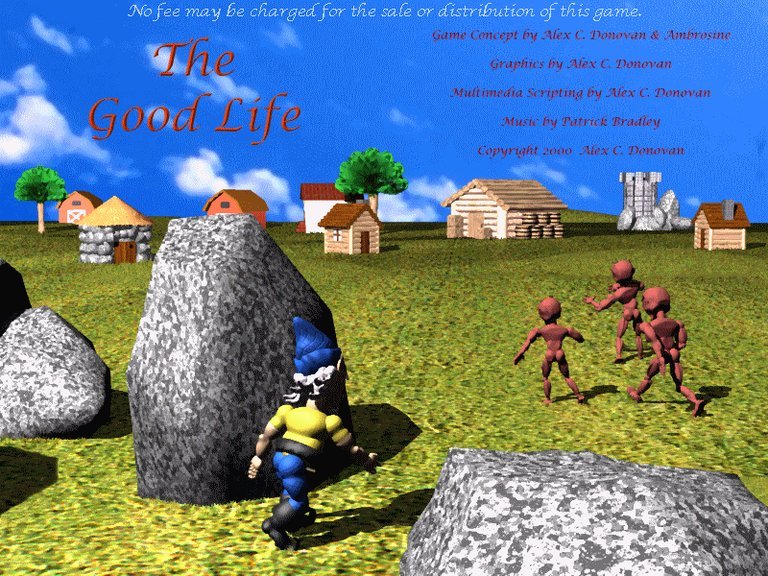

- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: Windows

- Genre: Action, Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: City building, construction simulation, Hero combat, Real-time strategy, Spell casting

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 66/100

Description

The Good Life is a multi-genre fantasy game where players must build a thriving village to defend against demons and fairies in a realm plagued by periodic attacks. The game unfolds in three parts: starting with a real-time strategy element to manage resources and construct buildings, followed by an action mini-game to win the aid of the Lord of the Fey, and culminating in a battlefield segment to destroy the demon portal.

Where to Buy The Good Life

PC

The Good Life Cracks & Fixes

The Good Life Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (62/100): While The Good Life still has some annoyances carried over from Deadly Premonition, it’s still a great time with some wacky characters.

pcgamer.com : Weird, good natured, and pretty funny with it, The Good Life stands apart, like most SWERY games.

opencritic.com (60/100): A surprisingly generous and deep life sim from the mind of Swery, but a frustratingly creaky one too.

rockpapershotgun.com : The Good Life is a shambolic RPG that barely hold together, wrapped in the trappings of a rural life simulator. It’s tonally stupid and structurally broken, but also surprisingly deep and occasionally self-aware.

The Good Life: Review

Introduction

In the pantheon of idiosyncratic auteurs shaping the landscape of interactive media, few loom as large as Hidetaka “SWERY” Suehiro, the mastermind behind cult classics like Deadly Premonition. His latest opus, The Good Life (2021), arrives not merely as a game but as a sprawling, multifaceted tapestry woven from the threads of rural English folklore, supernatural whimsy, and the mundane anxieties of modern life. Released to a wave of critical bewilderment and player fascination, this role-playing life simulator thrusts players into the rain-soaked streets of Rainy Woods—a village where inhabitants transform into cats and dogs under the full moon. As Naomi Hayward, a debt-ridden New York journalist, players embark on a journey that oscillates between cozy pastoral exploration and bizarre cosmic mystery. This review dissects The Good Life‘s ambitious fusion of mechanics, narrative ambition, and technical execution, arguing that while its structural flaws are undeniable, its unapologetic charm and thematic depth cement it as a flawed yet essential artifact in SWERY’s unique oeuvre. The game’s legacy lies not in polish, but in its daring to be gloriously, unrepentantly itself.

Development History & Context

The Good Life emerged from the fertile imagination of SWERY65 (Hidetaka Suehiro), the visionary creator of Deadly Premonition and D4, who co-directed the project with Yukio Futatsugi (Panzer Dragoon) and Takayuki Isobe. Funded through a successful Kickstarter campaign after an initial Fig attempt, the game materialized over a protracted development cycle delayed multiple times—a testament to its ambitious scope and the indie studio White Owls Inc.’s dedication to realizing SWERY’s eccentric vision. The 2021 release found the gaming landscape dominated by AAA extravaganzas and polished indies, positioning The Good Life as a counterpoint: a deliberately unpolished, genre-blending experiment. Technologically constrained by its modest budget and the unique challenges of simulating dual human-animal forms, the team leaned into a stylized aesthetic to compensate. The game’s genesis was deeply personal for SWERY, who sought to celebrate British culture while dissecting its idiosyncrasies through the lens of magical realism. This cultural reverence is evident in the meticulous recreation of the Lake District’s landscapes and the deep integration of folklore, from King Arthur legends to local superstitions. The project’s journey from crowdfunding to release was fraught with hurdles, including a publisher shift from The Irregular Corporation to Playism in 2021, yet these struggles ultimately shaped the game’s identity—a labor of love born from constraints and creative stubbornness.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, The Good Life is a narrative onion, peeling back layers of mystery with each act. The plot begins deceptively simply: Naomi Hayward, saddled with a £30 million debt, is exiled to Rainy Woods, England by her employer, Morning Bell News. Tasked with uncovering the town’s secrets to generate viral content, she stumbles upon the corpse of Elizabeth Dickens—a wheelchair-bound local—unraveling a ritual murder that defies logical explanation. This premise rapidly expands into a labyrinthine saga branching into three distinct routes (A, B, and C), each exploring different facets of Rainy Woods’ secrets: Arthurian lore, an extraterrestrial moss hive mind (“Simon”), and the town’s economic exploitation by corporate overlords. The narrative’s strength lies in its commitment to ambiguity and thematic juxtaposition. SWERY crafts a world where the mundane (debt repayment, photography quests) collides with the supernatural (shape-shifting, UFO sightings), creating a constant tension between the banal and the bizarre. Characters embody this dichotomy: the alcoholic vicar Benedict who refers to alcohol as “holy water,” the handyman Douglas McAvoy who never removes his knight’s armor, and the witch Pauline Atwood brewing potions in her woodland hut. Dialogue crackles with deadpan wit and non sequiturs, reflecting Naomi’s cynical perspective (“Goddamn hellhole…”) and the town’s collective eccentricity. Thematically, the game interrogates the commodification of authenticity in the digital age—Naomi’s photography for Flamingo (a social media stand-in) is both a lifeline and a hollow exercise—while also celebrating community resilience against predatory capitalism. The narrative’s refusal to provide easy answers mirrors the complex, unresolved mysteries of small-town life, culminating in an ending where Elizabeth’s resurrection and the preservation of Rainy Woods’ secrets come at the cost of Naomi’s journalistic credibility—a bittersweet victory for authenticity over exploitation.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The Good Life defies easy genre classification, blending RPG, life simulation, and exploration mechanics with a photography-driven economy. The core loop revolves around Naomi’s daily routines: managing hunger, sleep, and stamina while completing quests, photographing objects for social media “emokes,” and transforming into a cat or dog to access new areas. As a human, Naomi interacts with NPCs, crafts items (often requiring absurdly specific materials like 50 aluminum cans for a single backpack upgrade), and engages in dialogue. Her camera is pivotal—snapping “hotword”-triggered photos generates income, incentivizing environmental observation. The transformation mechanic, unlocked early, provides strategic depth: cats climb walls via glowing claw marks, dogs track scents (green puffs) and mark territory to unearth dig spots. Combat is minimal and clumsy—Naomi fends off badgers or deer by dodging and retaliating—but the game sidesteps traditional action in favor of resource management. Stamina depletes rapidly, requiring constant food intake, while status effects like colds or toothaches necessitate crafting potions from foraged ingredients. The quest structure, however, reveals systemic flaws. With only one active quest slot, players risk missing critical triggers, and backtracking across Rainy Woods’ expansive map becomes a slog. Crafting, a cornerstone of the life sim label, devolves into tedious “20 Bear Asses” grinding—fetching quail feathers or aluminum cans for marginal rewards. Yet the game peaks in its unscripted moments: sheep racing for quick cash, drinking contests with the vicar, or the disorienting joy of exploring the town as a cat. These emergent interactions highlight SWERY’s strength in creating systems that reward curiosity, even if execution is often inconsistent.

World-Building, Art & Sound

Rainy Woods itself is the game’s true protagonist—a meticulously crafted, uncanny valley of English pastoral life. Set in the Lake District, the village shrouds ancient secrets in its misty moors and crumbling ruins. From the Downer Hotel’s haunted interiors to the standing stones echoing with folklore, the world-building marries authenticity with surrealism. The full moon transformations are visualized with whimsy: residents don miniature hats and waistcofts in their animal forms, their human personalities subtly reflected (e.g., the vicar’s sheep retains a pious demeanor). Artistically, The Good Life adopts a stylized, low-poly aesthetic that prioritizes character expressiveness over realism. Character models feature exaggerated proportions and rubbery animations, enhancing the game’s cartoonish tone. Environments, though technically marred by texture pop-in and stiff lighting, evoke a cozy yet eerie atmosphere—the juxtaposition of quaint cottages against UFO landing sites or overgrown mines creates a dreamlike dissonance. Sound design amplifies this duality: the placid strumming of Henry Poe’s violin or the clinking of pub glasses contrasts with the unnerving silence of the snowy mines or the scuttling of dog-form Naomi through alleys. Composer Patrick Bradley’s score (echoing his work on the 2000 The Good Life) underscores moments of whimsy and dread, while ambient sounds—the bleat of sheep, the crackle of a fireplace—ground the supernatural in tangible reality. The result is a world that feels lived-in, where the mundane and the magical coexist in a delicate, fragile harmony.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its October 2021 release, The Good Life polarized critics. On Metacritic, it holds a “Mixed or Average” score of 62% for PC, with praise for its charm and narrative ambition tempered by criticism of its technical hiccups and repetitive gameplay. Reviewers like Tom Sykes (PC Gamer) lauded its “weird, good-natured” humor and “unforgettable characters,” while others like IGN Italia deemed it a “disorienting mix of elements” that “fails to fully flesh out social commentary.” Players on Steam echoed this divide, awarding it a “Mostly Positive” 77% score, with some praising the cozy exploration and others decrying the grind. Over time, the game’s reputation has shifted from divisive to cultishly adored, particularly among SWERY acolytes who cherish its sincerity over polish. Its legacy is twofold: it influenced indie developers to embrace genre-blending and narrative risk-taking, even as it became a case study in balancing ambition with execution. The game’s flawed systems—like the quest log or crafting—sparked debates on player agency and “fun” in life sims, while its unapologetic Britishness inspired renewed interest in folklore-inspired settings. Notably, its 2024 Collector’s Edition physical release on Switch and PS4 underscored its enduring appeal, cementing it as a niche but significant entry in the indie RPG canon.

Conclusion

The Good Life is a game of glorious contradictions: technically inelegant yet narratively profound, thematically rich yet mechanically frustrating. It stands as SWERY65’s most ambitious and personal statement—a love letter to British culture wrapped in a murder mystery, a critique of digital commodification layered with sheep-racing antics. While its structural flaws—repetitive quests, inconsistent systems, and technical jank—prevent it from reaching the heights of Deadly Premonition‘s cult status, they are inseparable from its charm. In an industry chasing cinematic perfection, The Good Life dares to be messy, human, and unapologetically weird. Its true achievement lies not in seamless gameplay but in fostering a connection to Rainy Woods—a place where the line between the magical and the mundane dissolves, and where, for all its frustrations, the “good life” is found in the journey itself. For historians of game design, it represents a vital artifact of indie experimentation and authorial vision; for players, it remains a flawed, unforgettable pilgrimage into the heart of SWERY’s boundless imagination. In the end, The Good Life is not just a game—it’s an experience, flawed and fleeting, yet undeniably worth living.