- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Encore Software

- Developer: Creature Labs Ltd.

- Genre: Compilation

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Setting: a, n

Description

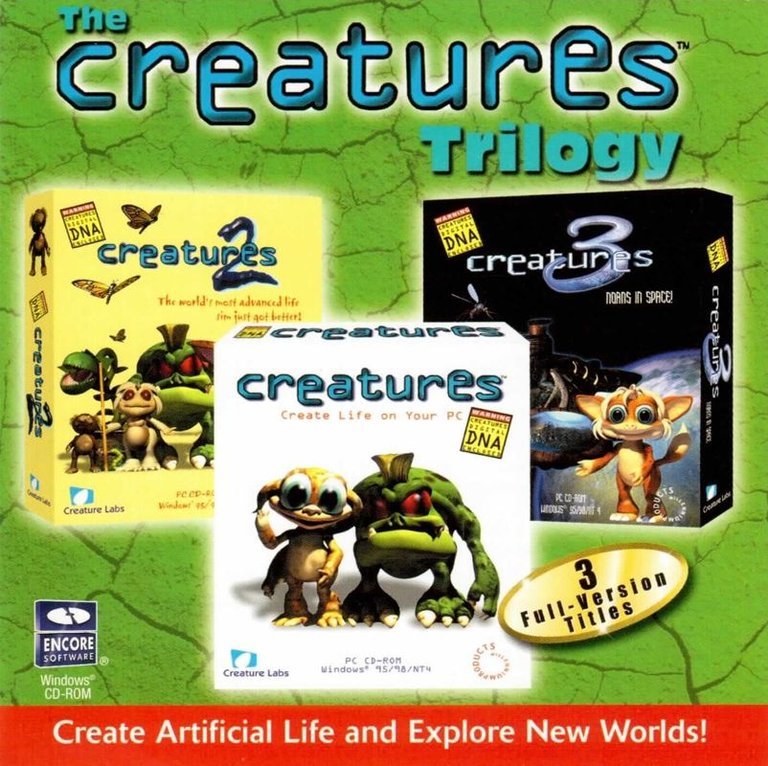

The Creatures Trilogy is a comprehensive compilation of the groundbreaking artificial life simulation series. It includes the complete base games Creatures (1996), Creatures 2 (1998), and Creatures 3 (1999), along with the official add-ons Life Kit #1 for both Creatures and Creatures 2. Players are tasked with nurturing and guiding generations of evolving alien creatures called Norns, managing their genetics, teaching them skills, and protecting them from environmental threats across diverse digital ecosystems.

Guides & Walkthroughs

The Creatures Trilogy: A Monument to Artificial Life and Neglected Legacy

Introduction

In the vast pantheon of video game history, few series have dared to ask as much of the player or reached for such a profound, almost philosophical goal as the Creatures trilogy. This compilation—encompassing Creatures (1996), Creatures 2 (1998), Creatures 3 (1999), and their respective Life Kit add-ons—represents not just a collection of games, but a singular, ambitious vision of artificial life that remains largely unparalleled. More than a simple pet simulator, the Creatures series was a bold experiment in digital biology, a complex ecosystem contained within your PC, and a narrative about playing god with consequences. This review posits that while commercially niche and technologically constrained, The Creatures Trilogy is a landmark achievement in emergent gameplay and artificial intelligence whose ambition and depth continue to cast a long shadow, making it a subject of fascination for historians and a cherished cult classic for those who ventured into its demanding, beautiful worlds.

Development History & Context

The Studio and The Vision

The trilogy was the brainchild of Creature Labs Ltd. (formerly Cyberlife Technology), a UK-based studio led by Steve Grand, a visionary who had previously worked on SimCity and Populous. Grand’s vision was not to create a game in the traditional sense, but to engineer a true “digital universe” populated with sentient beings. This was not mere marketing hyperbole; the team included actual biologists and AI researchers. Their goal was to create the Norns—the game’s central creatures—not as pre-scripted automata but as entities with a simulated biochemistry, a neural network for a brain, and genuine capacity for learning. This was a monumental task in the mid-1990s, a period where most games were still grappling with 3D acceleration and simple sprite-based logic.

Technological Constraints and Ambition

The technological landscape of the era is crucial to understanding the trilogy’s achievement. Creatures (1996) was released in a world dominated by the first Tomb Raider and Super Mario 64. While those games pushed polygonal limits, Creatures pushed computational ones. Its innovation was under the hood: the COB (Creature Object Brain) language for scripting objects, and more importantly, the Digital DNA (D-DNA) system and the neural net architecture called the “brain lobe.” Each Norn was a unique combination of hundreds of genes governing everything from metabolism and appetite to personality and learning capacity. This was processing-intensive AI, running on consumer-grade Pentium processors. The subsequent sequels were attempts to expand this universe: Creatures 2 moved the setting to the lush, pre-rendered Albia, while Creatures 3 took a leap into a futuristic space station, the Shee Ark, introducing a fully 3D environment for the creatures to explore. The included Life Kits were essential expansions, adding new agents, objects, and genetic strains to combat the inevitable “gene rot” that occurred in closed populations.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The narrative of the Creatures trilogy is not delivered through cutscenes or exposition, but through environmental storytelling and player-driven discovery. The overarching lore paints a picture of a fallen, highly advanced civilization known as the Shee. Having abandoned their homeworld of Albia, they left behind their creations: the innocent, inquisitive Norns; the destructive, instinct-driven Grendels; and the helpful, robotic Ettins.

The player assumes the role of a “hand” (a remnant of Shee technology), essentially becoming a caretaker or god-like figure for this abandoned ecosystem. The core narrative is the player’s own: the struggle to nurture a thriving population of Norns, protect them from Grendels, understand their complex needs, and guide them toward intelligence and self-sufficiency. It is a narrative of creation, responsibility, and often, tragedy. The death of a Norn you have named and cared for from infancy is a genuinely emotional event, a direct consequence of your actions—or inaction.

Thematically, the games are profoundly rich. They explore:

* Nature vs. Nurture: Can a Norn born with “bad” genes be saved through patient teaching and care?

* The Ethics of Creation: What responsibility does a creator have for its creation? The Shee abandoned theirs; will you?

* Ecosystem Management: The world is a delicate balance. Introducing a new plant or animal can have unforeseen consequences on the entire food chain.

* The Meaning of Life and Intelligence: The games quietly ask what it means to be alive and sentient within a digital space. Watching a Norn learn to communicate its needs and even use tools to solve problems is a powerful experience that blurs the line between programmed response and genuine learning.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

To call The Creatures Trilogy a “game” is almost a misnomer; it is a biological simulation with game-like elements. The core loop is one of observation, experimentation, and caretaking.

- The Norn Life Cycle: Gameplay revolves around the complete life cycle of a Norn: from egg, to infant, to adolescent, to adult, and eventually, death. Each stage requires different care. Infants must be taught basic vocabulary (“push,” “eat,” “sleep”) through a rewarding click-and-reward system that genuinely feels like teaching a child.

- The Biochemistry Engine: This is the heart of the experience. Each Norn has a real-time readout of its internal state: glucose, glycogen, fat, water, lactate, and more. Poison, fatigue, and sickness are not status effects but natural outcomes of this internal chemistry. Administering medicine is a precise act of balancing chemicals.

- The Genetics System: This is the trilogy’s most revolutionary feature. Norns inherit genes from their parents that dictate everything from their lifespan and fertility to their susceptibility to disease and their curiosity. Players can use a complex tool to analyze and even splice genes, engaging in a form of digital eugenics to breed stronger, smarter generations. This system provided near-infinite replayability.

- The World as a System: Every element of the environment is interactive and has purpose. Plants grow and can be harvested, machines can be repaired or operated, and food can be cooked. The world is a puzzle to be understood so it can be managed for the benefit of your creatures.

- Flaws and Frustrations: The complexity is also its greatest barrier. The learning curve is vertiginous. The games provided minimal hand-holding, leaving players to fail—often catastrophically. The AI, while groundbreaking, could be buggy, leading to creatures getting stuck or behaving erratically. The reliance on the Life Kits to fix core issues felt necessary but also highlighted the fragility of the simulation.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The trilogy presents a fascinating evolution in its aesthetic.

- Creatures (1996): The original game has a stark, almost eerie beauty. Its 16-bit color palette renders Albia as a melancholic, metallic landscape of rusted ships and biological-looking computers, perfectly selling the idea of a world abandoned by its masters. The sound design is minimalistic, filled with ambient hums, creature chatter, and the haunting, beautiful soundtrack that became iconic.

- Creatures 2 (1998): This entry shifted to a lush, pre-rendered backdrop reminiscent of Myst. Albia is now a vibrant, green world with flowing water and dense jungles. It feels more alive and less post-apocalyptic, though the underlying melancholy remains. The audio expands with more diverse ambient sounds and creature vocalizations.

- Creatures 3 (1999): The leap to the Shee Ark space station was a drastic and bold change. The art direction embraced a clean, futuristic, and highly complex 3D environment. The multi-leveled rooms and connecting travel tubes created a truly immersive ecosystem to manage. The sound design became more technological, with the hum of machinery replacing the sounds of nature.

Across all three games, the art serves the core theme: you are a ghost in the machine, observing a fragile world. The sound of a Norn calling your name (“Hand!”) is a simple but incredibly effective piece of audio design that forges a powerful emotional connection.

Reception & Legacy

Upon their individual releases, the Creatures games were critical darlings praised for their staggering innovation, ambition, and unique appeal. They garnered a dedicated cult following and significant media attention for their advanced AI. Commercially, they were niche products, their complexity limiting their mass-market appeal.

The release of The Creatures Trilogy compilation in 2000 by Encore Software was a final, comprehensive package for this niche audience. It served as the definitive collection for newcomers and veterans alike, bundling the core evolutionary steps of the series along with the crucial Life Kit patches.

The legacy of The Creatures Trilogy is profound yet subtle. It stands as a high-water mark for artificial life simulations—a genre that few have attempted to tackle with such seriousness since. Its direct DNA can be seen in games like Black & White (which also featured a creature-training element) and Spore, though neither achieved the same level of underlying simulation. More recently, the explosion of the “cozy game” genre, with titles like Niche and countless pet sims, owes a debt to Creatures‘ pioneering blend of caretaking and emergent storytelling. It is frequently cited in academic circles discussing AI and ethics in games. However, its true legacy is its passionate modding community, the “Albia” that still exists today, where fans continue to create new breeds, objects, and worlds, keeping the intricate digital biology of these classic games alive decades later.

Conclusion

The Creatures Trilogy is not a game for everyone. It is a demanding, often opaque, and sometimes brutally unforgiving experience. It requires patience, curiosity, and a willingness to embrace failure as a learning tool. To judge it by standard gameplay metrics is to miss the point entirely. This compilation is a museum piece of ambitious game design, a time capsule from an era when developers were willing to risk everything on a complex, unique vision.

It is a flawed masterpiece. Its technological constraints are evident, its interfaces often cumbersome, and its learning curve is a wall. Yet, for those who scale that wall, the reward is an experience unlike any other in gaming: the profound joy of watching a digital being you taught to speak solve a puzzle on its own, the quiet sadness of a life cycle concluded, and the awe of tending to a truly living, breathing digital world. For its unparalleled ambition, its groundbreaking technology, and its enduring emotional resonance, The Creatures Trilogy secures its place as one of the most unique, important, and fascinating artifacts in video game history.