- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Windows 16-bit, Windows

- Publisher: Houghton Mifflin Interactive Corporation

- Developer: Houghton Mifflin Interactive Corporation

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Conversation trees, Fetch quests, Inventory management, Point and select, Puzzle solving

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 90/100

Description

The Day the World Broke is an adventure game where the Earth’s natural balance is thrown into disarray. Deserts have flooded, rivers have dried up, and cows are flying. The player discovers that the world is managed by a giant machine deep in the planet’s core, run by World Works engineers. Their attempted tune-up has caused this chaos. The player must journey to the center to figure out what went wrong. There, they encounter strange Mechanimals—part animal, part machine. By helping four Mechanimals with their problems, the player can restore the planet to normal. The game, intended for children, features a first-person perspective, conversational gameplay, hand-painted environments, and some live-action sequences.

Gameplay Videos

The Day the World Broke Free Download

The Day the World Broke Mods

The Day the World Broke Reviews & Reception

gamesreviews2010.com : A classic game that still holds up today.

gamefaqs.gamespot.com (90/100): A GREAT game, but desperately needs a patch.

The Day the World Broke: Review

Introduction

There are few artifacts of 1990s educational software that capture the imagination with quite the same whimsical, surreal, and inventive spirit as The Day the World Broke. Released by Houghton Mifflin Interactive in 1997, this point-and-click adventure has, over the years, transcended its origins as a children’s title to become a cult classic. It is a game that dares to be strange, a digital storybook that posits the Earth is not a planet, but a colossal machine run by two perpetually overworked engineers in an underground control room. When their “Great Tune-up” goes awry, resulting in flooded deserts and flying cows, a child is summoned to the planet’s core to fix the mess. There, they discover a forgotten civilization of “Mechanimals”—bizarre, charming hybrids of animal and machine—who hold the fate of the world in their grasp. This review posits that The Day the World Broke is a flawed but fascinating piece of interactive storytelling, a testament to the boundless creativity of a bygone era in game development. Its legacy lies not in technical perfection or commercial dominance, but in its unique, unforgettable world and the sheer audacity of its core concept, securing it a peculiar and cherished place in video game history.

Development History & Context

To understand The Day the World Broke, one must first appreciate the unique environment in which it was created. The title hails from Houghton Mifflin Interactive, a division of the storied American educational publishing house. This origin is paramount; the game was not designed to compete with the titans of mainstream gaming like Quake or Final Fantasy VII. Instead, its goal was to entertain while subtly educating, appealing to a “Kids to Adults” ESRB rating with a target audience likely around nine years of age. This edutainment context is key to understanding its design choices—a focus on narrative, dialogue, and creative problem-solving over action or complex mechanics.

The creative vision was spearheaded by acclaimed children’s book author and illustrator David Wiesner, who is credited not only for the story and visuals but also as a designer. Wiesner’s Caldecott-winning work, characterized by surreal, wordless narratives and intricate, painterly detail, is the unmistakable soul of the game. His influence permeates every frame, transforming what could have been a simple technical demo into a rich, story-driven experience.

Technologically, the game was built on the mTropolis engine, a multimedia authoring tool popular in the mid-to-late 1990s for creating interactive CD-ROM titles. mTropolis allowed for a highly integrated experience, blending hand-painted backgrounds, 3D computer-rendered characters, and live-action full-motion video (FMV). This technological constraint, however, also defined the game’s structure. The development credits list an impressive 94 people, a testament to the labor-intensive process of creating such a multimedia product in an era before modern game engines streamlined production. The game was developed for Windows 3.1 and 95, a landscape dominated by the rise of the CD-ROM as the primary medium for rich software. This was a time of experimentation, where games could be ambitious, sprawling, and filled with content that would be economically unfeasible today. The Day the World Broke is a perfect product of this specific moment—a time when a publisher could invest heavily in a niche, artistic title for children, confident that its uniqueness would find an audience.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The narrative of The Day the World Broke unfolds with a delightful absurdity that feels plucked from a beloved children’s book. The player character—a child whose gender is never specified, allowing for maximum identification—begins the game in their room, interrupted by a chaotic news bulletin announcing the planet’s catastrophic malfunction. This “tune-up” gone wrong has thrown the world into a state of surreal disarray, a premise that establishes the game’s central theme: the intersection of order and chaos, nature and technology.

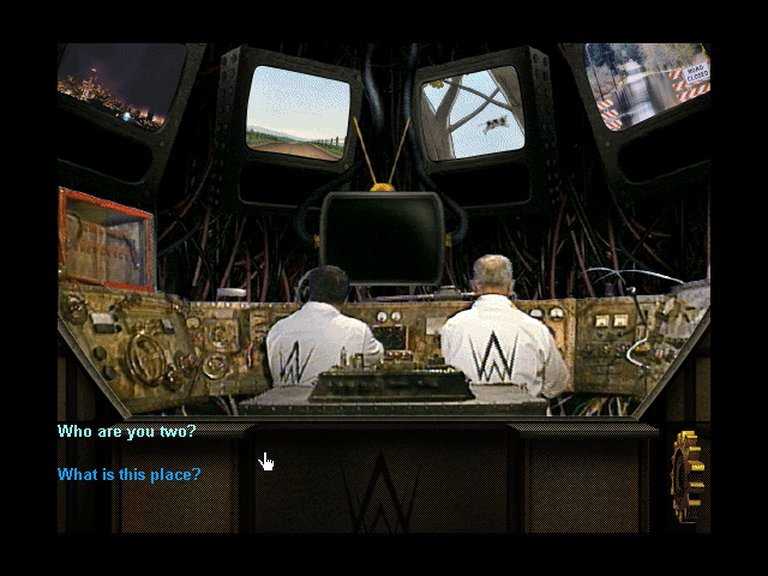

The core plot is a classic hero’s journey into the unknown. Guided by the bickering, overworked human engineers, Bud and Julius, the player descends into the Earth’s core via a magnetic pole described as “candy-striped.” This journey transports the protagonist to New Torque City, a vibrant, self-contained world sealed off from the surface for 65 million years. This “City in a Bottle” setting allows for a fascinating exploration of a society that has evolved in total isolation, developing its own culture, history, and mythology around the machinery it inhabits.

The narrative’s heart and soul are the Mechanimals, a gallery of brilliantly conceived characters. The game’s primary objective is not a traditional save-the-world quest, but a series of interconnected character-driven quests. The player must assist four key Mechanimals who are, quite literally, blocking the energy valves needed to restore planetary balance.

- Carbine, a lizard with a camera for a head, is the lead reporter for the New Torque Times. His quest is professional: his camera lens is broken, and he needs a replacement to do his job. His storyline delves into themes of truth, communication, and media.

- Phlange, a T-Rex-like creature fused with a tuba, is a historian and musician suffering from a creative block. Helping her involves finding inspiration, exploring the game’s theme of art and the creative process.

- Diode, a bird trapped in a brass sphere, is the story’s de facto antagonist. He is the only Mechanimal who immediately recognizes the player as a “human” and is obsessed with reaching the surface world, which he desires to rule. He serves as a counterpoint to the others’ more personal problems, representing grand ambition and a lust for power.

- The Derelict, a perpetually calm creature who mostly mutters “Really? Wow,” is perhaps the most intriguing. Through other characters, the player learns he is Ohm, a former apprentice who underwent a failed experiment in “mind uploading,” leaving his consciousness in a machine of “living glass” and his body as a vacant, amiable shell. This storyline is a surprisingly poignant exploration of identity, consciousness, and the consequences of unchecked scientific ambition.

The dialogue is fully voice-acted and presented through a conversational tree, where the player selects lines from a list. This system encourages experimentation and reveals different facets of the characters’ personalities. The writing is sharp, witty, and filled with puns (“world of torque,” “mechanimal”), perfectly matching the game’s comedic tone. The central theme, however, is more profound than its silly surface suggests: it’s about the interdependence of different systems and the idea that to fix a grand-scale problem, one must first attend to the small, personal ones. The world can only be saved by helping a reporter, a musician, a dreamer, and a madman, a lesson as applicable to society as it is to the game’s bizarre internal logic.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

As a first-person point-and-click adventure, The Day the World Broke‘s gameplay is rooted in exploration, conversation, and puzzle-solving. The core loop involves navigating the beautifully hand-painted environments of New Torque City, interacting with objects and characters to gather information and items. The interface is minimalist and intuitive, relying on a simple inventory system and a cursor that changes to indicate interactive hotspots.

The primary gameplay mechanic is dialogue. Progress is rarely achieved through traditional inventory-based puzzle-solving (though a simple inventory exists), but by talking to the game’s many inhabitants. Each conversation presents the player with a series of questions or statements to choose from. A successful playthrough requires the player to piece together information from multiple sources, navigate social cues, and fulfill the often-complex requests of the Mechanimals. This creates a “Chain of Deals” that is the game’s most significant puzzle element. For instance, helping Carbine get a new lens requires you to perform a series of tasks for other characters, each providing a piece of the solution.

This leads to the game’s most notorious feature: its lengthy fetch quest. The central task of assembling Diode’s anti-magnetic medallion involves traveling back and forth across the city, collecting specific components from various characters. While this structurally sound design methodically guides the player through every corner of the world, it can feel repetitive and tedious by today’s standards, especially for a younger audience.

However, the game’s gameplay is critically hampered by significant technical flaws. As noted in multiple sources, The Day the World Broke is infamous for its game-breaking bugs. The most severe is a freeze that occurs when characters are supposed to give the player an item. This glitch can render entire questlines impossible to complete, effectively soft-locking the player and forcing them to restart. A secondary issue affects the save game function, which is unintuitive and prone to failure. While some players report that completing tasks in a specific order can mitigate these issues, the bugs are a persistent and frustrating stain on an otherwise engaging experience. These problems are not merely minor annoyances; they are fundamental flaws that actively impede the player’s ability to finish the game, a serious flaw for any title, but one particularly damaging for a game aimed at children.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The Day the World Broke is a masterpiece of world-building and artistic design, and this is where its brilliance truly shines. The game’s aesthetic is a unique and successful fusion of several mediums. The environments are detailed, hand-painted watercolor scenes that look and feel like they were lifted directly from a David Wiesner book. The textures are soft, the colors are vibrant yet earthy, and the spaces are filled with charming, painterly details that reward close inspection. This artistic choice creates a dreamlike, storybook atmosphere that is both enchanting and slightly surreal.

In stark and brilliant contrast, the Mechanimals are fully rendered 3D characters. This hybrid approach was a technological showcase for its time and serves a narrative purpose. The flat, painted backgrounds feel like a fixed, established world—a stage set. The 3D Mechanimals, with their sometimes-clunky but full-of-character models, feel like living, breathing inhabitants of that stage. They pop from the environment, giving them a dynamic presence that the static backgrounds lack.

The human characters, Bud and Julius, appear in live-action FMV sequences. These segments are shot in a campy, B-movie style, with the actors performing amidst a set of blinking dials and flashing lights to simulate the World Works control room. The contrast between the FMV humans, the 3D creatures, and the 2D backgrounds is jarring at first but ultimately cements the game’s “collage” aesthetic, a reflection of its creation in a multimedia experimental age.

The sound design is another crucial component of the game’s identity. The Mechanimals are all fully voice-acted, and the quality of the performances is a highlight. The voice actor for Diode, in particular, is singled out for praise, delivering a performance that is both charming and menacing, capturing the character’s electronic speech impediment and manic ambition perfectly. The ambient sounds and the gentle, musical score work in harmony with the visuals to create a cohesive and immersive atmosphere, pulling the player deeper into the strange world at the Earth’s core.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its release in 1997, The Day the World Broke did not make significant waves in the mainstream gaming press. Its reception was, and remains, largely confined to niche circles, educational software reviews, and the memories of the children who played it. The lack of widespread critical analysis at the time is understandable; it was a small-budget, esoteric title from a non-game publisher, overshadowed by the graphical arms race of the era. However, its legacy has grown organically over the decades.

Today, its reputation has evolved from a simple children’s game to a cult classic. Online communities, abandonware sites, and private archives have kept the game alive. Its reputation is defined by two contradictory elements: immense creativity and profound technical failings. Players who successfully navigate its bugs are often left with a profound sense of affection, praising its unique art, charming characters, and imaginative world. The GameFAQs review by Wakerra is a perfect encapsulation of this sentiment: “A GREAT game, but desperately needs a patch.” This duality is the core of its legacy.

The game’s primary influence is not on gameplay systems or technology, but on narrative and aesthetic ambition. It stands as a testament to the potential of video games as a medium for pure, unadulterated storytelling and artistic expression, unconstrained by the commercial pressures that dominate the industry. It’s a reminder that a game’s identity can be built on a singular, powerful vision, rather than technical prowess. Its influence is seen in the modern indie scene’s embrace of weird, personal, and artist-driven games. Furthermore, the game serves as a valuable historical document, preserving a specific, fleeting moment in game development where educational and artistic goals could coexist in such a bold and experimental form. Its preservation on the Internet Archive and discussion on sites like Zomb’s Lair ensure that this unique artifact continues to be discovered and appreciated by new generations, solidifying its place as a beloved, if flawed, piece of video game history.

Conclusion

The Day the World Broke is a game of two halves. On one hand, it is a technical relic, a product of its time burdened by frustrating, game-breaking bugs that can prevent completion and a primitive interface that feels dated. These flaws are significant and cannot be ignored; they stand as a stark reminder of the technical limitations and developmental hurdles of the CD-ROM era. On the other hand, it is a work of pure, unbridled creativity, a singular vision brought to life with a charm and inventiveness that few games, then or now, can muster.

Its true genius lies in its world-building. The concept of the Earth as a machine and its core as a home for a forgotten civilization of “Mechanimals” is audacious and brilliant. David Wiesner’s artistic fingerprints are all over the game, transforming a standard adventure game framework into a living, breathing storybook. The memorable characters, from the ambitious Diode to the forgetful Derelict, are not just quest-givers but fully realized personalities with their own hopes and dreams. The game’s legacy is not as a commercial success or a technical benchmark, but as a beloved cult object. It is a testament to the idea that a game’s soul can outlive its glitches. For those willing to brave its technical quirks, The Day the World Broke offers a unique, charming, and unforgettable journey into the heart of a wonderfully broken world. It is, and will remain, a flawed masterpiece, a shining example of the strange and beautiful things that can happen when art, education, and technology collide in a whirlwind of whimsy.