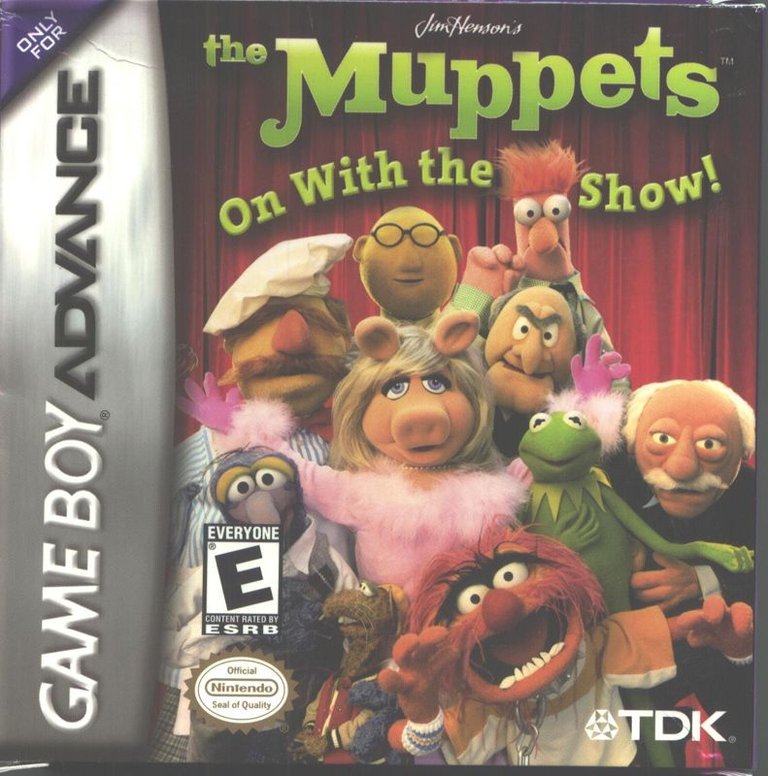

- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Game Boy Advance, Windows

- Publisher: TDK Mediactive, Inc.

- Developer: Activision Publishing, Inc., Vicarious Visions, Inc.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Evasion, Fighting, Music, Puzzle, Racing

- Setting: Muppets

- Average Score: 67/100

Description

The Muppets: On with the Show is a 2003 action game for Windows and Game Boy Advance, designed for young players. In this kid-friendly title, gamers help Kermit and the Muppets crew produce a new episode of their iconic TV show by completing six main activity games and unlocking two hidden minigames. Gameplay features a variety of simple challenges—including racing, fighting, music-making, and evasion—presented in a side-view format with clear instructions and star-based scoring. The game captures the humor and nostalgia of the original series, with references like Statler and Waldorf’s balcony banter, offering a lighthearted but straightforward experience focused on accessibility for children.

Gameplay Videos

The Muppets: On with the Show Free Download

Game Boy Advance

The Muppets: On with the Show Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (65/100): The game isn’t a bad little game for its target audience…but old-school Muppet fans and experienced gamers shouldn’t expect a whole lot of deep gameplay.

ign.com (70/100): It’s a group of cool little GBA mini-games, but it’s for the short attention span kid demographic.

The Muppets: On with the Show Cheats & Codes

Game Boy Advance (GBA)

Enter passwords via the Continue menu’s password entry screen. For Code Breaker codes, use a GameShark/Code Breaker device with the Master Code enabled.

| Code | Effect |

|---|---|

| 000098F5 000A | Master Code – Must be enabled for other Code Breaker codes to work |

| 10000270 0007 | Master Code – Must be enabled for other Code Breaker codes to work |

| 82004A44 003C | Infinite Time |

| 74000130 03FB | Press Select For Low Time |

| 82004A44 0001 | Press Select For Low Time |

| 32004A68 0004 | Infinite Health |

| J09J4 | Unlock All Mini-Games |

| G07n0 | Medium Difficulty Setting |

| H08L2 | Hard Difficulty Setting |

| bLGyq | Start Game at Level 2 (Swedish Chef Cooking Hour) |

| GWLd8 | Start Game at Level 3 (Muppet Labs) |

| L5qWS | Start Game at Level 4 (The Great Gonzo) |

| qFZ7F | Start Game at Level 5 (Jurassic Pork) |

| b7Ztv | Start Game at Level 6 (Electric Mayhem) |

| GH75H | Start Game at Level 7 (Rock With The Band) |

The Muppets: On with the Show: A Historic Review of Chaotic Charm and Shallow Gameplay

Introduction: The Greatest Show in a Cartridge, or Just a Flea Circus?

In the vast, often cynical archives of licensed video games, titles based on Jim Henson’s Muppets occupy a curious niche. They are not mere cash-grabs; they are attempts to bottle lightning—to translate the anarchic, puppet-driven chaos of The Muppet Show into interactive digital form. The Muppets: On with the Show!, released in 2003 for the Game Boy Advance (and Windows), stands as a definitive, if flawed, artifact of this endeavor. Developed by Vicarious Visions for the GBA—a studio then riding high on the success of its Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater ports—and published by TDK Mediactive, the game is not a sprawling adventure but a compact, eight-minigame compilation. This review argues that On with the Show! is a fascinating historical case study: a game that perfectly captures the aesthetic and character of its source material through impressive technical achievement for its platform, yet fundamentally misunderstands the gameplay legacy of the Muppets, settling for a simplistic, short-lived experience aimed squarely at preschoolers. Its true significance lies not in its quality, but in what it reveals about the early-2000s licensed game market, the constraints of the Game Boy Advance, and the persistent challenge of adapting televised surrealism into interactive mechanics.

Development History & Context: Puppets on a Pocket-Sized Stage

The early 2000s represented a twilight period for the Muppets franchise. Following Jim Henson’s 1990 passing and a series of underperforming films, the property was in a state of managed nostalgia, its cultural relevance maintained through syndication and carefully curated merchandise. Game developers continued to see value in the license. The Muppets: On with the Show! arrived on the GBA in March 2003, hot on the heels of Muppet Pinball Mayhem (2002) and alongside Spy Muppets: License to Croak and Muppets Party Cruise—all published by TDK Mediactive, which had secured the license from The Jim Henson Company. This glut of titles suggests a strategy of saturation, treating the Muppets not as a singular creative property but as a brand to be deployed across multiple, low-risk game genres.

The GBA version was handled by Vicarious Visions, a developer emerging as a premier second-party studio for Nintendo’s handheld. Fresh from the Tony Hawk and Crash Bandicoot GBA ports, they were masters of squeezing colorful, smooth-running sprite-based graphics from limited hardware. The Windows version was developed by Activision, likely a parallel project using similar assets. The technological constraints of the GBA were significant: a 16-bit processor, limited RAM, and no 3D acceleration. Vicarious Visions’ solution was pre-rendered 3D models converted into detailed, multi-directional sprites—a technique that allowed for large, expressive character models and fluid animation, a clear technical boast for the game.

The gaming landscape of 2003 was minigame-obsessed. The phenomenal success of Mario Party on Nintendo 64 had birthed a sea of party and compilation titles. On with the Show! squarely enters this arena, framing itself as “a new Muppet Show” where each minigame is a “scene.” This was a logical, low-friction design choice for a handheld game aimed at short play sessions, but it also reveals a critical lack of ambition. Instead of inventing a new genre that suit the Muppets’ chaotic spirit, the developers settled for recycling established minigame templates (rhythm action, Frogger, Excitebike-style racing, whack-a-mole) and skinning them with Muppet aesthetics.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Show Must Go On… Very Briefly

The game’s narrative is not a story but a format. It directly mimics the structure of the original 1976–1981 television series. There is no overarching plot; instead, a “show” must be put on, and each minigame is a “skit” or “act” featuring a specific Muppet character facing a mundane crisis elevated to absurdity. The framing device is pure Muppet Show: backstage vignettes featuring Kermit introducing the next act, with the relentless, sardonic heckling of Statler and Waldorf from the stately balcony concluding every round. This is where the game’s thematic heart beats strongest. The source material is not just referenced; it is structurally replicated. The game understands that the Muppets’ appeal lies in their volatile, dysfunctional chemistry, the constant threat of backstage disaster, and the meta-humor of a show perpetually on the brink of collapse.

Each minigame’s premise is a distilled essence of its protagonist:

* Kermit’s Banjo Bayou: A Frogger variant where the perpetually flustered host must navigate a river of chaos (penguins, chickens, Fozzie, and the rampaging Miss Piggy) while trying to make music. It reflects Kermit’s role as the beleaguered ringmaster trying to maintain order in a world of random obstacles.

* Swedish Chef’s Cooking Hour: A whack-a-mole style game where the Chef must fend off Rizzo the Rat and friends stealing his inedible ingredients. The Chef’s violent, linguistically garbled responses to the theft are perfectly in character, and the inclusion of random, non-food objects (a boot, a bowling ball) captures his surreal culinary approach.

* Electric Mayhem Band: A rhythm game where Animal, Janice, and Floyd (Zoot is oddly absent) perform, and the player must replicate a sequence of drum and guitar riffs. This is the game’s most direct attempt at simulating the actual performance aspect of the Muppet Show, channeling the band’s chaotic, jam-based energy.

* Gonzo’s Stunt Race: An Excitebike-like racing game where the eccentric daredevil must hit targets and avoid obstacles on a track, all while his vehicle gradually breaks down. This epitomizes Gonzo’s brand of self-destructive, inexplicable spectacle.

* Muppet Labs (Beaker): A frantic conveyor-belt sorting game where Beaker must remove Bunsen Honeydew’s toxic trash while preserving the essential green fluid. The visual of Bunsen silently panicking in the background is a perfect, silent-comedy encapsulation of their disastrous inventor-assistant dynamic.

* Jurassic Pork: A simple action game where Miss Piggy must karate-chop projectiles thrown by a giant “dinosaur pig” to rescue Kermit. It’s a pure fantasy of Piggy’s violent, possessive devotion to her frog, rendered with over-the-top, renaissance-era graphics that heighten the absurdity.

* Bonus Games (Fozzie’s Joke Avoidance & Pigs in Space): These unlockables further mine deep-cut references. Fozzie’s game—avoiding falling debris while telling bad jokes—is a direct callback to the “Fozzie’s Command” parody from Muppets Inside (1996). Pigs in Space is a straightforward shoot-’em-up evading asteroids, fulfilling a fan-service wish.

The underlying theme is consistent: competence is impossible, chaos is the default state, and success is measured merely in survival and basic task completion, not excellence. This is a brilliant thematic translation. However, the gameplay fails to engage with these themes on a systemic level. Missing Piggy doesn’t make Kermit’s boat harder to steer; she’s just a instant-fail obstacle. Beaker’s sorting is mechanical, not a comedic struggle. The games simulate the scenarios but not the comedic tension that defines the Muppets. The narrative is a charming facade, but the mechanics beneath it are generic.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Simple, Stupid, and Short

The core gameplay loop is as follows: select a minigame (initially six in Story Mode), read a one or two-sentence text intro explaining the premise, play a timed challenge, receive a star rating (out of five), and watch Statler and Waldorf deliver a pun. Repeat. The activities are genuinely simple, requiring basic motor skills: directional movement, button timing, object avoidance, or pattern recognition (Electric Mayhem). The three difficulty settings (Easy, Medium, Hard) primarily increase speed and frequency of obstacles, a standard and effective scaling method for children’s games.

The two most significant systemic flaws, universally condemned by critics, are:

- The Complete Absence of a Scoring or Persistence System: There is no high score table, no timer to beat, no points to accumulate that carry over. You play a minigame, get a star rating (based on a vague performance threshold), and that’s it. AllGame’s review pinpointed the consequence: “no battery backup to save best times, points, or top achievements… no incentives for repeat visits.” This renders each session an isolated event with no legacy, no goal beyond “finish it.” It is a design choice that actively fights against replayability, a cardinal sin for any game, especially a compilation.

- The Password Save System’s Critical Flaw: While a five-character password is a standard GBA-era compromise, the game commits a baffling error. As IGN’s review harshly noted: “the game doesn’t keep the last password earned in memory, so if players skip past the screen that offers their keyword… they can’t pull it up anywhere else.” This transforms a simple concession into a genuine annoyance, forcing players to meticulously write down every earned password or risk losing all Story Mode progress. It shows a fundamental disrespect for the player’s time and effort.

The Activity Mode—where unlocked minigames can be played freely—is the only saving grace, but its value is hollow without a reason to play them freely. The “perfect score to unlock” condition for the bonus games is the only real challenge, but without a score to cherish, achieving it feels like a task, not an accomplishment. The controls are generally responsive, though Electronic Gaming Monthly’s critique that characters feel unresponsive to input has some merit in faster, twitch-based games like Gonzo’s race or Miss Piggy’s battle. The minigames exist in a vacuum of purpose. They are not competitive, not score-attack, not puzzle-based with a solution to discover. They are pure, ephemeral skill checks that evaporate the moment they end.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Visual and Auditory Love Letter

Where On with the Show! unequivocally succeeds is in its presentation. This is a game made by and for Muppet fans. Vicarious Visions employed pre-rendered 3D models for all sprites, a technique that results in remarkably detailed, large, and smoothly animated characters on the GBA’s small screen. The Muppets are instantly recognizable in their proportions and movements: the Swedish Chef’s wobbly, chopping gait; Animal’s frenetic, drumming limbs; Gonzo’s lanky, reckless scoot. The variety of animations for success, failure, and idle states is impressive for the hardware.

The art direction faithfully recreates key locations: the backstage corridor, the Electric Mayhem’s on-stage setup with the iconic red curtain, Muppet Labs’ hazardous interior, and the pseudo-medieval setting of Jurassic Pork. The background details are packed with easter eggs: chickens and penguins—stand-ins for the nonsensical extras of the show—populate nearly every scene. Statler and Waldorf are ever-present in their balcony box, their heckling delivered via text that perfectly mimics their withering wit. This attention to environmental detail makes each minigame feel like a living slice of the Muppet Theater.

The sound design is another triumph. The game is saturated with authentic, digitized sound bites from the original show—Kermit’s “Yay!”, Fozzie’s “Wocka wocka!”, the Swedish Chef’s “Bork Bork Bork!”, Animal’s “DRUM!”. These samples are used contextually and comedically, triggering on specific actions to great effect. The music, composed by Bart Roijmans, is original but heavily stylized after the show’s jazzy, brassy, and chaotic themes. The Electric Mayhem minigame’s song is a particularly good pastiche. The only audio flaw is the inevitable repetition of short music loops during longer minigames, a hardware-mandated limitation.

Together, the graphics and sound create an atmosphere dripping with Muppet flair. For a nostalgic player, it is a potent experience. You are not just playing a game; you are spending time in a digital diorama of the Muppet Theater. The technical execution here is arguably the game’s most historically significant achievement—it proved the GBA could render complex, cartoon-licensed characters with fidelity and personality.

Reception & Legacy: Mixed Reviews, Faded Memories

Upon release in early 2003, On with the Show! was met with a chorus of “mixed or average” reviews. Metacritic’s 65% (based on 8 critic reviews) and MobyGames’ 44% (based on 6 critic reviews) both reflect a consensus, but with a notable split in score distribution. The divergence is telling:

* The Positive camp (IGN 70%, Nintendo Power ~72%, Pocket Games 70%): These reviews acknowledge the game’s target audience explicitly. IGN’s Craig Harris states it is “for the short attention span kid demographic” and “a decent one for that group.” They praise the charm, the faithful aesthetics, and the simple pick-up-and-play nature. Nintendo Power’s comment that activities are “simple enough for young players to understand, but engaging enough for all players to enjoy” captures this moderate optimism.

* The Negative camp (GameSpy 40%, 64 Power 27%, GameCola.net 12%, Game Informer 55%): These critics lambaste the game for its profound lack of depth. The 64 Power review’s German summation is brutally accurate: “Furchtbar simpel, furchtbar einfach und vor allem furchtbar schnell vorbei” (Terribly simple, terribly easy, and above all terribly short). The lack of a save system and scoring is repeatedly cited as a deal-breaker that kills any lasting interest. Game Informer’s verdict that the “games just aren’t much fun” cuts to the core issue: thematic window dressing cannot compensate for shallow mechanics.

Commercially, it was a budget title, forgotten almost immediately. Its legacy is confined to being one of several forgettable Muppet games from the TDK era (2002-2003). It did not reinvigorate the franchise, nor did it establish a template for successful Muppet games. That would come later, with more ambitious (and also poorly received) titles like Muppets Party Cruise. In the broader history of licensed games, On with the Show! is a representative example of the “competent but soulless” adaptation common before the industry’s licensed-game renaissance of the late 2000s/2010s. It prioritized asset fidelity and brand recognition over gameplay innovation, targeting the lowest common denominator (young children) while offering nothing for the nostalgic adult fan beyond visual recognition. The Kotaku listing’s description—”Help the Irresistible Muppets keep the show going…”—summarizes its entire premise: a series of trivial crises with no stakes, mirroring the show’s chaos but none of its cleverness or risk.

Conclusion: A Curiosity of Constrained Potential

The Muppets: On with the Show! is a game of two halves. One half is a technical showcase and love letter, a game that understands the Muppets’ visual and auditory language better than almost any of its contemporaries. The sprite work is exemplary for the Game Boy Advance, and the integration of classic sound bites and character animations is a masterclass in audiovisual license management. For a fan, the simple act of seeing Gonzo scoot across a track or the Swedish Chef bonk a rat with a skillet is a moment of genuine, warm recognition.

The other half is a gameplay void. It is a collection of rudimentary, disconnected micro-challenges that fail to engage beyond the most immediate, childlike level. The absence of any persistence, scoring, or meaningful progression is not a simplification but a fatal flaw, a design decision that ensures the game has no shelf life beyond a single, 20-minute Story Mode run. It respects the Muppets’ form but entirely misses the substance of their comedy—which is rooted in failure, improvisation, and chaotic cause-and-effect. Here, cause-and-effect is minimal and predictable.

Historically, its place is secure as a curio: a technically adept, aesthetically faithful, but fundamentally shallow entry in the Muppets’ gaming pantheon. It demonstrates the peak of what GBA-era Vicarious Visions could do with a license, but also the depth-first, brand-second mentality that plagued so many licensed games. It is a game to be appreciated for what it looks and sounds like, mourned for what it could have been. For the historian, it is a clear marker of 2003’s market: a budget-priced, kids-targeted minigame compilation riding the coattails of a beloved property, destined to be a footnote. Its ultimate verdict is one of poignant potential unrealized: a game that perfectly looks like the Muppet Show, but can never, ever be the Muppet Show.

Final Score: 5.8/10 (Reflecting its status as a technically competent but creatively bereft historical artifact).