- Release Year: 2009

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: 1C Company, Tale of Tales BVBA, TransGaming Technologies Inc.

- Developer: Tale of Tales BVBA

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: Behind view

- Game Mode: Co-op, Single-player

- Gameplay: Graphic adventure, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Fairy tale, Forest

- Average Score: 78/100

Description

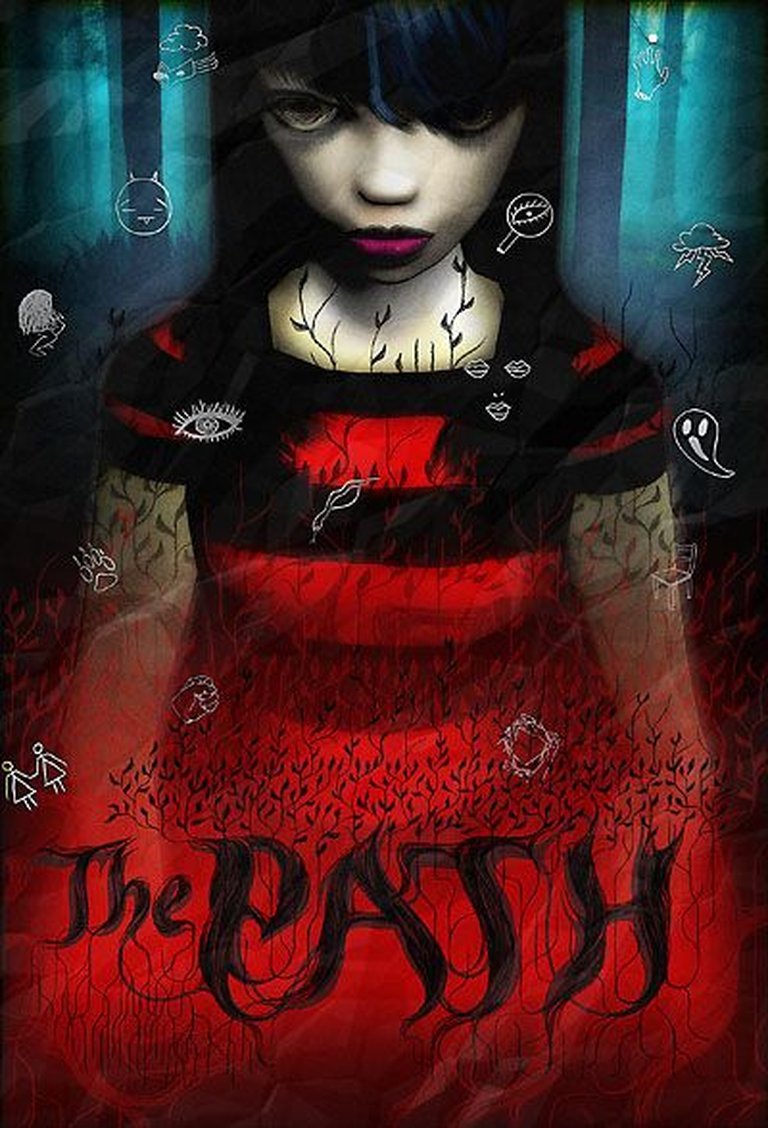

The Path is an unconventional psychological horror game inspired by the fairy tale Little Red Riding Hood and a 14th-century French grandmother’s tale. Players control one of six sisters, aged nine to nineteen, as they journey from home to grandmother’s house via a path, but true exploration requires venturing into an endless, randomized forest filled with haunting sound and visuals. Through minimalistic interactions with abandoned objects and key locations, the game reveals fragmented stories and memories via text and gestures, focusing on themes of growing up, fear, and player interpretation in an atmospheric, open-ended setting.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy The Path

PC

The Path Patches & Updates

The Path Guides & Walkthroughs

The Path Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (79/100): It will be years before a game made by the big budget software houses like Ubisoft or EA is brave enough to attempt anything remotely similar, but The Path shows promising signs that gaming is starting to grow up.

eurogamer.net : The Path is a videogame that isn’t a game.

mobygames.com (77/100): Not for everyone, but will appeal to story-driven Adventure gamers.

The Path: A Walk Through the Uncanny Valley of Growing Up

Introduction: The Wolf at the Door of Interactive Storytelling

In the canon of video games that strive for artistic legitimacy, The Path stands as a stark, beautiful, and profoundly divisive forest. Released in 2009 by the Belgian duo Tale of Tales (Auriea Harvey and Michaël Samyn), it is not merely an adaptation of Little Red Riding Hood but a deliberate deconstruction of the fairy tale’s psychological underpinnings and, by extension, the very language of video games. It rejects power fantasies, clear objectives, and satisfying mechanical loops, instead offering a slow, contemplative, and often unsettling trudge through a metaphorical woods where the true horror is not a wolf, but the burden of self-knowledge and the irreversible passage into adulthood. Its legacy is that of a landmark—a game that fervently argued for the medium’s capacity to articulate complex, adult themes of sexuality, loss, and identity, yet one whose execution is as famously flawed as it is brilliant. This review will argue that The Path is an essential, if uncomfortable, historical artifact: a passionate but uneven experiment that proved games could evoke the open-ended, personal resonance of literature or film, while also exposing the commercial and cultural tensions inherent in that pursuit.

Development History & Context: From Net Art to Commercial Quagmire

The Studio and the Vision: Tale of Tales emerged from the net.art scene of the late 1990s, with Harvey and Samyn building a reputation for poetic, browser-based interactive pieces. Their manifesto, the Realtime Art Manifesto (2006), declared their intent to use real-time 3D not for spectacle, but for “experiences that are emotionally and intellectually engaging.” The Path, initially codenamed 144 (a number that would eventually signify the 144 collectible “coin flowers”), was conceived as part of an abandoned series of fairy tale games following their first project, 8 (based on Sleeping Beauty). The pivot to a Little Red Riding Hood horror game was pragmatic—it was categorizable, trendy in its gothic-lolita aesthetic, and had a built-in cultural resonance.

Technological Constraints and the “Punk Economy”: With a microscopic budget compared to AAA titles (ultimately around €300,000, largely from arts grants like Creative Capital and the Flemish Audiovisual Fund, plus a loan), Tale of Tales operated under a philosophy of radical constraint. They reused their proprietary Drama Princess engine (from 8) for character behavior and the environment renderer from The Endless Forest. They built the entire game in Quest3D, a visual, node-based programming tool that allowed artistically-minded developers to create logic flows without traditional coding. This empowered Harvey to take on the monumental task of modeling all 14 characters and key environments herself after failed attempts to hire a modeler who understood their “creepy-cute,” non-cartoony aesthetic. The post-mortem candidly admits this was “insane” and led to severe crunch (four months of 14-hour days), a trade-off they accepted to preserve their artistic vision over technical polish. Characters clip through trees, animations are simple, and performance is demanding—all direct results of budget and time. Their engine choice also meant a Windows-only release initially, requiring a port to Mac via TransGaming’s Cider technology.

The 2008-2009 Gaming Landscape: The Path arrived as the “indie game” movement was crystallizing. Steam was opening to smaller titles, and games like Braid (2008) and World of Goo (2008) had demonstrated that novel, personal games could find an audience. However, the dominant discourse still firmly categorized games by genre and mechanic. Tale of Tales’ explicit goal was to make a “commercial” art game—to see if a title with minimal traditional gameplay could succeed in the market. Their marketing was a fascinating hybrid of indie hustle and fine-art strategy: an active blog defending their design philosophy, fictional LiveJournals for each of the six sisters to build narrative, and a unique physical release on a black metal USB stick with goodies. They targeted both the gaming press and, quixotically, a “non-gamer” audience, a demographic with little organized infrastructure to discover their title.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Psychology of the Forest

The Plot as Skeleton: The narrative framework is deceptively simple. Six sisters (Robin, 9; Rose, 11; Ginger, 13; Ruby, 15; Carmen, 17; Scarlet, 19) live in a contemporary apartment. Their mother, a voice of societal order, sends each one individually to deliver a basket to a sick grandmother living through a “dark forest.” The explicit instruction is to stay on the path. The core narrative experience is what happens when—as the developers state, “young women are not exactly known for their obedience”—the player chooses to deviate.

Characters as Archetypal Journeys: The sisters are not individuals with detailed backstories but archetypal manifestations of a girl’s psyche at different ages, a point emphasized by their original development names: Kid Red, Innocent Red, Tomboy Red, Goth Red, Sexy Red, Stern Red. Their names reference shades of red (Robin, Rose, Ginger, Ruby, Carmen, Scarlet). Each has a distinct Wolf, an alter-ego or manifestation of her specific desire, fear, or coming-of-age trial:

* Robin (9) meets a literal, hunched wolf in a graveyard—the classic, childhood bogeyman.

* Rose (11) encounters a will-o’-the-wisp over a swamp—a beautiful, elusive promise of flight and dreaminess.

* Ginger (13) is entranced by a Girl in White in a field of flowers, watched by crows—a peer, a feminine ideal, a dangerous friendship.

* Ruby (15) finds a young man at a rusty playground—”Charming,” a first crush