- Release Year: 1995

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: John Councill IV

- Developer: John Councill IV

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade

- Setting: Animals: Insects

- Average Score: 66/100

Description

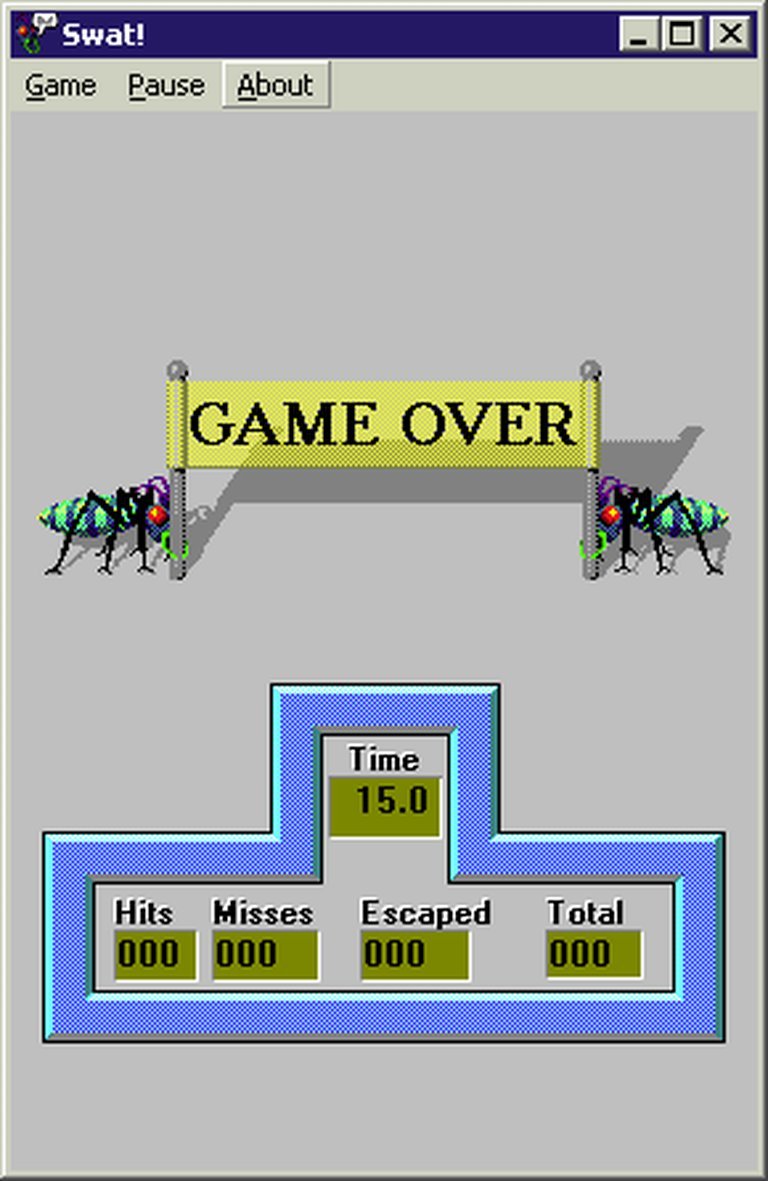

Swat! is a simple yet engaging freeware game where players use a mouse-controlled hammer to swat flies that appear on the screen. The objective is to earn points by squashing flies, while losing points for misses or letting them escape. Players can adjust the game speed, fly appearance rate, and duration for a customizable experience.

Gameplay Videos

Swat! Serial Keys

Swat! Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (62/100): Police Quest: SWAT immerses players into the high-stakes world of law enforcement, focusing on the tactical operations of the SWAT team.

gamespot.com (37/100): SWAT begins with an interesting premise, but the designers seem to have paid too much attention to detail in the wrong areas.

imdb.com (100/100): This is one of my best Christmas gift I got when I was a child in the 90s, when I watch YouTube and I’m sad to see it’s not that appreciated as it should be.

Police Quest: SWAT: A Defining Moment in Tactical Simulation

Introduction

In the mid-1990s, as CD-ROM technology unlocked new frontiers for interactive storytelling, Sierra On-Line embarked on an ambitious experiment: merging the procedural authenticity of their signature Police Quest series with the immersive promise of full-motion video (FMV). The result, Police Quest: SWAT (1995), stands as a landmark in tactical simulation history—both a flawed relic of its era and a surprisingly prescient blueprint for modern squad-based shooters. This review examines the game through the lens of its development, narrative innovation, mechanical depth, and enduring legacy. While its FMV presentation and strict adherence to police procedure may feel antiquated today, Police Quest: SWAT remains a fascinating artifact that redefined how games could simulate high-stakes law enforcement operations, cementing the SWAT subseries as a cornerstone of tactical gaming.

Development History & Context

Police Quest: SWAT emerged from Sierra On-Line’s creative crucible under the direction of Tammy Dargan, who served as writer, designer, and producer. The project leveraged Sierra Creative Interpreter 2 (SCI2), the same engine powering Phantasmagoria and Gabriel Knight 2, but repurposed it for simulation rather than pure adventure. This technological choice enabled the game’s signature blend of scanned photograph backgrounds and green-screened FMV actors—a resource-intensive approach that necessitated four CD-ROMs for storage, a testament to the era’s capacity constraints. The development team included real LAPD SWAT advisors Bob Bennyworth and Steve Massa, ensuring procedural authenticity in tactics, equipment, and radio protocols.

Released on September 30, 1995 amid the FMV craze, the game capitalized on the CD-ROM revolution’s promise of cinematic immersion. However, it also represented a strategic pivot for Sierra. While the Police Quest series had always emphasized realism, this title marked a decisive shift toward simulation over traditional point-and-click adventure. This reflected broader industry trends: the rise of genre-blending titles like MechWarrior 2 and the increasing demand for “edutainment” experiences. Yet Sierra’s ambition outpaced contemporary hardware limitations, resulting in a game that pushed boundaries while occasionally stumbling under their weight.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The narrative unfolds through the eyes of “SWAT Pup,” an anonymous rookie navigating the LAPD Metropolitan Division’s D Platoon. This framing device intentionally distances the player from a defined personality, emphasizing role immersion over character development. The plot is divided into two distinct acts: exhaustive training sequences and three operational missions. The training phase, set at the Los Angeles Police Academy in Elysian Park, dominates the gameplay. It consists of lectures, marksmanship drills, and tactical briefings delivered by live-action instructors—transforming the game into an interactive documentary on SWAT procedures.

The three missions—each with randomized outcomes—showcase the game’s thematic core: the moral weight of law enforcement. In the first, players negotiate with Lucy Long, a delusional elderly woman barricaded in her North Hollywood home. Success hinges on de-escalation, not force. The second mission involves a warehouse standoff with an armed burglar who may have taken hostage Hector Martinez, forcing players to balance risk against protocol. The finale targets terrorists at Eastman Enterprises, a government contractor tied to the military-industrial complex, culminating in a bomb-defusal scenario. Each mission’s branching narratives underscore the game’s preoccupation with consequence: one wrong order can lead to reprimands, injury, or death.

This structure creates a powerful thematic duality: the game celebrates SWAT’s heroism while exposing its psychological toll. The emphasis on arrest over lethal force, and negotiation over aggression, reflects mid-90s debates about policing, making the narrative unexpectedly relevant. Though hampered by FMV’s inherent limitations, the story’s procedural rigor remains compelling, offering a rare glimpse into the ethics of tactical operations.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Police Quest: SWAT eschews real-time action in favor of a point-and-click interface married to radio command systems. Players interact with environments by clicking objects and issuing LASH radio commands using verb-noun pairs (e.g., “SHOOT SUSPECT,” “COVER DOOR”). This creates a unique gameplay loop where tactical decisions matter more than reflexes. The training phase, while tedious for modern players, was innovative for its depth: marksmanship drills required accounting for windage and distance, while entry tactics emphasized breaching angles and room-clearing procedures.

The missions themselves are tense, unpredictable affairs. Randomized elements—such as a suspect’s location or hostage status—encouraged replayability. Players could assume roles chosen during training: as an element leader, issuing commands to teammates, or as a sniper, accounting for wind effects during shots. This role-based differentiation added strategic depth, though the limited mission count (just three) felt sparse. Critically, the game penalized deviations from protocol—shooting without provocation or failing to follow orders resulted in reprimands or game overs. This created a uniquely punishing yet educational experience.

UI design was functional but dated. The inventory system managed gear, while the radio interface enabled precise team coordination. Adjustable settings—like fly spawn rate and game speed—allowed customization but couldn’t compensate for the lack of save functionality. Ultimately, the gameplay succeeded in simulation but faltered as entertainment, demanding patience over excitement.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The game’s world-building is its most enduring achievement. Los Angeles is rendered with photorealistic meticulousness: the LAPD Academy’s sterile corridors, the sun-bleached facades of North Hollywood homes, and the industrial gloom of the warehouse setting all scanned from real locations. This authenticity extended to equipment details—M4 carbines and breaching tools accurately replicated from SWAT armories.

Artistically, Police Quest: SWAT exemplified Sierra’s FMV aesthetic. Live-action performances overlaid on static backgrounds created a “dollhouse” effect, with actors’ sprites interacting with environments. While the acting occasionally veered into camp (notably in the training segments), the SWAT team’s professionalism shone through, grounding the fantasy in reality. Sound design was equally refined: Dan Kehler’s ambient score underscored tension, while digitized radio chatter and weapon reports created immersive audio layers. The LASH radio, in particular, became a narrative device, relaying mission updates with clipped urgency.

This audiovisual synergy fostered a palpable atmosphere of professional urgency. The game never sensationalized violence; instead, it mirrored the procedural sterility of police work, making moments of genuine threat—like the warehouse standoff—feel unnervingly authentic.

Reception & Legacy

Police Quest: SWAT polarized critics upon release. Next Generation awarded it two stars, praising its educational content but lambasting its “lack of control,” while PC Zone celebrated its “gun-toting cop fun” with a 83/100 score. Mixed reviews masked robust sales: the game moved over 1 million units by 2000, becoming Sierra’s surprise hit. Its commercial success stemmed from a perfect storm of timing: the Police Quest brand’s built-in audience and the public’s fascination with post-Rodney King LAPD culture.

The game’s legacy is twofold. It spawned the SWAT subseries, evolving from FMV origins to the tactical masterpiece SWAT 3: Close Quarters Battle (1999). More broadly, it influenced the tactical shooter genre, predating Rainbow Six (1998) by years in its emphasis on procedure over action. Modern re-releases on GOG.com and Steam have introduced it to new audiences, though its reputation remains niche. Some view it as a flawed but fascinating artifact of FMV’s brief dominance; others critique its dated mechanics. Yet its core DNA endures: the idea that games can simulate the moral complexity of law enforcement without sacrificing tension.

Conclusion

Police Quest: SWAT is a time capsule of ambition and compromise. As a product of its era, it reflects the mid-90s obsession with FMV and procedural simulation, warts and all. Its rigid gameplay and dated presentation may alienate modern players, but its commitment to authenticity remains commendable. The game succeeded not as an action title, but as an interactive documentary—a rare achievement that made players feel the weight of a badge.

While its critical reception was mixed, its commercial and historical impact is undeniable. It birthed a genre and proved that tactical simulations could be both educational and thrilling. For all its flaws, Police Quest: SWAT stands as a vital chapter in video game history—a testament to Sierra’s willingness to innovate, and a reminder that the most enduring games are often those that dare to simulate worlds as complex as our own. In the crowded landscape of tactical shooters, this flawed pioneer still deserves respect: not for what it was, but for what it dared to become.