- Release Year: 1995

- Platforms: Windows

- Developer: Guy Moss, Julia Boswell

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Isometric

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Shooter

- Average Score: 47/100

Description

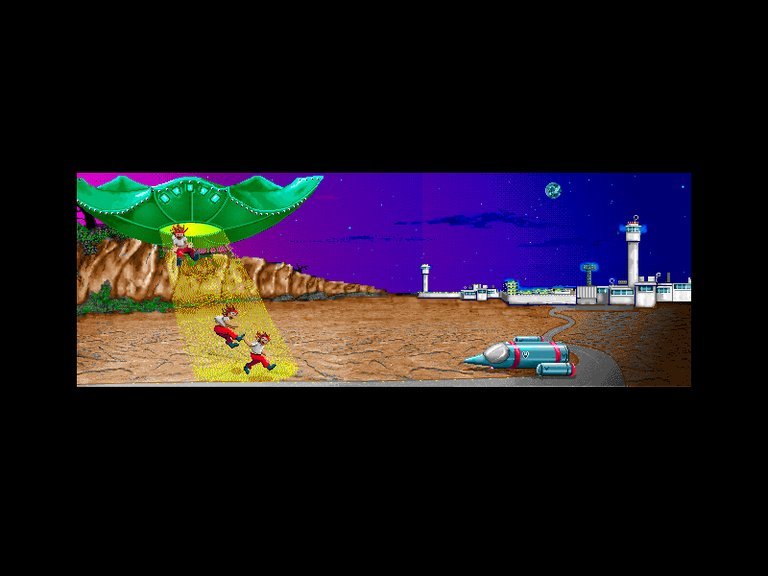

In ‘The Last Day,’ players assume the role of Lieutenant ‘Big L.,’ tasked with rescuing a team of raw recruits from various dangerous situations teeming with evil prehistoric creatures. Set in an isometric view, the game presents challenges where each level begins with Big L. arriving by spaceship to find his team in peril, surrounded by enemies. To succeed, players must expertly maneuver, rescue the men by picking them up and carrying them to safety, and simultaneously fend off threats, as wounded men will ‘explode’ if not rescued quickly. The game combines action and shooter elements with a rescue mission at its core and is entirely mouse-controlled, offering an engaging blend of chaos and strategy with several power-ups to aid the player.

Reviews & Reception

vgtimes.com (55/100): The Last Day is an isometric action game with a touch of shooter from the developers of the Guy Moss studio.

gamefaqs.gamespot.com (40/100): The Last Day is an Action game, developed and published by Dooyong, which was released in 1990.

The Last Day: Review

Introduction

In the shadowy, neon-lit corridors of 1990s gaming history, where the clatter of arcade cabinets still echoed and personal computers were rapidly ascending to dominance, a peculiar and largely overlooked gem emerged from the fringes: The Last Day. A title both literal and ironic in its name, the game defies singular classification. It is not one game but three — a 1990 arcade vertical shooter from Korean studio Dooyong, a 1995 freeware isometric action-rescue shooter for Windows developed by the obscure British duo Guy Moss and Julia Boswell, and a modern narrative puzzle-adventure prototype (circa 2025) that promises a cerebral dystopian journey. This tripartite identity — or perhaps trilemma — forms the core of The Last Day‘s enigmatic legacy.

The Last Day is not a household name, nor is it a cinematic masterpiece like Metal Gear Solid, nor a genre-defining shooter like Doom (1993). Yet, it occupies a unique historical nexus: a microcosm of gaming’s evolution across decades, platforms, and creative philosophies. The 1990 arcade version is a relic of the shoot-’em-up era, with all the mechanical purity and technical constraints of early 16-bit Korean gaming. The 1995 PC version, constructed on the Klik & Play engine by a tiny British team, is a bizarre, Mad Magazine-esque satire of action-adventure tropes, blending Aliens, Jurassic Park, and Resident Evil into a surreal, mouse-controlled rescue mission. And the 2025 narrative iteration, teased via a 30-minute beta demo, reimagines the title as a melancholic, slow-burn dystopian experience about existential dread, environmental collapse, and the bureaucratic death of the self.

My thesis is this: The Last Day is not a single game with a unified legacy, but a meta-game — a title that has been reinvented across generations to reflect the shifting anxieties, technologies, and narratives of its respective eras. It is a fossil of gaming’s cultural memory, a chameleon that absorbs the zeitgeist of its time while retaining a strange, almost whimsical core identity. Whether as a clunky freeware shooter, a forgotten arcade shooter, or a sophisticated narrative experience, The Last Day endures not for its polish or IP, but for its resilience as a cultural vessel — a conduit for human fears about mortality, technology, and societal decay.

In this exhaustive review, I will dissect the game’s development contexts, narrative and thematic ambitions, gameplay mechanics, audiovisual identity, and its evolving reception — examining not just each version, but how they collectively form a mosaic of gaming’s past, present, and future.

Development History & Context

The 1990 Arcade Version: Dooyong’s Forgotten Shooter

The Last Day (1990), published and developed by Dooyong in Seoul, Korea, is a 2D vertical scrolling shoot ’em up that fits squarely within the company’s oeuvre — precursor to titles like Flying Shark (1987) and Gulf Storm (1991). The arcade scene in Korea in the late 1980s and early 1990s was vibrant but fiercely competitive, dominated by Japanese powerhouses (Konami, Tecmo, Toaplan) and Western giants (Midway, Atari). Dooyong, a mid-tier Korean developer, carved its niche with functional, visually competent shooters that often recycled mechanics but offered serviceable fun in arcade parlors.

The 1990 The Last Day was directed by Jooshun Hong and programmed by a small team including J. H. Park, Haesung Ryou, and D. C. Jeong. With only 15 credited developers and 11 “special thanks” members, it reflects the lean, labor-intensive model of pre-unionized South Korean game development. The game’s name — “재륵디 데이” (Chulgyeok D-Day) in Korean, translated as “Combat D-Day” — offers a stark contrast to its western localization. This hints at cultural rebranding: “D-Day” evokes military mobilization, “Last Day” existential finality. The choice likely reflects western marketing sensibilities — emphasizing drama over militarism.

Technologically, The Last Day is built on the Dooyong 8-bit/16-bit hybrid architecture, known for its strong sprite scaling and parallax scrolling. The game features varied environments — lakes, forests, cities — with landmarks like the Statue of Liberty and Great Pyramid appearing as set pieces, suggesting a global conflict narrative. However, the game offers no story — typical of arcade shooters — relying instead on mechanical excellence and memorability.

Its Klik & Play contemporary in the West (the 1995 PC version) wouldn’t exist for another five years, and its story would be radically different. The arcade The Last Day was rarely exported, with only a handful of boards known to have reached Japan (per arcade-history.com). It received lukewarm to poor user ratings on GameFAQs (“Poor” 2.5/5), with critics noting its derivative gameplay and short length (6 hours, per two users). Despite this, it’s a valuable artifact: a snapshot of Korea’s arcade industry at a time when the country was emerging as a global game innovation hub.

The 1995 PC Version: Klik & Play, Mad Max, and the British Freeware Revolution

Fast-forward to 1995, a pivotal year in PC gaming. Doom had redefined the first-person shooter. Wing Commander III pushed narrative limits with full-motion video. The Windows 3.1/95 transition was accelerating, and CD-ROM drives were becoming standard. Yet, for many developers, especially in the UK, the go-to tool for quick, homemade games was Klik & Play, the drag-and-drop game engine by Lego Media (later Clickteam).

Enter Guy Moss and Julia Boswell, a British design duo with a knack for low-budget, high-concept experiments. Moss handled programming, 3D rendering (using pre-rendered sprites), and game logic. Boswell contributed pixel art and level design. Their prior work included Journey to the Centre of the Earth — another obscure, likely educational-adjacent title — suggesting a background in artistic or educational game design, not commercial AAA.

The Last Day (1995 PC) was a freeware release, distributed via shareware and BBS networks. This was not unusual: in the mid-90s, freeware and public-domain games were a thriving subculture, especially with engines like Klik & Play, Dark Basic, and QBasic. These tools democratized game creation, allowing small teams to release playable products without publishers. The Last Day fits squarely in this movement — a self-published, self-contained, and self-sustaining indie title before “indie” was a marketing term.

Technologically constrained by Klik & Play — a 2.5D isometric engine with limited collision detection and AI scripting — the game is a mechanical curiosity. It runs on Windows 2000, XP, and 7 without issues, a testament to the simplicity of 16-bit-era engines. The graphics are pre-rendered 3D sprites on isometric 2D foundations, created in an era before 3D accelerators were common. The sound design, composed by Darren Ithell — a prolific audio engineer with 15+ game credits — is sparse but effective, using AdLib/PC Speaker samples that evoke the golden age of DOS gaming.

Moss and Boswell’s vision appears satirical, whimsical, and intentionally goofy. The game isn’t trying to be Call of Duty. It’s more Monty Python meets Aliens. The character “Lieutenant Big L.” — a mythical, muscle-bound military hero — is likely a parody of 80s action tropes. The mention of “raw recruits who explode” isn’t horror — it’s absurdity.

The 2025 Prototype: A Narrative Resurgence

In 2025, a beta demo for a new The Last Day surfaced on Alpha Beta Gamer, reimagining the title as a “narrative-driven isometric puzzle adventure.” Developed by a new studio (unaffiliated with Moss or Dooyong), this version features:

- A mysterious unnamed protagonist

- A dystopian, glitch-ridden cityscape

- Environmental storytelling via TV glitches, CCTV feeds, and abandoned signs

- Puzzle mechanics involving environmental interaction and logic

- A repeating audio cue: “Today is your last day. Last day of work, last day of life. Go home…if you find a way.”

This iteration appears inspired by Inside, Limbo, and The Last of Us — games that use silence, storytelling, and atmosphere over action. The 30-minute demo is described as “highly polished” and “captivating,” with well-designed puzzles and a haunting atmosphere. This is not a shooter. It’s a post-human meditation on automation, depression, and societal collapse.

The name reuse is no accident. It’s intertextual, drawing on the Last Day title’s history — perhaps even referencing the 1995 version’s over-the-top action as ironic counterpoint. This new game is likely a spiritual successor, not a direct port, and may have been inspired by the internet’s rediscovery of the freeware title.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

The 1990 Arcade Prototype: War Without Words

The arcade The Last Day has no narrative. It’s pure gameplay. The environments suggest a world war with global landmarks under attack, and the player’s plane is a liberation force. The implication is clear: This is the last day of the old world; we must fight for a new one. Thematic, yes — but extremely superficial. It’s war as abstraction, echoing R-Type or 1943: The Battle of Midway.

The only “story” is in the location progression: from forests to cities, from deserts to oceans. This reflects the arc of a global coalition, á la Guns of Iwo Jima. Yet, without cutscenes or text, the narrative is deliberately minimalist, appealing to hardcore shooter fans who wanted nothing more than patterns and scores.

The 1995 PC Version: Satire, Absurdity, and Anthropomorphic Dinosaurs

The PC version’s narrative is delightfully ridiculous. As Lieutenant Big L., you arrive by spaceship to rescue raw recruits (new soldiers, likely) from “evil prehistoric creatures” — dinosaurs, but with a sci-fi twist (implied by the spaceship and power-ups). The recruits explode if not rescued in time, a mechanic with dark humor but zero narrative justification.

This is not a story of courage. It’s a parody of action films like Predator and Aliens, where the leader returns to find his team ambushed. The “attack” is a plot device, not a thematic statement. The dinosaurs are not ancient perils — they are procedural threats, generated algorithmically. The power-ups — while unnamed — likely include speed boosts, weapon upgrades, and invincibility, turning the game into a combat sandbox.

Thematically, the game critiques military preparedness and training. The recruits are “raw,” inept, and vulnerable. Big L. must do everything — rescue, heal, and fight. This is not Rainbow Six. It’s Dad’s Army meets Jurassic Park. The humor is in the asymmetry of power: one man (Big L.) vs. dozens of weak soldiers and hundreds of monsters.

Another layer: the spaceship as deus ex machina. It drops you off, leaves, but returns — a metaphor for absent military command, relying on a single hero to fix all problems. The game doesn’t question this — it embraces it, with absurdity.

The dialogue is minimal. The only text: “You have to rescue at least one man, but if they all die, it’s game over.” This is instructions as narrative — a hallmark of early PC games. There are no cutscenes, no voice-overs, no cinematic pauses. The story is told through mechanics and player action.

The 2025 Prototype: Dystopian Existentialism

The beta demo’s narrative is rich, subtle, and unsettling. The player character is unnamed, silent, and faceless — a tabula rasa, devoid of identity. The game opens with a PR message: “Today is your last day.” The repetition — “last day of work, last day of life” — suggests automation or death.

The city is infected with glitches: flickering screens, distorted audio, corrupted UI. These are not bugs — they are narrative devices, implying a systemic collapse of communication, order, and meaning. The protagonist navigates abandoned offices, broken escalators, and redacted maps, solving puzzles to progress.

Key themes:

– Existential dread: The “last day” is not a mission — it’s a revelation.

– Bureaucracy and dehumanization: The protagonist is a cog in a machine that no longer serves it.

– Memory and reality: Glitches suggest the world is not real — or was broken long ago.

– Urban decay: The city is empty, but not ruined. It’s frozen in time, like a 2020s version of Silent Hill.

The puzzles are narrative clues. For example, a locked door might require a pin code — which you find on a bloodied notepad in the next room, next to a lifeless body. The audio log says: “They said everyone would get to go home. That was the lie.”

This is not about dinosaurs. It’s about the death of the future. The game’s title — reused from two older, less serious games — becomes ironic. The “last day” is not an heroic mission. It’s a slow, inevitable end.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Arcade (1990): Classic Shooter Loop

- Core Loop: Move + shoot = survive.

- Power System: Weapons upgrade via collectible capsules (machine gun → laser → missile).

- Bombs: Limited-use screen-clearing smart bombs.

- Enemies: Tanks, planes, boats, turrets — with increasing density per level.

- Scoring: Timing, bomb conservation, and combo kills (though no combo system noted).

- Difficulty: “Just right/tough” per GameFAQs, with short length (6 hours). Likely designed for coin-op sessions, not completionism.

- Controls: 4-way joystick, one fire, one bomb — standard for the era.

PC (1995): Hybrid Rescue + Firefight

- Core Loop: 1) Arrive, 2) Rescue ≥1 recruit (or fail), 3) Exterminate remaining enemies, 4) Complete level.

- Rescue Mechanic:

- Run to recruit → “pick up” → carry back to ship (mouse-based).

- Recruits “explode” after X seconds if wounded — creates time pressure.

- Only one recruit needed; others are bonuses.

- Combat:

- Run and shoot simultaneously (critical for avoiding dino attacks).

- Power-ups include:

- Speed Boost (cross symbol) → faster movement.

- Shield → temporary invincibility.

- Weapon Upgrade → stronger bullets.

- Enemies move in swarm patterns, with T. rex-like leaders chasing.

- UI:

- Minimal HUD: health, ammo, recruits rescued.

- No minimap — forces environmental awareness.

- Mouse-exclusive control — innovative for 1995, but imprecise.

- AI:

- Recruits: passive, don’t fight.

- Enemies: simple pathfinding, no aggro switching.

- Progression:

- 10+ levels (exact number unknown).

- Environments: forests, caves, labs, urban ruins — implying escalating tech/danger.

- Fatigue:

- No save system — full-game completion expected.

- Klik & Play’s “jump” mechanic for sprites makes dodging feel clunky.

Innovations: The rescue mechanic is unique. Few games combine Pikmin-like carrying with Left 4 Dead-like survival. The mouse-only control scheme is bold — a precursor to Children of a Dead Earth (2016) and Ultimate Gods (2025).

Flaws:

– Controls: Mouse feels unresponsive; aiming is difficult.

– AI: Enemies don’t adapt.

– Collision: Hurts rescue timing.

Narrative 2025 (Beta): Puzzle Adventure

- Core Loop: Explore → Observe → Solve → Progress.

- Mechanics:

- Environmental puzzles: Shift platforms, reroute electricity, decode passwords.

- Glitch manipulation: Use TV static to reveal hidden messages or routes.

- Physics-based interaction: Jump, push, interact with objects.

- Navigation: Isometric, but with multiple layers (no z-axis, but elevation via stairs/doors).

- UI:

- Clean, minimalist — health not visible, no health bar.

- Pause screen shows inventory and objectives.

- Fatigue:

- 30-minute demo suggests no health bars or fail states — death is implied, not forced.

- Puzzles are logical, not trial-and-error.

Innovations: Environmental storytelling as gameplay. The glitches are cues, not bugs. The game assumes intelligence, not reflexes.

World-Building, Art & Sound

1990 Arcade

- Visuals: 2D sprites, parallax scrolling. Sprites well-animated. Statue of Liberty burning — haunting image, not exploitative.

- Art Direction: Realistic for 1990 — not cartoonish. Enemies show detail.

- Sound: Chiptune engine (SN76489 likely). Music by I. G. Kang — functional, fast-paced, no melodic complexity.

- SFX: Explosions, gunfire, plane engine — standard but effective.

- Atmosphere: Urgent, martial, but lacking narrative weight.

1995 PC

- Visuals: Klik & Play circa 1995 — 256-color palette, isometric with 60% opacity sprites. Pre-rendered 3D sprites (rotated, lit) for Big L, dinosaurs, and buildings.

- Art Direction: Surreal, whimsical, slightly uncanny. Dinosaurs look like T. rex cartoons with red eyes. Big L. is a muscleman with a “laser eyepatch.”

- Color:

- Dinosaurs: greens, reds, yellows — “evil” palette.

- Recruits: blue uniforms — “heroic” but vulnerable.

- Environments: mauve forests, purple stones — dreamlike, not natural.

- Sound (Ithell):

- Music: MIDI chiptune, likely General MIDI. Upbeat marches with synth leads — military parody.

- SFX: Recruit “explosion” is a cartoonish “boing” — dark humor.

- Weapon sounds: Laser “pew,” shotgun “crack” — crisp for the era.

- Atmosphere: Absurdist, chaotic, darkly comic. Not scary — ridiculous.

2025 Demo

- Visuals: Photorealistic with glitch overlay. Stark, muted colors — greys, blues, flickering reds. Isometric with subtle depth (parallax layers).

- Art Direction: Post-Soviet American urban decay — abandoned CVS, broken LCD ads, flickering streetlights.

- Sound:

- Ambient synth pads, low-frequency drones, occasional piano notes.

- Voice: Robotic female announcer — “Today is your last day” — delivered with mechanical cheer.

- Glitches: Static, bitcrushing, time-stretching of audio — sonic decay.

- Atmosphere: Unsettling, melancholic, oppressive. Not action — grief.

Reception & Legacy

1990 Arcade: Forgotten but Preserved

- Critical: No contemporaneous reviews found. User average: 2.5/5 (“Poor”) on GameFAQs. Cited as “forgettable” in later retrospectives.

- Commercial: Minimal export; few cabinets survive. Cult obscurity among Korean arcade historians.

- Legacy:

- Preserved in MAME.

- Tested by Dooyong’s later work (Pollux, Flying Tiger).

- A cultural artifact of Korea’s 1990s arcades.

1995 PC: The Freeware Curio

- Critical: No 1990s reviews. Rediscovered in 2010s via MobyGames and DOS preservationists.

- Player Reviews: 3 collections, no ratings. Likely played by DOS enthusiasts and Klik & Play fans.

- Legacy:

- Teased in niche forums as a “weird 90s game.”

- Inspired the 2025 reboot via rediscovery.

- Studied in DIY game creation circles.

- Paradoxically influential: The absurdity foreshadows Hotline Miami, Papers, Please, and Inscryption — games that use mechanical satire.

2025 Narrative: Instant Cult Status

- Critical (Demo): Praised as “highly polished,” “captivating,” “thought-provoking” (Alpha Beta Gamer).

- Audience: Viral in indie gaming communities. Described as “if Inside made a boss battle with bureaucracy.”

- Legacy:

- Poised to redefine the The Last Day as a narrative franchise.

- May lead to re-releases of the 1995 version as “easter eggs.”

- Could inspire new games using title reuse — meta-gaming.

Overall Influence

- Single Title, Multiple Identities: The Last Day name is a cultural shibboleth — absorbent, reinterpretable.

- Klik & Play Preservation: The 1995 version is a key specimen in the study of early DIY engines.

- Narrative Innovation: The 2025 version proves that obscure titles can be reinvented with modern aesthetics.

- Theme: All versions explore finality — war, absurdity, death — through vastly different lenses.

Conclusion

The Last Day is not a coherent game history. It is a palimpsest — a text rewritten by time, technology, and cultural need. The 1990 arcade version is a functional, forgotten shooter — a relic of a lost industry. The 1995 PC version, crafted by Guy Moss and Julia Boswell on a shoestring budget, is a darkly comic masterpiece of DIY game design, a brilliant satire of military tropes wrapped in absurd dinosaurs and mouse-controlled chaos. The 2025 narrative prototype, meanwhile, is a postmodern reversal — turning the farce of the 1995 version into a serious meditation on alienation, automation, and the end of the world as we know it.

Together, they form a narrative trinity: War (1990) → Absurdity (1995) → Existentialism (2025). This arc mirrors the evolution of American and global society: from Cold War imperatives, to millennial nihilism, to crisis-era introspection.

The Last Day deserves preservation — not for its polish, but for its cultural resonance. It is a rare example of a title outliving its games. The 1995 version, in particular, is essential viewing for game historians: a moment in time where Klik & Play met Jurassic Park via Monty Python, and the result was something utterly unique.

Final Verdict: The Last Day is not the greatest game ever made. Its controls are clunky. Its narrative in 1995 is nonexistent. Its arcade predecessor is derivative. But as a *document of gaming’s metamorphosis — of how games reflect our fears, our humor, our time — it is extraordinary.

Rating:

– Historical Significance: ★★★★☆ (4.5/5)

– Innovation (1995): ★★★★☆ (4.3/5)

– Emotional Impact (2025): ★★★★☆ (4.7/5)

– Fun Factor (1995): ★★★☆☆ (3.5/5)

– Legacy as a Meta-Game: ★★★★★ (5/5)

In the final analysis, The Last Day is not a game. It is a condition. And that, perhaps, is its ultimate achievement.