- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Macintosh, Pippin, Windows

- Publisher: Bandai Digital Entertainment Co., Ltd., Bandai Digital Entertainment Corp.

- Developer: 7th Level, Inc.

- Genre: Simulation

- Perspective: Fixed / flip-screen

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Life, Mini-games, Social simulation

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

- Average Score: 67/100

Description

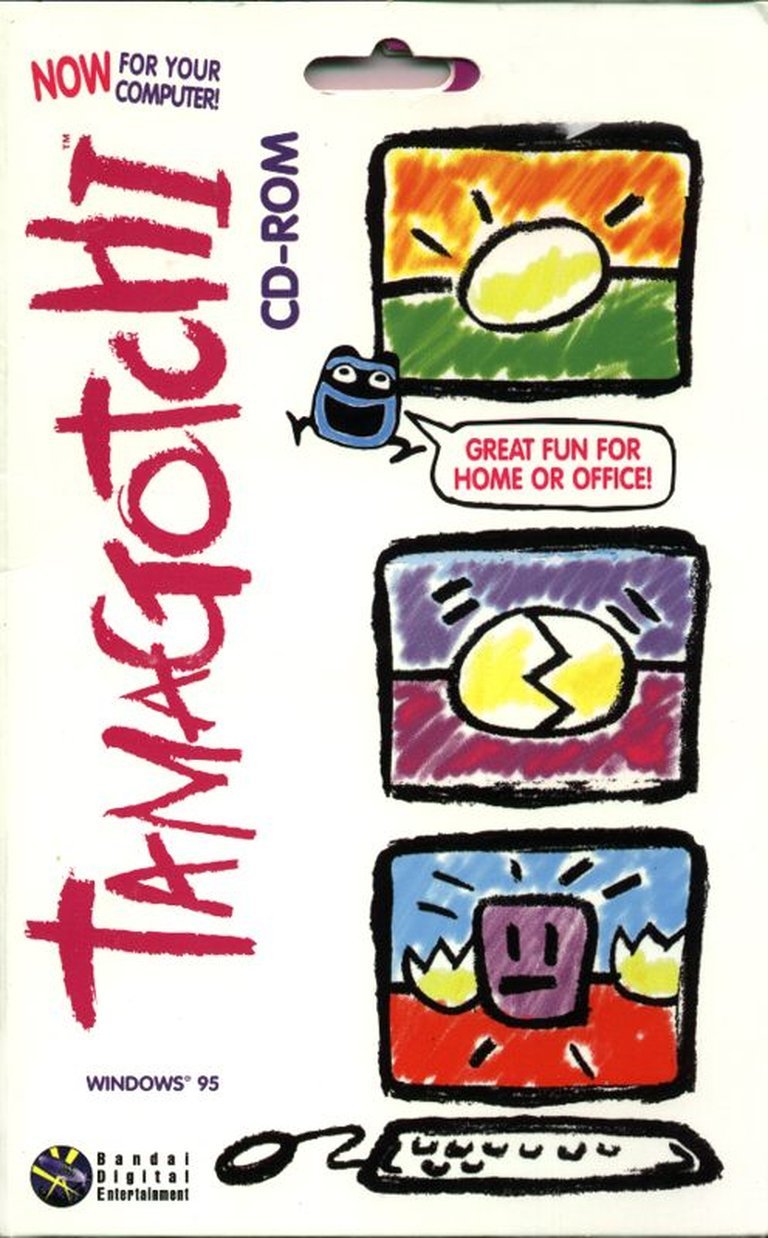

Tamagotchi CD-ROM is a life simulation game released in 1997 that brings the popular virtual pet toy to PC, Macintosh, and Pippin platforms. Players adopt and care for a digital Tamagotchi, tending to its needs from hatching as an egg through adolescence and into adulthood, requiring regular feeding, cleaning, and play to keep it happy and healthy. Developed by 7th Level, Inc. and published by Bandai Digital Entertainment, the CD-ROM version expands upon the original handheld experience with enhanced graphics, additional mini-games, a scrapbook feature, animated screensaver, and a day care center for when players are away. Set in a sci-fi, toy-inspired world, the game faithfully retains the core logic of the physical Tamagotchi while offering more visual appeal and PC interactivity, making it a niche but nostalgic desktop pet experience.

Gameplay Videos

Tamagotchi CD-ROM Free Download

Cracks & Fixes

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (50/100): If you really must have a virtual pet, but don’t want to be seen in public with one, buy this game.

Tamagotchi CD-ROM: Review

Introduction

When the classic handheld Tamagotchi burst onto global markets in 1996, its neon‑colored eggs and frantic heartbeat viewers’ thumbs felt like a new personal‑tech craze. The device’s true power, however, lay not in its hardware but in the emotional loop it created: a digital tiny life that demanded attachment, routine, and, through its resurrection, a shared sense of guardianship among children worldwide. In 1997 Bandai responded with Tamagotchi CD‑ROM—a Windows‑based, Lip‑Sync potential function repurposing the handheld’s core mechanics for PCs, Macs, and even Apple Pippin. My thesis: while Tamagotchi CD‑ROM is an earnest and surprisingly sophisticated adaptation of the original’s emotional engine, its design choices—especially the minimalist gameplay and problematic longevity—demonstrate a cautious, short‑sighted attempt to translate a tactile handheld experience into a home‑computer context.

Development History & Context

7th Level and Bandai Digital Entertainment Collaboration

Bandai Digital Entertainment Corp. partnered with 7th Level, Inc. to deliver a PC version. The resulting team of 74, as documented on MobyGames, included key figures such as executive producer Sharon Hustwit, chief software producer Martin Takahashi, and director Dan Kuenster, an experienced visual auteur who sourced the animated character designs later used in Tamagotchi Video Adventures.

Technological Constraints of 1997

At the time of release, Windows 95 dominated the PC market, and CPU benchmarks were still handled by Intel Pentium processors with 8‑10 MHz graphics cards. The team adopted a fixed / flip‑screen visual style to minimize processor demands, mimicking the handheld’s two‑dimensional sprite logic. The software also supported mouse input exclusively, excluding a keyboard‑based interface that might have allowed deeper interaction.

Market Landscape

The late ’90s were an era of transition: the emergence of personal digital assistants and mobile phones, while handheld consoles like the Game Boy enjoyed massive popularity. Virtually every developer was attempting to piggyback on Bandai’s thriving IPs. However, Tamagotchi CD‑ROM did not simply copy fields; it provided a new ecosystem: care center, order‑in‑time scrupulous reminders, and a scrapbook – a memory module unavailable on the handheld. In essence, the game aimed to encourage routine, day‑to‑day PC engagement rather than short, portable play sessions.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The Opening Story Sequence

The game begins with an opening cut‑scene featuring Maskutchi and Zuccitchi heading “to planet Earth” aboard a UFO. Their bark at the egg’s wetness, argument over clean‑up, and eventual crash landing on a tropical island establish the narrative tone—humorous anthropomorphised childhood fables that mirror real‑world pet‑ownership. The voice‑work by the ensemble includes Cam Clarke and Sig Jen, smoothing an otherwise “furry” aesthetic.

Hatching to Evolution: The Life Schema

The core plot is a linear logistic function that mirrors the original Tamagotchi’s life stages:

– Baby (≈90 min)

– Child (≈2–3 days)

– Teen (≈2 days)

– Adult (≈10–20 days in‑earth)

Each phase is accompanied by shifting dialogues, a subtle choreography, and a distinct visual identity. When babies hatch, the game randomly selects either Babytchi or ShiroBabytchi, guaranteeing visual and behavioral variability. The story’s intelligence also reflects the pet evolution mechanic: as the pet becomes ill or if it experiences an overwhelming happiness spike, an automatic evolution occurs by swapping the sprite—no animation aside from a “twinkly cadence” cue.

Themes and Moral Lessons

The underlying theme is one of responsibility and interdependence. The recurring attention icon humblifies the player: neglect is not just a visual cue but a moral warning. The care center, the day‑to‑day discipline system, and the alarm to wake the pet early reinforce that guardianship is a continuous practice, not a one‑time event. The inclusion of a scrapbook, which stores letters sent by the Tamagotchi when leaving Earth, subtly conveys closure and remembrance, a concept rarely found in children’s games.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Core Loop: Life Management

- Feeding: Click the food icon or select the pre‑set menu; the pet’s hunger meter (represented as bread) replenishes.

- Bathing & Hygiene: The cleanliness meter must be periodically balanced; lack of cleanliness triggers snake‑like behavior (eyes shifting).

- Medication: A simple “give medicine” option; failing to administer medicine when the pet displays symptoms leads to a higher probability of early death.

Mini‑Games

- Left‑Right Game – a nod to the original’s directional guessing; mandatory: win at least 3 of 5 rounds to raise happiness.

- Shell Game – hide-and‑seek with three shells; required 2 victories out of 6 to keep the pet smiling.

- Gotchi Ball Game – break-glass–like “Breakout” adaptation; three lives count as a reward for the pet; loses reduce weight.

The minigames provide the rare extended gameplay beyond the repetitive life cycle. However, the scoring system is primitive (win/loss only) and offers little incentive for re‑play.

Care Center & Alarm System

- Care Center: A 72‑hour day‑care that automatically feeds, cleans, and dispenses medicine. While ongoing, the pet trim stays similar; but discipline calls reduce 25% of ‘Assistance’ after 24 hours, automatically dropping care quality.

- Alarm: A clever mechanic that allows the player to wake the pet for early wake‑ups. This will alter its bedtime, but only if the pet is not in the care center.

Both systems showcase a time management strategy hidden behind a simple UI. The alarm’s limitations and the care center’s penalty for over‑use hint at an early attempt to model responsibility as a realistic system.

Interface & UI

The game’s UI is heavily menu‑structured, where each action is a button on a fixed background. The interface features animated thumbs for the icon, captivating Heart-shaped hearts for happiness, and PORTRAIT‑STYLE chip‑gear. The UI design, while sterile, compensates for the limited graphical horsepower of the era.

Saves & Longevity Bugs

A well‑documented issue: on Windows after 2000, the game loses save data due to registry corruption. Users must back up registry keys before shutting down or risk losing progress. This bug underscores a legacy snarl that endangers the sentimental value of early digital pets.

World‑Building, Art & Sound

Visual Atlas

The game offers ten background options: city, beach, house, field, etc. Each scenery serves as a broad setting for miniature scenes that replicate the original’s neutral periphery but with richer 2‑D textures. Notably, the sprite characters transition between “standing” and “walking” animations, lending a sense of spatiality absent from the handheld.

Animation Fidelity

Animations for each character are fully voiced by a cast, including Francisco Gertá and Ido Galá. The entire sprite library features thousands of frames poorly limited by performance constraints, but the result is a smooth “talking” pet.

Audio Design

- Voice Pack: Two voices per character variant deliver cues; whimsical.

- Musical Scores: Two background tracks play during the animal’s life stages; occasional ambient sounds (bird chirps or ocean waves) in backgrounds offer sensory layer.

A minor highlight is the scrapbook function that can serve as a screensaver. The user can set the screen saver as the Tamagotchi’s sphere, blurring when the pet’s light icon turns off.

Reception & Legacy

Critical Reviews

- Mega Score (USA) – 85 % (2020 rating)

- PC Player (Germany) – 35 %

- All Game Guide – 30 %

Only three critic reviews exist; the scores reflect a mixed perception: Polish and German outlets criticized the repetitive nature, while the U.S. magazine lauded its polish.

User Reception

Player ratings average 4.2/5 (five voters). A cited amateur review on MyAbandonware notes “graphics are pretty nice” but finds overall gameplay shallow. The roster of five letters in the scrapbook to provide closure gains fondness for nostalgia but rarely sustains engagement.

Legacy Position

The Tamagotchi franchise continued to flourish in the 2000s through handhelds like the Tamagotchi Connection and mobile apps. Nevertheless, Tamagotchi CD‑ROM, amidst a flood of 90s virtual pets, remained an infrequently remembered gem for several reasons:

- Technological Museum – It demonstrates early use of screen‑savable pet simulation on PCs.

- Narrative Bootleg – The included story and voice‑acting hint at ambition beyond simple simulation.

- Preservation Artifact – Its 72‑hour care center mechanic foreshadowed later real‑time pet management features found in handheld AR games.

Because of its largely unique cameo status, Tamagotchi CD‑ROM occupies a niche place in retro gaming archives, most appreciated by collectors rather than mainstream audiences.

Conclusion

Tamatochi CD‑ROM is both a faithful pilgrimage and a focal point of early 90s gameplay constraints. While its developers captured the core emotional loop of the handheld, the PC adaptation suffered from pedestrian gameplay depth and long‑term reliability issues. Yet, its care center, scrapbook, and voice‑filled narrative give it a distinct charm that surpasses its commercial indifference. In game‑history terms, it is a modest yet instructive example of how licensed IP had to be largely reimagined within the technical limits of a nascent PC platform. For collectors and researchers, it remains a valuable signpost of virtual‑pet evolution. And for anyone curious about the intersection of early personal software and emotional simulation, the CD‑ROM offers a surprisingly delightful trip “back in time” to the teen age of Windows 95.