.

In the history of video games, Spycraft occupies a unique niche. It is neither a classic that defined a genre nor a forgotten footnote. It is a what-if, a fascinating prototype of a more serious, adult-oriented interactive narrative that the industry ultimately moved away from in favor of 3D action and open-world exploration. Its reputation has evolved from “critically acclaimed commercial disappointment” to “culturally significant artifact.” It succeeds not as a perfect game, but as a meticulously constructed simulation of a mindset—the paranoid, analytical, morally gray world of the spook. For the patient player willing to wrestle with its interface, it remains a deeply immersive and thought-provoking experience, a digital time capsule from a moment when the Cold War had just ended, the internet was nascent, and video games were daring to ask: what does it really mean to be a spy?

Final Verdict: A brilliant, broken, essential historical artifact. 7.5/10 – A landmark of thematic ambition and systemic realism, held back by the technological limitations and commercial pitfalls of its FMV era. It is less a game to be “won” and more a world to be inhabited and interrogated.