- Release Year: 2021

- Platforms: Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 4, Windows Apps, Windows, Xbox Cloud Gaming, Xbox One, Xbox Series

- Publisher: Active Gaming Media Co., Ltd.

- Developer: Grounding Inc., White Owls Inc.

- Genre: Role-playing, Simulation

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Life simulation, RPG elements, Social simulation

- Setting: Europe

- Average Score: 61/100

Description

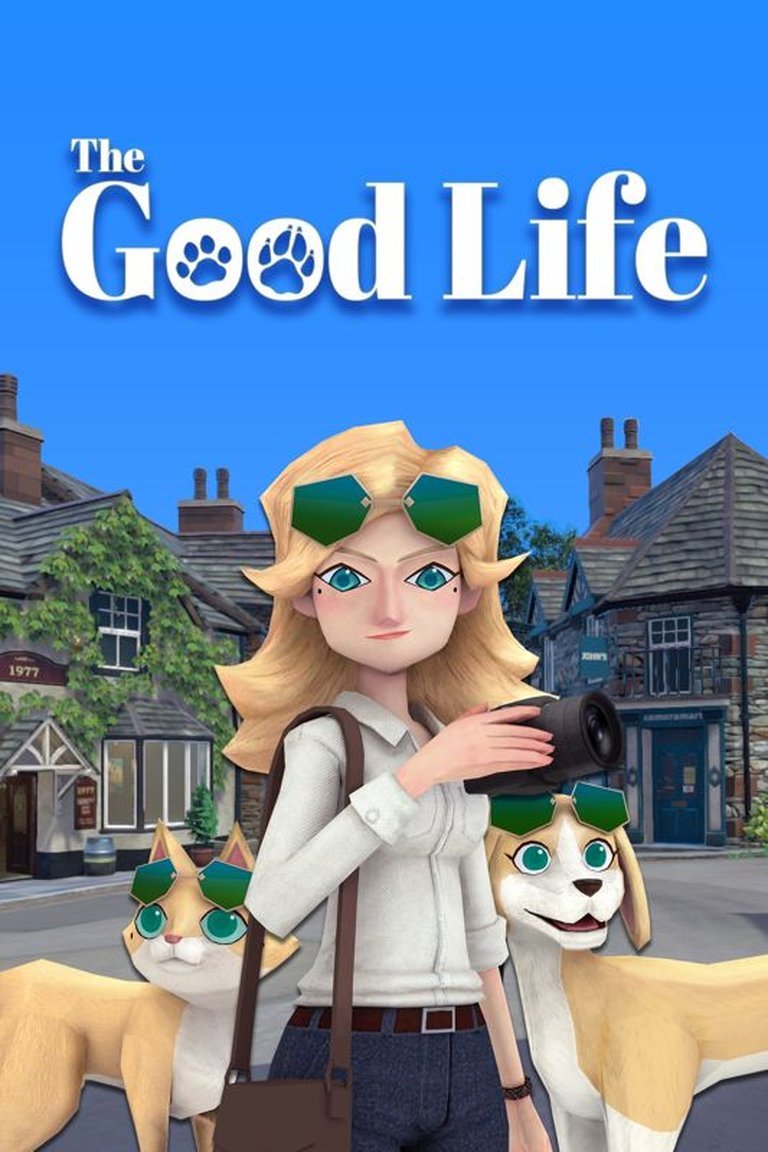

The Good Life is a role-playing simulation game set in a European town, blending life and social simulation with RPG elements. Players take on the role of a journalist investigating a detective mystery, interacting with locals and exploring the environment to uncover hidden secrets while experiencing daily life in the quaint setting.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy The Good Life

PC

The Good Life Free Download

The Good Life Mods

The Good Life Guides & Walkthroughs

The Good Life Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (62/100): It’s not a masterpiece but it’s certainly worth the trip.

pcgamer.com : Weird, good natured, and pretty funny with it, The Good Life stands apart, like most SWERY games.

arstechnica.com : Though technically rough and uneven, The Good Life is memorable and anything but predictable.

opencritic.com (60/100): A surprisingly generous and deep life sim from the mind of Swery, but a frustratingly creaky one too.

The Good Life: A Messy, Magnanimous Ode to the British Countryside

Introduction: The Cult of Swery and the Debt-Ridden Dream

In the sprawling, homogenous landscape of modern gaming, where open-world checklists and live-service models dominate, Hidetaka “Swery65” Suehiro has carved a niche defined by delightful, disorienting messiness. His 2021 title, The Good Life, is not merely a game but a concentrated dose of his singular authorial voice—a bizarre, heartfelt, and often frustrating cocktail of rural life simulation, supernatural mystery, and trenchant social satire. Following the cult phenomenon of Deadly Premonition, Swery’s debut with his studio White Owls Inc. promised a “debt repayment RPG” set in the rain-slicked, secret-saturated English village of Rainy Woods. What arrived was an experience that perfectly encapsulates the Swery ethos: technically janky, narratively audacious, and utterly unforgettable. This review argues that The Good Life is a flawed masterpiece of indie game design—a game whose structural and technical shortcomings are inextricable from its profound charm and thematic ambition. It is a game about the search for authenticity in a commodified world, delivered via a mechanism that is itself deeply flawed, making its ultimate message resonate all the more poignantly.

Development History & Context: A Kickstarter-Fueled Odyssey

The genesis of The Good Life is as idiosyncratic as the game itself. Following his departure from Access Games after D4: Dark Dreams Don’t Die, Swery founded White Owls Inc. in Osaka in 2016. His vision was explicitly personal: to create a game celebrating British culture while dissecting its peculiarities, a direct counterpoint to his previousAmerican-set horrors. He was joined by Yukio Futatsugi, the legendary creator of the Panzer Dragoon series via his studio Grounding Inc., whose expertise in RPG systems provided a crucial counterbalance to Swery’s narrative focus.

The project’s funding journey was tumultuous. An initial Fig campaign in late 2017 failed to meet its $1.5 million goal, raising only ~$680,000. Undeterred, the team launched a Kickstarter in March 2018 with a more modest ¥68 million (approx. $623k) target. This succeeded dramatically, ultimately securing ¥81,030,744 from 12,613 backers. This crowdfunding success was not just financial validation but a blueprint for a niche, passion-project development model, directly shaping the game’s scope and community expectations.

Development, led by a core team of fewer than 25 at White Owls with Grounding’s support, was protracted and iterative. Built in Unity with production help from UNTIES, the game utilized a stylized, “adult picture book” aesthetic to compensate for budget constraints. The ambitious dual-human/animal transformation system, expansive open world, and multi-route narrative were legitimate technical hurdles. delays piled up: from an initial 2019 target to spring 2020, then to summer 2021, and finally to autumn 2021. A significant mid-stream change saw publisher The Irregular Corporation mutually part ways with White Owls, with Playism taking over publishing duties in June 2021 to see the project over the finish line. This convoluted path—failed crowdfunding, multiple delays, a publisher swap—forged the game’s identity. The Good Life is a product of stubborn vision persisting through adversity, and that struggle is visibly etched into its code and design. Its release on October 15, 2021, across PC, Switch, PS4, and Xbox One (plus Game Pass day-one) was a triumph of perseverance, albeit one arriving with notable technical baggage.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Curse of Authenticity

Swery’s narrative is a deliberate, chaotic tapestry woven from seemingly disparate threads: the mundane grind of debt, the supernatural whimsy of lycanthropy (or rather, “cat-/dog-morphism”), and a murder mystery that spirals into cosmic horror and Arthurian legend. The plot is structured around three distinct narrative routes (A, B, C), each triggered by specific side quests and exploring different supernatural explanations for the town’s curse and the murder of Elizabeth Dickens.

The protagonist, Naomi Hayward, is a brilliantly sour counterpoint to the saccharine setting. A debt-ridden New York photojournalist sold into indentured servitude to the predatory Morning Bell news conglomerate, she arrives in Rainy Woods with a chip on her shoulder and a camera in hand. Her mission—to uncover the town’s secrets for viral content—immediately collides with the town’s core phenomenon: every full moon, residents transform into miniature, costumed cats and dogs. Naomi soon gains this ability herself via a potion from the local “witch,” Pauline Atwood.

The narrative’s genius lies in its relentless tonal whiplash and thematic depth. On one level, it’s a cozy cottagecore sim; on another, a sharp satire of digital capitalism. Naomi’s primary income comes from uploading photos to “Flamingo,” a social media stand-in, where “emokes” (likes) translate to pennies. This mechanic is a direct critique of the gig economy and the commodification of experience—Naomi must literally aestheticize the “happiest town in the world” to survive, echoing contemporary influencer culture. The game constantly asks: what is the value of an authentic experience when it must be filtered through a lens for monetization?

This is juxtaposed against the town’s own curated authenticity. Rainy Woods is a facade, a “happiest town” branding that hides debts, curses, and murder. The residents are a gallery of Swery’s signature eccentrics: the knight-armor-clad handyman Douglas McAvoy, the mushroom-obsessed cafe owner Bruno, the violin-playing Henry Poe who “communicates through musical echolocation,” and the vicar who refers to alcohol as “holy water.” Their dialogue is a masterclass in deadpan snark and non-sequiturs, with Naomi’s grumbled “Goddamn hellhole” becoming a apt leitmotif.

The three narrative routes delve into increasingly outlandish lore:

* Route A focuses on the town’s dark history and a ritual tied to the “Bloodwoldes” family line.

* Route B introduces a puppeteer parasite: sentient, glowing moss from another planet (the “Simon” hive mind) that has possessed local man David O’Reilly, directly linking it to the murder scene.

* Route C pulls in Arthurian legend, with the murder weapon revealed as the real Curtana (Sword of Mercy) and a character claiming descent from King Arthur.

Crucially, the game subverts the classic mystery reveal. The Un-Reveal trope is central: none of the supernatural leads ever identify Elizabeth’s actual killer. The resolution comes when Elizabeth resurrects, revealing the murder was ultimately meaningless within the town’s hidden cosmic framework. The curse’s origin is never explicitly explained. This refusal to provide tidy answers is a thematic statement—the “good life” is found not in solving mysteries but in accepting the inexplicable, communal burdens, and quiet joys. The bittersweet ending sees Naomi’s journalistic credibility destroyed (she declares all her reports fake to protect the town’s secrets) but her debt paid and her place in Rainy Woods secured—a victory of personal connection over professional exploitation.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Framework of Friction

The Good Life is a hybrid “debt repayment RPG” that clumsily but ambitiously glues together life sim, photography game, and exploratory RPG. The core loop is deceptively simple: earn £30 million by any means to escape indenture.

-

Photography & Economy: Naomi’s camera is her primary tool. She receives assignments from The Morning Bell and townsfolk, and must photograph subjects matching daily “Hotwords” trending on Flamingo (e.g., “sheep,” “UFO,” “mushroom”). This incentivizes obsessive environmental scanning. Income is meager, creating a constant, grinding pressure. The photography mechanic is satisfying in the moment (framing a shot, seeing “Emokes” roll in) but becomes a repetitive chore, a direct simulation of the soul-crushing content grind it satirizes.

-

Transformation System: The signature mechanic. Naomi can shift between Human (dialogue, crafting), Cat (climbing marked surfaces, pouncing on small game for hides), and Dog (tracking green scent trails, digging, swimming). The system is conceptually brilliant, enabling creative exploration and puzzle-solving. However, its execution is dated. Stamina drains rapidly in animal forms, forcing constant management. The controls are stiff, and the utility often feels prescribed—you know you need to be a cat to scale a specific church wall. It provides joy in traversal (riding a sheep at high speed as a dog is a highlight) but rarely evolves beyond its initial gimmick.

-

Life Sim & Resource Management: Naomi must manage hunger, fatigue, hygiene (charisma affects vendor prices), and sickness (colds, toothaches). These are cured via potions from Pauline, requiring foraged ingredients. She can garden (plants grow in one day, no watering), cook, and craft. Here, the game succumbs to classic “20 Bear Asses”fetch quests. Upgrading a camera strap might require 50 aluminum cans; a new pair of shoes needs quail feathers and beaver pelts. These tasks feel like arbitrary padding, disrupting the narrative momentum and exposing the thinness of the life sim layer.

-

Quest Structure: The game’s greatest flaw. Only one main quest can be active at a time. The expansive map of Rainy Woods and its surrounding biomes (forests, mines, beaches, snowy peaks) means constant, tedious backtracking. Side quests from the rich cast are often simple deliveries or fetch tasks, and the game lampoons this itself (“Another fetch quest?!”), but doesn’t subvert it. The pacing is glacial, with major plot moments frequently separated by hours of mundane chore-running.

-

Combat & Puzzles: Combat is minimal and clumsy—dodging and light counter-attacks against badgers or deer. Puzzles are primarily environmental (use dog scent to track, cat climb to reach) or simple minigames (a maze-platformer during a trial). The game is at its best when these systems organically intersect with exploration, not when they are forced into standalone, repetitive tasks.

In summary, the gameplay is a bundle of promising systems competing for attention, with the grinding economy and restrictive quest log actively working against the relaxing, exploratory vibe the world evokes. It’s a game that often feels like a chore to play, which is ironically thematically resonant but mechanically frustrating.

World-Building, Art & Sound: The Charms of Rainy Woods

If the gameplay is the game’s Achilles’ heel, the world of Rainy Woods is its saving grace—a character-rich, atmospheric sandbox that justifies the player’s sufferance.

-

Setting & Atmosphere: Inspired by the English Lake District, Rainy Woods is a masterclass in curated quirk. The “happiest town” is a patchwork of quaint cottages, a haunted pub, a standing stone circle, a mine filled with Japanese cherry blossoms (an unexplained, Unusually Uninteresting Sight for the NPCs), and even a UFO landing site in the peat moss. The full-moon transformations are a nightly visual treat: townsfolk don tiny animal hats and waistcoats, their human personalities subtly reflected in their animal behavior (the vicar’s sheep still has a pious air). The juxtaposition of bucolic calm and lurking supernatural absurdity creates a persistent, dreamlike dissonance.

-

Visual Direction: The game employs a stylized, low-poly aesthetic with exaggerated, rubbery character animations. This prioritizes expressiveness and comedic timing over realism. While technically plagued by texture pop-in, stiff lighting, and a general lack of polish (a common criticism across all platforms), the art style has a consistent, storybook-like identity. The environments, despite technical hiccups, evoke a cozy yet eerie mood. The color palette is muted and rainy, punctuated by the vibrant glow of Flamingo notifications or the lurid green of dog-scent trails.

-

Sound Design & Music: The audio landscape is a crucial pillar of the atmosphere. Composer Patrick Bradley’s score (a veteran from the 2000 The Good Life) delivers gentle, whimsical melodies for town exploration and tense, ambient tracks for mysterious locales. The sound design is packed with personality: the clink of pub glasses, the bleat of sheep, the scuttle of paws, the distinct pop of a camera shutter. Voice acting, fully dubbed in English (and Japanese), is a major highlight. The cast, led by Rebecca LaChance’s perfectly exasperated Naomi, delivers Swery’s eccentric dialogue with deadpan conviction, selling the town’s bizarre logic. The contrast between the peaceful soundtrack and the unsettling silence of the snowy mines or the UFO’s psychic hum is masterfully done.

The world’s construction is so dense with incidental detail and systemic behavior (NPCs have daily schedules) that its inherent charm frequently overpowers the mechanical frustrations. Exploring Rainy Woods, stumbling upon a sheep race or a drinking contest with the vicar, feels genuinely alive.

Reception & Legacy: The Cult of the Imperfect

Upon release, The Good Life received a “Mixed or Average” reception, scoring 62/100 on Metacritic for PC. The critical consensus was remarkably consistent in its dichotomy:

* Praised: The unique transformation mechanics, the strength and eccentricity of the writing/characters, the charming and atmospheric world, the thematic ambition, and the “Swery-ness” of the whole package.

* Criticized: Repetitive and tedious fetch quests, the restrictive single-active-quest system, poor performance (especially on Switch), dated UI/UX, inconsistent pacing, and shallow execution of promising systems.

Review excerpts perfectly capture this divide:

* MonsterVine (90%): “A peculiar and endearing game… the setting, characters, and various activities are as pleasing as they are immersive.”

* PC Gamer (79%): “Weird, good natured, and pretty funny with it, The Good Life stands apart, like most SWERY games.”

* Rock Paper Shotgun (Unscored): “A shambolic RPG that barely holds together, wrapped in the trappings of a rural life simulator. It’s tonally stupid and structurally broken, but also surprisingly deep and occasionally self-aware.”

* IGN Italia (58%): “A disorienting mix of elements and mechanics that just don’t work well together… ends up feeling more like a list of chores.”

Player reception was similarly polarized but leaned slightly more positive on Steam (“Mostly Positive,” 74% of 181 reviews) than on aggregators like Metacritic user scores (5.9/10). Players who connected with the tone celebrated the quirky characters and the joy of exploration, while others bemoaned the grind and control issues.

Its legacy is twofold:

-

The Auteur’s Calling Card: For better or worse, The Good Life is the purest expression of Swery’s creative vision to date. It lacks the horror edge of Deadly Premonition but doubles down on his love for absurdist humor, systemic world detail, and narrative audacity. It has cemented his status as a true auteur in gaming—a creator whose name is a genre标签 in itself, promising a specific, acquired taste. It is cited as a touchstone for “punk” or “anti-polish” game design, championed by fans of Suda51 or Onion Games.

-

A Case Study in Ambition vs. Execution: The game is frequently analyzed as an example of “jank” as an aesthetic. Its flaws are not incidental; they are part of its texture. The repetitive quests mirror Naomi’s own grind. The technical roughness mirrors the “unpolished” reality of Rainy Woods. This self-awareness—the game knowingly presents busywork—can be read as a subtle critique of game design itself, though many players simply find it frustrating. It sparked debates about player agency, the nature of “fun” in life sims, and whether niche indies should be held to the same standards as AAA titles.

The post-launch support was modest but noteworthy. A substantial V1.5 patch addressed numerous bugs and adjusted difficulty/rewards. More significantly, a DLC expansion, Behind the Secret of Rainy Woods (March 2023), added 12 new side quests, allowing players to spend more time with the cast and explore minor mysteries, directly responding to fan desire for more content. The announcement of a Collector’s Edition physical release by Limited Run Games in 2024 is the ultimate testament to its cult status—a game deemed valuable enough to preserve on shelf, warts and all.

Conclusion: An Essential, Flawed Artifact

The Good Life is not a game for everyone. Its deliberate pacing, archaic quest design, and technical shortcomings will alienate players seeking a smooth, compelling power fantasy. But for those willing to surrender to its peculiar rhythm, it offers something rare: a game that feels deeply, unapologetically personal. It is a love letter to a specific idea of England, a critique of modern work and digital identity, and a celebration of the bizarre found in the mundane.

Its gameplay is a clumsy vehicle for its themes, and that very clumsiness becomes part of the statement. The grind of taking photos for likes mirrors Naomi’s existential grind. The frustration of backtracking mirrors the oppressive weight of debt and routine. The ultimate resolution—choosing community and hidden truths over fame and profit—lands more powerfully because the player has felt that grind.

Historically, The Good Life belongs in the canon alongside other cult “jank” classics like Deadly Premonition, Katamari Damacy, or Chulip. It represents a strand of indie development where authorial vision trides polished execution, where the game’s flaws are the fingerprint of its creator’s hand. It is a vital artifact of 2020s indie design—proof that a game can be both deeply flawed and deeply meaningful, that charm and atmosphere can compensate for mechanical poverty, and that sometimes, the most “good life” is found not in a seamless experience, but in a beautifully, messily lived one.

Final Verdict: A flawed, frustrating, and utterly indispensable experience. It is Swery’s most cohesive narrative vision and his most inconsistent gameplay offering. To play The Good Life is to visit a place that feels alive in its imperfections—a village where the supernatural is ordinary, the work is tedious, and the “good life” is a hard-won, quietly defiant state of mind. For historians of the medium, it is a crucial study in auteur theory and niche appeal. For players, it is a gamble that, for those who connect, pays off in unforgettable character moments and a lingering, philosophical warmth. Rainy Woods is real, and it is waiting for you. Just pack your patience—and maybe a good pair of walking shoes.