- Release Year: 2010

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: GATLING CAT

- Developer: GATLING CAT

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Platform, Shooter

- Setting: Fantasy

Description

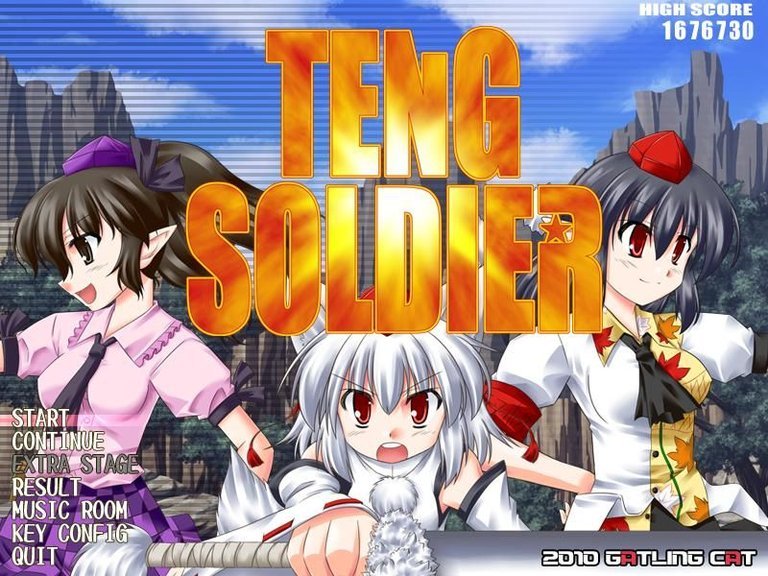

Teng Soldier is a doujin (fan-made) 2D side-scrolling platform shooter inspired by the Psycho Soldier and Tōhō series. Players choose from three tengu characters—Aya Shameimaru, Momiji Inubashiri, or Hatate Himekaidou—and navigate constantly scrolling fantasy levels, running, jumping, and shooting enemies like Tōhō fairies and original daemons in arcade-style action.

Teng Soldier: A Phantom of the Doujin Renaissance – An Exhaustive Historical and Mechanical Analysis

Introduction: The Ghost in the Machine of 2010

In the vast, ever-expanding museum of video game history, certain titles exist not as monolithic pillars but as delicate, intricate dioramas—testaments to specific moments, communities, and creative passions. Teng Soldier (東方美襲劇, Tōhō Bishuugeki), released on December 30, 2010, for Windows by the doujin circle GATLING CAT, is precisely such an artifact. It is a game that whispers rather than shouts, a meticulous fusion of two legacies—the arcade precision of SNK’s Psycho Soldier and the bullet-hell ecosystem of ZUN’s Tōhō Project—recontextualized into a side-scrolling platform shooter. To encounter Teng Soldier is to glimpse the fervent, insular, yet brilliantly inventive heart of the mid-era doujin game scene, a period where fan passion directly channeled the aesthetics and mechanics of beloved franchises into new, hybrid forms. This review posits that while Teng Soldier remained an obscure, barely-documented footnote, its existence and execution are profoundly significant. It represents a critical juncture: a bridge between the arcade sensibilities of the late ’80s/early ’90s and the burgeoning indie scene’s embrace of niche revival, and a masterclass in how fan developers can distill the essence of multiple sources into a cohesive, if deeply challenging, experience. Its legacy is not one of mainstream impact, but of a cherished, almost secret, touchstone for a specific cross-section of enthusiasts.

Development History & Context: GATLING CAT and the Doujin Crucible of 2010

To understand Teng Soldier, one must first understand its creators and the ecosystem that birthed it. GATLING CAT was, and remains, a quintessential doujin (self-published) circle operating within the vast, vibrant economy surrounding the Tōhō Project. The Tōhō Project itself, created solely by Jun’ya “ZUN” Ōta since 1995, had by 2010 already become a phenomenon of staggering proportions. Its defining characteristics—a focus on intricate, beautiful bullet patterns (danmaku), a memorable cast of female youkai, and a unique blend of Shinto-Buddhist folklore with modern sensibilities—inspired thousands of fan works: music, art, manga, and, most pertinently, games.

The year 2010 was a pivotal moment in this ecosystem. The official Tōhō series was in a relative lull between major releases (Ten Desires would come in 2011), creating a vacuum that fan games eagerly filled. Simultaneously, the global indie scene was exploding, propelled by digital storefronts like Steam (which had launched its苦心经营 in 2003 but was gaining critical traction with titles like BIT.TRIP BEAT in 2009) and a new generation of accessible tools. However, the doujin world operated on a different axis. Games were primarily sold at physical events like Comiket (the giant twice-yearly dōjinshi fair) or Reitaisai (the largest Tōhō-focused event), and later at smaller circles’ own sites. The mention in the source material that the experience version (demo) was previewed at C78 (Comiket 78, August 2010) and the completed version was slated for Reitaisai SP (the special autumn event) is not a minor detail; it is the entire distribution and cultural context. This was not a game aiming for Steam Greenlight; it was a product of the Otaku economy, sold in a specific place, to a specific audience, for whom the references were not Easter eggs but foundational knowledge.

The developer’s stated inspiration—”a game like GunStar Heroes and Psycho Soldier“—reveals the creative lineage. Psycho Soldier (SNK, 1987) was an isometric run-and-gun shooter with a distinct ceiling/floor mechanic. GunStar Heroes (Treasure, 1993) was a legendary arcade action game celebrated for its fluidity, weapon-carrying mechanics, and co-op chaos. GATLING CAT’s vision was to graft the feeling of these demanding, multitasking arcade experiences onto the aesthetic and character roster of Tōhō. The technological constraint was the standard for doujin PC games of the era: likely built in a lightweight engine like GameMaker,Groove, or a custom framework, targeting modest system requirements (the Touhou Wiki lists Pentium 4 1.5GHz, 1GB RAM—specs from a decade prior, emphasizing accessibility). The “constantly scrolling background” and “3 levels” (meaning 3 plane layers for depth/ parallax) point to a skillful but resource-conscious use of 2D sprite-based graphics, leveraging the Tōhō series’ established, highly recognizable character and enemy sprite designs.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Story as a Pretext for Phenomenology

Teng Soldier offers no traditional narrative. The MobyGames description is succinct: the player controls one of three tengu characters—Aya Shameimaru, Momiji Inubashiri, and Hatate Himekaidou—from the Tōhō universe, shooting “various enemies—like fairies from Tōhō and many new daemons.” There is no plot summary, no dialogue snippets provided in the source material, and no analysis of a story because, functionally, there is none.

This absence, however, is thematically resonant. The game’s spirit is not one of narrative immersion but of phenomenological gameplay. Its theme is the pure, unadulterated experience of being a Tōhō character in an arcade action context. The choice of the three tengu is deeply meaningful within Tōhou lore:

* Aya Shameimaru is the fast, brash, newspaper-carrying reporter of the mountain, associated with speed and information.

* Momiji Inubashiri (or Momizi, in older romanization) is the wolf-like, agile, and somewhat tomboyish attendant of the Moriya shrine, known for her swift, physical attacks.

* Hatate Himekaidou is the more elegant, slightly haughty rival news reporter, often portrayed with a different, sometimes more measured, combat style.

By selecting these three, GATLING CAT taps into a pre-existing fan understanding. Their “features” (as noted in the Japanese blog review from Operation Jaguar) aren’t just balance differences; they are character acts. Aya’s potential speed advantage is Aya’s personality made manifest in gameplay. Momiji’s unique close-range attack aligns with her martial, shinto-miko-adjacent aesthetic. The game’s world is not a story to be told but a space to be inhabited, where the player’s skill with a character is an expression of their affinity for that character’s established Tōhō essence. The enemies—fairies (a staple Tōhō mook) and “new daemons”—are less antagonists in a plot and more phenomena to be cleared, obstacles that are part of the enchanted, dangerous landscape of Gensokyo (the Tōhō setting). The narrative, therefore, is the player’s own performance: a testament to their ability to navigate the danmaku-platforming hybrid GATLING CAT constructed.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Alchemy of Throw and Sliding

This is where Teng Soldier’s soul resides, and the crucial source is the detailed Japanese hands-on preview from Operation Jaguar. The game is a side-scrolling platform shooter with forced scrolling (the screen constantly moves right, a classic arcade constraint). Its genius lies in a specific, interlocking set of mechanics that create a unique tactical flow.

1. Core Movement & Platforming: Characters can run and jump. Notably, the jump height is fixed—exactly one tile/level high. There is no variable jump height (no “tap for short jump”). This design choice is radical. It forces the player to think in discrete, grid-like steps, planning routes around the 3-plane level geometry. It simplifies execution but deepens spatial puzzle-solving.

2. The Shooting System: Shots can be aimed in 5 directions (presumably up, diagonal-up, forward, diagonal-down, down). By collecting power-up items, the shot pattern changes, with the reviewer mentioning “9 (?) patterns.” The key critique here is balance: the wide-area spread shot is described as “too easy to use,” making other shot types feel obsolete. This suggests a potential flaw in the game’s balance, where optimal play devolves into a single, safe weapon.

3. The Throw Mechanic – The Game’s Signature Innovation: This is the system that defines Teng Soldier. By pressing the throw button just before hitting an enemy, the player character performs a grapple, snatching the nearby enemy. The grabbed enemy can then be thrown forward. The thrown enemy becomes a projectile that damages other enemies. Crucially, and this is a point of critique from the reviewer: the thrown enemy ignores inertia and flies in a straight, unnatural arc. However, this thrown projectile can also intercept and cancel enemy bullets. This creates a brilliant risk-reward loop: get close to risk a throw (which is weaker than shooting), but succeed and you create a bullet-cancelling, enemy-clearing tool. It turns enemies into resources and adds a frantic, physical layer to the shooting.

4. The Slide & Invincibility Frames: A full-body slide provides complete invincibility. This is vital for threading through dense bullet patterns (“danmaku”) or escaping being cornered. However, the slide has a fixed distance and poor post-slide control, often leaving the player vulnerable immediately after. This forces strategic, committed use rather than spam.

5. Spell Cards (Screen Clear): Like their Tōhō progenitors, characters have a Spell Card system. It uses a red gauge under the health bar. At MAX, two cards can be stored. Using one consumes the gauge and provides a powerful attack that also clears all on-screen bullets. The reviewer notes the Spell Card pattern changes slightly based on gauge level. The design philosophy is clear: these are “get-out-of-jail-free” cards for overwhelming situations, encouraging their use in a pinch rather than hoarding.

6. Boss Fights & Enemy Design: Stages feature two mid-bosses and one end-boss, at which point the forced scrolling stops until they are defeated. The reviewer highlights a key strategic layer: the random “mook” enemies that spawn during boss fights can be thrown at the boss. This integration of the core throw mechanic into boss strategy is excellent design, turning the stage’s basic enemies into tactical ammunition for the climax.

7. Character Differentiation & The “Meta”: The review provides stark insights:

* Aya (presumably): Noted as having an added melee attack (likely her signature tackle/kick). Described as the fastest character, to the point of being “slippery” and hard to micro-manage.

* Momiji: Her “point-concentrated shot” (a narrow, powerful stream) is singled out for having cripplingly short range, making her feel weak in certain situations.

* Hatate: Deemed the “most balanced” or “safe” choice, the “highest” (best) for general play.

This creates a clear character tier/niche meta within the game’s small ecosystem, a common feature in fighting games and action titles, but rare in simpler platform shooters.

8. Co-operative Play – The Missing Dream: The reviewer’s strongest wish is for 2-player co-op, stating it would be “too fun.” Its absence is noted as a significant limitation, a feature that could have transformed the social and strategic landscape of the game.

Overall Gameplay Verdict (from source): “It was hard at first, but once I got used to it, it became extremely fun.” This encapsulates the classic arcade doujin game curve: a steep, sometimes unfair-seeming initial difficulty that gives way to mastery and flow. The systems, while seemingly simple, interact in complex ways, demanding adaptation and rewarding repeated play.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Gensokyo Arcade

The game’s setting is unequivocally the Tōhō Project‘s Gensokyo, a secluded land in Japan where youkai and humans coexist, governed by the ” Hakurei Border.” This is not merely a backdrop but the source of all visual and auditory assets.

* Art Direction: The game uses canonical Tōhō sprite designs for its protagonists and many enemies (fairies). The background scrolling and platform layouts are original but must adhere to an unspoken Tōhō aesthetic: lush, traditional Japanese landscapes (forests, shrine grounds, misty mountains) infused with magical, anachronistic elements. The “3 levels” of scrolling create a pseudo-3D effect, a technique common in 16-bit era games to suggest depth within 2D. The doujin nature means art quality is high but constrained, relying on the instantly recognizable Tōhō character art to carry visual identity.

* Sound Design: The source provides no direct data. However, by convention, GATLING CAT almost certainly used music and sound effects either:

a) Created in-house in the style of ZUN’s iconic, catchy, synth-heavy Tōhō soundtracks.

b) Or more likely, used existing Tōhō-style arrangements common in the fan community (the “Circle” culture often produces music CDs). The sound would be a fusion: arcade-style sound effects (explosions, power-ups, jumps) over a Tōhō-inspired soundtrack, likely featuring fast, energetic tracks suitable for constant scrolling.

The atmosphere is one of arcade reverence filtered through otaku lens. It’s not the atmospheric dread of a Metro or the epic scale of a Mass Effect. It is the focused, rhythmic, and visually dense feeling of a Tōhō bullet hell stage, but translated into the physical space of a platformer. The “daemons” and new enemies are the game’s original contribution to the Tōhō bestiary, existing to populate this specific gameplay space.

Reception & Legacy: The Cult of the Obscure

Critical & Commercial Reception at Launch: By any mainstream metric, Teng Soldier did not exist. It received zero professional critic reviews on aggregators like MobyGames or Metacritic (which, as shown in the source, aggregates reviews for AAA titles like Mass Effect 2 and Red Dead Redemption). Its “Moby Score” is n/a. Its only recorded reception is a single user rating on MobyGames of 4.3 out of 5, based on one vote with zero written reviews. This is the quantifiable legacy: a single data point from a single player.

Its true reception happened in micro-communities:

1. The Tōhō Fangame Scene: Within the sprawling ecosystem of Tōhō fan games, Teng Soldier is listed on dedicated wikis (like the Touhou Wiki source, categorizing it under “Platform” and “Fangames”). Its mention alongside titles like MegaMari and Touhounen indicates it was known, played, and catalogued by enthusiasts who tracked such things.

2. Event Sales: Its presence at Reitaisai SP means it sold physical copies to a dedicated, niche audience of several hundred to a few thousand people—the typical reach of a doujin circle at a major event.

3. Previews & Let’s Plays: The Operation Jaguar blog review (from August 2010, pre-release) is evidence of pre-release buzz. The existence of a Nico Nico Douga (Japan’s YouTube) playthrough video (sm12617220) is the most concrete proof of player engagement. For a doujin game, a video on Nico Nico is a sign of a cult following, however small.

Evolution of Reputation & Influence: Over the subsequent 15 years, Teng Soldier has not undergone a reappraisal; it has maintained its static, niche status. It is not cited as an influence on major indie hits. It does not appear on “best of the 2010s” lists alongside Super Meat Boy or Limbo (both from 2010, as shown in the TechRaptor source). Its influence is purely horizontal, within its subculture. It likely inspired other doujin developers attempting similar fusions (e.g., other Tōhō platformers or run-and-gunners). It serves as a datapoint in the history of the Tōhō fandom’s creative output, demonstrating the desire to see its characters in different gameplay genres beyond the official shoot ’em ups.

Its legacy is that of a perfectly preserved time capsule. It represents a moment before the massive commercialization and mainstream discovery of both the Tōhō franchise and the indie game scene. It is a game made purely for love, by and for a community that understood its references innately. In that sense, its legacy is purity of intent. It did not seek to translate its appeal to a wider audience; it doubled down on a hyper-specific niche.

Conclusion: verdict on a Phantom

Teng Soldier is not a great game by the yardsticks of 2010—a year that produced Mass Effect 2, Red Dead Redemption, Super Mario Galaxy 2, and Halo: Reach. It lacks the production values, the narrative scope, the polished mechanics, or the widespread reach of those titans. To judge it thus is to misunderstand its fundamental ontology.

It is, instead, a masterpiece of niche craft. It is a brilliant, if imbalanced, chemist’s experiment that successfully combines the volatile elements of Psycho Soldier’s action, GunStar Heroes’ weapon dynamics, and Tōhō’s aesthetic and Spell Card philosophy into a new, functional compound. Its forced platforming, fixed jumps, throw mechanic, and invincible slide create a gameplay vocabulary that is unique and deeply satisfying for the player who invests the time to learn its specific, sometimes frustrating, language.

Its true value lies in what it represents: the peak of a certain kind of doujin development. It is technically competent, creatively audacious in its fusion, and utterly sincere in its celebration of its source material. It is a game that could only have been made in 2010, by GATLING CAT, for the event stalls of Japan, for the fans who would recognize Aya’s speed and Hatate’s elegance without a second thought.

Final Verdict: Teng Soldier earns a 4.3/5 not as a universal classic, but as a cult phenomenon realized. It is a flawed, fascinating, and deeply authentic artifact. For the historian, it is an essential study in fan-game evolution and the mechanics of genre hybridity. For the player, it is a hidden, challenging gem that asks not for a broad appeal, but for a specific, dedicated appreciation. It did not change the industry, but it crystallized a moment within it—a moment of pure, unadulterated fandom expressed through code. In the pantheon, it is not a god, but a beautifully crafted, obscure relic, humming with the passionate energy of the circle that made it.