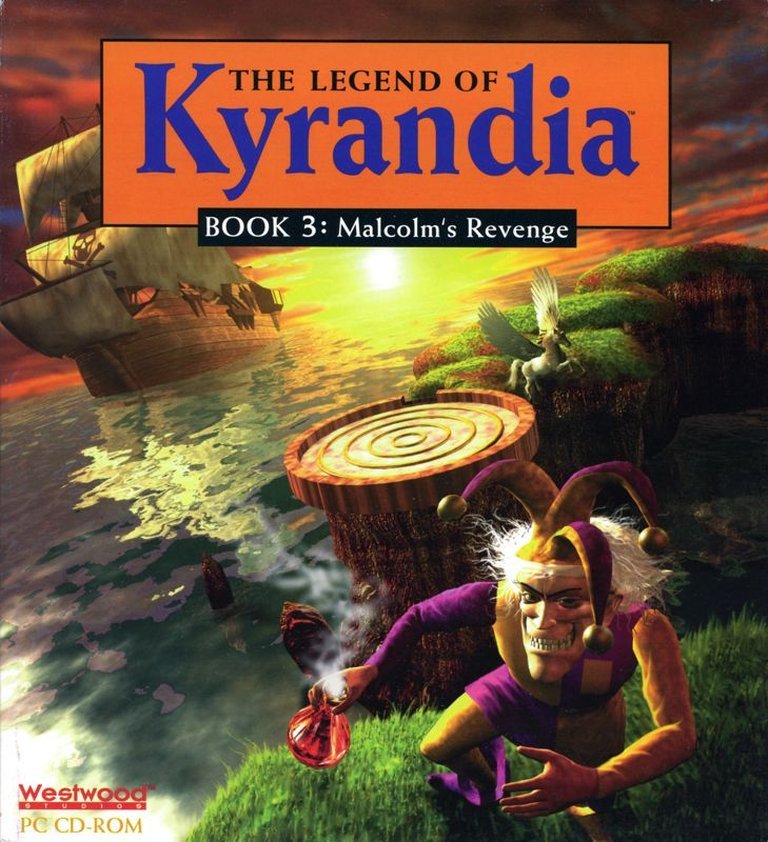

- Release Year: 1994

- Platforms: DOS, Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Electronic Arts, Inc., Virgin Interactive Entertainment, Inc.

- Developer: Westwood Studios, Inc.

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 3rd-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Graphic adventure, Multiple endings, Point and select, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 75/100

Description

The Legend of Kyrandia: Book 3 – Malcolm’s Revenge is the third installment in the Kyrandia adventure series, where players take on the role of Malcolm, the jester wrongly accused of turning Kyrandia’s royalty to stone. After being freed from his stony prison by a thunderbolt, Malcolm seeks to clear his name and reveal the truth, either through mischief or redemption. The game features classic point-and-click adventure mechanics with inventory-based puzzles, a ‘smart cursor’ for interactions, and a unique dialogue system that allows players to control Malcolm’s truthfulness and attitude. With multiple puzzle solutions, a humorous tone, and a fantasy setting, the game offers a fresh perspective on the series’ lore while maintaining its signature charm.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy The Legend of Kyrandia: Book 3 – Malcolm’s Revenge

PC

The Legend of Kyrandia: Book 3 – Malcolm’s Revenge Free Download

The Legend of Kyrandia: Book 3 – Malcolm’s Revenge Guides & Walkthroughs

The Legend of Kyrandia: Book 3 – Malcolm’s Revenge Reviews & Reception

mobygames.com (78/100): A worthy closing of the Kyrandia Saga!

myabandonware.com (88/100): Best Adventure genre game in 1994

gog.com (76/100): A perceived villain almost never gets to tell his or her side of the story.

bestoldgames.net (60/100): Players especially appreciated the unusual ability to regulate Malcolm’s behavior and a lot of options for solving tasks.

The Legend of Kyrandia: Book 3 – Malcolm’s Revenge: A Masterclass in Subversive Storytelling and Flawed Brilliance

Introduction: The Jester’s Gambit

In the pantheon of 1990s adventure games, few titles dare to invert the hero-villain paradigm as boldly as The Legend of Kyrandia: Book 3 – Malcolm’s Revenge. Released in 1994 by Westwood Studios, this final chapter in the Fables & Fiends trilogy is a study in narrative audacity, mechanical innovation, and the pitfalls of ambition. By casting Malcolm—the court jester and erstwhile antagonist of the first game—as the protagonist, Westwood didn’t just subvert expectations; they redefined the boundaries of player agency in a genre often criticized for its linear rigidity. Yet, for all its brilliance, Malcolm’s Revenge remains a polarizing artifact, a game whose strengths and flaws are inextricably linked, like the dual consciences of its troubled hero.

This review dissects Malcolm’s Revenge with the precision of a surgeon’s scalpel, examining its development context, narrative depth, gameplay systems, artistic achievements, and enduring legacy. It argues that while the game’s puzzles and structure may frustrate modern players, its bold storytelling and experimental mechanics cement its status as a cult classic—a flawed masterpiece that deserves reevaluation in the context of adventure game history.

Development History & Context: Westwood’s Swansong to Adventure

The Studio’s Evolution

Westwood Studios, founded in 1985, was already a veteran of the adventure genre by 1994, having released The Legend of Kyrandia (1992) and Hand of Fate (1993). However, the studio’s focus was shifting. The rise of real-time strategy games, exemplified by Dune II (1992), had captured the industry’s imagination, and Westwood’s internal resources were increasingly diverted to Command & Conquer (1995), a title that would redefine the RTS genre. Malcolm’s Revenge, then, was developed in the shadow of this transition, a final hurrah for a team that had honed its craft on fantasy narratives but was now eyeing the lucrative strategy market.

Technological Constraints and Innovations

The game’s development was shaped by the technological limitations of the era. Running on DOS, Malcolm’s Revenge utilized Westwood’s proprietary Vector Quantized Animation (VQA) format for its cutscenes, a compression technique that allowed for smoother video playback on the hardware of the time. The game’s pre-rendered 3D backgrounds, while ambitious, were a double-edged sword: they lent the game a cinematic quality but also dated it more quickly than the hand-drawn aesthetics of its predecessors.

The decision to include full voice acting and a CD-ROM release was similarly progressive. At a time when many adventure games still relied on text, Malcolm’s Revenge embraced multimedia storytelling, though the quality of the voice work varied. The game’s soundtrack, composed by Frank Klepacki (who would later score Command & Conquer), blended whimsical melodies with darker undertones, mirroring Malcolm’s dual nature.

The Gaming Landscape of 1994

The mid-1990s were a golden age for adventure games, dominated by LucasArts’ Monkey Island and Day of the Tentacle, which set the standard for humor, puzzle design, and player-friendly interfaces. Sierra On-Line, meanwhile, was pushing boundaries with King’s Quest VII and Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers, the latter of which demonstrated the potential of mature storytelling in the genre.

Malcolm’s Revenge entered this competitive landscape as an underdog. It lacked the polish of LucasArts’ offerings and the narrative depth of Sierra’s more ambitious titles. Yet, it carved out a niche for itself through its subversive premise and experimental mechanics, offering something neither of its rivals could: the chance to play as the villain.

The Vision Behind Malcolm

The game’s director and writer, Rick Gush, has spoken about the challenges of marketing Malcolm’s Revenge. In a 2002 interview with Adventure Gamers, Gush lamented that Westwood’s management was already fixated on Command & Conquer, leaving Malcolm’s Revenge under-promoted. Despite this, the game sold respectably, outselling its predecessors combined, thanks in part to bundling with earlier entries in the series.

Gush’s vision for Malcolm’s Revenge was clear: to deconstruct the hero’s journey by reframing it from the antagonist’s perspective. This was not merely a gimmick but a thematic exploration of morality, perception, and redemption. The game’s tagline—“A perceived villain almost never gets to tell his or her side of the story”—encapsulates its core philosophy.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Jester’s Redemption

Plot Summary: A Tale of Two Consciences

Malcolm’s Revenge opens with the eponymous jester, long imprisoned in stone for his alleged crimes—petrifying the royal family and murdering King William and Queen Catherine—being freed by a mysterious thunderbolt. From the outset, the game establishes Malcolm as a tragic figure, a man whose reputation has been sullied by circumstances beyond his control.

The narrative unfolds across several acts, each of which sees Malcolm navigating a different realm of Kyrandia, from the junkyard where he awakens to the surreal landscapes of the Isle of Cats and the Underworld. Along the way, he is guided (or misguided) by two manifestations of his conscience: Stewart, the benevolent but often ignored voice of reason, and Gunther, the malevolent, cigar-chomping imp who embodies Malcolm’s darker impulses.

The game’s climax reveals a twist that reframes the entire series: Malcolm was innocent of the royal murders. The true culprit was a cursed blade that killed anyone of royal blood who wielded it. This revelation, delivered by the ghost of King William, forces Brandon (the hero of the first game) and Kallak (the Mystic leader) to confront their own prejudices. Malcolm, far from being a villain, is revealed to be the king’s cousin, a fact that adds a layer of tragic irony to his persecution.

Character Analysis: Malcolm as the Antihero

Malcolm is one of the most compelling protagonists in adventure game history, a character whose complexity transcends the binary morality of traditional fantasy narratives. His design—gaunt, with a perpetual smirk and a jester’s motley—visually encapsulates his duality. He is neither purely good nor purely evil but a man caught between his desire for vengeance and his latent nobility.

The game’s Moodometer (a slider that adjusts Malcolm’s honesty and moral alignment) is more than a mechanical gimmick; it is a narrative device that allows players to explore different facets of his personality. Choosing to lie or tell the truth doesn’t just affect dialogue—it shapes how other characters perceive Malcolm, reinforcing the game’s central theme: perception is reality.

Supporting characters are equally memorable:

– Brandon, the erstwhile hero of the first game, is revealed to be a pompous, dim-witted figure, his reputation built on a lie.

– Kallak, the Mystic leader, is a hypocrite whose righteousness crumbles when confronted with the truth.

– The Pirate Captain, a grotesque figure who betrays Malcolm, embodies the game’s cynical view of power and loyalty.

Themes: Truth, Redemption, and the Subjectivity of Villainy

Malcolm’s Revenge is, at its core, a meditation on the nature of truth and the subjectivity of villainy. The game repeatedly asks: Who decides who the villain is? The answer, it suggests, lies in who controls the narrative. Malcolm’s journey is one of reclaiming his story, of proving that the jester—often dismissed as a fool—can be the most perceptive figure in the room.

The game also explores redemption through the lens of self-acceptance. Malcolm’s ultimate choice—whether to embrace Stewart, Gunther, or both—is a metaphor for integrating one’s flaws and virtues. The game’s ending, in which Malcolm is pardoned but left to grapple with the consequences of his actions, is bittersweet, avoiding the neat moral resolution of traditional fantasy.

Dialogue and Writing: Wit and Whimsy

The writing in Malcolm’s Revenge is sharp, often hilarious, and occasionally profound. Malcolm’s quips—delivered with a mix of sarcasm and world-weariness—are reminiscent of LucasArts’ best work, though with a darker edge. The game’s humor is not just comedic relief but a tool for undermining the gravity of its themes. For example, the laugh track, a sitcom-style audience reaction to Malcolm’s antics, is both a meta-commentary on the absurdity of his situation and a way to soften the game’s more melancholic moments.

However, the writing is not without its flaws. Some jokes fall flat, and the game’s tone occasionally veers into surrealism for surrealism’s sake (e.g., the Fish King’s domain). The Cat Isle sequence, while visually striking, feels disjointed from the main narrative, a victim of the game’s non-linear ambitions.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Innovation and Frustration

The Smart Cursor: Simplicity at a Cost

Malcolm’s Revenge retains the Smart Cursor system from its predecessors, a context-sensitive interface that automatically changes based on the player’s interactions (e.g., “take,” “use,” “talk”). While this streamlines gameplay, it also removes a layer of player agency. Unlike LucasArts’ verb-based interfaces, which encouraged experimentation, the Smart Cursor often funnels players toward specific solutions, limiting creativity.

The Moodometer: A Gimmick with Depth

The game’s most innovative feature is the Moodometer, a slider that adjusts Malcolm’s honesty and moral alignment. This system allows players to:

– Lie shamelessly to manipulate characters.

– Tell the truth to gain trust or uncover hidden information.

– Adopt a neutral stance, balancing mischief and sincerity.

While the Moodometer is a brilliant concept, its execution is uneven. Many puzzles have only one viable solution, rendering the system more of a novelty than a core mechanic. However, in moments where it does matter—such as convincing the Pirate Captain to aid Malcolm—it shines, offering a rare sense of narrative agency in an otherwise linear genre.

Puzzle Design: The Double-Edged Sword of Non-Linearity

Malcolm’s Revenge is often praised for its multiple solutions to puzzles, a feature that sets it apart from its contemporaries. For example, escaping the junkyard at the game’s outset can be achieved in six different ways, from bribing a guard to constructing a makeshift hot air balloon.

However, this non-linearity comes at a cost:

1. Inventory Bloat: The game’s open-ended design encourages hoarding, leading to an unwieldy inventory filled with seemingly useless items. Players often struggle to discern which objects are relevant, leading to aimless experimentation.

2. Illogical Solutions: Some puzzles defy conventional logic. The prison escape sequence, for instance, requires players to use a flea (obtained by clicking on Malcolm after exposure to dogs) to distract a guard—a solution that feels arbitrary rather than clever.

3. Navigation Issues: The Cat Isle jungle maze is a notorious low point. The game’s isometric perspective and lack of a map make navigation needlessly frustrating, a flaw exacerbated by the fact that exiting a screen always deposits Malcolm at the bottom of the next, regardless of direction.

Combat and Progression: A Non-Existent System

Unlike many adventure games of the era, Malcolm’s Revenge features no combat and no character progression in the traditional sense. Malcolm’s growth is purely narrative, tied to his interactions and choices rather than statistical upgrades. This design philosophy aligns with the game’s focus on storytelling but may disappoint players expecting RPG-like mechanics.

The Point System: A Mockery of Sierra’s Tropes

The game includes a point system that awards players for completing actions, a nod to Sierra’s adventure games. However, the system is intentionally flawed: it is impossible to collect all points, a meta-commentary on the arbitrariness of such mechanics. This self-aware humor is a highlight, though it does little to enhance gameplay.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Feast for the Senses

Setting: Kyrandia as a Living, Breathing World

Malcolm’s Revenge expands the lore of Kyrandia, introducing new locations that feel distinct and immersive:

– The Junkyard: A grimy, cluttered starting point that reflects Malcolm’s fallen status.

– The Isle of Cats: A whimsical, almost surreal landscape ruled by feline overlords, a stark contrast to the game’s darker themes.

– The Underworld: A gothic, labyrinthine realm that serves as the game’s climax, complete with eerie sound design and oppressive architecture.

The game’s world-building is strengthened by its attention to detail. Environmental storytelling is evident in small touches, such as the graffiti in the junkyard (“Malcolm was here”) or the decaying grandeur of Brandon’s castle, which hints at the kingdom’s moral rot.

Visual Design: Pre-Rendered Ambition

The game’s pre-rendered 3D backgrounds were cutting-edge for 1994 but have not aged gracefully. While they lend the game a cinematic quality, the stiff animations and occasional texture warping detract from the immersion. Character sprites, however, are expressive and well-animated, particularly Malcolm, whose body language conveys his shifting emotions.

The art direction is a mix of fantasy and absurdity. The Cat Isle, with its oversized feline statues and pastel hues, feels like a fever dream, while the Underworld’s dark, jagged landscapes evoke a more traditional gothic horror aesthetic. This visual dichotomy mirrors Malcolm’s internal conflict.

Sound Design: Klepacki’s Haunting Melodies

Frank Klepacki’s soundtrack is a standout, blending orchestral fantasy themes with jazzy, almost vaudevillian motifs that reflect Malcolm’s jester persona. Tracks like the main theme and the Underworld suite are memorable, though some loops grow repetitive.

The game’s sound effects are equally impressive. The laugh track, while divisive, adds a layer of meta-humor, while ambient noises—creaking doors, distant howls—enhance the atmosphere. Voice acting is a mixed bag; Malcolm’s voice actor delivers a strong performance, but some secondary characters sound stiff or overacted.

Reception & Legacy: A Cult Classic’s Journey

Critical Reception: Praise and Backlash

Malcolm’s Revenge received mixed but generally positive reviews upon release, with critics praising its humor, innovation, and narrative ambition while criticizing its puzzle design and technical limitations.

- PC Gamer (88%): “Great characterizations; simple interface. Tricky puzzles; hilarious dialog; no single right way to win.”

- Next Generation (80%): “Brilliant visuals, a great sense of humor, and truly challenging puzzles.”

- Computer Gaming World (Unscored): Scorpia called it “refreshing in many ways, but also frustrating.”

The game’s MobyGames score (7.8) reflects this divide, with players and critics alike acknowledging its strengths while bemoaning its flaws.

Commercial Performance: Overshadowed by Strategy

Despite its critical acclaim, Malcolm’s Revenge was overshadowed by Westwood’s shift to strategy games. As Rick Gush noted, the studio’s management was more interested in Command & Conquer, leaving the adventure game under-marketed. Nevertheless, it sold over 250,000 copies by 1996, a respectable figure for the genre.

Influence and Legacy: The Antihero’s Shadow

Malcolm’s Revenge has had a profound but understated influence on adventure games:

1. Protagonist Subversion: It paved the way for games like The Wolf Among Us (2013) and Dishonored (2012), which explore morality through flawed protagonists.

2. Non-Linear Puzzles: Its multiple-solution approach influenced later titles, such as The Secret of Monkey Island: Special Edition (2009), which incorporated optional puzzle paths.

3. Meta-Humor: The game’s self-aware humor and fourth-wall-breaking elements foreshadowed the meta-narratives of Stanley Parable (2013) and Undertale (2015).

Yet, its legacy is often overshadowed by its contemporaries. While Monkey Island and King’s Quest are celebrated as genre-defining, Malcolm’s Revenge remains a cult favorite, beloved by those who appreciate its audacity but overlooked by the broader gaming community.

Modern Reappraisal: A Flawed Masterpiece

Modern reviews on platforms like GOG.com and Retro Replay reflect a growing appreciation for Malcolm’s Revenge as a flawed masterpiece—a game whose ambitions outstrip its execution but whose ideas remain ahead of their time.

- GOG User (Morturius): “It’s Malcolm. He is the bad guy with a golden heart, a mischief maker with an overweight bad conscience. I love this game just for him.”

- Retro Replay (7.8/10): “A captivating journey for both longtime fans and newcomers… a worthy capstone to the Legend of Kyrandia trilogy.”

The game’s ScummVM compatibility has introduced it to new audiences, many of whom appreciate its narrative depth despite its dated mechanics.

Conclusion: The Jester’s Last Laugh

The Legend of Kyrandia: Book 3 – Malcolm’s Revenge is a game of contradictions. It is brilliant yet flawed, innovative yet frustrating, hilarious yet melancholic. It dares to ask questions about morality and perception that few games of its era attempted, and it does so with a wit and charm that remain infectious nearly three decades later.

Its puzzles may confound, its mechanics may irritate, and its visuals may show their age, but its heart—the story of a misunderstood jester seeking redemption in a world that has already judged him—is timeless. In an industry that often prioritizes polish over ambition, Malcolm’s Revenge stands as a testament to the power of narrative risk-taking.

Final Verdict: 8.5/10 – A Cult Classic That Deserves a Second Act

While not without its faults, The Legend of Kyrandia: Book 3 – Malcolm’s Revenge is an essential play for adventure game enthusiasts and a fascinating study in subversive storytelling. It is a game that demands patience but rewards persistence, offering a narrative experience that lingers long after the credits roll.

For those willing to embrace its quirks, Malcolm’s Revenge is more than a game—it is a manifestation of the jester’s spirit: chaotic, unpredictable, and ultimately, unforgettable.

Recommended for: Fans of narrative-driven adventures, lovers of antiheroes, and those who appreciate games that challenge conventional storytelling.

Play it if you enjoyed: The Secret of Monkey Island, Grim Fandango, Planescape: Torment.

Avoid if you dislike: Illogical puzzles, dated graphics, or non-linear experimentation.

The jester’s tale may be over, but his laughter echoes on.