- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Developer: Jouni Utriainen

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Puzzle elements

- Average Score: 79/100

Description

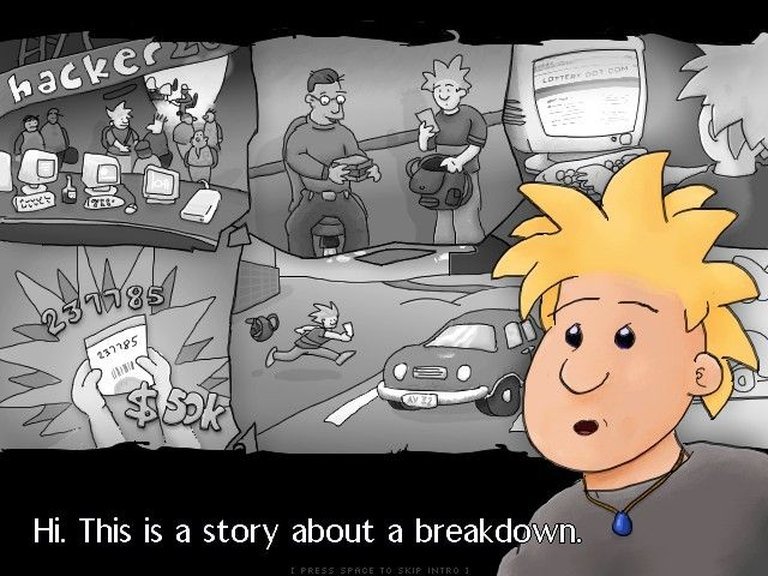

The Breakdown is a short, freeware point-and-click adventure game styled after classic LucasArts titles, featuring humorous cartoon graphics and puzzle-solving gameplay. Players control a young computer hacker who discovers a winning lottery ticket in his backpack while at a convention in another town, but with only five hours to claim the prize at the lottery office, his car breaks down, leading to a series of logical puzzles and trials to get back on the road in time.

Gameplay Videos

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

squakenet.com : It’s not something to crave, and if I hadn’t told you about it, you’d have never known it even existed!

The Breakdown: Review

Introduction

Imagine the thrill of unearthing a forgotten gem from the early 2000s gaming scene—a compact, freeware adventure that channels the whimsical spirit of LucasArts classics like Monkey Island or Day of the Tentacle, yet emerges from the unassuming hands of a solo developer. The Breakdown, released in 2003, is that elusive artifact: a point-and-click adventure that captures the essence of puzzle-solving hijinks amid a ticking clock, all while poking fun at itself and its inspirations. As a game historian, I’ve pored over archives, from MobyGames entries to long-lost download mirrors, to revive this obscure title for modern scrutiny. Though its brevity and freeware status have consigned it to the fringes of gaming memory, The Breakdown stands as a testament to indie creativity in an era when AAA adventures were waning. My thesis is simple: while not a flawless masterpiece, this “snack-sized” escapade exemplifies the enduring appeal of clever, self-aware design, offering a delightful snapshot of fan-driven homage that punches above its weight in humor and execution.

Development History & Context

The Breakdown emerged from the fertile ground of early 2000s indie development, a time when the adventure genre was experiencing a twilight phase. The golden era of LucasArts and Sierra had faded, with major studios shifting toward action-heavy narratives or graphical adventures like The Longest Journey (1999) that prioritized cinematic storytelling over pure puzzle logic. Freeware and shareware scenes, however, thrived on the internet’s nascent distribution power, allowing hobbyists to distribute games without publisher backing. Enter Jouni Utriainen, a Finnish developer whose passion project became The Breakdown. Utriainen wore nearly every hat—writing the script, crafting graphics and animations, composing sounds, and handling coding—making this a true solo endeavor, likely born from academic or personal experimentation, as hinted by credits thanking supervisors like Marko Siitonen and reviewers like Mika Lammi for a “term paper of the project.”

The game’s engine, AGAST (Adventure Game Authoring System), was pivotal to its creation. Developed by Russell Bailey and Todd Zankich, AGAST was a free toolset designed for aspiring creators to build point-and-click adventures without deep programming knowledge. Credits profusely thank the duo—”without your amazing Adventure Game Authoring System this game would never have been made”—and the broader AGAST community forums for support. This reliance on open-source-like tools underscores the era’s technological constraints: Windows PCs in 2003 ran on modest hardware (think Pentium III processors and 128MB RAM), limiting scope to lightweight, 2D graphics. Utriainen’s vision was explicitly nostalgic, aiming to revive LucasArts-style humor in a bite-sized format, complete with references to classics. The gaming landscape at release was dominated by MMORPGs like World of Warcraft (in beta) and shooters like Half-Life 2 (pre-release hype), but indie adventures found niches on sites like GameHippo.com, where free downloads fostered cult followings. Released as public domain freeware, The Breakdown bypassed commercial pressures, allowing unfiltered creativity, though its obscurity today stems from this very lack of marketing—it’s now a treasure hunt via archives like Internet Archive.

Beta testing involved a small circle of friends (Ville Salervo, Aleksi Munter—who also scored the music—Mikko Ekholm, and others), reflecting grassroots development. Special thanks to Heidi Härkönen add a personal touch, humanizing the process. In context, The Breakdown fits into a wave of freeware revivals, like Enigma (2003), that kept the adventure flame alive amid industry shifts toward realism and multiplayer.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, The Breakdown weaves a taut, time-sensitive tale of misfortune and ingenuity, framed through a lens of irreverent humor that pays homage to its LucasArts forebears. The protagonist is a young computer hacker—depicted with pointy hair reminiscent of Dilbert or classic adventure everymen—attending a convention in a distant town. Rifling through his backpack, he discovers an overlooked lottery ticket: a winner worth claiming, but with a brutal deadline of just five hours to reach the lottery office back home. Elation turns to despair as his car sputters and dies en route, stranding him in a quirky rural nowhere. The narrative unfolds as a series of escalating trials to repair the vehicle, blending everyday absurdities with puzzle-driven escapades.

The plot is linear yet episodic, structured around key locations like the breakdown site, a nearby farm, a mechanic’s shop, and perhaps a diner or roadside oddity—though sources describe it as “disparate sets” without a tightly woven overarching arc, suggesting an unfinished or experimental feel. Characters are archetypal yet endearing: the hacker himself is a wry narrator, voiced through text and animations that convey frustration and cleverness. Supporting cast includes eccentric locals—a gruff mechanic, a chatty farmer, or a know-it-all passerby—whose dialogues brim with witty banter. References abound: the classic taunt “I am rubber, you are glue” (echoing Monkey Island‘s insult sword-fighting) signals self-aware nods to genre tropes, while puzzles often riff on adventure clichés like inventory misuse or illogical item combinations.

Thematically, The Breakdown explores serendipity versus chaos, with the lottery win symbolizing fleeting fortune upended by mechanical betrayal. Humor is its lifeblood—intelligent, Ariadne’s-thread-like wit that builds to a “strong point” in the finale, per reviews—poking fun at hacker stereotypes (e.g., tech-savvy solutions to analog problems) and the absurdity of timed quests. Underlying it is a meta-commentary on adventure games themselves: the protagonist’s trials mirror player frustration with pixel-hunting and obtuse puzzles, turning potential irritation into comedy. Dialogue is sharp and concise, avoiding verbosity to suit the short runtime (1-2 days per Polish review), yet it delivers punchy lines that elevate the narrative beyond mere setup. No deep lore or moral ambiguity here; instead, it’s a lighthearted ode to persistence, where themes of luck and improvisation resonate through cartoonish exaggeration. While some critiques note a lack of cohesion, this brevity amplifies its charm, distilling the genre’s essence without bloat.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

As a point-and-click adventure, The Breakdown adheres faithfully to LucasArts’ verb-less paradigm—click to examine, interact, or use items—emphasizing exploration and logical deduction over trial-and-error frustration. The core loop is elegantly simple: survey scenes for hotspots, collect inventory items (e.g., tools from the car trunk or odd roadside finds), and apply them to puzzles blocking progress toward car repair. Mouse-only input keeps it accessible, with a save/load system allowing pauses in the five-hour narrative clock (which, mercifully, isn’t real-time, avoiding Majesty-style panic).

Puzzles form the backbone, described universally as “logical” and non-obtuse, rewarding observation over obscurity. Examples might include jury-rigging a part with hacker gadgets, bartering with locals, or solving environmental riddles like distracting animals or decoding a simple mechanism— all tied to the repair quest. Innovation shines in its economy: no red herrings or dead ends, per reviews, making it beginner-friendly yet satisfying for veterans. Character progression is minimal; the hacker gains no stats or branches, focusing instead on inventory management, which stays uncluttered to prevent overwhelm in the short playtime.

The UI is clean and era-appropriate: a third-person perspective with smooth panning across detailed scenes, an inventory bar at the bottom, and intuitive right-click examines. Flaws emerge here—some reviews cite bugs (e.g., pathing glitches in animations or minor crashes), acknowledged by Utriainen on the original site, which could disrupt flow. No voice acting means text-heavy dialogue, but animations add expressiveness. Overall, systems feel polished for freeware: the AGAST engine enables fluid interactions without the clunkiness of older SCUMM ports. It’s not revolutionary—lacking modern features like hint systems—but its tightness makes it a “snack-sized” delight, completable in hours without fatigue.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The Breakdown‘s world is a compact, cartoonish microcosm of Americana absurdity: sun-baked roadsides, cluttered garages, and quirky small-town vignettes that evoke Full Throttle‘s dusty vibes but with a lighter, hand-drawn flair. Settings are sparse yet evocative—five or so locations suffice for the tale—building immersion through meticulous detail rather than sprawl. The atmosphere is one of frantic levity; the ticking clock instills urgency without dread, amplified by humorous environmental storytelling (e.g., discarded items hinting at locals’ eccentricities).

Art direction is a standout: Utriainen’s graphics boast high resolution for 2003 freeware, with detailed, hand-animated sprites that pop in vibrant colors. The cartoon style—exaggerated expressions, bouncy walks—mirrors LucasArts’ charm, from the hacker’s windswept hair to scenery like rusted car parts or windswept fields. Animations are “perfect and detailed,” per Czech reviews, enhancing expressiveness without taxing hardware. This visual cohesion crafts a whimsical tone, where every pixel serves the humor, contributing to an experience that’s approachable yet nostalgic.

Sound design complements seamlessly: original score by Aleksi Munter features jaunty, upbeat tracks that underscore comedy, with an standout intro evoking Western showdowns or Desperado-esque flair. In-game music loops subtly, enhancing puzzles without overpowering, while sound effects (Utriainen’s work) add punch—creaks, honks, and quips ground the cartoon world. The finale’s sequence is lauded as cinematic, blending audio-visuals for a memorable close. Collectively, these elements forge an intimate, atmospheric bubble: not vast like Myst, but potent in evoking joy and ingenuity, making the short journey feel expansive.

Reception & Legacy

Upon 2003 release, The Breakdown garnered solid critical acclaim within freeware circles, earning a 79% average from six reviews on MobyGames (aggregated to a 7.5/10 user score, though player reviews are absent). Eastern European outlets dominated praise: Freegame.cz awarded 98/100 for its near-perfection as freeware, hailing logical puzzles despite lacking Czech localization. GameHippo.com’s 90/100 called it “one of the best freeware adventures ever,” lauding brevity as a strength. FreeHry.cz (85%) appreciated wit and atmosphere but dinged shortness and bugs, while PlnéHry.cz/iDNES.cz (80%) and Hrej! (80%) extolled graphics, music, and humor, deeming it a “must-download.” A outlier, VictoryGames.pl’s 40% (2/5) critiqued length and glitches but recommended it to classic adventure fans.

Commercially, as freeware, it had no sales metrics—downloads via the developer’s site and mirrors like Internet Archive sufficed—but inclusion in Retro Gamer Issue 6 (2004) lent retro credibility. Post-launch, reputation evolved into obscurity; a 2023-ish Squakenet review labels it a “very obscure” student project, hard to source, possibly unfinished, with disjointed scenes. Yet, this cult status endures among preservationists.

Influence is niche but notable: as an AGAST showcase, it inspired other freeware adventures like Between Heaven and Hell (credited overlaps). Utriainen’s 20+ other credits suggest it honed skills for broader indie work. In the industry, it exemplifies early indie revival of point-and-clicks, prefiguring Kickstarter-era homages like Thimbleweed Park (2017), and underscores freeware’s role in genre survival amid 2000s console dominance. Its legacy? A preserved relic, whispering that great ideas need no budget.

Conclusion

In dissecting The Breakdown, we uncover a freeware jewel that distills adventure gaming’s soul—humor, logic, and homage—into a concise, engaging package. Jouni Utriainen’s multifaceted vision, powered by AGAST, overcomes 2003’s constraints to deliver sharp narrative beats, intuitive mechanics, and vivid art-sound synergy, despite minor bugs and brevity. Reception affirmed its quality, and though obscurity clouds its legacy, it endures as a beacon for indie creators, influencing micro-adventures in a post-LucasArts world.

Final verdict: The Breakdown merits a solid 8/10 and a firm place in video game history as an underdog triumph. Seek it on archives; its charm rewards the hunt, proving that even breakdowns can lead to breakthroughs.