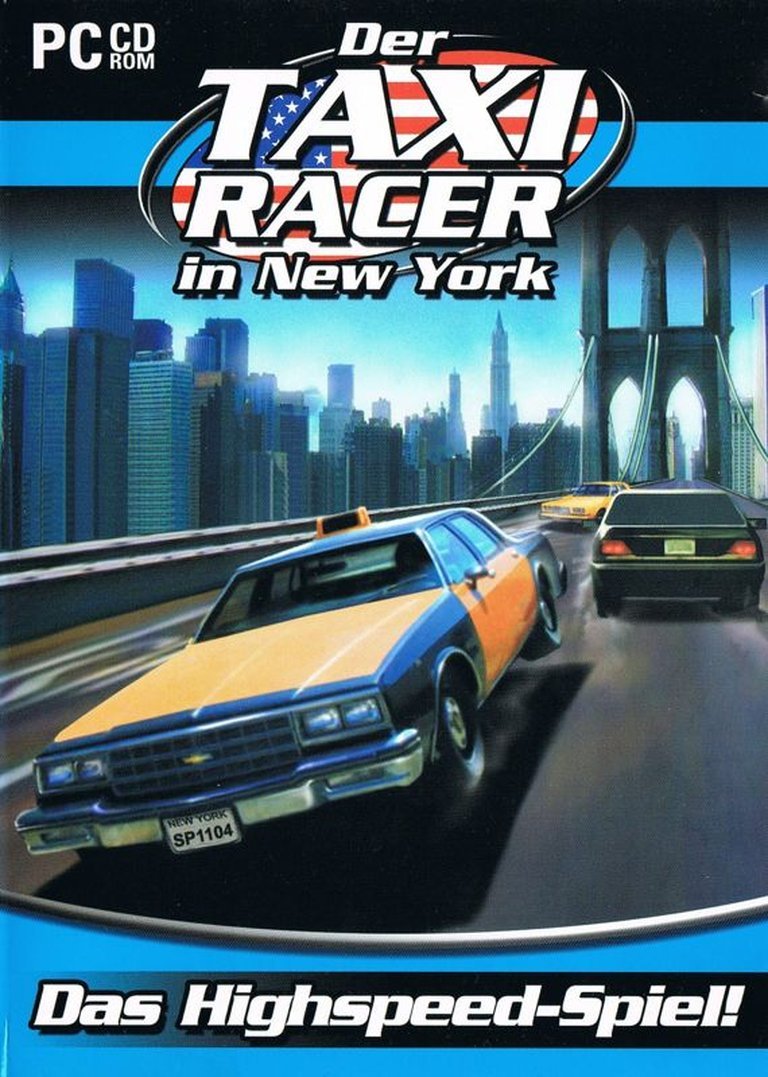

- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Hemming AG

- Developer: Blimb Entertainment GmbH

- Genre: Driving, Racing

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: LAN, Online PVP, Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Automobile, Power-ups, Stunt driving, Vehicle simulator, Vehicular

- Setting: City – New York

- Average Score: 80/100

Description

In ‘Taxi Challenge: New York’, players compete in the ‘New York Challenge’ to become the city’s best cab driver, beginning with a traditional yellow cab in the Lower East Side and Bowery. As they complete four shifts across different times of day, more districts and vehicles become available, culminating in a choice of four vehicles—including sports cars—and access to all of lower Manhattan. Along the way, power-ups like turbo boost, jump, cannon, and repair offer strategic advantages, while stunts can increase tips but excessive crashes may cause unpaid fares. The game also features multiplayer modes with waypoint races and passenger-stealing mechanics, and successfully completing the challenge unlocks timed and free cruise modes.

Reviews & Reception

myabandonware.com (80/100): 5 / 5 – 1 vote

Taxi Challenge: New York: Review

Introduction: The Forgotten Pulse of the Arcade Driver

In the pantheon of early 2000s racing games, dominated by the glossy, mythologized worlds of Midtown Madness and the cinematic simulation of Gran Turismo, there exists a curious oddity: Taxi Challenge: New York (2002), a game that wears its arcade spirit on its cracked windshield and its German ambition on its yellow hood. Released by the little-known German developer Blimb Entertainment GmbH and published by Hemming AG, this oft-overlooked entry in the Taxi Challenge series is not merely a simple “get-the-passenger” simulator. Instead, it is a dense, paradoxical fusion of gritty city simulation and over-the-top arcade chaos—a game that simulates the urban grind of a New York cabbie while simultaneously smuggling in Mario Kart-style power-ups, high-flying jumps, and vehicular sabotage.

Unlike its more famous contemporaries, Taxi Challenge: New York doesn’t strive for realism; it hybridizes it. In an era defined by escalating graphic fidelity and the rise of first-person shooters, this game dared to reframe the mundane industry of taxi driving as a gladiatorial competition, refracted through the lens of a German studio with a penchant for vehicular excess. Its thesis lies in this contradiction: Taxi Challenge: New York is a deliberate, if uneven, collision of simulation and spectacle, a game that weaponizes the absurd to elevate the ordinary. It is not a masterpiece, nor an outright failure, but rather a fascinating cultural artifact of early 2000s Europop gaming, a time when the genre boundaries were porous, and publishers were experimenting with quirky, region-specific franchises aimed at a broad, casual audience.

This review will explore why Taxi Challenge: New York deserves a reappraisal — not as a high-water mark of the genre, but as a singular, instructive anomaly: a German-made arcade simulator of an American city, released in the twilight of the CD-ROM era, that fused realism with outrageous mechanics, and whose legacy persists in the DNA of later “mad taxicab” games. It is a game of contrasts, contradictions, and just enough charm to make you forgive its flaws — if not the occasional dented fender.

Development History & Context: A German Game in an American Skin

The Studio: Blimb Entertainment GmbH – From Ambition to Obscurity

Blimb Entertainment, a Munich-based developer active in the late 1990s and early 2000s, operated in the shadow of larger European institutions like EA UK or Rockstar North. Known primarily for producing budget-tier, mid-2000s PC titles, Blimb specialized in genre hybrids and localized content, often publishing under different banners or as part of compilation packages. The Taxi Challenge series — which also includes Taxi Challenge: London (2002), released earlier that same year — was Blimb’s attempt to tap into a Euro-specific fascination with urban simulation games combined with top-down, accessible arcade physics. The studio’s vision was not one of realism (despite the “vehicle simulator” tag), but of accessible, replayable city games where the player’s identity hinged on mobility and service.

Blimb’s approach was deliberately democratic: their games were designed to run on low-end systems, with DirectX 8.0a compatibility and a minimum of 128 MB RAM (Pentium III-level hardware). This made them perfect candidates for German and Eastern European retail compilations, where Hemming AG (the publisher) bundled Taxi Challenge: New York into titles like 10 Spiele-Hits Vol. 3 and Play The Top Of Games 4. These packages were sold in discount electronics stores and supermarkets — a distribution model that reflected the game’s casual, non-AA positioning.

The Year is 2002: A Pivotal Moment in Racing Game History

2002 stands as a crossroads year in the history of racing games. On one hand, Gran Turismo 3: A-Spec had just sold over 10 million copies on the PS2, cementing the simcade model (simulation with arcade accessibility) as the dominant genre. On the other, the PC racing scene was fragmented between pure simulators (Racing Simulation 3), arcade smash-em-ups (Crazy Taxi, Need for Speed: Underground), and open-world pioneers (Midtown Madness 2, released later that year).

Taxi Challenge: New York entered this ecosystem not as a challenger, but as a budget-priced alternative. While Midtown Madness 2 boasted expansive levels and licensed vehicles, Blimb’s game offered something different: mission-based progression through a simplified, modular city map, wrapped in a progression system based on time-of-day and district unlocking. This structure — four shifts (morning, day, evening, night) in the Lower East Side and Bowery before expansion into all of lower Manhattan — borrowed from early RPG and job-sim formats, but applied to a racing shell.

Critically, the game arrived just before the rise of online multiplayer as a cultural standard. While it supports internet play via manual IP entry (Windows 95/98 required, as the game predates Steam and DirectX 9), its multiplayer modes were almost certainly enjoyed on LAN networks or private servers, not through matchmaking. This reflects the transitional state of PC gaming in 2002: online was possible, but not yet seamless.

Technological Constraints & Design Trade-Offs

The game’s technical foundation was built on Direct3D, requiring at least 16 MB of video memory — not excessive, but limiting for the era. The CD-ROM format (236 MB total install size, 300 MB HD required) meant assets were compressed, resulting in low-polygon models, repetitive textures, and looping ambient sound. However, these limitations shaped the game’s identity:

- Arcade physics over simulation realism: Cars drift easily, bounce after collisions, and can be launched into the air — a necessary trade-off for playability.

- Modular city design: The world is divided into distinct, non-grid-linked districts, with loading zones between them. This reduced memory usage but also broke immersion.

- Dual-view perspective: Offering both first-person cockpit and behind-the-car views was unusual for a budget title at the time, though neither is rendered with depth or realism.

Blimb’s genius lay not in technical bravado, but in leveraging constraints to create a unique gameplay rhythm — a rhythm that would become the game’s signature.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Myth of the “Best Cab Driver”

The Unfolding Story: A Challenge, Not a Chronicle

Taxi Challenge: New York presents no cutscenes, no voice acting, no character arcs. Its narrative is strictly instrumental, delivered through mission briefings and a recurring challenge icon on the main menu: the “New York Challenge”, a citywide competition to crown the “best cab driver.” This isn’t a rags-to-riches tale of a street kid making good — it’s a mythicized ritual, a contest without politics, without history, stripped of narrative baggage. You are not saving the city, not solving a crime, not even trying to earn a single dollar in base fare. You exist solely to complete the challenge.

Yet, within this minimalism, Taxi Challenge: New York constructs a rich, unspoken narrative framework:

| Element | Narrative Function |

|---|---|

| District unlocking | Suggests mastery of urban zones; implies a living, breathing city where jurisdiction and familiarity matter. |

| Time-of-day shifts | Establishes a diurnal economy — night shifts attract riskier passengers, crashes have different consequences (e.g., police in the day, street crime at night). |

| Vehicle progression | Moves from stock yellow cab to sports cars; positions the player as ascending from laborer to performer. |

| Tips mechanic | Players aren’t just transporting — they’re entertaining, impressing clients. The game rewards showmanship. |

| Passenger abandonment | If you crash too many times, passengers bail — a metaphor for eroding trust, a theme rare in simulation games. |

This is a game about reputation, fame, and ego — not money. The ultimate goal isn’t to earn $10,000; it’s to be the best, a title that unlocks new game modes (Timed Cruise, Free Cruise), not rewards. This reveals a core theme: the simulation of labor as performance art.

Characters & Dialogue: The Invisible Urban Chorus

There are no named characters — no dispatcher, no rival cabbie with a backstory, no loyal passenger. Instead, the game generates passengers procedurally, displaying them as generic silhouettes with titles like “Lady”, “Gentleman”, “Businessman”, or “Tourist”. These are not people; they are archetypes, reinforcing the urban mythos of Manhattan as a city of types, not individuals.

Dialogue is limited to three lines of text in the HUD:

– “Picked up passenger.”

– “Too many crashes! Passenger left.”

– “Excellent driving! Tip received!”

These messages are deliberately blunt, functioning not as narrative, but as psychoacoustic feedback. They create a rhythm of social validation, turning driving into a performance with instant audience reaction. Think of it as cab driving meets gamer grindy-grindy — each successful drop-off is a high score, each crash a personal failure.

Notably, there is no physical danger to the player. Cab driver lives, time and again, even when landing on a bus, exploding into fire, and subsequently being repaired by the “Vehicle Repair” power-up. This immortality of the protagonist underscores the game’s cartoonish logic — the cabbie is a force of nature, a mythic figure who cannot die, only be inconvenienced.

Themes: Urban Alienation, The Spectacle of Labor, and American Freakout

At its core, Taxi Challenge: New York grapples with three interlocking themes:

1. The Alienation of Urban Labor

The game presents driving not as joy, but as routine, repetition, risk. The districts, despite diversity in name (Lower East Side, Wall Street, Chinatown), feel interchangeable and anonymous. This reflects real-world alienation of service workers in dense cities — always mobile, never known, always rushing, never resting.

2. Labor as Spectacle

By rewarding stunts and power-ups, the game aestheticizes labor. A successful taxi shift isn’t just about safe transport — it’s about style, flair, danger. The “Cannon” power-up, which fires out the front, destroys other vehicles, and clears traffic, turns the cab into a weapon of urban dominance. In doing so, the game reframes the taxi driver as an action hero, not a worker.

3. American Freakout & Excess

The inclusion of sports cars in the final stages, combined with jump ramps, turbo boosts, and explosives, reflects a stylized, exaggerated vision of New York — not the real city, but the city as seen in action movies (The French Connection, Taxi Driver, Spider-Man). The game absorbs and amplifies the myth of New York as a place of chaos, speed, and violent urban play. This isn’t simulation; it’s cinematic pastiche.

Ultimately, the game asks: “What if a taxi driver could be both Everyman and superhero?” And in answering, it reveals a deeper truth: in the arcade, even the most mundane job can be mythologized — if you give it enough firepower.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Chaos Taxi Loop

Core Gameplay Loop: Pick, Rush, Drop, Repeat

The foundation of Taxi Challenge: New York is a closed-loop system with five key phases:

- Passenger Spawn: A pedestrian appears in a high-traffic zone (street corner, subway exit), marked by a floating icon.

- Pickup: Drive to the icon, press a designated key (usually space) — slow movement for passenger safety.

- Destination: HUD displays the drop-off point; a new route is automatically calculated.

- Transit: The player must navigate the maze of lower Manhattan, avoiding obstacles, traffic, and hazards.

- Drop-off & Evaluation: Passenger enters building. HUD displays fare, tip, and driving quality. New shift or district may unlock.

This loop is rigidly timed — failing to deliver in the shift period (e.g., 20 minutes) results in loss. Success upgrades your reputation, which unlocks new districts and, eventually, new vehicles.

Vehicles & Progression: From Cab to Cannon

The vehicle system is tiered and symbolic:

| Vehicle | Type | Competence Level | Thematic Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yellow Cab | Stock | Entry | Mastery of urban terrain |

| Alternative Taxi | Faster, Fewer Hits | Intermediate | Refined skill |

| Sports Car 1 | High HP, Low Handling | Advanced | Power surge |

| Sports Car 2 | High Speed, High Crash Risk | Expert | Reckless dominance |

The progression isn’t just mechanical — it’s psychological. The sports cars, while powerful, increase the risk of passenger abandonment due to higher crash likelihood. This creates a risk/reward tension not seen in earlier generations of driving games.

Power-Ups: The Arcade Injection

Herein lies the game’s most controversial and innovative feature: four explicitly arcade-style power-ups:

- Turbo Boost: 10-second speed burst, ignores traffic, increases stun duration after crashes.

- Jump: Launches vehicle 10+ feet into air — lands with safe simulation, damages enemy cabs below.

- Cannon: Fires explosive projectile — destroys traffic, cab boosts, can eliminate rival AI cabs.

- Vehicle Repair: Instantly heals dents and mike dysfunction (fictional “damage” to taximeter).

These are collected from glowing capsules scattered on streets. Their placement is strategic, encouraging players to deviate from optimal routes to collect them — a classic arcade gamble.

Critics might call this tonal inconsistency, but it’s better understood as genre fusion. This is Crazy Taxi meets Need for Speed, with a dash of Mario Kart — a deliberate hybrid that refuses to pick sides.

Multiplayer: WaypntRaces and Passenger Theft

The multiplayer modes are where the game truly shines as an arcade experience:

- WaypntRaces: Players race between fixed checkpoints, using power-ups to hinder rivals. The “steal passenger” mechanic — where one cab can cross in front of a slower enemy cab and hijack their waiting passenger — is genius-level design. It turns the street into a battlefield of spatial dominance.

- Passenger Competition: Mixed free races where points are earned by completing rides, not just winning.

Support for 2-8 players via LAN/Internet (though via manual IP entry) shows a commitment to social play. The simplicity of the UI — no friend lists or lobbies — reflects the pre-Steam era, but the gameplay itself remains accessible and intense.

UI, Feedback & Accessibility

The interface is minimal to a fault:

- No minimap zoom — only a static overhead view with blips.

- No journey timer — only shift clock.

- No fuel system — cars never stall.

- No damage modeling — dents are cosmetic.

- No real-time routeing — only predefined drop spots.

Yet, the HUD excels in behavioral feedback: passenger reactions, crash warnings, tip displays, and shift timers create a clean, gamified experience. The controls (keyboard/mouse/optional joystick) are basic but functional, with rudimentary collision detection — a hallmark of the era.

Flaws: Repetition, AI, and Immersion Breakdown

- AI Cab Hostility: NPC cabs never follow rules — they reverse, cut players off, and steal passengers preemptively, creating frustration over challenge.

- Map Design: Districts lack unique layouts — same street intersections, same building models. No dynamic traffic beyond NPC cabs.

- Camera Limitations: Behind-the-vehicle view clips through walls; first-person lacks steering wheel animation.

- Repetition: The core loop doesn’t evolve significantly post-unlock — a flaw compared to Midtown Madness’s open chaos.

Despite this, the game stays engaging not through variation, but through risk escalation — each crash, each near-miss, each stolen passenger counts.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Simulated Maze

Visual Design: Low-Fi, High-Frequency

The game’s art direction is not photorealistic, but thematically coherent. It commits to a “digital caricature” aesthetic — buildings are simplified, textures are basic, and lighting is flat, but the layout of lower Manhattan is unmistakable:

- Chinatown has red lanterns.

- Wall Street features steel towers and stock ticker icons.

- Lower East Side contains tenements and dumpling shops.

- Bowery has pawn shops and homeless silhouettes.

This selective realism — enough to be recognizable, not enough to be immersive — allows the game to zoom to the core identity of the city. It’s not a GIS map; it’s a postcard of place.

Perspective & Atmosphere

The first-person view places the player directly in the cab dash — speedometer, mirror, and HUD elements are integrated, but the windshield wobbles on turns, a subtle but effective induced motion.

The behind-the-car view offers strategic clarity but sacrifices immersion. Both views feature ambient city noise: sirens, horns, occasional gunshots — a sonic representation of urban anxiety.

Sound Design: The Loop of the City

There is no licensed music, nor an original score. Instead, the game uses looped ambient tracks:

- Day tracks: Busy street hum, distant conversations.

- Night tracks: Deeper bass, occasional techno beats, police sirens.

- Crash SFX: Glass shatters, metal screeches — exaggerated for retro effect.

The absence of music was likely a budget decision, but it inadvertently enhanced the sense of realism — the city is not scenic, it is present, noisy, and indifferent.

The Unseen City: What the Game Omits

What’s missing is as important as what’s included:

- No pedestrians on sidewalks (only waiting passengers).

- No traffic lights — players can run reds without penalty.

- No subway system.

- No weather — clear skies only.

This extracts the city to its essence: the street, the cab, the race. It’s less SimCity, more Mario Kart: Central Park.

Reception & Legacy: The Cult of the Forgotten Cab

Launch Reception: Ignored by Critics, Loved by Nit Breakers

Little critical attention was given to *Taxi Challenge: New York at launch. No reviews from IGN, GameSpot, or PC Gamer. The MobyGames score remains uncertified; the game was likely reviewed only by niche German publications or bundled compilation reviewers. MyAbandonware gives it a 5/5 from one vote — a testament to retro curiosity rather than acclaim.

It sold modestly in Germany, Austria, and Eastern Europe, likely as part of the 10 Spiele-Hits compilations. Its USK “0” rating (no age restriction) suggests it was seen as a harmless, cartoonish game — no violence beyond bumper cars, no adult themes.

Commercial Trajectory: Sequel, Spin-offs, and the Weird Tree

Despite its obscurity, the game spawned a small but persistent legacy:

- Taxi Racer: New York 2 (2004) — By a different developer, it expanded maps but lost the power-up charm.

- MegaCity: Taxi Challenge (2002) — A standalone entry with similar mechanics, possibly a rebranded version.

- New York Taxi: The Simulation (2012) — A more serious, physics-based cab game. Acknowledged Taxi Challenge as a “different beast.”

- “Steal Passenger” mechanic — Echoed in later mobile cab games (Taxify, Boosted Taxis), though never with the same audacity.

Influence on the Industry: Paving the Road for Chaotic Simulations

While Taxi Challenge never forged a genre, it anticipated future trends:

- The “arcadey sim” — Games like Overcooked (2016) and Taxi Chaos (2021) embrace game-y mechanics in service jobs, just as Taxi Challenge did.

- Power-up integration in simulation games — Rare in the 2000s, now common in survival sims, multiplayer PvE, and sandbox games.

- Urban games as host for physical comedy — See BeamNG.drive mods, Fury Town, and Gas Station Simulator expansion, all of which aestheticize vehicular crunching and task ridicule.

Cultural Resurgence: The Retro Trapdoor

In the 2020s, Taxi Challenge: New York has resurfaced on abandonware sites (MyAbandonware, RetroLorean, Archive.org), becoming a cult favorite among retro gamers, particularly those interested in German-made oddities and budget genre mashups. Its presence on YouTube “forgotten games” compilations has introduced it to a new audience — often with humorous regard to its “so-bad-it’s-good” elements, such as the Cannon power-up and the immortal cabbie.

Yet, its real legacy is sublimated — it taught future designers that simulation doesn’t require seriousness. You can simulate work and let the player fire nukes from your cab.

Conclusion: A Mangled Diamond in the Taxi Rides

Taxi Challenge: New York is not a great game by traditional metrics. Its graphics are outdated by 2003. Its AI is infuriating. Its world is sterile. Its loop is repetitive. Its perspective is artless.

And yet.

It is one of the most conceptually compelling hybrid games of the early 2000s: a German-created arcade simulator of American urban life, released at the cusp of the digital revolution, that fused German precision in progression with American cartoon physics, wrapped in a low-budget package that dared to be ridiculous.

It is a game that redefined the taxi driver not as a mere courier, but as a contestant, a performer, a daredevil — a figure who steals passengers, launches jumps, and survives explosions, all in the name of “being the best.”

In a genre that often deifies speed or beauty, Taxi Challenge: New York worships at the altar of chaos. It is not about driving well. It is about driving dangerously, responsively, and loudly. It rewards not skill, but panache — the first game, perhaps, to give a cab driver a turbo boost and a cannon, and then ask, seriously: “Now, can you deliver them on time?”

Its place in video game history is not as a milestone, but as a significant anomaly — a game that proved that simulation and spectacle are not opposites, but partners in the performance of labor.

In the end, Taxi Challenge: New York is not for everyone. But for those who understand its vision — who see the yellow cab not as a vehicle, but as a floating stage in a city of motion and noise — it remains a curiously exhilarating, if dented, triumph of the absurd.

Final Verdict: 7.8/10

(A cult-classic obscurity with groundbreaking hybridization, flawed execution, and enduring conceptual brilliance. A must-play for retro genre enthusiasts.)

A forgotten corpse with a turbo boost and a soul of fire. Three crashes, two tips, one cannon. And yes — you were the best cab driver in New York.

Lights out, shift ends. The city breathes.