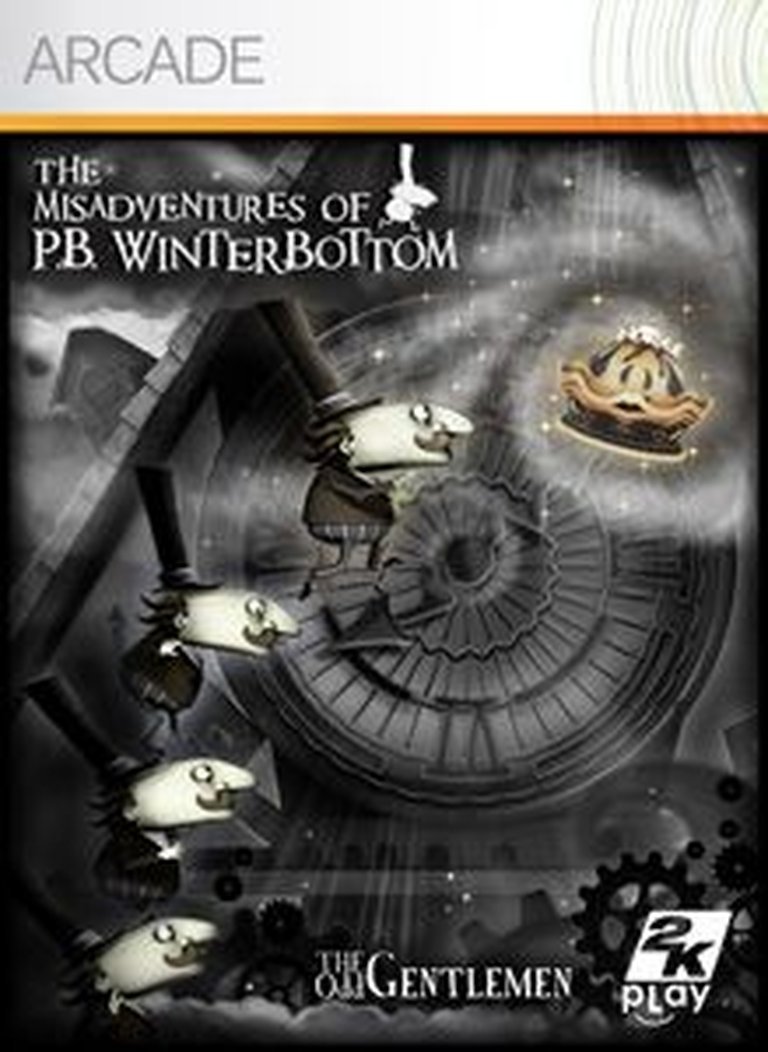

- Release Year: 2010

- Platforms: Windows, Xbox 360, Xbox One, Xbox Series

- Publisher: 2K Games, Inc.

- Developer: The Odd Gentlemen

- Genre: Action, Puzzle

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Cloning, Platforming, Puzzle-solving, Time manipulation

- Setting: Steampunk

- Average Score: 83/100

Description

The Misadventures of P.B. Winterbottom is a puzzle-platformer set in a stylized black-and-white silent film world with steampunk elements. Players control a pie-obsessed thief who manipulates time by recording and looping his actions to spawn cooperative clones, solving intricate puzzles to chase elusive pies while avoiding evil clones spawned by antagonistic pastries.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy The Misadventures of P.B. Winterbottom

PC

The Misadventures of P.B. Winterbottom Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (83/100): Like the very best puzzle games, this one gets in your head and refuses to leave.

ign.com : Winterbottom will both frustrate you and make you feel like a super brain.

The Misadventures of P.B. Winterbottom: A Masterclass in Temporal Pie-Theft and Silent Film Whimsy

Introduction: A Curious Time-Capsule of Indie Ingenuity

In the landscape of 2010’s digital storefronts, awash with remakes and budget re-releases, The Misadventures of P.B. Winterbottom emerged not as a mere product but as a perfectly preserved artifact of indie game design at its most confidently eccentric. It is a game that wears its influences—silent cinema, German Expressionism, and the nascent puzzle-platformer zeitgeist led by Braid—not as a badge of derivation, but as the foundational materials for something utterly singular. At its core lies a deceptively simple premise: a gluttonous Victorian thief must manipulate time to steal pies. Yet, from this whimsical seed grows a surprisingly dense and challenging arboreal structure of puzzles, all presented within a meticulously crafted black-and-white world that feels both antique and timeless. This review will argue that Winterbottom is a seminal work of interactive art, a game whose legacy is secured not by revolutionary mechanics alone, but by the profound cohesion between its narrative theme, its mechanical innovation, and its unparalleled aesthetic vision. It is a brilliant, if flawed, gem that captures a specific moment where indie development could ascend to the mainstream without sacrificing its idiosyncratic soul.

Development History & Context: From USC Thesis to XBLA Spotlight

The game’s origin story is a classic indie narrative, imbued with the academic rigor of its creators. Winterbottom began as a graduate thesis project at the University of Southern California’s Interactive Media & Games Division. A team of students—including Matthew Korba, Paul Bellezza, Asher Vollmer, Jamie Antonisse, and others—conceived the initial Flash game, The Misadventures of P.B. Winterbottom, as an exploration of time-manipulation mechanics within a comedic framework. This academic crucible is crucial: it meant the core mechanic—recording and looping one’s actions to create cooperative clones—was born from a focused, experimental design exercise, unburdened by commercial expectations.

This student project caught the eye of publishers, leading to the formation of The Odd Gentlemen as a studio to develop it commercially. Their collaboration with 2K Play for publishing was a significant boost, granting the game a prime spot on Xbox Live Arcade (XBLA) and a Steam release. This period, 2008-2010, was the golden age of the Xbox 360’s digital storefront, a platform actively seeking exclusive, high-quality indie titles to compete with PlayStation Network and establish itself as a home for creativity. Winterbottom arrived in the wake of Braid (2008) and Castle Crashers (2008), games that proved downloadable titles could be both critically acclaimed and commercially viable. The technological constraints were those of the era: a 2D sprite-based game builtlikely in Lua (as noted in MobyGames’ groups), targeting the XBLA’s 2GB size limit and the hardware of the Xbox 360 and mid-range PCs. This limitation fostered a minimalist, performance-focused design. The choice of a monochrome palette was both an artistic statement and a practical one—it reduced asset creation time while maximizing visual distinctiveness in a crowded market. The game’s success (over 35,000 estimated units sold, per GameRebellion) demonstrated that a small team with a singular vision, backed by a major publisher’s distribution, could thrive.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Gluttony, Time, and the Silents

Narratively, Winterbottom is a masterclass in economical, absurdist storytelling. There is no dialogue; the entire plot is delivered through rhyming, poetic title cards between levels, rendered in a beautiful, hand-illustrated style by concept artist Vincent Perea. These cards, reminiscent of early 20th-century intertitles, are not mere exposition but a core part of the game’s comedic and thematic fabric. They establish P.B. Winterbottom not as a heroic protagonist but as a “notorious thief with an insatiable hunger for pies,” a portly, gluttonous anti-hero whose pursuit of the “Chronoberry Pie” is less about heroism and more about base, comedic desire.

The inciting incident is a perfect twist on the “forbidden fruit” myth: Winterbottom bites into a mysterious, sentient pie and is “cursed,” gaining the power to manipulate time. This reframes his pie-stealing from simple theft into a temporal paradox-creation spree. The underlying themes are rich and multi-layered. On the surface, it’s a slapstick chase comedy, echoing the physical humor of silent film stars like Buster Keaton or Charlie Chaplin, whom Winterbottom’s clumsy, determined persona evokes. Deeper, it explores the paradox of self-cooperation—the player must work with past, present, and future versions of themselves. This mechanical imperative becomes a thematic core about the fragmentation of self and the consequences (or “misadventures”) of one’s actions across time.

The introduction of “evil pies” in advanced levels is a narrative and mechanical masterstroke. These sentient pastries don’t just act as obstacles; they spawn “evil clones” that replicate the player’s own path to steal the pie first. This mechanizes the game’s central irony: the very act of pursuing your goal creates an antagonistic version of yourself. It’s a literalization of the “shadow self,” a concept deeply rooted in psychology and literature, rendered here as a mischievous, competitive pastry. The absence of traditional enemies focuses the narrative entirely on Winterbottom’s internal (and now externalized) conflict with his own temporal echo.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Elegant Complexity of Self-Cooperation

The genius of Winterbottom lies in its mechanical simplicity evolving into profound complexity. The control set is finite: move, jump, use an umbrella to float/flick, and interact with springs/portals. The transformative ability is time recording. By holding a trigger, the player records a sequence of actions; upon release, a clone is created that loops that sequence indefinitely. This single system is the keystone for every puzzle.

The puzzle design is where the game shines and stumbles. Initially, players use clones as simple platforms or to hit distant switches. Quickly, the game introduces constraints: limited clone slots, portals that only allow recording within them, or the requirement to “whack” (interact with) clones to remove them. The true depth emerges from the rule that clones are persistent, interactive objects regardless of when they were created. A clone from “five minutes ago” in puzzle time exists on the screen alongside the “present” Winterbottom and can be jumped on, hit, or used to trigger switches. This creates puzzles where you must choreograph a ballet of multiple temporal selves.

The “evil pie” mechanic adds a brilliant layer of adversarial self-simulation. Grabbing one spawns an evil clone that follows your exact recorded path. To collect subsequent pies, you must alter your route to avoid being intercepted by your own doppelgänger. This escalates the cognitive load from cooperative puzzle-solving to competitive, route-planning challenges against a perfect, memory-based copy of yourself.

However, this depth comes at a cost. The difficulty curve is notoriously steep and, for many, fatiguing. As IGN noted, the puzzles can be “exhausting to the point that you aren’t motivated to continue.” The solutions often require extreme precision and sequences so long that a single mistiming means restarting the entire recording chain. Unlike Braid, which often allowed for more organic exploration, Winterbottom can feel like a “trial-and-error” gauntlet, as 4Players.de criticized. The lack of a gentle hint system means players can hit “frustration walls” where progress halts for extended periods. The game’s length (around 2-4 hours for the main 80+ puzzles, per multiple reviews) is often cited as a pro (value for money) and a con (lack of sustained content), but the real issue is not quantity but the mental bandwidth required for its later puzzles, which can make the experience feel longer and more grueling than it is.

The user interface is clean and diegetic, fitting the silent film theme, but the controls were occasionally cited as “sluggish” (GameSpot) or “a bit awkward,” particularly in high-pressure moments requiring precise jumps onto moving clones. This slight disconnect between the elegant design and the physical input is a notable blemish on an otherwise precise system.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Monochrome Masterpiece

If the gameplay is the brain of Winterbottom, its presentation is its soul. The game is a love letter to silent cinema and German Expressionism. The entire visual palette is black-and-white, with a persistent film-grain filter, scratches, and vignette effects that make it look projected in a turn-of-the-century theatre. This is not a stylistic veneer; it is the foundational language of the game’s world.

Concept artist Vincent Perea’s work is central here. The characters and environments are drawn with a grubby, industrial elegance. Buildings have sharp, distorted angles reminiscent of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari; backgrounds are often paper-diorama layers (Destructoid‘s observation). The title cards between levels, featuring Perea’s illustrations and rhyming poetry, are beautiful narrative vignettes that break up gameplay and deepen the world. The level select is styled as a series of vintage movie posters, each for a different “film” (world), a wonderful touch that reinforces the meta-narrative.

The sound design and music by David Stanton are equally pivotal. The soundtrack is a collection of piano-centric, big-band arrangements that evoke the frenetic, whimsical energy of a silent film accompaniment. It is “Elfman-esque” (IGN), alternately mischievous, melancholic, and chaotic, perfectly underscoring Winterbottom’s chaotic misadventures. The use of silence and audio cues (like the “whack” sound when interacting with a clone) is precise and satisfying.

This aesthetic does more than please the eye and ear; it reinforces the gameplay’s temporal themes. The flickering film grain suggests the unreliability and passage of time. The monochrome palette flattens the visual field, making the spatial relationships between clones—which exist at different points in a recorded timeline—more legible. The old-timey presentation constantly reminds the player they are controlling a character trapped in a “movie,” a fiction whose rules they are breaking by creating temporal paradoxes. It is a total work of art (Gesamtkunstwerk) where every pixel and note serves the experience.

Reception & Legacy: Critical Darling, Cult Classic

At launch, The Misadventures of P.B. Winterbottom was met with strong critical acclaim, though not without reservations. Its Metacritic scores of 83 (Xbox 360) and 79 (PC) indicate “generally favorable reviews.” The praise was consistently directed at its bold aesthetic and inventive puzzle design. Eurogamer called it “supremely confident,” praising its unique identity beyond Braid comparisons. GameSpy’s 4.5/5 review famously used the pie metaphor: it has “both a delectable crust and a delicious filling.” 1Up.com gave it a rare A+, stating the “carefully crafted setting” made it “terrific.”

However, the criticisms were consistent and valid. The most common were its short length and * punishing difficulty. *GameSpot‘s 7.5/10 explicitly called out “sluggish” controls and “uneven difficulty.” 4Players.de noted that “minutenlange Trial&Error-Exzesse” (minutes-long trial-and-error excesses) could derail progress. The Pixel Empire retrospective was particularly harsh, arguing the puzzles often felt “obscure and difficult to formulate” and that the game lacked the “magnetism” for long-term play, scoring it 6/10.

Its commercial performance was modest but successful for a niche XBLA title. The sale to 2K Play and subsequent Steam release (at a persistent low price, now $2.49) ensured a long tail. Its legacy is nuanced. It did not achieve the cultural penetration of Braid or Portal. It did, however, solidify the puzzle-platformer as a viable genre for digital distribution and demonstrated that a game could be thematically and aesthetically cohesive from stem to stern. Its “recording-clone” mechanic has been cited as an influence on later titles that explore parallel timelines and self-cooperation, though it remains a distinct branch on the game design tree. The IndieCade Story/World Design award (2008) it won while still a student project foreshadowed its acclaim. Today, it is remembered as a cult classic—a game whose ardent fans champion its brilliance, while others recall it as a frustrating, brief aberration. On Steam, it maintains a “Very Positive” rating (88% from nearly 400 reviews), a testament to its enduring appeal for those who connect with its specific, demanding frequency.

Conclusion: A Flawed, Indelible Gem

The Misadventures of P.B. Winterbottom is not a perfect game. Its difficulty can mutate from engaging to punitive, its length is brief, and its controls occasionally betray the precision its puzzles demand. Yet, to dismiss it on these grounds is to miss its monumental achievement in synthesis. It is a rare game where mechanics, narrative, and aesthetic are not just aligned but fused at the atomic level. The act of recording a clone to solve a puzzle isn’t just a gameplay hook; it is the literal manifestation of Winterbottom’s cursed temporal state and the thematic core of self-competition. The silent film aesthetic isn’t window dressing; it visually codes the entire experience as a nostalgic, theatrical misadventure, softening the blow of frustration with relentless charm.

In the canon of puzzle-platformers, it stands not as a peer to Braid‘s philosophical weight or Portal‘s surgical perfection, but as its own entity: a kaiju-sized pie-obsessed id let loose in a beautifully constrained toybox of time. It is a testament to the power of a strong, weird vision executed with near-total consistency. For the player with the patience to match its wits, Winterbottom offers a profoundly rewarding experience—the “eureka!” moments are hard-won and sweet as cherry pie. It is a game that understands its own identity completely and refuses to compromise. For that reason, above its minor flaws, it deserves its place as a landmark title in the history of independent game design: a delicious,不法 (lawless), and unforgettable confection.

Final Verdict: 8.5/10 – A singular, stylistically flawless puzzle masterpiece held back by a punishing and sometimes unforgiving difficulty curve.