- Release Year: 2013

- Platforms: Windows

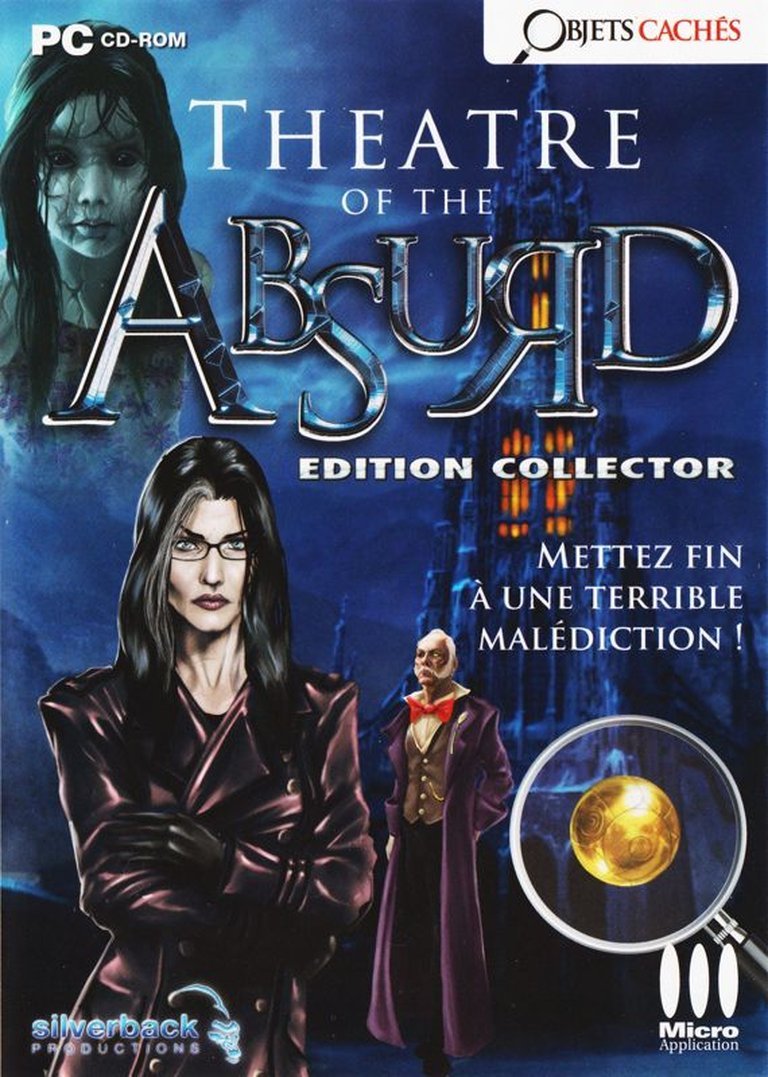

- Publisher: Game Agents Corporation, Micro Application, S.A.

- Developer: Gogii Games Corp., Silverback Productions

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: First-person

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Hidden object, Mini-games, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Europe

Description

Theatre of the Absurd (Collector’s Edition) is a first-person horror adventure game set in Europe, featuring a female protagonist who navigates eerie environments to confront a nightmarish mystery. Players engage in hidden object searches, solve intricate puzzles and mini-games, with the Collector’s Edition enhancing the experience through an included strategy guide and an additional exclusive chapter.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Get Theatre of the Absurd (Collector’s Edition)

Guides & Walkthroughs

Theatre of the Absurd (Collector’s Edition): Review

Introduction

In the shadowy underbelly of early 2010s casual gaming, where hidden object adventures whispered tales of mystery and dread, Theatre of the Absurd (Collector’s Edition) emerges as a haunting artifact—a digital diorama of existential terror wrapped in the familiar trappings of point-and-click puzzles. Released in 2013 for Windows, this game from developers Silverback Games and Gogii Games Corp. draws players into a first-person horror narrative set against a European backdrop, blending hidden object hunts with mini-games and puzzle elements to explore themes of isolation and the uncanny. As a game historian, I’ve pored over its sparse but evocative legacy on platforms like MobyGames, where it stands as an underdocumented gem collected by only a handful of enthusiasts. My thesis: While Theatre of the Absurd may not revolutionize the genre, its Collector’s Edition elevates a solid hidden object experience into a collector’s curiosity, preserving a snapshot of mid-2010s indie horror adventures that prioritized atmospheric immersion over blockbuster spectacle.

Development History & Context

The creation of Theatre of the Absurd (Collector’s Edition) reflects the burgeoning indie scene of the early 2010s, a time when casual games were exploding in popularity thanks to digital distribution platforms like Big Fish Games and Steam, yet still tethered to physical CD-ROM releases for broader accessibility. Developed by Silverback Games—a lesser-known studio likely focused on niche adventure titles—and Gogii Games Corp., a Canadian developer renowned for producing accessible hidden object and puzzle games for the casual market, the title was published by Game Agents Corporation and Micro Application, S.A., the latter a French company specializing in localized software for European audiences. This multinational collaboration underscores the era’s gaming landscape, where small teams outsourced development to capitalize on the hidden object genre’s low-barrier entry, appealing to players seeking bite-sized escapism amid the rise of mobile gaming.

Technological constraints played a pivotal role: Released in 2013, the game ran on standard Windows hardware without the demands of modern 3D engines, relying instead on pre-rendered backgrounds and simple scripting for its first-person perspective. This was the tail end of the Flash-era casual boom, before Unity and Unreal Engine democratized development, but after the 2008 financial crisis had shifted focus toward affordable, single-player experiences. The gaming landscape at the time was dominated by AAA titles like The Last of Us and mobile hits like Candy Crush, leaving room for horror-infused adventures like this one to thrive in budget markets. Gogii Games, in particular, envisioned a blend of psychological horror with accessible puzzles, drawing from influences such as the surreal works of playwrights like Samuel Beckett—evident in the title’s nod to “Theatre of the Absurd”—to infuse mundane object-hunting with existential unease. The Collector’s Edition, featuring an extra chapter and strategy guide (noted as a physical hint book in MobyGames groupings), was a savvy business model choice, catering to completionists in an era when deluxe editions helped extend the lifecycle of casual releases.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

At its core, Theatre of the Absurd unfolds as a first-person horror tale centered on a female protagonist thrust into a nightmarish European labyrinth, where reality frays at the edges like a poorly stitched costume. The plot, as pieced together from the game’s MobyGames description and genre conventions, revolves around a descent into surreal dread: the protagonist, a lone woman navigating decaying theaters and shadowed streets, uncovers fragments of a demonic cube—a Japanese-localized spelling hints at “悪魔のキューブ” (Devil’s Cube)—that warps her perception of the world. This extra chapter in the Collector’s Edition extends the base narrative, delving deeper into the cube’s origins, perhaps revealing it as a metaphysical artifact summoning absurd horrors inspired by existentialist literature.

Characters are sparse but archetypal, with the female lead embodying vulnerability and resilience; her internal monologues, delivered through ambient narration, probe themes of isolation and the absurdity of existence. Dialogue is minimalistic—whispers from ghostly apparitions or cryptic notes scattered in hidden object scenes—serving not to drive exposition but to amplify unease. No ensemble cast dominates; instead, the narrative pivots on environmental storytelling, where everyday objects morph into symbols of psychological fracture. Thematically, the game excavates the “absurd” as coined by Camus and Sartre: the protagonist’s futile quests mirror life’s meaninglessness, with horror elements—eerie shadows, impossible geometries—manifesting as manifestations of existential void. Set in a vaguely European milieu (cobblestone alleys evoking Paris or Prague), it critiques modernity’s alienation, using the theater motif to stage life’s performance as a tragic farce. This depth elevates it beyond rote puzzles, transforming hunts for items into metaphors for piecing together a shattered psyche, though the lack of voice acting (inferred from the era’s tech) leaves some emotional beats feeling distant.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Theatre of the Absurd adheres faithfully to the hidden object adventure blueprint, constructing core loops around exploration, item collection, and puzzle-solving in a first-person view that immerses players without overwhelming controls. The primary mechanic is the hidden object scene: cluttered environments challenge players to spot and interact with obscured items, often morphing into inventory-based puzzles where collected tools unlock doors or disarm traps. This loop is iterative—progress through chapters by alternating between object hunts (for narrative clues) and mini-games, which add variety through simple mechanics like pattern-matching or logic grids, evoking the tactile satisfaction of 1990s point-and-clicks but streamlined for casual play.

Combat is absent, true to the genre, but tension builds through timed puzzles that simulate peril, such as evading spectral pursuers by solving riddles under pressure. Character progression is light: the protagonist gains no RPG stats, but inventory management evolves, with items combining in intuitive ways to reveal story branches. Innovative systems include the “absurd” twists—objects that defy logic, like a key hidden in a dreamlike illusion—flipping expectations and rewarding observation. Flaws emerge in the UI: the first-person interface, while atmospheric, can feel clunky on older hardware, with cursor sensitivity issues and occasional pixel-hunting frustration in dimly lit scenes. Mini-games provide relief, ranging from jigsaw assembly (reconstructing memory fragments) to cipher-breaking (decoding cube inscriptions), but repetition creeps in across the base game’s three chapters, mitigated somewhat by the Collector’s Edition’s extra content. Overall, the systems prioritize accessibility—one-player, offline mode on CD-ROM—making it a gateway for horror novices, though purists might decry the lack of branching narratives or deeper customization.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The game’s European setting crafts a claustrophobic world of faded grandeur: crumbling theaters with velvet curtains torn by time, fog-shrouded streets lined with gas lamps, and interiors blending Gothic spires with modernist decay. This “Theatre of the Absurd” isn’t a bustling continent but a subjective hellscape, where locations loop surrealistically—the extra chapter perhaps venturing into a liminal backstage realm. World-building shines through environmental details: posters of forgotten plays hint at the protagonist’s backstory, while the demonic cube serves as a MacGuffin warping spaces into Escher-like paradoxes, contributing to a cohesive atmosphere of disorientation.

Visually, the art direction employs hand-painted 2D backdrops in muted palettes—grays, deep crimsons, and sickly greens—to evoke 19th-century Expressionism, with first-person framing enhancing immersion like peering through a proscenium arch. Hidden objects are cleverly integrated, blending into the scenery without garish highlights, though screenshots (as archived on Internet Archive) suggest a polished yet dated style, reminiscent of Big Fish Games’ output. Sound design amplifies the dread: a sparse orchestral score swells with dissonant strings during puzzles, punctuated by creaking floorboards, distant echoes, and subtle whispers that blur diegetic and ambient layers. No full voiceover, but sound effects—clinking glass, rustling fabrics—forge an auditory theater, heightening isolation. These elements synergize to create an experience that’s more mood piece than spectacle, immersing players in a tangible yet intangible Europe where every shadow whispers absurdity.

Reception & Legacy

Upon its 2013 launch, Theatre of the Absurd (Collector’s Edition) flew under the radar, with MobyGames reporting no critic reviews and zero player ratings—a Moby Score of n/a underscoring its commercial obscurity. Publishers targeted niche casual markets via CD-ROM and digital portals, achieving modest sales among hidden object fans but lacking the buzz of contemporaries like Mystery Case Files. Collected by just four players on MobyGames (as of last modification in January 2024), it suggests limited mainstream traction, perhaps due to its horror leanings clashing with the genre’s lighter fare. European localization (e.g., French and Spanish editions) may have boosted regional appeal, but globally, it was overshadowed by free-to-play mobile shifts.

Over time, its reputation has evolved into cult curiosity, preserved on archives like Internet Archive where the 179.7MB download invites retro exploration. Influence is subtle: it echoes in later Gogii titles and hidden object horrors like Brink of Consciousness (related on MobyGames), popularizing female-led narratives in casual games. Industry-wide, it exemplifies the 2010s “collector’s edition” trend—bonus chapters and hint books as value-adds—paving the way for deluxe models in indie adventures. Not a genre innovator like The 7th Guest, it nonetheless contributes to the hidden object canon, influencing preservation efforts by highlighting overlooked titles. In video game history, it occupies a footnote: a testament to small studios’ ambition amid digital democratization.

Conclusion

Theatre of the Absurd (Collector’s Edition) distills the essence of early 2010s casual horror into a compact, atmospheric package—its first-person puzzles and surreal European nightmare weaving a narrative tapestry that’s intellectually provocative yet accessibly playful. Drawing from sparse but telling sources like MobyGames’ specs and archival echoes, the game reveals a vision constrained by era and budget but rich in thematic ambition, from existential dread to innovative object-hunting twists. Flaws in UI repetition aside, the extra content elevates it for enthusiasts. Ultimately, it earns a solid place in video game history as an underappreciated bridge between literary absurdism and digital escapism—a collector’s edition worthy of rediscovery in the annals of indie adventures. Verdict: 7.5/10—hauntingly niche, eternally obscure.