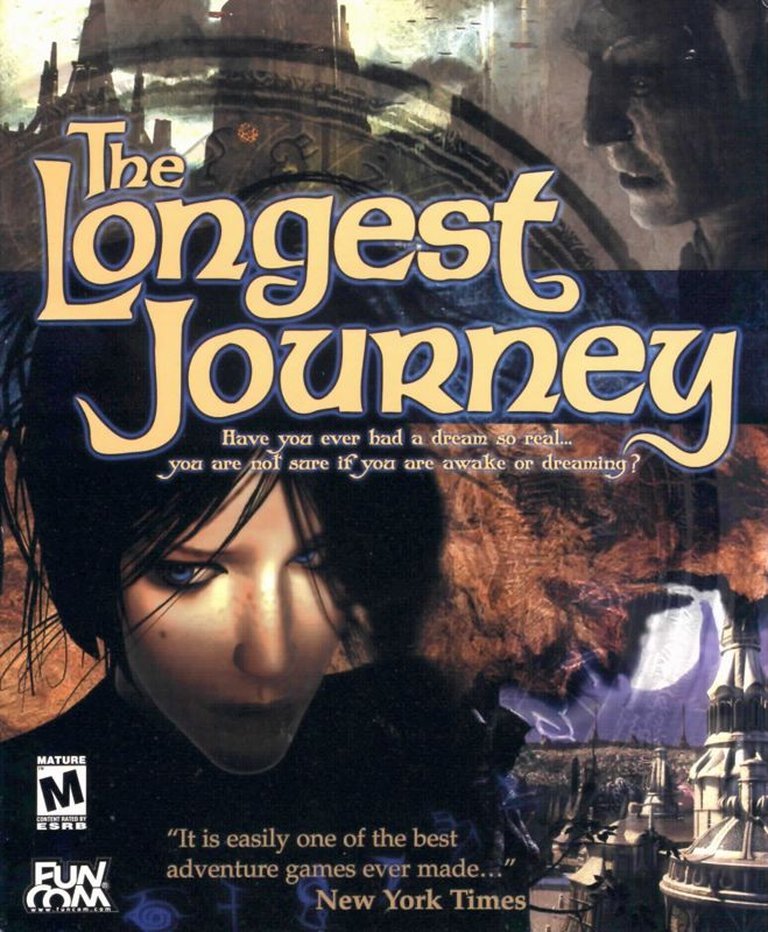

- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: iPad, iPhone, Windows

- Publisher: 1C Company, 1C-SoftClub, 3D Planet S.p.A., Egmont Interactive GmbH, Empire Interactive Entertainment, Empire Interactive Europe Ltd., Funcom N.V., Funcom Oslo A/S, FX Interactive, S.L., IQ Media Nordic AB, K.E. Media, Micro Application, S.A., R&P Electronic Media, Snowball.ru, Ubi Soft Entertainment Software

- Developer: Funcom Oslo A/S

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Graphic adventure, Point-and-click, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Cyberpunk, dark sci-fi, Fantasy

- Average Score: 93/100

- Adult Content: Yes

Description

The Longest Journey is a third-person graphic adventure game set in 2209, following April Ryan, a student artist who discovers she can shift between two parallel worlds: Stark, a cyberpunk dystopia of science and technology, and Arcadia, a fantasy realm of magic. After being hailed as the ‘mother of the future’ by a dream dragon, she must navigate both worlds, solve puzzles, and restore balance to prevent catastrophe, blending rich storytelling with point-and-click gameplay.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy The Longest Journey

PC

The Longest Journey Free Download

The Longest Journey Patches & Updates

The Longest Journey Mods

The Longest Journey Guides & Walkthroughs

The Longest Journey Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (91/100): The best adventure game in years.

reddit.com : I would recommend this game.

mobygames.com (88/100): Longest Journey is a beautiful game.

imdb.com (100/100): This is the most complete and beautiful adventure game ever.

The Longest Journey: Review

In the late 1990s, as the video game industry pivoted toward 3D action and online multiplayer, the graphic adventure genre seemed poised for obsolescence. Into this void stepped The Longest Journey, a game that not only defied the odds but also redefined what narrative-driven experiences could achieve. Developed by the Norwegian studio Funcom and released in 1999, this point-and-click masterpiece blended science fiction and high fantasy with a成熟ity rarely seen in games, anchored by one of the most compelling protagonists in the medium’s history. Over two decades later, its legacy endures as a benchmark for storytelling in games, even as its mechanics show their age. This review delves deep into every facet of The Longest Journey, from its ambitious development to its lasting impact, to argue that it remains a pivotal, if imperfect, landmark in video game history.

Introduction: A Journey Into the Soul of Adventure

The Longest Journey is not merely a game; it is an epic odyssey that transports players between the stark, neon-lit streets of a futuristic Earth and the lush, mystical realms of Arcadia. At its heart lies April Ryan, an art student who discovers she is a “Shifter” capable of traversing these parallel worlds, tasked with restoring a cosmic balance threatened by shadowy forces. From its opening moments, the game envelops you in a tapestry of rich lore, complex characters, and philosophical depth that challenges the player’s perception of reality, identity, and faith. My thesis is this: The Longest Journey is a flawed masterpiece—a game whose narrative ambition and thematic richness elevate it above its genre contemporaries, even as its gameplay mechanics and pacing reveal the constraints of its era. It stands as a testament to the power of storytelling in games, influencing a generation of developers and securing its place as a cornerstone of adventure gaming.

Development History & Context: Forging a New Path

The Studio and Vision

The Longest Journey was developed by Funcom Oslo A/S, a Norwegian studio previously focused on console titles like Casper. The project was spearheaded by Ragnar Tørnquist, then 25 years old, who served as writer, lead designer, and producer. Inspired by classic adventure games such as Day of the Tentacle and Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers, as well as literary works like Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman, Tørnquist aimed to create a mature, story-driven experience that eschewed the cartoonish aesthetics of many contemporaries. The game’s title references a quote by Dag Hammarskjöld: “The longest journey is the journey inward,” hinting at its introspective themes.

Technological Constraints and Innovations

Developed on a modest budget of $2–3 million, the team built a custom engine from scratch, facing significant technical hurdles. Pre-rendered 3D backgrounds (using 3D Studio Max) were paired with real-time 3D character models, a technique that allowed for stunning visuals but introduced integration challenges—characters sometimes appeared “pasted” onto scenes. The game spanned four CD-ROMs, reflecting the era’s storage limitations, and required a full installation of over 1GB, which was substantial for 1999. Despite these constraints, the team implemented user-friendly features like a context-sensitive cursor that flashed when an action was valid, reducing frustration, and a diary system for tracking key plot points.

Gaming Landscape at Release

The late 1990s saw the decline of the adventure genre, with major publishers shifting focus to 3D action and RPGs. Titles like Grim Fandango (1998) had reinvigorated interest, but the market was saturated with clones or failed experiments. The Longest Journey arrived as a breath of fresh air, offering a serious, adult narrative with a strong female lead—a rarity at the time. Its initial release was Scandinavia-centric (November 1999 in Norway), with gradual European rollout and a delayed North American launch in November 2000 due to distribution challenges. This regional strategy allowed word-of-mouth to build, particularly among adult audiences, as Funcom targeted “a more mature demographic” beyond the typical teenage market.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: A Symphony of Worlds and Words

Plot Structure and Pacing

The story unfolds across 13 chapters, weaving a nonlinear yet linear-narrative tapestry. April Ryan’s journey begins in Stark (a cyberpunk-infused 22nd-century Newport), where she experiences vivid dreams of a white dragon. Guided by the enigmatic Cortez, she discovers her ability to “Shift” into Arcadia, a high-fantasy realm governed by magic. The core conflict revolves around The Balance—a cosmic force separating Stark and Arcadia after Earth’s division millennia ago by the Draic Kin (dragon-like beings). A rogue faction, the Vanguard, seeks premature reunification, threatening both worlds with chaos. April must recover a replacement disc, rally allies, and ultimately confront the Guardian’s successor, Gordon Halloway, in a climax that merges logic with emotion.

The plot is dense with exposition, often delivered through lengthy dialogues that explore the lore of the Sentinel, the Draic Kin, and the prophecy of the Shifter. While some critics found this verbose, it serves to immerse players in a universe where every detail matters—from the history of the All-Tongue to the significance of the Chaos Vortex. The pacing is deliberate, with chapters dedicated to exploration, puzzle-solving, and character interactions that build emotional investment. The ending, while ambiguous and open-ended, emphasizes personal growth over cosmic resolution, leaving room for sequels like Dreamfall.

Characters: From Archetypes to Archetypal Depth

The Longest Journey shines through its ensemble cast, each with distinct motivations and arcs:

– April Ryan: The protagonist is a cynical, sarcastic art student with a troubled past (implied childhood abuse). Her voice, performed by Stephanie Kindermann (German version) or Synnøve Svabø (original Norwegian), balances wit with vulnerability. Unlike contemporaries like Lara Croft, April is not a hyper-sexualized action hero; her strength lies in her relatability, curiosity, and moral complexity. Her diary entries provide introspective commentary, though some players find her “ditzy” or whiny—a deliberate subversion of the “chosen one” trope.

– Cortez: The mysterious mentor figure, a Shifter from the 1930s, whose Spanish (or French in some localizations) heritage and cryptic guidance frame April’s quest. His revelation as a Draic Kin adds layers to his loyalty.

– Crow: A talking bird from Arcadia, serving as comic relief and loyal companion. His banter with April lightens darker moments, and his chronological omnipresence (as an elder in the epilogue) ties into themes of time and consequence.

– Abnaxus: A chair-bound being who exists outside linear time, his dialogue (“I will. I did.”) exemplifies the game’s playful engagement with temporal paradoxes.

– Antagonists: Jacob McAllen (a Draic Kin in disguise) and Gordon Halloway (the emotionally stunted Guardian successor) represent ideological extremes—unchecked ambition vs. cold logic—contrasted with April’s balanced humanity.

Supporting characters like Brian Westhouse (a whiskey-drinking expatriate), Tobias Grensret (a priest of the Vestrum), and Burns Flipper (a hacker) enrich the world with backstories revealed through dialogue, making even minor NPCs feel lived-in.

Dialogue and Writing: A Double-Edged Sword

The game’s dialogue is its most praised and criticized element. On one hand, it is exposition-heavy and lengthy—conversations can span minutes, with players choosing initial topics but then passively listening. This design prioritizes storytelling over interactivity, akin to reading a novel. The writing is mature, witty, and thematically rich, tackling subjects like faith, identity, and social justice (e.g., positive LGBTQ+ depictions, critiques of corporatism). April’s sarcastic asides and feminist remarks add levity, while philosophical monologues (e.g., Tobias on the Balance) elevate the discourse.

On the other hand, the lack of branching outcomes and static camera angles during dialogues can induce fatigue. As one critic noted, Planescape: Torment achieves similar depth with more player agency. The “talking puzzles” (e.g., retrieving four stories from Alatien villagers) feel like arbitrary time-fillers, stretching gameplay without meaningful choice. Yet, for narrative purists, this verbosity is an asset, creating emotional investment that pays off in the second half.

Themes: Balance, Duality, and Self-Discovery

At its core, The Longest Journey explores duality:

– Science vs. Magic: Stark represents logic, technology, and dystopian corporatism; Arcadia embodies chaos, nature, and mysticism. The game argues for interdependence, not opposition—both worlds are fractured without the other.

– Order vs. Chaos: The Vanguard’s dogma (pure logic) and the Chaos Vortex (pure anarchy) are extremes that April must reconcile.

– Identity and Agency: April’s journey is inward as much as outward; she grapples with her role as a Shifter, her past trauma, and her autonomy (“I’m not the chosen one you’re looking for”). Her art background symbolizes the fusion of creativity (Arcadia) and technique (Stark).

– Faith and Mythology: Religious motifs (the Guardian as a messiah figure, the Draic Kin as ancient gods) are woven into the lore, prompting reflections on belief in the unbelievable.

These themes are unusually mature for a 1999 game, addressing child abuse, drug addiction, and sexuality with nuance, albeit sometimes obliquely.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Tradition with Tweaks

Core Loop and Interface

The Longest Journey adheres to the LucasArts/Sierra template: point-and-click navigation on pre-rendered screens, inventory-based puzzles, and dialogue trees. The interface is streamlined—a cursor changes color (red for exits, light blue for interactive objects) and flashes when an item can be used, eliminating guesswork. The inventory is a “big-box-o’-stuff” system, with items combinable via drag-and-drop. A map facilitates travel between key locations, and the diary auto-updates with plot summaries, aiding recall.

Puzzles: Ingenious or Inane?

Puzzles range from logical environmental challenges to arbitrary inventory combinations:

– Strengths: Some puzzles integrate seamlessly with the narrative (e.g., using a pocket watch to return to Stark, deciphering All-Tongue runes). They often require observational skills—clues are hidden in dialogues or backgrounds.

– Weaknesses: The infamous rubber duck puzzle (grounding an electrical wire with a duck tied to a clamp) epitomizes the “cat mustache” syndrome—illogical, counterintuitive, and frustrating. Other puzzles rely on FedEx tasks (fetching items for NPCs) or dialogue-based solutions (the Alatien folk tales), which can feel like tedious padding. The game lacks “death” states, removing tension but also consequence.

Combat and Progression

There is no traditional combat; challenges are puzzle-based or stealth-oriented (e.g., evading the Gribbler). Progression is linear, with chapters gating access to new areas. Player agency is limited to dialogue choices (which rarely alter the main plot) and puzzle solutions (often single-path). This design emphasizes story over gameplay, aligning with Tørnquist’s vision of an “interactive novel.”

Innovations and Flaws

Innovations include:

– Cursor hints that reduce pixel-hunting frustration.

– Diary and conversation logs for narrative tracking.

– Voice-acted dialogue with options to toggle text/subtitles.

Flaws:

– Static camera angles during conversations limit cinematic immersion.

– Puzzle inconsistency—some solutions are absurd (e.g., infiltrating a police station via coincidental broken doors).

– Pacing issues: Lengthy dialogues and slow movement (April’s running speed) drag the experience.

– Bugs: Notably the “Police Station bug” (fixed via patch), and integration issues with 3D models on pre-rendered backgrounds.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Feast for the Senses

Stark and Arcadia: Contrasting Visions

The dual-world design is conceptually brilliant:

– Stark: A cyberpunk dystopia with hovercars, megacorporations, and privatized police. Visually, it channels Blade Runner and Brazil—rain-slicked streets, oppressive architecture, and neon signage. The Venice district feels claustrophobic, reflecting April’s urban alienation.

– Arcadia: A high-fantasy realm with floating islands, silver dragons, and organic magic. Landscapes like the Marcuria city (inspired by Yes album art) and the Fringe Café (a whimsical pub) exude wonder. The Norse aesthetic—vast, majestic, and cold—pervades, from snow-capped mountains to eerie swamps.

The thematic contrast is palpable: Stark’s logic breeds cynicism; Arcadia’s magic fosters mystery. Yet both worlds share moral ambiguity—Stark’s corporate greed vs. Arcadia’s patriarchal traditions—avoiding simplistic good/evil dichotomies.

Visual Direction: Pre-Rendered Beauty

The pre-rendered backgrounds are exquisitely detailed, hand-painted to evoke specific moods. Each location feels handcrafted, from the grimy subway to the ethereal Guardian’s realm. The 3D character models, while low-polygon by today’s standards, were advanced for 1999, with dynamic lighting that matched backgrounds. However, integration issues arise—characters sometimes appear “floating” or poorly aligned, and FMV cutscenes feature awkward animations (April’s facial expressions notably uncanny). The art direction remains timeless in its composition, but the tech shows its age on widescreen displays.

Sound Design and Music

Sound design is immersive and atmospheric: ambient noises (rain, city bustle, magical whispers) ground each world. The voice acting is a highlight—Stephanie Kindermann (English) and other localized actors deliver nuanced performances, especially April’s dry wit and Crow’s humor. Some critics note recycled voice actors (e.g., multiple characters sounding alike) and occasional stiff delivery, but the ensemble generally elevates the script.

The soundtrack by Bjørn Arve Lagim is universally lauded as one of gaming’s finest. It deftly blends electronic motifs for Stark with orchestral, ethereal themes for Arcadia, using leitmotifs to underscore emotional beats. Tracks like “The Balance” and “Shifting” are memorable and thematically resonant, enhancing immersion without overpowering.

Reception & Legacy: From Cult Classic to Canonical Masterpiece

Critical Reception at Launch

The Longest Journey received universal acclaim upon release, with an 88% average on MobyGames and 91/100 on Metacritic. Critics praised:

– Narrative and characters: April Ryan hailed as one of gaming’s strongest female leads; the story called “epic” and “mature.”

– Production values: Graphics, sound, and voice acting noted as top-tier for the genre.

– Themes: Applauded for tackling adult subjects ( sexuality, faith, abuse ) without sensationalism.

Criticisms focused on:

– Puzzle design: Illogical solutions (rubber duck) and over-reliance on dialogue.

– Pacing: Lengthy conversations and slow movement.

– Linear structure: Lack of meaningful choices.

It won Adventure Game of the Year from Computer Gaming World, GameSpot, IGN, and PC Gamer, among others, and was nominated for awards in sound design and storytelling.

Commercial Performance

Sales were modest but successful given the niche genre:

– Norwegian debut: 15,000 units shipped, sell-through high.

– Europe: 100,000 units by September 2000; Spain alone hit 50,000.

– North America: Delayed release limited sales to ~90,000 by mid-2001, but word-of-mouth boosted longevity.

– Global total: 500,000+ units by 2004, a significant figure for an adventure game. Funcom reported 50% female players, a demographic win for the era.

The game recouped its budget (150,000 units to break even) and became one of the best-selling adventures of its time, proving there was still a market for cerebral, story-rich experiences.

Evolution of Reputation

Over time, The Longest Journey has been reappraised as a classic:

– Retrospective praise: Frequently listed in “greatest games” compilations (1001 Video Games You Must Play Before You Die). In 2011, Adventure Gamers ranked it #2 best adventure game ever.

– Cult following: A dedicated fanbase sustained by sequels (Dreamfall, Dreamfall Chapters) and fan projects.

– Criticisms aged: Graphics and puzzles now seen as dated; the slow pace and linearity feel archaic compared to modern adventures. Yet its narrative ambition remains influential.

Industry Influence

The Longest Journey helped pave the way for narrative-driven games:

– It demonstrated that adult-themed stories with complex female leads could succeed commercially.

– Its blend of dual-world mechanics inspired later titles like BioShock Infinite (dimensional themes) and The Witcher (moral ambiguity).

– The “Shifter” concept and balance motif recur in fantasy/sci-fi hybrids.

– Directly spawned the Dreamfall series, which evolved the formula with 3D environments and deeper social commentary.

– Alongside Grim Fandango, it is cited as a last great classic of the point-and-click era, influencing indie adventures like The Blackwell Series and Sam & Max revivals.

Conclusion: A Flawed Jewel in Gaming’s Crown

The Longest Journey is a paradox: a game that is both a product of its time and timeless in its themes. Its narrative depth, character development, and atmospheric world-building set a benchmark for storytelling in games, proving that adventures could tackle mature subjects with nuance and poetry. April Ryan remains a landmark protagonist—flawed, witty, and human—in an industry often criticized for one-dimensional heroes. The sound design and soundtrack are masterclasses in immersion, while the dual-world concept remains conceptually rich.

Yet its gameplay flaws are undeniable: puzzles range from clever to absurd, pacing drags in places, and the static dialogue system feels antiquated. For modern players, the technical limitations (low-poly models, slow animations) may require patience. However, these imperfections do not diminish its core achievement: creating an interactive epic that prioritizes emotional and intellectual engagement over reflexes or repetition.

In video game history, The Longest Journey occupies a pivotal role. It was a last hurrah for the classic adventure genre, a bridge between the LucasArts golden age and the narrative-focused renaissance of the 2010s. Its legacy is twofold: as a cult favorite that inspired sequels and a devoted fanbase, and as a critical touchstone for what games can achieve as storytelling mediums. It is not perfect, but it is essential—a journey well worth taking, even if it tests your stamina. As Lady Alvane implies in the epilogue, the longest journey is inward, and The Longest Journey guides us there with wisdom, wonder, and a touch of magic.