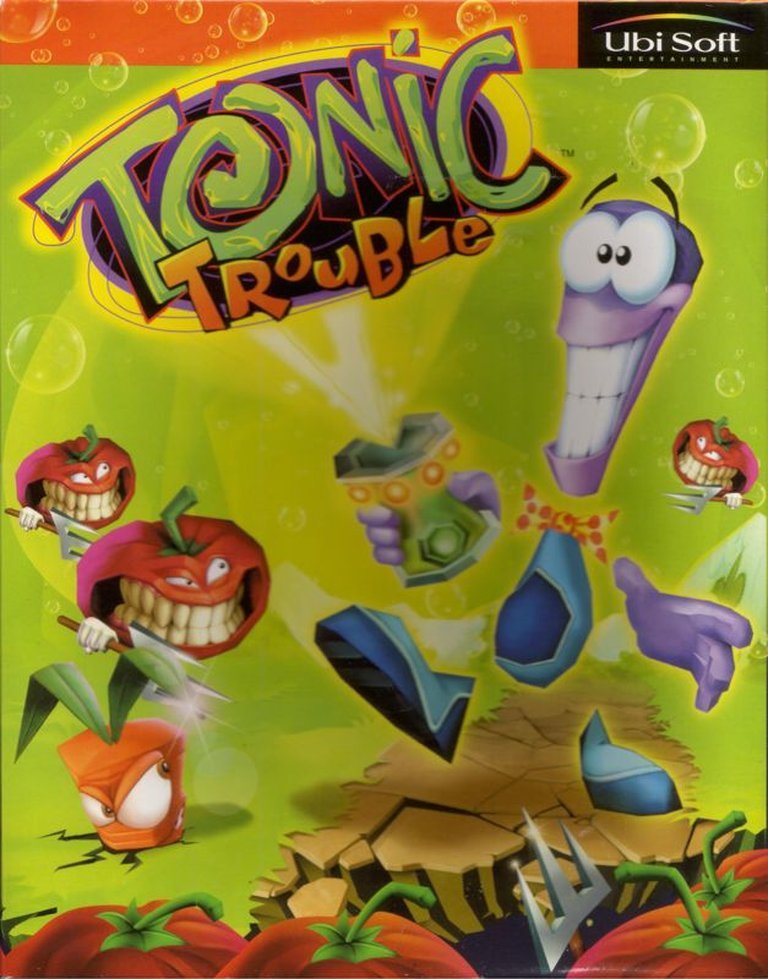

- Release Year: 1999

- Platforms: Nintendo 64, Windows

- Publisher: Acer TWP Corp, Ubi Soft Entertainment Software

- Developer: Ubi Soft Entertainment Software

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Behind view

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Open World, Platform, Puzzle-solving

- Setting: Cartoonish, Earth, Fantasy

- Average Score: 64/100

Description

In ‘Tonic Trouble’, players follow Ed, a well-meaning alien janitor who accidentally spills a can of mutagenic tonic on Earth, triggering a bizarre ecological crisis where rivers flow with sangria and vegetables turn into hostile monsters. Tasked with cleaning up his mess, Ed must journey across a series of surreal, wacky landscapes to recover the scattered tonic can, retrieve six key items, and defeat Grogh the Hellish, a villain who claims dominion over the now-mutated Earth. Inspired by the ‘Rayman’ series and developed by Ubisoft, the game blends 3D platforming with inventive level design, quirky characters, and gradually acquired abilities such as flying with a bow-tie and using a pogo-stick, all wrapped in a humorous, cartoony aesthetic.

Gameplay Videos

Where to Buy Tonic Trouble

PC

Tonic Trouble Free Download

Cracks & Fixes

Patches & Updates

Mods

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

en.wikipedia.org : Tonic Trouble received a mixed response from critics, who approved of the controls, score, level design, and graphics, but criticized the camera system, gameplay, visuals, and its derivative nature.

metacritic.com (68/100): The game that possibly marked the first signs of Ubisoft’s tendency to sometimes release unfinished **** quite rough around the edges products.

mobygames.com (70/100): The game is loony like, and wacky with a Rayman style added. Another fun fact was that the game saves by itself […] resulting with Tonic fun.

gamespot.com (63/100): If this game is remembered at all, it will be as the game that’s not Rayman 2.

gamesreviews2010.com (55/100): Despite its flaws, Tonic Trouble is still a fun and challenging game that’s worth checking out.

Tonic Trouble: A Zany, Flawed Experiment in 3D Platforming

Tonic Trouble, released in 1999 by Ubisoft Montreal, stands as a fascinating, if deeply flawed, artifact of a pivotal moment in 3D platformer history. Developed as a sister project – and, according to some, a technological precursor – to the critically lauded Rayman 2: The Great Escape, the game presents a bold, cartoonish vision of ecological chaos and slapstick alien janitor heroics. Its legacy is complex: a commercial success (selling 1.1 million copies), critically divisive (averaging a 70% Metascore), and ultimately overshadowed by its more polished sibling. My central thesis is this: Tonic Trouble is a valiant, ambitious, and often genuinely fun attempt to translate the essence of 2D, limbless cartoon platforming into 3D, marred by significant technical and design shortcomings that hinder its potential, yet it remains a creatively fertile, contextually vital, and historically revealing entry in the late-90s 3D platformer boom, showcasing both the ambition and the growing pains of Ubisoft Montreal.

1. Introduction: The Janitor with a Can of Chaos

In the twilight of the 5th console generation, as Sony’s PlayStation defined the dominant genre (3D platformers, survival horror, tactical RPGs), Nintendo attempted to leverage its 64-bit hardware via first- and second-party titles like Super Mario 64, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, and Banjo-Kazooie. Meanwhile, third-party developers scrambled to translate their hit 2D franchises into 3D. Ubisoft, fresh off the monstrous success of the flat, limbless Rayman, sought to conquer the 3D space with Tonic Trouble. The hook was irresistible: Ed, a hapless, limbless, lavender-colored janitor, accidentally drops a can of mutagenic ‘Tonic’ during a bug hunt, plummeting to Earth and sparking an ecological disaster. Grogh, a drunken viking, finds the can, drinks it, mutates, and declares himself “Master of Earth.” Ed must clean up his mess, retrieving six parts to fix a catapult and reclaim the can. It’s a premise bursting with absurdist, Saturday-morning-cartoon potential: sentient screws, killer vegetables, rivers of sangria, and a cast of grotesque, limbless misfits. Yet, despite a creative foundation drawn from Day of the Tentacle‘s narrative absurdity and Zelda‘s exploration, the final product embodies the inherent tension between Ubisoft’s lofty ambitions for this “technology demonstrator” and the harsh realities of the N64’s technical limitations and the game’s rushed, troubled development cycle. It’s a game that wants to be a Rayman 2… but exists as its troubled, slightly unhinged cousin.

2. Development History & Context: The Engine That Built a Genre

Tonic Trouble was not just a game; it was a $4 million technological gamble by Ubisoft Montreal, its first major project as a newly established studio. Conceived and initially designed by Michel Ancel, the architect of Rayman, pre-production began in June 1996, placing it in the thick of the N64’s early struggles (pre-Mario 64 release) and the PlayStation’s fast-rising popularity.

- The Ambition: A Tech Foundation: The core project was the development of “Architecture Commune Programmation (ACP)”, a proprietary 3D integration tool and scalable engine built by 50 Ubi Soft developers over 18 months. Its primary function was revolutionary: to put creative control directly into the hands of designers, not programmers. This allowed for complex character rigging, richer environments (moving the needle beyond the blocky worlds of early 3D), and significantly more interactive gameplay. It was designed to leverage the Intel Pentium II for PC, pushing hardware boundaries.

- The Vision: Riley & Company vs. The Real World: Designers like Pierre Olivier Clément explicitly rejected the pure “kill the enemy” loop of contemporaries like Duke Nukem and Quake. Their goal was cerebral: “games like Quake are my favorite games at the moment, but even in these games, the main goal is only to kill the enemy. As a gamer, I want to be able to think, to rationalize my every move… I want to engage in puzzles that require trial and error and deep thought.” They aimed for a stronger emphasis on adventure and puzzle-solving compared to the Rayman 2 team’s focus on action.

- The Platform Horse-Trading: Initially announced at E3 1997 for both Nintendo 64 and Windows, with promises of four-player cooperative multiplayer and a 64DD add-on. The 64DD was quickly abandoned (“puzzle-solving gameplay was incompatible with multiplayer,” per Ubisoft reps), and the PC version became the true beneficiary of the ACP engine. Crucially, Tonic Trouble was designed from the ground up to be the PC title first, ported down to N64.

- The Devastating Delays & The Rayman Shadow: Announced for December 1997, release was delayed six times: Early 1998, April 1998, June 1998, Q4 1998, and finally February 1999. This placed it in direct competition with its own sister project, Rayman 2: The Great Escape, released in October 1999. The E3 1997 version was “in a rough state… lacking animation and suffering heavily from low framerates and stiff controls” (IGN). The final N64 version (August 1999) and PC version (December 1999) resolved these issues, but the narrative was set: Tonic was the belated experiment meant to pave the way for the Rayman 2 masterpiece. The N64 version, constrained by the platform’s texture memory, storage, and processing power, was always destined to be the “weaker” sibling, unlike the PC version, which could utilize the ACP engine and features like Dolby Pro Logic surround sound (licensed in March 1999) and a six-minute animated cinematic (vs. N64’s 2-minute version) enabled by the larger storage of its CD-ROM/DVD-ROM release. The project’s shifting status from precursor to afterthought within the studio must have created immense internal pressure and likely contributed to design compromises and a sense of narrative urgency.

In Context: This was Ubisoft Montreal’s entrance onto the global stage. The studio, composed of 60 programmers, 30 animators, 12 level designers, 12 3D artists, and 4 audio staff (total ~120), was building its identity. The resources poured into ACP weren’t just for Tonic; they were to be the bedrock for Rayman 2, Splinter Cell, Assassin’s Creed, and the entire Ubisoft live-service empire. Tonic Trouble was the proof-of-concept for the engine that would power a generation of mainstream blockbusters. Its mixed reception was, in many ways, a trial run for the studio’s future.

3. Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Absurdity, Ecology, and Incompetence

Tonic Trouble is not deep, but it is densely layered with absurdist themes, presented through two distinct, slightly diverging narratives:

- The N64 (Standard Edition): This version centers on accidental incompetence. Ed’s motivation isn’t heroism but personal responsibility and recovery. The core is a classic “Nice Job Breaking It, Hero!” narrative. His janitorial mundanity (hunting a bug, drinking unknown chemicals) triggers the apocalypse. He’s initially passive, taught by the resistance leader Agent Xyz (a brilliant example of Newspaper-Thin Disguise and faceless, bureaucratic authority), the mad scientist Doc, and his sympathetic daughter Suzy. The goal is mechanical: fix the catapult to reach Grogh’s castle. The theme is earthly decay. The mutated world grotesquely reflects 1990s ecological anxieties: rivers of sangria, jazz-era ocean pianos, psychedelic acid-trip skies, industrial pollution causing anthropomorphic food riots (Attack of the Killer Vegetables!). The mutated Screws, Green Beans, Carrots, Tomatoes (Ketchup), Jalapenos are not just enemies, but symptoms. The land itself is poisoned and in revolt.

- The PC (Special/Enhanced Edition): This version adds crucial character motivation and emotional depth. The opening sees Ed fail an Anguished Declaration of Love to an unseen girl, a Goofy Print Underwear-wearing boyfriend chasing him. This personal failure directly leads to the Tonic spill (from a garbage chute, not a Janitor’s mistake). His quest becomes redemption: for relationship failure, for career failure (literally just a janitor), for cosmic failure. It frames the entire disaster not as a random accident, but as a result of his own insecurity and ineptitude. It also establishes Grogh’s tragic arc: a drunkard kicked out of a bar, finding transformation not as a choice, but a means of From Nobody to Nightmare (“This time drinks are on ME!”). He resents the Pharmacist’s control over the empire, making him a Sympathetic Villain (TV Tropes). The quest for the catapult parts becomes a road trip of personal growth for Ed.

- Thematic Resonance: While the surface is cartoonish, the game engages with several potent themes:

- Ecological Horror (Green Aesop): The game is arguably one of the first major titles to depict an ecological disaster caused by careless individual action directly affecting the environment, years before Avatar or climate-focused games. The mutation is not magical; it’s technological (a can of “tonic”), and the consequences are immediate, grotesque, and deeply physical. The world isn’t just dangerous; it’s angry (Gaia’s Vengeance per TV Tropes). Suzy’s ending speech (“Due to contamination…”) is a clumsy, abrupt forces-of-nature moral, but the preceding 12 levels show the horror, making it conceptually ahead of its time.

- Incompetence as a Power: Ed is an Almighty Janitor (TV Tropes). His lack of innate power (no limbs!) is his defining characteristic. He needs gadgets (bowtie, pogo-stick, diving helmet) to compensate for his inherent physical limitations. His Super Ed transformation (via popcorn, a product placement parody) is grotesque, Top-Heavy Guy (TV Tropes), a temporary, clumsy power overwhelming his wiry frame. He’s the anti-hero who actively likes being a janitor.

- Absurdism & Anti-Structure: The world is illogical. Noodle Implements: Doc’s catapult is built from springs, propellers, jumping stones, dominoes, and piggy banks. The Faceless: Agent Xyz, never seen. The Logic of Dreams: Lava is traversed on a pogo-stick; rivers are poison. The narrative beats are paper-thin, but the settings and event sequences embrace surreal nonsense.

- Subversion of Heroism: The ending is an A Winner Is You (TV Tropes) failure. Ed defeats Grogh, retrieves the can, but the world’s restoration is Take Our Word for It (TV Tropes). No cutscene shows the reset. We only see Ed and Suzy’s reactions, followed by a static screenshot. It’s a bleak, anti-climactic note for a game about cleaning up mess.

Character & Dialogue: Characters are limbless for stylistic unity with Rayman, but the design philosophy differed. Ed is Vocal Dissonance (TV Tropes) (beta voice sounds juvenile vs. the final mature voice). Grogh, in the final version, has a booming, imposing voice, contrasting the drunken, unnecessary viking helmet he gains post-transformation. Suzy is the Mad Scientist’s Beautiful Daughter (TV Tropes), a white-maned, hourglass-figured limbless himbo. Doc is an Eyes Do Not Belong There anomaly (one eye on top of his head in some versions, symmetry in N64). The dialogue is functional, functional humor (“Mööp!”), and the save system (“Ed, Tonic, Hands, Feet, Body, Head.”) feels like a meta-joke on the game’s own character model limitations.

4. Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Slippery, Sometimes Broken Toy

The gameplay is a wonderfully frustrating cocktail of innovative ideas and deeply flawed execution.

- Core Movement & Identity: Ed is distinct. His limbless body moves with a unique, heavy, slightly sluggish inertia. He exists in a 3rd-Person Behind View, but suffers severe, inconsistent camera issues (noted by Banjo-Kazooie, Mario 64 contemporaries). The camera (“mööp!”) often obstructs critical jump targets, fails to follow through complex geometry (especially in Glacier Cocktail), or obscures enemies (GamePro, GameSpot, AVault). This is the game’s most persistent, game-breaking flaw – a “Craptacular Disaster” (GameRevolution) and a “shining example of how not to do a platform game” (VideoGames.com). Movement itself is impacted by the “air has the consistency of butter” (PC Player critic) complaint. Jumps feel imprecise, landings soft, and momentum hard to track, especially on N64’s analog stick.

- Core Combat: Ed unlocks combat via Super Ed (consuming Newman’s Own branded Popcorn via vending machines). This temporary, grotesque Top-Heavy Guy state gives him kicks and slaps. Standard combat relies initially on a plunger gun (projectile), then a stick for melee, and the Super Ed state. This locked progression (no combat until Super Ed) is brilliantly subversive and frustrating. Enemies like Killer Vegetables require specific tactics (e.g., carrots only die to vertical stick jumps). The peashooter is earned late, offering first-person aiming, a unique twist for a 3D platformer.

- Gadgets & Progression: This is where Tonic shines. Gadgets are built by Doc and are narratively integrated. The bow tie (jetpack), diving helmet, Chamaleon Powder (Revolorizer) for Dressing as the Enemy (TV Tropes), and pogo-stick are not just tools; they’re story beats. Gaining the bow tie represents mastering flight; the pogo-stick is Escherian lunacy (“Convection, Schmonvection” TV Tropes). The gadgets introduce non-linear progression: once acquired, Ed can re-explore previous worlds, finding new puzzles, secrets (via Bonus Spheres), and routes. This is collect-a-thon design (TV Tropes), 12 distinct, medium-length levels (ranging from South Plain, The Canyon, Grögh’s Castle, Doc’s Lab, Ski Slope, Vegetables HQ) filled with red orbs, switches, and paths.

- Puzzle Design & Challenge: The game’s identity. Building the catapult requires fetch quests (6 items) and puzzles. A standout is passing as Grögh to trick a guard (Villain Shoes, TV Tropes). Puzzles often require trial and error (as Clement intended), like timing sequences, environmental logic (ice pillars melting over time), or impossible hourlyglass figures (shaping platforms). However, difficulty is mal dosée (poorly tuned). Glacier Cocktail is notorious for its punishing maze-like structure, requiring pixel-perfect timing, often described as taking “hours to get out” (Moby user Chase Bowen). A literal Puzzle level (TV Tropes) exists. Fail states are frequent, save points are only at portals/level ends (beneficial for N64 controller pack, frustrating otherwise).

- The N64 vs. PC Divergence: The controller differences are stark. The N64 used the 64-Drive for storage, enabling the portal save system. The PC, with CD-ROM, utilized drives/programs in the game world for saves, blending interface and narrative. The PC also had Dolby Surround 10-track system music, dynamic audio (intense combat vs. melancholy solitude, as stated), and vastly superior visuals (texture details, lighting, animation fidelity). The N64 version suffered from “sparse textures,” “low-res and fuzzy characters” (GamePro), “jumbled visuals” (GameRevolution), and “blurry, soft, indistinct” graphics (IGN).

5. World-Building, Art & Sound: Drawn from the Cartoons of the 60s

- Visual Design: “Our inspiration came essentially from the cartoons of the 60s” (Geoffroy DeCrecy, rendering lead, per IGN Q&A). This is evident everywhere: the bold, flat colors, the thick black outlines, the exaggerated proportions, the absurd proportions, the limbless bodies, the grotesque caricatures (the Huge Barman, Blue Dog, cyborg duck, giant snail). Worlds are texture-mapped, built with 3D Studio Max from hand-sketched concepts, colored in Photoshop/Painter. The result is immediate, iconic, and wildly inconsistent. The PC/N64 discrepancy is massive. The PC’s “stunning 3D graphics,” “great” sound effects, and music (GameZone) created a “cute and fun” (GameZone) vibe. The “distracting, eyesore” colors, “simply horrible” graphics, and “bland and unoriginal” level design (VideoGames.com) on N64 are a direct result of downscaling from the PC’s high-poly models and textures to N64’s limited 4MB texture RAM. Worlds like Ski Slope (Fruit Punch), South Plain (Sangria), Vegetables HQ (Lava), and Reversed Pyramid (Sand) are conceptually strong but visually muddy on N64.

- Sound Design & Music: A critical strength. The score by Eric Chevalier (6 months, 1 music lead, 5 sound editors) is a standout example of early dynamic music. Moving from exploration to combat triggers a shift from ambient tones to intense, nerve-wracking (per IGN) cues. It’s not just thematic; it’s **contextual. Tracks are long (10 tracks), avoiding the repetition of contemporaries. The sound effects are cartoony (user Chase Bowen), zany with a Rayman style (Qlberts). They enhance the immersion in a goofed-up world. Sound is the game’s most consistently enjoyable technical aspect. However, the “very few sound effects” (ben Stahls, Casamassina) and the “forced” voices (GamePro) are noted. The Kiss of Life from Suzy (Game Over screen) stays as absurd a moment as any in gaming.

6. Reception & Legacy: The Footnote That Was a Foundation

Tonic Trouble was born into a bloodbath of 3D platformers. It faced direct competition from Banjo-Kazooie (N64), Gex: Enter the Gecko (PS1), SpongeBob SquarePants: Legend of the Lost Spatula (PS1), Tork: Prehistoric Punk (PS1), and, most devastatingly, Rayman 2: The Great Escape (PS1, N64).

- Critical Reception (70% Metascore): Reception was polarized by platform and expectation.

- PC: “Well over average” (Moby average 3.4/5, GameZone 8.5/10). Praised for diverse challenging puzzles (GamePro), stunning graphics, great music, fun story (GameZone), responsiveness, exploration, humor (Next Gen), “solid controls” (Game Informer). Criticized for automatic saves, camera (Informer, Power Play, GameSpot), and derivative nature (Jones).

- N64: “Knappes Gut” (Total!, 78%) to “Craptacular Disaster” (GameRevolution, 0%). Praised for level design, control scheme, wide variety, solid controls (EGM, Informer, Pro), fun gadgets, replay value, music (Next Gen, Power Play), quirky humor, exploration (Nintendo Power, Game Play 64). Criticized for “the camera”, “unrefined controls”, “stiff movement”, “annoying character“, “boss fights“, boring narrative (EGM, Classic-games.net, GameSpot, GameRevolution, AVault), and “ripping off” Rayman (Qlberts, GameStar).

- Commercial Success (1.1M): Despite the critical divide, it sold well, benefiting from Ubisoft’s marketing (the Newman’s Own partnership with $10 rebate coupons helping retail) and its culturally appropriate “kiddie” ESRB ‘E’ rating.

- Legacy: The Unborn Franchise: Its legacy is dual-faceted.

- The Cult Classic: To players who did experience it, it’s a unique, quirky, genuinely fun, and challenging platformer. Its catchy music, surreal humor, innovative gadget progression, and environmental themes create a memorable, offbeat experience.

- The Litmus Test for Ubisoft Montreal: Its **true