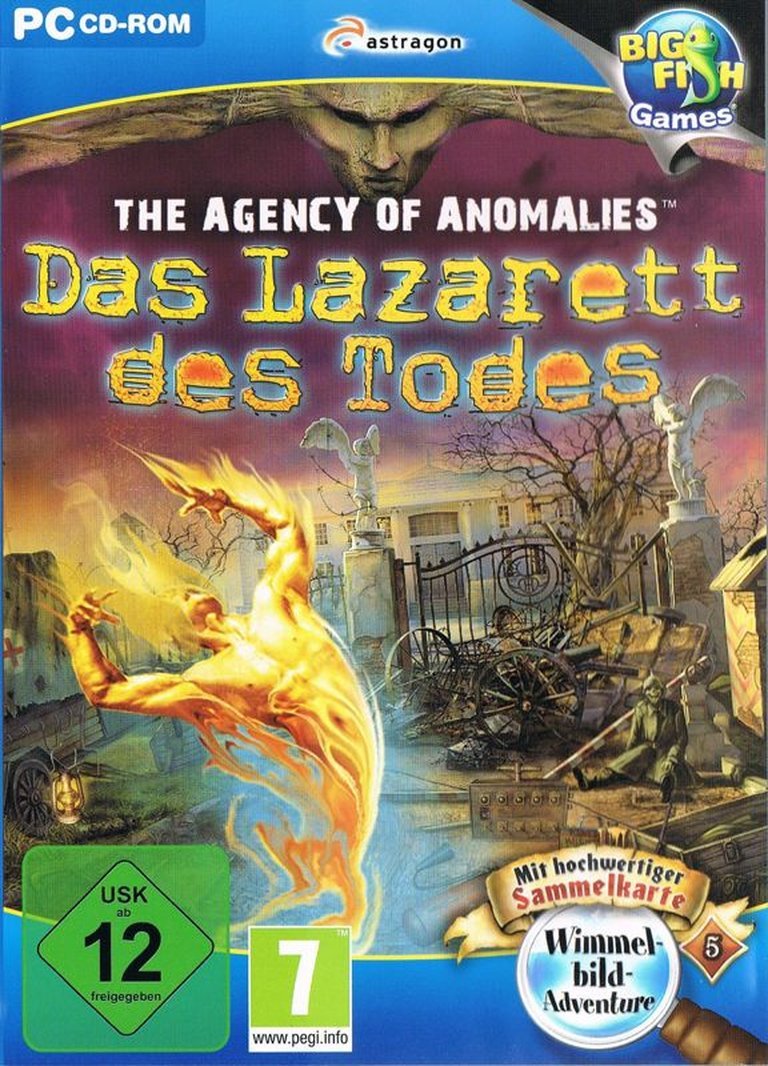

- Release Year: 2012

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Big Fish Games, Inc

- Developer: Orneon

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 1st-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Hidden object, Mini-games

- Setting: Detective, Horror, Mystery

Description

The Agency of Anomalies: Mystic Hospital is a hidden object adventure game set in a clandestine government laboratory established within an old hospital. After secret experiments to create super soldiers go awry, five soldiers transform into deadly monsters, and players must explore the eerie facility, solve intricate hidden object puzzles and mini-games to track down and eliminate each anomalous threat.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy The Agency of Anomalies: Mystic Hospital

PC

The Agency of Anomalies: Mystic Hospital Guides & Walkthroughs

The Agency of Anomalies: Mystic Hospital Reviews & Reception

gamezebo.com : The Agency of Anomalies: Mystic Hospital is far from just another HOG cliche.

jayisgames.com : Mystic Hospital is a fairly tame game, and you’ll find very little here that would even passably qualify as scary.

The Agency of Anomalies: Mystic Hospital: A Definitive Review of a Casual Gaming Masterpiece

Introduction: The Haunting of Obscurity

In the vast, often maligned cemetery of casual gaming—a genre frequently dismissed as ephemeral fleeceware—certain titles achieve a curious dual existence: critically adored by their dedicated niche yet invisible to the broader historical canon. The Agency of Anomalies: Mystic Hospital (2012) is one such phantom. Developed by the now-defunct Orneon Games and published by Big Fish Games, this hidden object puzzle adventure (HOPA) emerged during the golden age of the casual boom, yet today it languishes with a mere four collectors on MobyGames and no aggregated critic score. Its obscurity is a profound injustice. This review argues that Mystic Hospital is not merely a competent entry in a crowded genre but a meticulously crafted, narratively cohesive, and mechanically sophisticated title that represents the artistic and design peak of early-2010s HOPA design. Through an exhaustive analysis of its development, narrative, gameplay systems, and atmospheric construction, we will establish its rightful place as a canonical work of interactive storytelling—a darkly beautiful, substantially deep experience that transcended the formulaic constraints of its time.

Development History & Context: Orneon’s Swan Song in the Casual Pantheon

To understand Mystic Hospital, one must first understand Orneon Games. The studio, active primarily between 2009 and 2014, was a prolific but low-key producer of HOPA titles for Big Fish Games, the dominant digital distributor of the era. Their previous work included Detective Agency (2009) and Paranormal Agency (2008), establishing a pedigree in mystery and the supernatural. Mystic Hospital, released in February 2012 for Windows, was their first foray into a longer-form, serialized narrative structure, birthing the Agency of Anomalies series that would culminate in four titles before Orneon’s dissolution.

The game’s technological and market context is critical. 2012 was the zenith of the casual boom, with Big Fish Games’ model of episodic, story-driven HOPAs dominating a multi-million-dollar market. The constraints were clear: fixed, flip-screen visuals (a legacy of scalable design for varying hardware), 2D pre-rendered art, and a business model built on trial-to-purchase conversions. Yet within these confines, Orneon demonstrated remarkable ambition. The game’s system requirements—a 1.0 GHz processor, 1.28 GB RAM—were minimalist, but the art asset density was high. The inclusion of a “Collector’s Edition” with a sprawling bonus chapter (over two hours of gameplay, as noted by Gamezebo) was a direct response to player demand for value, a trend Big Fish championed.

Orneon’s vision, as inferred from the final product, was to elevate the HOPA from a passive scavenger hunt to an active investigation. The core mechanic—the Anomalous Activity Detector (AAD)—was a design innovation that softly guided without hand-holding, a “radar” that highlighted interactive zones, as detailed in the Big Fish walkthrough. This respected player agency while mitigating the genre’s infamous “random clicking” frustration. The decision to frame the entire experience as a case file for “The Agency of Anomalies” provided a diegetic justification for the hidden object lists, notebook objectives, and “Top Secret Files,” weaving the UI directly into the narrative fabric—a subtle but profound achievement in genre integration.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Anatomy of a Scientific Horror Saga

Mystic Hospital’s narrative is its most lauded and developed aspect, standing head and shoulders above the generic “haunted house” plots common to the genre. The premise, as delivered in the opening cutscene and chronicled in the Top Secret Files, is a tightly wound tragedy of scientific hubris: post-Great War (WWI) government-funded experiments to create super-soldiers using a paranormal serum. The projects overseen by the eponymous Dr. Odin Dagon resulted not in empowered warriors but in five distinct, tragic monstrosities, each a perversion of a soldier’s identity and a specific anomalous ability:

1. Alexander Sylvani (The Lightning Man): A victim of electro-paranormal fusion,他的存在 itself generates lethal electrical arcs.

2. Eric Weissman (The Invisible Man): His condition is tied to telekinetic distortion, making him unseen and capable of object manipulation.

3. Lynden Beck (The Burning Man): A pyrokinesis subject, perpetually wreathed in supernatural flame.

4. Chris (The Ice Man): Cryogenic or thermal negation powers, encasing his surroundings in ice.

5. Karl Lycaon (The Werewolf): A bestial transformation, the most classic horror archetype reinterpreted as a failed super-soldier.

The protagonist is an agent of the mysterious “Agency of Anomalies,” contacted by the sole surviving scientist, Dr. Oliver Orvos. The MacGuffin is the Nexus, a device capable of containing and stabilizing the volatile paranormal energy (“anomalous energy”) leaking from the monsters and, if unchecked, threatening to tear open a dimensional vortex. The narrative structure is cleverly cyclical: each chapter focuses on neutralizing one monster, achieved not through combat but through investigative puzzle-solving that culminates in using the Nexus Tube to absorb their residual energy. This reframes “combat” as a form of clinical containment, reinforcing the game’s themes of scientific responsibility.

The dialogue, while sparse, is effective. The monsters are not mindless beasts but tormented souls; the walkthroughs note that clicking on skeletons, paintings, and inanimate objects yields “interesting reactions,” implying a lingering consciousness. The true antagonist, Dr. Dagon, is a silhouette of ambition—his name an explicit nod to Lovecraftian cosmic horror (Dagon, the Deep One), tying the scientific horror to a more ancient, unknowable evil. The final confrontation is not a physical battle but a complex, multi-stage puzzle involving the reassembly of nameplates and the alignment of energies within a ritual chamber, symbolizing the restoration of order to a broken system.

Thematically, the game is a treatise on the ethics of experimentation, the victims of militarized science, and the bureaucratic effort to clean up such messes. The hospital, a former military installation turned secret lab, is a perfect metaphor: a place of healing turned into a factory of suffering. The player’s role as an “Agent” places them within the system that created the problem, tasked with a tidy resolution that avoids public scandal—a subtly cynical, yet fitting, angle for a paranoid, post-WWII-inspired thriller.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Engines of Investigation

Mystic Hospital operates on a sophisticated, layered loop that HOPA designers would later refine but rarely equal in complexity. Its systems can be deconstructed as follows:

1. The Core Exploration Loop: The player navigates a large, semi-non-linear map of the hospital grounds and surrounding areas (fountain courtyard, garage, morgue, chapel, hangar, graveyard, etc.). Progression is gated by inventory items and puzzle solutions, but often multiple paths are available. The Notebook (with “Story” and “Goals” tabs) is the primary narrative and objective tracker, a significant upgrade over the simple task lists common at the time.

2. Hidden Object Scene (HOS) Variants: The game masterfully employs three distinct HOS types, preventing monotony:

* Standard Word-List: The classic format, with lists of 18-24 items (starting with 12, adding more as you find items). Objects are often cleverly hidden or require transformations (e.g., using a hammer on a ship-in-a-bottle to get a toy ship).

* Interactive/Placement Searches: The player must find items and place them onto correct associated objects within the scene. The Big Fish walkthrough details this: “Match all the items in the list to their associated objects.” This actively engages the player with the environment, making them think about context.

* Silhouette/Transformation Searches: Some items are listed in red, indicating a required action (e.g., “use paintbrush on white cat to get black cat”). This integrates inventory use directly into the search, blurring the line between HOS and adventure gaming.

3. Puzzle & Minigame Diversity: This is where Mystic Hospital truly distinguishes itself. The walkthroughs are a testament to its puzzle density and variety:

* Logic & Pattern: The “Anomalous Cards” solitaire variant (requiring suit/number matching to reveal a code), the switch-light puzzles (like the detonator sequence requiring light patterns), and the wheel-turning puzzles (rotating steps to horizontal).

* Mechanical & Assembly: Pipe-connecting puzzles, lock-picking with tumblers (adjustable to key teeth), and the intricate Crystal Gun puzzle in Chapter 4, requiring a precise, non-overlapping arrangement.

* Musical & Memory: The chapel door lock (repeating a melody) and the organ puzzle (repeating progressively longer note sequences).

* Environmental & Alchemical: The recipe-based concoction in Chapter 4, where players must place items (ice, alcohol lamp, distilled water, salt, crystals) in the correct order on a tray, referencing out-of-order journal pages. This is a brilliant puzzle that requires cross-referencing environmental clues.

* Codebreaking: Multiple codes are derived from environmental clues (numbers on a photo, playing card sequences, a decoder chart from a projector) and used on keypads or teletype machines. The final elevator puzzle (lighting all bulbs via a branching choice network) is a particularly devious logic grid.

4. The Anomalous Activity Detector (AAD) & Nexus: These are not mere UI elements but core gameplay pillars. The AAD functions as a contextual hint system, highlighting active zones. Skipping puzzles (with a 30-minute penalty) or using hints in HOS is governed by a recharge timer (60 sec Casual, 120 sec Advanced), providing a balanced difficulty curve. The Nexus is the central progression device. Finding the five Nexus Tubes (one per chapter) is a constant sub-goal, and using them on the monster energy at the end of each chapter is the primary victory condition, tying the entire gameplay to the narrative goal of containment.

5. Inventory & Collectibles: Inventory management is streamlined but impactful. Items are clearly marked (cyan in walkthroughs). Two major optional collectibles exist: 20 Postcards (scattered in环境的角落, often requiring backtracking insight) and 6 Top Secret Files (which unlock cutscene replays). These encourage thorough exploration and reward completionism. The Collector’s Edition adds a Bonus Adventure, a separate 2+ hour chapter with its own intricate puzzles and HOS, effectively doubling the game’s value.

The system design philosophy is clear: every action should have a diegetic reason. Picking up a “horseshoe” isn’t just loot; it’s used later on a machine. The game respects the player’s time by ensuring inventory items are generally used in the vicinity where they are found or in logically connected areas, minimizing pointless hauling.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Eerie Beauty of a Dead Hospital

Visually, Mystic Hospital is a masterclass in atmospheric, low-tech rendering. The fixed, flip-screen perspective creates a diorama-like quality, each screen a carefully composed painting. The art direction, credited to Orneon’s internal team on MobyGames, leans into a Post-Impressionist realism with a muted, desaturated palette of grays, greens, and browns that perfectly evokes a decaying, rain-swept, post-war institution. The hospital interiors are a labyrinth of peeling wallpaper, broken furniture, and oppressive shadows, while the exterior areas—the overgrown fountain courtyard, the misty graveyard, the bleak hangar—feel authentic and lived-in. Character portraits for the monsters are impressively rendered, blending human pathos with monstrous features (Sylvani’s crackling electrical aura, Lycaon’s hunched, furred silhouette).

The sound design is the unsung hero. The background score is a minimalist, ambient tapestry of low drones, distant creaks, and sporadic, unsettling musical stings. The use of diegetic sound is exceptional: the drip of water in the morgue, the crackle of the Burning Man’s flames, the howl of the wind in the graveyard, the constant, low hum of the Nexus. These sounds provide crucial auditory clues—the click of a mechanism, the sizzle of energy—and maintain a constant state of low-grade tension. The PEGI 7 rating is telling; the horror is entirely atmospheric and psychological, relying on implication, sound, and shadow rather than graphic imagery. This is horror for the imagination, a choice that amplifies dread.

The world-building is environmental storytelling at its finest. The Top Secret Files, found in the game, are not just plot devices but artifacts: memos, schematics, and photographs that flesh out the backstory of Dagon’s project, the soldiers’ identities, and the catastrophic explosion. The hospital is a physical archive of this failure. Every room—the abandoned operating theater, the skeletal laboratory, the private quarters with personal effects—tells a micro-story of the tragedy. The transition from the grounded, clinical hospital to the more overtly supernatural chapel and hangar marks a narrative shift from scientific horror to paranysical reckoning, a brilliant pacing device.

Reception & Legacy: The Critically Loved, Historically Overlooked

At launch, Mystic Hospital existed in the shadow of giants like Mystery Case Files and Phantom of the Opera, but it garnered a devoted following within the casual hardcore. The absence of professional critic reviews on Metacritic is symptomatic of the era; HOPAs were rarely reviewed by mainstream outlets. However, its legacy is preserved in player sentiment. On Steam (where the Collector’s Edition was released in 2016), it holds a remarkable Player Score of 95/100 from 21 reviews, with 94% positive. Comments praise its “balanced mix,” “atmosphere,” and “long bonus game,” aligning perfectly with contemporary reviews like Gamezebo’s 90/100 assessment, which called it “far from just another HOG cliché” and highlighted its “wonderful blend” and “fantastic locations.”

Its influence is subtle but present. The Agency of Anomalies series, continued by Orneon with Cinderstone Orphanage (2012), The Last Performance (2012), and Mind Invasion (2013), refined the formula but never quite matched the tight, self-contained narrative of Mystic Hospital. The series’ emphasis on “neutralizing” paranormal entities via investigation rather than combat can be seen as a precursor to later narrative-focused adventure games. Within the HOPA genre, its use of a persistent diegetic UI (Notebook, Top Secret Files), multi-stage environmental puzzles, and optional but rewarding collectibles became more common in subsequent high-end casual titles.

Tragically, Orneon Games shuttered around 2014, making Mystic Hospital and its series a final testament to their design philosophy. It represents the end of an era before the casual market shifted towards mobile hyper-casual and free-to-play models, and before the indie adventure revival (à la Primordia or The Dagger of Amon Ra) began to reclaim the genre’s narrative prestige. Mystic Hospital stands as a peak of what the “Big Fish Games” model could produce: a substantial, story-rich, mechanically diverse package that felt generous and complete.

Conclusion: A Canonical Case for a Lost Classic

The Agency of Anomalies: Mystic Hospital is a masterwork of its form. It transcends the “casual” label not through sheer production value but through relentless, intelligent design. Every system—from the AAD’s gentle guidance to the Nexus’s narrative integration, from the three-tiered HOS design to the puzzle ecosystem that feels like a series of locks tailored to unique keys—serves a dual purpose: gameplay challenge and narrative reinforcement. The setting is a character, the story is a cohesive tragedy, and the gameplay loop is satisfyingly dense without being punitive.

Its historical significance lies in its demonstration of the HOPA genre’s capacity for depth. In an era often remembered for click-fests, Mystic Hospital demanded memory, logical deduction, and environmental awareness. It respected the player’s intelligence, trusting them to piece together clues from a notebook, a photograph, and a scattered postcard.

To label it merely a “good hidden object game” is a profound understatement. It is a great adventure game that happens to use hidden objects as one of its primary verbs. It is a meticulously built artifact of a specific time—the early 2010s casual boom—that captures the ambition of a small studio at the height of its powers. For the historian, it is an essential study in genre evolution, diegetic UI, and atmospheric world-building on a budget. For the player, it remains a haunting, challenging, and deeply satisfying investigation that proves even the most overlooked corners of gaming history can hold treasures.

Final Verdict: 9.5/10 — A foundational text in the HOPA canon, The Agency of Anomalies: Mystic Hospital is a game of exceptional craft, narrative cohesion, and enduring atmospheric power. Its obscurity is a disservice to gaming history; its rediscovery is long overdue.