- Release Year: 2000

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Crystal Interactive Software, Inc., Cyberium Multi Media B.V., Musicbank Ltd.

- Developer: Full Home Studios

- Genre: Puzzle, Sliding block, Tile puzzle

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Jigsaw puzzles, Memory, Skill system, Sliding block

Description

Theme Puzzle is a memory and skill-based puzzle game released in 2000 for Windows. Players choose from themes like animals, sports, travels, or scenic views, and then solve puzzles created from square-cut stills of these images. The game features three distinct modes: ‘Compo’, where players assemble pieces like a jigsaw puzzle without rotation; ‘Chrono’, a timed sliding-tile puzzle; and ‘Arcade’, an untimed version of the sliding puzzle.

Theme Puzzle Free Download

Crack, Patches & Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Theme Puzzle: A Forgotten Curio in the Digital Puzzle Box

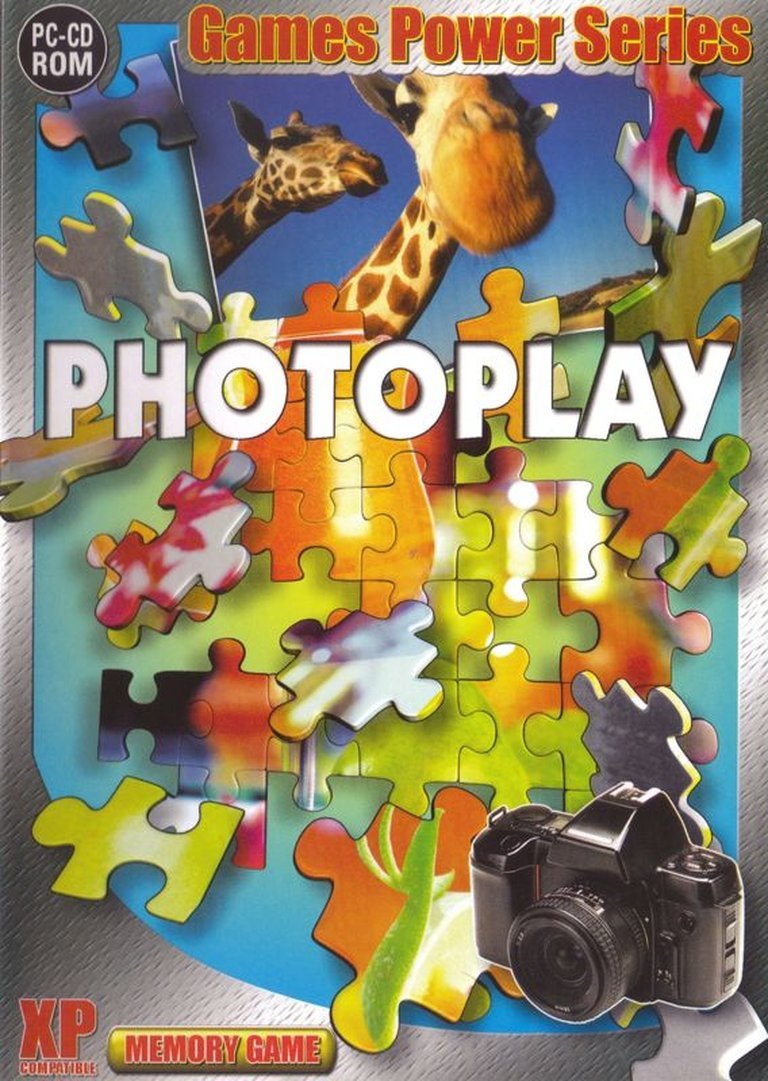

In the vast and often uncurated archive of video game history, there exist titles that are not so much forgotten as they are never truly known. They are the phantoms of software catalogs, released into a crowded market with little fanfare, only to retreat into the obscurity of abandonware sites and eBay listings. Theme Puzzle, also known under the enigmatic alias Photoplay, is one such artifact. Developed by the scarcely-documented Full Home Studios and released at the dawn of the new millennium, it represents a fascinating, if flawed, time capsule of a specific moment in PC gaming—when budget CD-ROM titles filled software racks, aiming to capture casual interest with simple, accessible concepts. This review will unearth and examine this digital relic, arguing that while Theme Puzzle is mechanically unambitious and critically overlooked, it serves as a perfect case study of the pragmatic, low-risk development that flourished on the periphery of the industry.

Development History & Context

The Studio and The Vision

Full Home Studios is a name that echoes only faintly through the annals of MobyGames. The credits for Theme Puzzle list a skeleton crew of primarily two individuals: Antonio Arteaga, who handled programming and music, and José Carlos Garcia, responsible for design and graphics. A third entity, “Zero WarningsStatos Associated Developpers,” is thanked, hinting at a possible collaborative or support network, but the details are lost to time. This two-person operation epitomizes the small-scale, entrepreneurial spirit of late-90s/early-2000s PC development. Their vision was not to revolutionize the genre but to capitalize on a proven, evergreen formula: the jigsaw puzzle.

The gaming landscape of 2000 was one of extreme dichotomy. On one end, blockbuster 3D accelerators were pushing titles like Deus Ex and The Sims into the mainstream. On the other, the market was still saturated with affordable, casual-focused titles sold in jewel cases at big-box stores. Theme Puzzle was squarely aimed at the latter audience—a demographic seeking undemanding, familiar entertainment, perhaps parents looking for a safe diversion for their children or retirees wanting a digital pastime.

Technological Constraints and The CD-ROM Era

The technical specifications for Theme Puzzle are a snapshot of its era. A 60 MB install size, distributed on CD-ROM, and compatible with Windows 95/98/Me/2000. This was a period of transition; Windows XP was on the horizon, but many home PCs were still running on older operating systems. The game’s minimal system requirements were its greatest asset, ensuring it could run on virtually any home computer of the day. The design reflects these constraints: static 2D images, a simple GUI, and a complete lack of any complex animations or 3D rendering. It was built for functionality and accessibility, not graphical prowess.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive

To analyze Theme Puzzle for its narrative or character depth would be to critique a hammer for its inability to screw in a bolt. This is a game entirely devoid of narrative, and its “themes” are purely aesthetic classifications. The player selects from four categories: Animals, Sports, Travels, and “Scenics” (landscapes). These are not story beats but visual folders.

However, one can perform a thematic reading of its intent. The very act of categorizing puzzles into these wholesome, universally agreeable topics is telling. It speaks to a design philosophy aimed at creating a neutral, inoffensive, and comforting experience. The “theme” is not a narrative but a mood—one of pleasant nostalgia, a virtual replacement for the physical jigsaw puzzle box pulled out on a rainy afternoon. The alternate title, Photoplay, subtly reinforces this idea. It’s not about grand drama; it’s about the playful manipulation of familiar, photographic imagery. The “story” is the quiet, personal satisfaction of restoring order to fragmented chaos.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems

Theme Puzzle offers three distinct modes, presenting two classic puzzle types with slight variations.

-

Compo Mode: This is the standard jigsaw puzzle implementation. A chosen image is divided into large, square pieces that the player must drag and place into the correct position on a grid. The key differentiator here, as noted in the description, is the absence of rotation or mirroring. This simplification significantly lowers the cognitive difficulty and skill ceiling, making it a pure test of spatial recognition rather than manipulation. It’s a design choice that firmly cements its status as a casual, entry-level experience.

-

Arcade Mode & Chrono Mode: These two modes shift the gameplay from jigsaw logic to that of a sliding tile puzzle, specifically evoking the classic “15-puzzle” (here implied as a “9-puzzle”). The player must slide scrambled square tiles within a grid to reassemble the image. The mechanical difference between these two modes is razor-thin:

- Arcade Mode is untimed, allowing for leisurely solution.

- Chrono Mode introduces a timer, adding a layer of pressure for those seeking a challenge.

The core gameplay loop is therefore simple and repetitive: select a theme, select an image, solve the puzzle. There is no character progression, no unlockable content hinted at in the available materials, and no scoring system beyond the timer in Chrono mode. The User Interface, from what can be inferred, was likely a simple menu-driven system using mouse input, functional but without any notable flair.

The innovative system, if it can be called that, is the combination of two puzzle genres under one thematic umbrella. Its flaw is its lack of ambition beyond this basic combination. The mechanics are executed competently but without any unique twist or enhancement that would make it stand out from freeware puzzle applications even of its own time.

World-Building, Art & Sound

The “world” of Theme Puzzle is the curated collection of stock photography it presents. The artistic direction is dictated entirely by its four themes. The graphics, handled solely by José Carlos Garcia, would have consisted of selecting and cropping these stock images. We can imagine the visuals: vibrant photos of animals, dynamic sports shots, picturesque travel destinations, and serene landscapes. The goal was not a cohesive artistic vision but variety within familiar genres.

The atmosphere is one of calm focus. It is the antithesis of the high-score arcade frenzy; it is a game designed for a quiet room. The sound design, courtesy of Antonio Arteaga, would have been minimal—likely featuring gentle, looping ambient music and simple sound effects for UI interactions (a click for moving a tile, a soft chime for placement). This audio-visual package serves a single purpose: to create a non-distracting, pleasant environment for puzzle-solving. It is utilitarian, but effectively so for its intended purpose.

Reception & Legacy

The reception for Theme Puzzle is virtually non-existent, which is in itself a powerful statement. MobyGames records no critic reviews and only a single player rating (a 4.0/5, though with no written review). It left no discernible ripple in the critical pond upon its release. Commercially, its multi-region release (2000 in the US, 2001 in France, the Netherlands, and the UK, and even into 2002 according to some sources) suggests a distribution deal was secured, likely through its publishers Crystal Interactive Software, Inc., Cyberium Multi Media B.V., and Musicbank Ltd.—companies that specialized in bundling and distributing such budget software. It was a product meant to be sold, not celebrated.

Its legacy is one of obscurity. It did not influence the puzzle genre; the evolution of puzzle games continued along paths charted by far more influential titles like Lumines, Bejeweled, or Professor Layton. Instead, Theme Puzzle’s historical significance is archeological. It is a perfect specimen of a vanished breed: the commercial, off-the-shelf, budget PC puzzle game. Its legacy is preserved only in digital archives like MyAbandonware and Retrolorean, and in the occasional brand-new, old-stock copy found on eBay, a sealed relic waiting to be discovered by a collector of curious oddities.

Conclusion

Theme Puzzle is not a lost masterpiece. It is not a game that demands reappraisal or a passionate cult following. By any critical measure of ambition, innovation, or artistic achievement, it is a minor, simplistic title. However, to dismiss it entirely would be to ignore its value as a historical document. It exemplifies a complete, functional, and commercially released product built by a tiny team to fulfill a specific, modest market need. It is the video game equivalent of a paperback crossword collection—unpretentious, consumable, and designed for a fleeting moment of engagement.

For the game historian, it represents a fascinating footnote. For the modern player, it offers a stark, minimalist puzzle experience that has been entirely supplanted by more sophisticated and readily available mobile apps. Its place in video game history is firmly in the background, a single thread in the vast and intricate tapestry of the industry, reminding us that for every landmark title that defines a generation, there are hundreds of quiet, humble games like Theme Puzzle that simply were, and then, almost silently, were not.