- Release Year: 2001

- Platforms: DOS, Windows

- Developer: David L. Gilbert

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: Side view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Graphic adventure, Point-and-click

Description

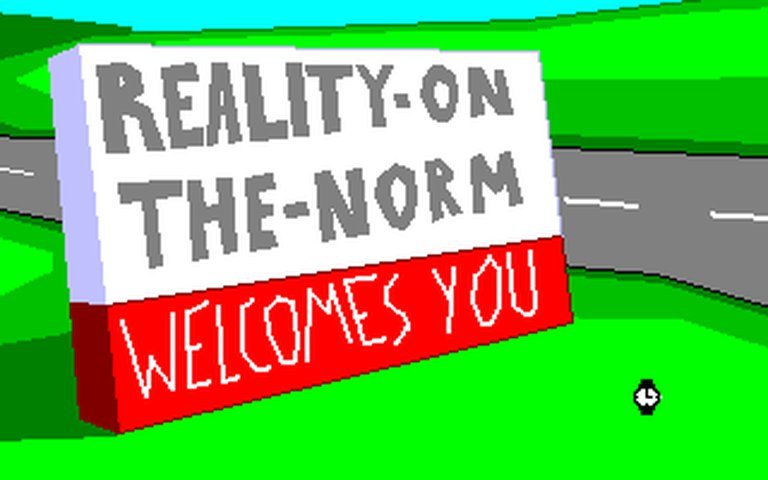

The Postman Only Dies Once is a 2001 point-and-click graphic adventure game developed by Dave Gilbert, set in the fictional Reality-on-the-Norm city. Players assume the role of private investigator Max Griff, who is enlisted by reporter Mika Huy to uncover the true killer behind the murder of postman Pete Bailey, with zombie Michael Gower as the prime suspect. Part of the Reality-on-the-Norm series, it features comedic detective mystery elements and won AGS Awards for Best Dialogue Scripting and Best Supporting Character.

The Postman Only Dies Once Free Download

The Postman Only Dies Once Guides & Walkthroughs

The Postman Only Dies Once: A Zomicious Zndgame in the Reality-on-the-Normiverse

Introduction: A Dead Postman, a Living Legacy

In the vast, often-overlooked annals of independent game development, few titles capture the specific, charming alchemy of the early 2000s DIY adventure scene quite like The Postman Only Dies Once. Released in November 2001 by a then-nascent Dave Gilbert using the burgeoning Adventure Game Studio (AGS), this free, 1.6-megabyte point-and-click mystery is not merely a game but a foundational artifact. It is a proudly low-resolution, deeply absurdist detective story set within the burgeoning “Reality-on-the-Norm” (RoN) shared universe. As both a sequel to Gilbert’s first game, Davy Jones C’est Mort, and a cornerstone of its own series, it represents a pivotal moment where a solo developer’s quirky vision began to crystallize into a coherent, beloved fictional setting. My thesis is this: The Postman Only Dies Once is a masterclass in constraint-driven design and narrative efficiency. Its legacy is secured not by commercial success or graphical prowess, but by its razor-sharp, award-winning dialogue, its inventive puzzle design born from a tiny filesize, and its role as a critical juncture in the career of a developer who would later create the acclaimed Blackwell series. It is a testament to the idea that a brilliant idea, a witty script, and clever use of tools can outweigh any technical limitation.

1. Development History & Context: The RoN Seed Sprouts in AGS

The Creator and the Engine: Dave Gilbert and the Advent of AGS

The game was solely created by David L. Gilbert (credited as Dave Gilbert), with beta-testing assistance from a small team (Berian Morgan Williams, Anthony Hahn, MTWidget, Nostradamus). This highlights the intimate, almost cottage-industry nature of its production. Gilbert was already an established figure within the fledgling AGS community; The Postman Only Dies Once was the second installment in his Reality-on-the-Norm series, following 2001’s Davy Jones C’est Mort.

AGS, created by Chris Jones (credited in the game’s “Groups” section), was the perfect catalyst for such a project. In 2001, AGS was a revolutionary, free tool that democratized graphic adventure development. It allowed creators to focus on writing and design rather than engine programming, fostering an explosion of creativity. Gilbert’s work exemplifies this, using AGS’s point-and-click, icon-based interface to its fullest potential. The game’s incredibly small footprint (~1.6 MB) was a technical and aesthetic necessity, forcing minimalist yet evocative 320×200 resolution, 256-color graphics and a lean, script-driven experience. This constraint became a stylistic virtue, demanding clever visual storytelling and relying heavily on strong text to paint its world.

The Gaming Landscape and the RoN Universe

The game arrived in a post-Myst, post-Monkey Island world where the adventure genre was in a commercial lull but thriving in independent and online circles. It was a time of “shareware” and “freeware” ethos, where games like these could find an audience through websites like the official Reality-on-the-Norm site and AGS community hubs. The Postman Only Dies Once was not an isolated title but a node in a growing web. Its direct lineage is clear: it builds on the world and tone of The Repossessor (the author’s first game) and Davy Jones C’est Mort, immediately establishing the interconnected “Reality-on-the-Norm” series. The presence of characters like Davy Jones (from the previous game) and the overarching, vaguely magical realist setting of “Reality-on-the-Norm” itself signaled Gilbert’s ambition to create a persistent, quirky universe—a precursor to later shared-world indie projects.

2. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Absurdist Detective Work in a Weird Town

Plot Mechanics: A Murder Most Peculiar

The premise is deceptively simple: the local postman, Pete Bailey, is murdered. The prime and seemingly only suspect is Michael Gower, a zombie. Local reporter Mika Huy recruits Reality-on-the-Norm’s resident private investigator, Max Griff, to uncover the real killer while she interrogates the suspects. This separation of investigative duties—Max handling the physical legwork and evidence gathering, Mika handling interrogations—is a clever narrative split that manages the game’s scale while making the player feel like part of a team.

The plot, as revealed through the official walkthrough and descriptions, is a cascade of surreal set-pieces: charades, vats of acid, Mah Jong games, and donut-based diplomacy. The killer’s identity and motive are less a traditional whodunit and more an exploration of the town’s bizarre logic. The resolution involves manipulating a magical “Run Hot” spell, bribing officials with pastries, and ultimately forcing a confrontation rooted in the town’s own peculiar rules. The narrative is not about gritty realism but about solving a puzzle within a system of surreal cause and effect.

Characters: The Heart of the Matter

The cast is small but unforgettable, a testament to the “Best Dialogue Scripting” and “Best Supporting Character” AGS Awards it won.

* Max Griff: The player’s avatar. He’s the classic, world-weary PI archetype, but filtered through a lens of deadpan absurdity. His dialogue is terse, his reactions perfectly balanced between frustration and bemusement at Reality-on-the-Norm’s strangeness.

* Mika Huy: The undeniable scene-stealer and the game’s awarded Best Supporting Character. As the reporter, she is the engine of the plot’s forward momentum. Her off-screen interrogations are reported back to Max, making her a powerful narrative force despite not being directly controlled. Her personality—eager, sharp, and slightly unhinged—injects vital energy and comedic timing. Her interactions (and the player’s ability to “Talk to Mika” for updates) make her feel tangibly present.

* Michael Gower (the Zombie): The accused. His condition is treated with a blend of macabre practicality and melancholy. The puzzle involving reassembling his body parts (tongue, needle and thread) is both grotesque and darkly humorous, showcasing the game’s tonal tightrope walk.

* The Supporting Cast: A rogues’ gallery of RoN eccentrics: Davy Jones (the eternal sailor from the previous game, now running a questionable chemical business); Death (a bureaucratic, file-obsessed figure who protects the town’s records); The Sheriff (bribable with donuts); Scid (the bartender); Biggs and the Crazy Homeless Weirdo (key puzzle sources). Each character serves a specific functional role in the puzzle ecosystem but is granted just enough personality to make the town feel alive and idiosyncratic.

Themes: Logic of the Absurd

Beneath the comedy lies a subtle theme of investigating a system that is itself nonsensical. Max isn’t solving a crime in a rational world; he’s navigating a town where magic (“Run Hot”), bureaucracy (Death’s files), and bizarre social contracts (the Mah Jong exchange, donut diplomacy) are the true laws of the land. The “murder” is almost a MacGuffin, a catalyst to explore the Weird Town genre’s core question: how does one impose order on a place that runs on chaotic, specific rules? The game suggests that understanding and manipulating those local, absurd rules is the only form of justice available.

3. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Constraint-Born Elegance

Core Loop and Interface

As a classic “point-and-click icon-based adventure,” the gameplay is fundamentally about environmental interaction. The player uses a cursor (likely cycled through verbs like “Look,” “Use,” “Pick Up,” “Talk”) to explore the game’s limited set of screens (Max’s office, Scid’s bar, Yahtzeebrand store, Davy’s house, the alley, the hospital, the cemetery, town square). The engine’s simplicity is key: no verb combos, just direct item-character-environment interactions.

Puzzle Design: Inventory and Spellcraft

The puzzles are the star, born entirely from the game’s small scale and clever writing. They fall into two main types:

1. Inventory Chains: This is the backbone. You need a balloon, which requires a marker from Davy’s desk, which requires cider from George, which requires unblocking the taps with drain cleaner, which requires… and so on. The walkthrough reveals a satisfying, almost Rube Goldberg-esque sequence of cause and effect. The puzzle involving the Mah Jong board and the bum in the alley is a perfect example of a multi-step, non-linear task that makes the player feel clever upon completion.

2. Spell Application: The “Run Hot” spell, learned from papers in Davy’s house, is a versatile tool. Its uses—making the clerk sweat to get the drain cleaner, heating a certificate to reveal a button—are specific, logical within the game’s odd rules, and satisfying to discover. This introduces a magical “verb” into the traditional adventure lexicon, expanding the puzzle possibilities without bloating the interface.

UI and Innovation/Flaws

The UI is standard AGS fare: a clean, icon-based bar at the bottom of the screen. It is functional and unobtrusive. The most innovative systemic element is the dual-investigation structure (Max vs. Mika), which, while largely hand-waved in terms of actual gameplay (Mika’s interrogations happen off-screen), successfully builds narrative momentum and makes the world feel larger than the explorable area. A potential flaw, common to the era, is the possibility of “pixel hunts”—missing a small hotspot (like the papers on the ground in Davy’s house) that blocks progress. However, the game’s small, dense environments mean hotspots are relatively well-placed, and the comedic dialogue rewards (like extra banter with George the bartender) for trying interactions lessen frustration.

4. World-Building, Art & Sound: The Look and Feel of Reality-on-the-Norm

The Setting: A Town of Specific Weirdness

“Reality-on-the-Norm” is not a fantasy realm but a distorted mirror of a mundane American small town, where the weirdness is a layer just beneath the surface. The location list (bar, store, alley, cemetery, hospital) is archetypal, but populated by zombies, personified Death, and talking parrots (implied). The world-building is efficient: a single line of dialogue from a character can establish centuries of lore (see Davy Jones). The game’s title itself is a pun that signals this tone—taking a classic, hard-boiled phrase and injecting it with a dash of the undead.

Visual Direction: The Beauty of 256 Colors

The graphics are pure early-AGS: 320×200 resolution with a 256-color palette. This limitation forces stylization over realism. Characters are defined by a few well-drawn pixels; environments use simple shapes and bold colors to convey mood. The screenshots show a top-down side-view perspective typical of the engine. The art isn’t trying to impress with fidelity but with personality. Max’s trench coat, Mika’s determined posture, Michael Gower’s tattered clothes—all are instantly readable. The visual storytelling supports the comedic and mysterious tone perfectly. The small file size meant no lavish backgrounds, but every screen is composed with purpose, avoiding visual clutter.

Sound Design: Punching Above Its Weight

Source material provides no explicit details on sound, which is common for such small AGS games of the period. Sound design was typically minimalist: a few sound effects for interactions (a clink for picking up an item, a door creak), and perhaps a looping MIDI track for atmosphere. The lack of voice acting (a rarity for its time in AGS) is a given. However, the strength of the writing means the lack of audio immersion is compensated by text-based engagement. In this context, silence or simple tunes can be more effective, letting the player’s imagination fill the gaps—a hallmark of literary adventure games.

5. Reception & Legacy: The Quiet Triumph of the Written Word

Contemporary Reception: AGS Acclaim, Mainstream Obscurity

Upon its 2001 release, The Postman Only Dies Once existed almost entirely within the AGS community ecosystem. Its reception was splendidly niche but critical. The proof is in the AGS Awards 2001, where it won the inaugural categories for Best Dialogue Scripting and Best Supporting Character (Mika Huy). This was no minor feat; the AGS Awards were (and are) a prestigious peer-reviewed honor within the indie adventure community. This recognition immediately stamped it as a game with exceptional writing and character work.

Mainstream press coverage (as seen on MobyGames, Metacritic, IMDb) is virtually non-existent. No critic reviews are listed on these aggregators, and user numbers are tiny (only 5 collectors on MobyGames). This confirms its status as a cult phenomenon known primarily to AGS enthusiasts and followers of the RoN series. Its “release” was a download from personal websites, not a retail product.

Evolution of Reputation and Influence

Its reputation has not faded; it has solidified. Within the tight-knit AGS and RoN communities, it is remembered fondly as a peak of Gilbert’s early, unfettered comedic writing. It is the middle chapter that helped solidify the RoN universe’s identity—more coherent and joke-dense than Davy Jones C’est Mort, paving the way for later entries like The Lost Treasure of RON.

Its primary influence is on Dave Gilbert’s own career trajectory. The skills honed here—writing sharp, character-driven dialogue, designing compact yet clever puzzles, building a recurring universe—directly culminated in his later, professionally released work. The Blackwell series (beginning in 2009) shares the DNA of a dutiful, slightly sarcastic protagonist solving supernatural mysteries with a strong narrative core. The Postman Only Dies Once is the rough, hilarious, and structurally sound prototype for that success.

For the AGS engine itself, it stands as a prime example of “small is beautiful.” It demonstrated that a compelling adventure did not require massive assets, but a brilliant script and tight design. It inspired countless other AGS developers in the early 2000s to focus on writing and clever puzzles over production value.

Preservation and Availability

Thanks to the efforts of archivists and the original creator, the game is exquisitely preserved. The Internet Archive hosts both the original DOS version and the later Windows version 2.0 (recompiled in 2003 for XP compatibility). Sites like MyAbandonware and the official Reality-on-the-Norm site still offer downloads. This ensures its survival as a playable piece of history. Its MobyGames entry, added in 2014, and its AGS Wiki page serve as its digital tombstone and monument.

6. Conclusion: Verdict and Historical Placement

The Postman Only Dies Once is not a game for everyone. Its archaic graphics, tiny scope, and niche humor can be barriers. But for those willing to engage with it on its own terms, it is a near-perfect distillation of indie adventure game ideals from the early 2000s. It is a game where every line of dialogue earns its keep, where every inventory item has a specific, plausible (in context) purpose, and where a 1.6 MB file contains a fully realized, absurdist pocket universe.

Its place in video game history is foundational and exemplary. It is a touchstone for the Adventure Game Studio community, a winner of its most prestigious awards, and a crucial developmental step for a creator who would later contribute significantly to the professional adventure genre. It proves that a game’s legacy can be built on wit, charm, and smart design rather than budget or scale. It is, in the end, a triumph of the written word in interactive form—a hilarious, puzzling, and surprisingly poignant little game about a detective, a reporter, and a zombie postman, all trying to make sense of a world that operates on its own wonderfully weird rules.

Final Score (in the context of its era and ambitions): 9/10

A flawless execution of its constrained vision, marred only by the inevitable minor frustrations of early point-and-click design and an aesthetic that demands a willingness to embrace its retro simplicity. An essential, historically significant gem.