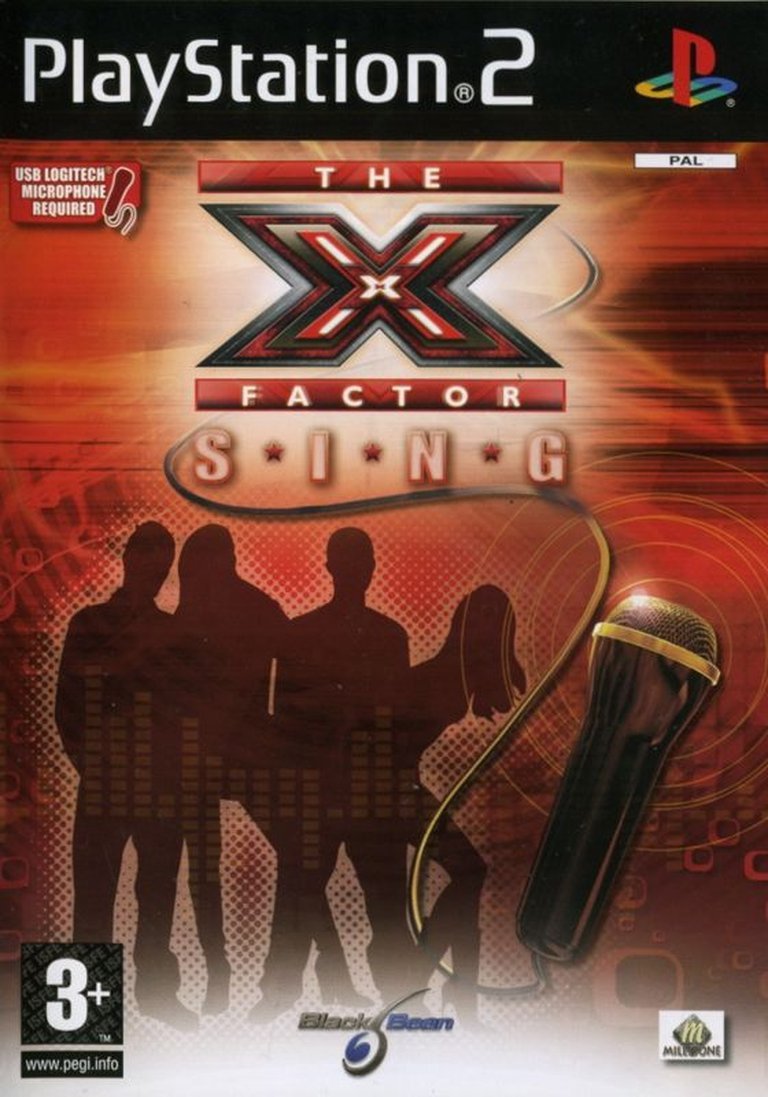

- Release Year: 2005

- Platforms: PlayStation 2, Windows

- Publisher: Lago S.r.l.

- Developer: Milestone s.r.l.

- Genre: Action, Simulation

- Perspective: Third-person

- Game Mode: Hotseat, Single-player

- Gameplay: Game show, Mini-games, Music, quiz, rhythm, trivia

- Setting: Game show

- Average Score: 38/100

Description

The X Factor Sing is a karaoke-style singing game where players belt out tunes with on-screen lyrics and pitch guidance. Immerse yourself in the TV show experience with judge comments and special performances. Party modes add fun mini-games, and the bundled USB microphone makes it ready to play. Features a variety of tracks and supports up to 8 players.

The X Factor Sing Reviews & Reception

empireonline.com : Sadly, the game is a shambles.

eurogamer.net : The game just ends up feeling like a cynical cash-in.

The X Factor Sing: Review

Introduction

In the mid-2000s, The X Factor redefined television talent shows, blending raw vocal performances with dramatic judge commentary to create a global phenomenon. Naturally, a video game adaptation seemed inevitable—a chance to bring the high-stakes auditions and live finals into players’ living rooms. Yet, The X Factor Sing, released on October 21, 2005, for Windows and PlayStation 2, stands as a cautionary tale of licensing potential squandered by rushed development and design flaws. Bundled with a USB microphone, this karaoke rhythm game promised an authentic X Factor experience but instead delivered a hollow, repetitive slog that failed to capture the show’s magic or the genre’s evolving standards. This review dissects why The X Factor Sing fell short, examining its context, mechanics, and legacy within the 2005 gaming landscape.

Development History & Context

Developed by Milestone s.r.l.—an Italian studio primarily known for racing titles like Corvette Evolution GT and Alfa Romeo Racing Italiano—and published by Lago S.r.l. (later Black Bean Games), The X Factor Sing capitalized on the show’s peak popularity. The game’s 94-credit roster suggests a substantial team effort, but Milestone’s pedigree in action-simulation games rather than music or TV licenses hints at a mismatched expertise. Technologically, the game required a USB microphone to function, with the PC version criticized for its “fiddly” interface that couldn’t match console playability around a television. Released in Europe during a pivotal year for gaming—the same month as Resident Evil 4’s PS2 debut and the Xbox 360’s launch—The X Factor Sing arrived amid a surge in rhythm games. Guitar Hero had just debuted, and Sony’s SingStar dominated the karaoke market. However, the game missed key trends: the seventh console generation was dawning, portable gaming was booming (thanks to the Nintendo DS and PSP), and licensed titles were increasingly scrutinized for quality. Milestone’s focus on technical execution over innovation resulted in a product that felt dated before launch, lacking the polish of contemporaries like Karaoke Stage.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

While the X Factor TV show thrives on narrative arcs—from hopeful auditions to live finals—The X Factor Sing jettisons this core structure. The game’s “story” is a shallow imitation: players perform in “Audition” or “Live Challenge” modes without progressing through the show’s iconic stages. Thematic dissonance is immediate; Sharon Osbourne’s absence due to licensing issues (replaced by voice-only Simon Cowell and Louis Walsh) robs the game of its most beloved judge dynamic. Their comments—repetitive, one-liners like “I’d have to say yes” or “You’re really good”—are delivered over static photos, not video clips, destroying the X Factor‘s signature theatricality. The game attempts to reward progress with unlockable “extras” (full-length videos of past X Factor performances), but these feel like afterthoughts rather than narrative payoffs. There’s no career mode, no contestant rivalries, and no sense of journey—just isolated performances. This thematic flatness extends to the game’s presentation; a generic red background with swirling white elements replaces the show’s vibrant sets, making players feel like they’re trapped in a karaoke purgatory rather than a star-making stage.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

At its core, The X Factor Sing employs a straightforward pitch-matching mechanic: lyrics appear on-screen with visual pitch indicators, and players must sing in tune to score points. Theoretically simple, the execution is deeply flawed. The game’s scoring system is inconsistent, punishing minor pitch deviations while rewarding robotic accuracy over emotional delivery. Modes are limited: “Audition” for solo players and “Live Challenge” for teams of up to eight, but no duets are possible due to the single bundled microphone. Party modes introduce baffling mini-games like “Sing for Banana” (where bars become bananas) or “Serenade” (with love-hearts), but these are lazy reskins of the core gameplay. The “A Capella Challenge” (where backing tracks drop out) is the only novel element, yet it’s overshadowed by the game’s technical shortcomings. The microphone detection is unreliable, and the PC version’s interface is “cumbersome,” as noted by PC Zone. Progression is arbitrary—unlocking videos requires near-perfect scores—but there’s no autosave, risking lost progress. Ultimately, the gameplay loop is monotonous: sing poorly, get generic praise; sing well, unlock content. It lacks the addictive challenge of Guitar Hero or the communal fun of SingStar.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The X Factor Sing‘s world-building is a study in missed opportunities. The game attempts to evoke the TV show’s atmosphere but fails at every turn. Visually, it’s barren: a static red background with floating white objects never changes, regardless of song or performance. Judges are represented by two static photos each, eliminating the dynamic reactions that define the X Factor. Even the tracklist—while featuring original master tracks by artists like U2 (“Beautiful Day”), Duran Duran (“Rio”), and Tony Christie (“Is This the Way to Amarillo”)—is a mishmash of dated hits (“Oops!… I Did It Again” by Britney Spears) and forgotten pop (Samantha Mumba’s “Gotta Tell You”). Critically, Eurogamer lamented the “poor song selection,” deriding artists like Ronan Keating and The Lighthouse Family as “Magic FM favourites circa 2003.” The judges’ voice-overs are equally uninspired—short, repetitive, and lacking the bite of Cowell’s real-world critiques. Sound design is the lone bright spot: original tracks ensure authentic audio, but the presentation undermines this. With no music videos or dynamic visuals, the game feels like a karaoke app stripped of personality, not a celebration of musical talent.

Reception & Legacy

The X Factor Sing was met with near-universal derision, reflecting in its abysmal critical scores. On Metacritic, it holds a 38% average based on two reviews: PC Zone awarded it 45% (calling the PC version “too fiddly” and recommending console alternatives), while Eurogamer savaged the PS2 version with a 30%, declaring it “a game that will disappoint both karaoke fans and those who love the TV show.” Player scores on MobyGames are equally damning at 1.9/5. Common complaints included the “shoddy presentation,” “lack of gameplay options,” and “poor song selection.” Empire Online mocked the game as a “cynical cash-in,” while PC Zone noted it was “better off getting one of the decent versions—SingStar or Karaoke Stage.” Commercially, the game faded into obscurity; VGChartz lists no sales data, and its PAL-only release (including the UK, France, and Germany) limited its reach. Legacy-wise, The X Factor Sing is a relic of an era when licensed games were rushed to market without innovation. It didn’t influence future karaoke titles, which instead refined mechanics (e.g., SingStar‘s track libraries) or embraced new hardware (the 2010 X Factor game used motion controls). Milestone s.r.l. continued racing games, and the title remains a footnote in both the X Factor franchise and rhythm gaming history—remembered only for what it could have been.

Conclusion

The X Factor Sing epitomizes the perils of licensed game development: a promising concept undermined by technical mediocrity, design apathy, and a failure to understand its source material. Despite its bundled microphone and original tracks, the game offers a hollow experience—stripped of the X Factor‘s drama, judges’ personalities, and narrative progression. Its limited modes, repetitive mini-games, and dated song selection rendered it obsolete even in 2005, overshadowed by superior alternatives like SingStar. While it technically fulfills the bare minimum of a karaoke game—pitch detection and scoring—its lack of innovation and polish relegate it to the bargain bin of history. For all its potential, The X Factor Sing is not just a bad game; it’s a missed opportunity, a cautionary tale that underscores how licensing alone cannot salvage a product devoid of passion or vision. In the pantheon of rhythm games, it is a forgotten star, extinguished long before its time.