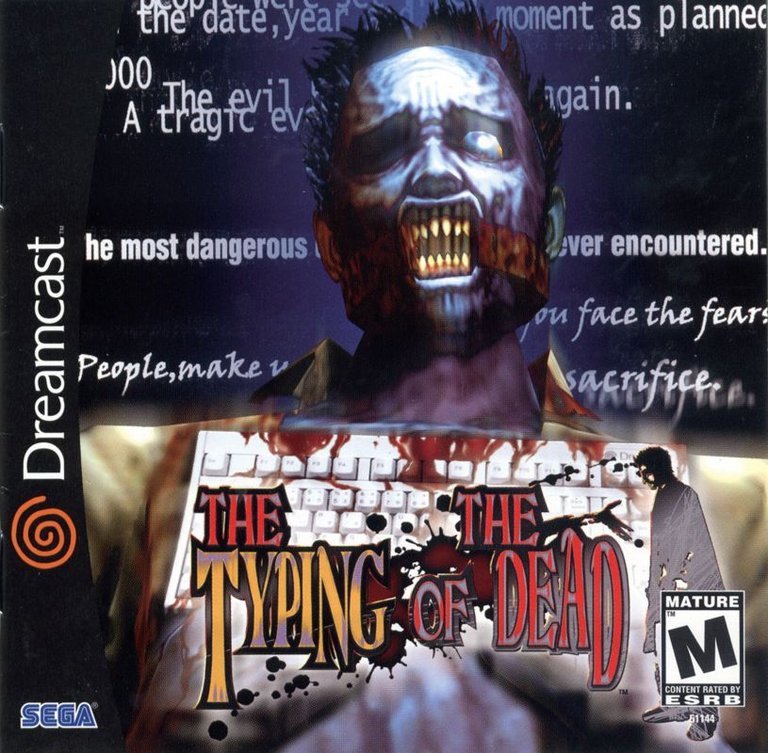

- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Arcade, Dreamcast, Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: Empire Interactive Europe Ltd., SEGA Corporation, SEGA of America, Inc.

- Developer: Smilebit, Wow Entertainment, Inc.

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Co-op, LAN, Single-player

- Gameplay: Rail shooter, Typing

- Setting: Horror, Zombie

- Average Score: 78/100

Description

The Typing of the Dead transforms the arcade light-gun rail-shooter House of the Dead 2 into an innovative edu-tainment typing trainer, where players navigate a zombie-infested, vaguely gothic decaying city armed not with guns but with chest-mounted keyboards. As hordes of undead horrors lunge from the shadows, participants must rapidly type out words displayed on the zombies to dispatch them before they close in, all while racing to save humanity in a narrative-driven journey through eerie urban ruins filled with tutorials and typing challenges to hone skills.

Gameplay Videos

The Typing of the Dead Free Download

Crack, Patches & Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

metacritic.com (83/100): One of the coolest Dreamcast games to date. Excellent challenges, nice visuals, and a surplus of bonus modes are contained within Typing but most of all, Smilebit has given Dreamcast maniacs something truly unique in making typing fun.

ign.com (80/100): You’ll fight through the carpal tunnel that’s sure to arise to get a crack at these zombies.

mobygames.com (71/100): This quirky and clever ‘Port’ is a fun time waster.

maxutmost.com : Someone looked at The House of the Dead 2 and thought, ‘You know what would make this better? A keyboard.’ And they were right.

The Typing of the Dead: Review

Introduction

Imagine a horde of grotesque zombies shambling toward you through the fog-shrouded canals of Venice, their decayed hands clutching not axes or chainsaws, but plungers and spatulas—harmless props in a world where the ultimate weapon isn’t a gun, but your ability to type. This is the absurd genius of The Typing of the Dead (1999), a game that transforms the pulse-pounding light-gun shooter The House of the Dead 2 into an educational typing tutor without sacrificing an ounce of its gory, B-movie charm. Released at the tail end of the arcade era and ported to the Sega Dreamcast and PC, it arrived as the console wars raged and light-gun games like Time Crisis dominated arcades, yet it dared to innovate by strapping keyboards to secret agents battling the undead.

As a game journalist and historian, I’ve chronicled countless titles that blend genres, but few achieve the cult status of this Sega oddity. Its legacy endures not just as a quirky footnote in the House of the Dead series, but as a pioneering example of “edutainment” that makes learning feel like survival horror. My thesis: The Typing of the Dead is a masterful subversion of arcade conventions, proving that humor, horror, and haptic feedback from a keyboard can create one of gaming’s most replayable and influential experiments, even if its brevity and technical limitations hold it back from true greatness.

Development History & Context

The Typing of the Dead emerged from Sega’s innovative arcade division during a transitional period for the company. Developed primarily by WOW Entertainment (a Sega subsidiary known for light-gun shooters) for the NAOMI arcade hardware in 1999, the game was one of the earliest projects from Smilebit, a newly spun-off team of Sega veterans. Producers Shun Arai and Rikiya Nakagawa, alongside director Masamitsu Shiino, envisioned it as a direct riff on The House of the Dead 2 (1998), which had been a massive arcade hit with its on-rails zombie-slaying action. The core challenge: how to port a light-gun game to home consoles without peripheral support, especially after the Dreamcast’s House of the Dead 2 port coincided with the 1999 Columbine tragedy, prompting Sega to remove gun compatibility in North America.

The creators’ vision was boldly educational yet playful—replacing gunfire with typing to leverage the Dreamcast’s optional keyboard peripheral, turning a shooter into a typing trainer. This was no accident; Sega had been experimenting with peripherals since the Saturn era, and the Dreamcast’s VMU and keyboard aimed to differentiate it from Sony’s PlayStation 2. Technological constraints played a key role: NAOMI hardware (essentially a Dreamcast board) allowed seamless arcade-to-console ports, but the PC version (2001, published by Empire Interactive) was locked at 640×480 resolution with software rendering, reflecting early-2000s PC limitations where hardware acceleration wasn’t standardized. No mouse support or adjustable graphics meant a pixelated experience that felt dated even then.

The gaming landscape of 1999-2001 was dominated by survival horror (Resident Evil) and arcade rail shooters (Time Crisis 2), with zombies resurging via Resident Evil clones. Edutainment was stigmatized as “kiddie” fare like Mario Teaches Typing, but Sega’s gamble paid off by injecting gore and humor, appealing to a maturing audience amid the post-Columbine sensitivity around violence. Japanese arcades, with their dual-keyboard cabinets, embraced it as a social novelty, while Western ports targeted niche Dreamcast owners. Budget constraints kept development lean—28 credits, mostly from House of the Dead 2 alumni—focusing on core mechanics over new assets, which preserved the original’s frenetic pace but exposed its arcade roots.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its heart, The Typing of the Dead retells the plot of The House of the Dead 2 with minimal alterations, transplanting players into a zombie apocalypse set on February 26, 2000, in a decaying Venice, Italy. You control AMS (American Military Service) agents James Taylor or Gary Stewart—stoic, trench-coated heroes burdened with chest-mounted keyboards, oversized D-cell batteries, and Dreamcast backpacks—as they investigate an outbreak engineered by the megalomaniacal banker-scientist Caleb Goldman. Goldman, driven by eco-fascist delusions of “restoring balance to the world,” unleashes his bioweapon “Goldman Virus,” mutating civilians into hordes of undead. The narrative unfolds across six chapters: from foggy streets (“A Prelude”) to underground lairs (“Original Sin”), culminating in a rooftop showdown with Goldman’s ultimate creation, the Emperor—a towering, sword-wielding abomination.

Characters are archetypal B-movie fare, amplifying the game’s self-aware camp. James and Gary deliver wooden dialogue like “The city is crawling with the undead… we must hurry!” amid atrocious voice acting that borders on parody—think over-the-top grunts and poorly translated lines like “My foxy wife!” from bosses. Supporting cast includes the enigmatic agent “G” (from the first game), frantic civilians begging for rescue, and Goldman as a mustache-twirling villain monologuing about humanity’s sins. Bosses steal the show: the multi-headed snake Hierophant poses riddles (“What is the capital of France?”), forcing truthful or absurd answers; the gladiator Strength rambles hilariously about his girlfriend or life’s philosophies (“Jack and Jill went up the hill to settle a dispute… Jill got 5 years for assault”); and the Emperor quizzes players on personal ethics, determining one of three endings (explosive suicide, bungee-jump belch, or Superman flight for Goldman).

Thematically, the game explores irony and subversion: typing as empowerment in a powerless world, where words literally kill. It satirizes zombie tropes—undead wielding toilet plungers instead of weapons—while critiquing Goldman’s elitism as a metaphor for unchecked corporate hubris (echoing Y2K fears). Dialogue’s cheesiness underscores themes of communication’s power; typos lead to “death” (screen blood splatters), mirroring how miscommunication dooms society. Endings vary by input honesty, adding replayability and philosophical bite: truthful answers yield grim realism, lies absurd escapism. Though the narrative is linear and unoriginal, its delivery—punctuated by zombie moans and typing gunshots—elevates it to comedic horror gold, making themes of survival through literacy unexpectedly profound.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

The Typing of the Dead deconstructs House of the Dead 2‘s rail-shooter loop into a typing gauntlet, where progression hinges on keystroke accuracy rather than aim. Core gameplay unfolds in first-person, on-rails sequences: zombies lunge from alleys or canals, each emblazoned with words or phrases (e.g., “zombie” early on, escalating to “unisex codpiece” or full sentences later). Type correctly to “shoot” (a satisfying gunshot sound per key), depleting health; errors trigger a miss whistle and vulnerability. Speed and precision determine survival—slow typists die quickly, as enemies close in for graphic (green-goo) finishes like axe-thwacks or bites.

Combat innovates brilliantly: no gunplay means pure cognitive pressure, with phrases randomizing for replayability. Boss fights twist mechanics—riddles require correct answers amid distractions, while Strength demands typing his rambling monologues. Inventory system in “Original” mode (vs. pure-scoring “Arcade” mode) lets players stock up to five items (Molotov cocktails, zombie tranquilizers) rescued civilians provide, activated via hotkeys for crowd control. Branching paths emerge from hostage rescues, altering routes (e.g., saving a family unlocks a sewer detour), adding light choice without derailing the linear structure.

Character progression is typing-focused: Tutorials teach touch-typing basics, Drills offer themed exercises (e.g., flower names), and Boss mode isolates encounters for practice. Difficulty scales across modes—Easy shortens phrases, Hard ramps complexity and speed—unlocking bonuses like extra lives or pre-loaded items via coin challenges (type-kill quotas in timed arenas). UI is minimalist: a health bar, typing prompt box, and score counter dominate the screen, with keyboard layouts optionally displayed for novices. Multiplayer shines in arcade (dual keyboards) or PC network mode (two PCs), fostering competitive typing duels, though setup is cumbersome (no local co-op without mods).

Flaws abound: the game’s arcade brevity (1-1.5 hours) feels insulting for $20-50 retail, lacking HOTD1 content or expansions. No adjustable graphics or quit option (Ctrl+Alt+Del required) frustrates modern play, and blood requires file tweaks for full gore. Yet innovations like haptic typing feedback and randomized phrases make it addictive—typos feel punishingly real, turning education into tension. It’s a flawed loop, but one that masterfully gamifies typing, far surpassing dry tutors like Mavis Beacon.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The Typing of the Dead inherits House of the Dead 2‘s gothic Venice as its canvas—a labyrinth of crumbling palazzos, mist-veiled bridges, and blood-slicked piazzas overrun by zombies. World-building is atmospheric but sparse: the city feels alive with peril, from groaning hordes in opera houses to subterranean labs pulsing with bioluminescent horror. Rescues humanize the decay—cowering families plead “Help me!”—contrasting Goldman’s sterile empire, symbolizing civilization’s fragility. Branching paths enhance immersion, like gondola chases or labyrinthine boss arenas, but it’s all backdrop to typing frenzy; exploration is impossible, keeping focus on survival.

Visual direction is a mixed bag, faithfully replicating NAOMI-era 3D polygons: zombies boast detailed rot (bulging eyes, tattered flesh), exploding in green sludge (or red blood via mods), but low-res textures and jittery animations scream 1998 arcade. Dreamcast ports shine with vibrant lighting—neon-lit streets glow eerily—but PC versions suffer pixelation and fixed low-res, looking archaic by 2001 standards. No updates mean aliasing and pop-in persist, yet the absurdity elevates it: agents’ keyboard rigs and plunger-wielding foes add visual humor, contributing to a cartoonish horror vibe that softens the M-rated gore.

Sound design amplifies the chaos: each correct keystroke erupts in a shotgun blast, errors elicit limp whistles, building rhythmic tension like a deranged typewriter symphony. Zombie moans, glass shatters, and civilian screams create a claustrophobic soundscape, punctuated by Tetsuya Kawauchi’s pulsing synth score—ominous drones swelling to frantic beats during rushes. Voice acting is infamously hammy (“I kick ass for the undead!”), turning camp into asset; boss rants like the gladiator’s anecdotes induce laughter amid dread. Overall, these elements forge an experience that’s viscerally engaging, where audio cues make typing feel weaponized, enhancing the theme of words as violence in a world of decay.

Reception & Legacy

Upon arcade launch in Japan (1999), The Typing of the Dead ranked fourth in dedicated arcade earnings per Game Machine, proving its novelty drew crowds to dual-keyboard cabinets. The Dreamcast port (2000 JP, 2001 NA) earned “favorable” Metacritic scores (83/100), with IGN (9/10) hailing it as “one of the coolest Dreamcast games” for making typing “fun,” and GameSpot (8.7/10) praising its replay value. Critics lauded the humor—phrases like “brain douche” and poor VO as “comedy gold”—and educational hook, though some (PC Gamer, 69%) decried repetition and dated visuals. PC version (2001) scored 75/100, with GameZone (8/10) calling it “awesome” for $20 value, but Eurogamer noted network co-op hassles. Mixed voices emerged: PC World listed it among “worst games” for its premise, while Video Games (Germany) scored it 30/100 for lacking “Spielspaß” (fun).

Commercially, it was a modest success: PC sales hit 120,000 units by 2003, bolstered by budget pricing and GameTap availability (2007). Reputation evolved from gimmick to cult classic—Game Informer named it gaming’s “weirdest” title (2008), and it’s cited in “1001 Video Games You Must Play Before You Die.” Influence ripples through edutainment: sequels like Typing of the Dead 2 (2007) and Overkill (2013) expanded the formula, while English of the Dead (DS, 2008) targeted language learning. It inspired crossovers like The Tempura of the Dead and proved peripherals viable, paving for Kinect/Wii motion controls. In zombie-saturated media, it stands as a quirky antidote to grimdark tropes, influencing games like Typing of the Dead: Zombie Panic (PS2, 2004) with minigames. Today, it’s emulatable abandonware, cherished for subverting shooters into skill-builders.

Conclusion

The Typing of the Dead is a riotous anomaly: a typing tutor wrapped in zombie viscera, where keystrokes dispatch the undead with more flair than any light gun. Its strengths—hilarious dialogue, tense mechanics, and innovative edutainment—outweigh flaws like brevity and technical datedness, creating a replayable gem that teaches without preaching. Development ingenuity, thematic irony, and atmospheric craft cement its place as a bold experiment in the House of the Dead saga and arcade history. Verdict: Essential for genre historians and typists alike, it’s a 9/10 cult masterpiece that reminds us gaming’s power lies in unexpected fusions—type or die, indeed. If you’re emulating or hunting a Dreamcast keyboard, dive in; it’s the weirdest way to level up your WPM.