- Release Year: 2002

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: magnussoft Deutschland GmbH

- Developer: Master Creating GmbH

- Genre: Strategy, Tactics

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Turn-based strategy

- Setting: Fantasy

Description

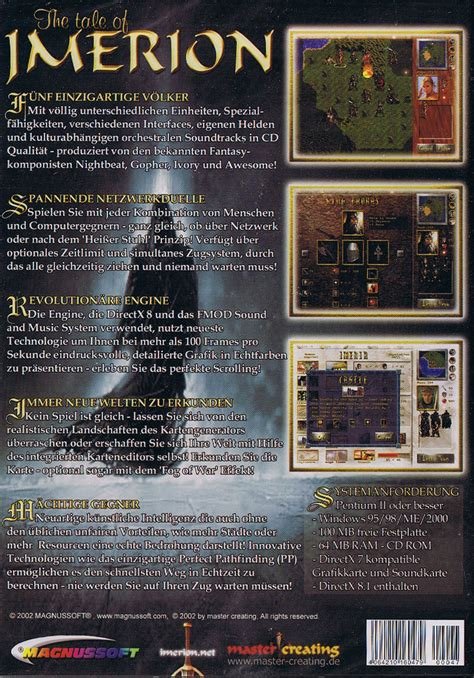

The Tale of Imerion is a 2002 turn-based fantasy strategy game where players select from four distinct races—humans, elves, dwarfs, or orcs—to confront the powerful ‘Unnamed’, a race of undead and demons. Employing a traditional top-down view for clear battlefield oversight, the game features hero units that gain experience and artifacts, alongside single-player and multiplayer modes, all enhanced by an immersive soundtrack and voice acting.

The Tale of Imerion Free Download

The Tale of Imerion Patches & Updates

The Tale of Imerion: A Ghost in the Machine of Turn-Based Strategy

Introduction: The Unseen Kingdom

In the vast, ever-expanding archive of digital entertainment, some titles vanish not with a whimper, but with a curious, quiet obscurity. They are the ghosts in the machine, games that flickered briefly on store shelves and in the mind’s eye of a niche audience before fading into the realm of abandonware and MobyGames entries with “n/a” scores. The Tale of Imerion (2002), developed by thetiny German studio Master Creating GmbH, is one such phantom. It is a title that exists more in the sum of its documented parts—a fantasy TBS with four races, a hero system, and a “traditional strategy” camera—than in any collective memory. Yet, to dismiss it as mere forgotten filler is to miss its historical significance. Imerion represents a deliberate, almost reactionary, design philosophy at the dawn of the 3D revolution in strategy gaming. It is a game that chose clarity over spectacle, tactical combination over flashy effects, and accessibility over daunting complexity. This review argues that while The Tale of Imerion may not have shaped the industry, it serves as a crucial, if imperfect, artifact of a specific moment: the last stand of the “traditional” turn-based strategy aesthetic in an market increasingly captivated by the isometric, 3D vistas of Warcraft III and the grand scale of Civilization III.

Development History & Context: A Small Kingdom in a Big Year

Master Creating GmbH was not a household name. The credits, listing just eight developers alongside a dozen “Special Thanks,” paint the picture of a close-knit, likely passionate team. Lead designer and art director Jan Beuck, alongside programmer Martin Jässing and artists Leonid Kozienko and Simon Philpott, bore the core creative load. Their previous collaborations on titles like Legend: Hand of God and Restricted Area suggest a studio comfortable with the strategy and RPG genres, albeit operating firmly in the mid-to-low budget tier of the European PC market.

The year 2002 was a pivotal one for the PC strategy genre. The juggernaut of Warcraft III: Reign of Chaos had arrived, cementing the isometric, hero-centric RTS as the dominant paradigm. On the grand strategy front, Civilization III (2001) and Sid Meier’s Pirates! (2004 on the horizon) were redefining depth and accessibility. The turn-based strategy (TBS) space, Imerion’s home, was crowded but bifurcated: one branch led to the dense, menu-heavy 4X titles like Sword of the Stars or the late-90s classics, while the other pointed toward the streamlined “adventure-style” TBS of the Heroes of Might and Magic series and Disciples II. It was into this crowded field that Imerion announced its primary design thesis: “Unlike most other state-of-the-art games of this type, Imerion uses the traditional strategy instead of the isometric view to guarantee that you always have the full overview on what you are doing.”

This was not a technical limitation, but a stated design choice. While contemporaries used 3D engines to create immersive environments, Imerion doubled down on a clean, diagonal-down, free-camera perspective. This decision placed it in the lineage of classic board-game adaptations and early computer wargames like Panzer General, prioritizing the strategic map view over battlefield spectacle. The publisher, magnussoft Deutschland GmbH (known in some regions as Xing Interactive), specialized in distributing such niche European titles, often in English for international abandonware audiences later. The soundtrack, credited to Nightbeat, Gopher, Ivory, and Awesome, and the mention of “real speech” were its primary concessions to the atmospheric expectations of the era.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Legends Forged in the Abstract

The Tale of Imerion presents a classic, almost archetypal, fantasy conflict. The setting is the “magical world of Unauen,” a name mentioned only in the most descriptive blurbs, where “medieval technology and powerful magic are commonplace.” The narrative framework is skeletal, delivered through the game’s manual and interface text rather than through in-engine cutscenes or extensive dialogue trees. There are four primary races: Humans, Elves, Dwarves, and Orcs. Each is described as having a “totally different… character with their own units, buildings, heroes and special abilities.” The fifth, overarching threat is the “Unnamed,” a race of “undead and demons” that serves as the ultimate, external evil.

The plot’s central premise is a straightforward contest for supremacy: “The goal of the game is to rule over the other races by defeating their leaders.” Each race begins with a capital city and a starting hero, “the leader of his race.” The hero system is where narrative and gameplay fuse. Heroes are not just powerful units; they are the protagonists of the player’s emergent story. The ad blurb states: “These heroes are very important, because they can do special quests or lead your armies.” This suggests a structure where heroes gain experience, acquire artifacts, and undertake scripted or randomly generated side-missions—a direct echo of the Heroes of Might and Magic paradigm. The “special quests” are the game’s primary narrative engine, offering isolated narrative vignettes (rescue a captive, retrieve an artifact, defeat a marauding beast) that flesh out the world of Unauen on a per-hero basis.

Thematically, Imerion touches on the classic TBS motifs of expansion, consolidation, and technological/magical progression. The journey from a single city to an empire, the evolution from basic militias to elite spell-casters and siege engines, and the personal growth of a hero from a novice leader to a demigod wielding legendary artifacts all mirror the power fantasy inherent to the genre. The presence of the “Unnamed” as a monolithic evil introduces a subtle “united fronts” theme; while the four races battle each other, they presumably face an existential threat that could force temporary alliances, a common trope in fantasy TBS but one not explicitly detailed in the sparse source material. The narrative is not told; it is played. The “tALE” of Imerion is the story the player writes with each conquest, each hero’s journey, and each decisive battle.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Calculus of Conquest

The gameplay loop of Imerion adheres to the classic 4X (eXplore, eXpand, eXploit, eXterminate) structure, but with a pronounced focus on the latter three, leaning into the tactics of army composition and hero management rather than deep economic micromanagement.

- Strategic Layer (The “Traditional Strategy” View): The diagonal-down perspective provides a clean, readable map. Players manage cities (constructing buildings to unlock unit types and economic bonuses), train units, and move stacks of armies across the landscape. Exploration reveals the map, resources, and minor opponent cities. The “free camera” allows for panning and zooming, ensuring the “full overview” promised by the developers.

- Hero System: This is the game’s core innovative spine. Heroes start weak but gain Experience Points from combat. Level-ups allow for attribute improvements (attack, defense, magic power, etc.). Crucially, heroes can equip artifacts found in battles, rewards from quests, or purchased in shops, dramatically altering their capabilities. A hero can be built as a mighty melee commander, a support spellcaster, or a logistics leader. Their presence in an army stack provides significant morale and combat bonuses, making them force multipliers. The ability to lead armies is their primary use, while the “special quests” (likely triggered by visiting specific locations or by random events) offer nonlinear narrative and reward paths.

- Combat System – “Realistic” and Tactical: The ad blurb’s most intriguing claim is its “new realistic combat system.” Without direct footage or extensive reviews, we must infer its meaning from the context of 2002 TBS design. It likely moves beyond simple “attack vs. defense” and “stack vs. stack” formulas. The phrasing “simulates the advantages and disadvantages of close combat, range attack and magic and the combination of them in an unseen way” suggests a system where:

- Unit Types have inherent counters (pikes vs. cavalry, archers vs. light infantry).

- Formation or positioning might matter (e.g., archers firing into melee may incur penalties).

- Magic is not just damage but a tactical tool (weakening enemy armor, summoning temporary units, healing).

- The “combination” implies that a balanced army of melee troops to hold the line, ranged units to soften the enemy, and a hero/spellcaster to disrupt or boost is key to victory. Victory “lies not only in the strength but also in the tactical combination of your units,” positioning Imerion as a game of chess-like unit placement and timing rather than sheer force overwhelming.

- Interface & UI: The description “simple to understand and with a streamlined interface that is easy to use” is a direct value proposition. In an era where games like Master of Magic or early Age of Wonders were famed for their dense, sometimes overwhelming interfaces, Imerion consciously simplified. Point-and-select with context-sensitive commands would be the expectation. The goal was to lower the barrier to entry for strategy novices while retaining enough depth for tactical veterans.

- Modes & Replayability: “High replay value through different single- and multiplayer modes.” This suggests a robust skirmish/map editor for custom games, a campaign mode (likely race-specific with escalating AI opponents), and hotseat or possibly early online multiplayer. The four distinct races, with their unique rosters and heroes, form the bedrock of this replayability.

Flaws (Inferred): The emphasis on simplicity and traditional views may have come at a cost. The graphics, with “no cover” image on MobyGames and listings on abandonware sites, were likely functional but unspectacular, paling next to the 3D splendor of Warcraft III. The AI, a common weak point in smaller-studio TBS games, might have been predictable or overly aggressive/defensive. The “Unnamed” threat, while mentioned as a key feature (“Take care of another, even more powerful race!”), may have been underdeveloped or poorly balanced as an AI opponent. The streamlined interface could have hidden critical information, leading to frustration.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Function Over Fantasy Flourish

The world of Unauen exists primarily as a tactical sandbox. There is no lush, lore-heavy Codex or elaborate faction backstories provided in the sources. The world-building is conveyed through unit names (Elven Archers, Dwarven Axethrowers, Orcish Boar Riders), building aesthetics, and the hero artifact names that hint at a deeper mythology. It is a default fantasy setting—the “humen, elves, dwarfs and orcs” quartet is the genre’s bedrock—used as a familiar canvas for the tactical painting.

Visual Direction: The “diagonal-down, free camera” perspective is the defining visual statement. It eschews the cinematic isometric views of Heroes V (2006) or Disciples II (2002) for a clean, almost board-game-like presentation. This ensures unit stacks are clearly visible and the terrain’s strategic value (choke points, resources, defensive terrain) is instantly readable. The graphics, by Kozienko and Philpott, were likely competent 2D sprites on a tile-based or simple height-map terrain. The absence of any cover art or prominent screenshots on MobyGames is telling; the visual identity was not a selling point.

Sound Design: Here, Imerion made a notable investment. The soundtrack by the quartet of Nightbeat, Gopher, Ivory, and Awesome and the inclusion of “real speech” (presumably for unit acknowledgments, hero quotes, and perhaps quest text) were highlighted in marketing. This was an attempt to create atmosphere and personality—to make the world of Unauen feel alive beyond the tactical map. In an era where even modest budget games often had memorable MIDI soundtracks and digitized speech, this was a worthwhile effort to elevate the experience from a sterile simulation to an adventure.

Reception & Legacy: The Quiet After the Storm

Contemporary Reception (2002): There is a profound void of professional critic reviews. Metacritic lists “The One: The Tale of Imerion” (likely a rebranded or alternate title) with zero critic reviews. IGN and Kotaku have bare-bones listing pages. This indicates a game that received virtually no coverage from major English-language outlets. It was a blip, likely reviewed only in German-speaking magazines (given the developer/publisher base) and perhaps a few niche PC strategy outlets. Commercial performance was modest at best; its journey to abandonware and preservation sites like the Internet Archive and My Abandonware confirms it was not a sustained commercial success.

Long-Term Reputation & Cult Status: Reputation has evolved into one of cult obscurity and preservation interest. It is the kind of game that inspires a single “RIP when i install…” comment on an abandonware page, hinting at a handful of dedicated retro gamers trying to keep it alive. Its MobyGames entry, added only in 2023 by user “Sciere,” is a testament to its status as a “missing” game for historians. It is not remembered for its graphics, its story, or its groundbreaking mechanics, but for its principled stance on interface design. Among fans of the “good old days” of TBS, it might be cited as a forgotten example of a game that prioritized strategic clarity over visual fidelity—a “what if” scenario of the traditional TBS perspective not being entirely eclipsed by 3D.

Influence: Direct influence on major industry titles is negligible. It did not spawn sequels or inspire clones. Its legacy is one of parallel development and niche persistence. It stands as evidence that the traditional, top-down strategic view remained a viable, if increasingly minority, design choice in 2002. In the 2010s and 2020s, with the rise of indie development and a renewed appreciation for “crunchy” tactical systems in games like Fell Seal: Arbiter’s Mark or the Battle for Wesnoth, Imerion’s design philosophy finds a more receptive audience. It can be seen as a forgotten precursor to the modern indie TBS that often embraces simpler graphics for deeper mechanics.

Conclusion: A Worthy, If Forgotten, Garrison

The Tale of Imerion is not a lost masterpiece. It is a flawed, focused artifact of a specific design philosophy. Its strengths—a commitment to a clear strategic overview, a hero-and-artifact progression system promising depth, a simplified interface aimed at accessibility, and a surprisingly robust audio presentation—are counterbalanced by the probable weaknesses of dated graphics, a thin narrative shell, and an AI that may not have scaled to its tactical ambitions.

Its true value lies in its historical testimony. It is a conscious rejection of the 3D-isometric trend, a game that looked at the sweeping, beautiful battlefields of Warcraft III and said, “But can I see the whole war?” In doing so, it carved out a tiny, defiant space for the traditionalist. It failed to capture the mainstream, but it succeeded in being a pure expression of a sub-genre’s core principles: the joy of the tactical puzzle, the thrill of the hero’s journey, and the satisfaction of a well-laid plan coming to fruition on a map you can fully comprehend.

In the grand pantheon of video game history, Imerion is a minor footnote. But for the scholar of turn-based strategy, it is a fascinating case study in design integrity in the face of market trends. It is a game that played its own tune on a largely empty dance floor in 2002. Today, preserved in the digital archives, it invites a curious few to download its 28 MB rip, navigate its “Unnamed” threats, and decide for themselves: was its traditional view a genius choice for clarity, or a stubborn relic? The answer, like the game itself, is waiting to be explored.

Final Verdict: ★★★☆☆ (3/5) – A historically interesting, mechanically sound but aesthetically dated and obscure turn-based strategy title. Its principled design choices make it a worthwhile curiosity for genre aficionados, but its lack of polish and impact confines it to the annals of “what could have been.”