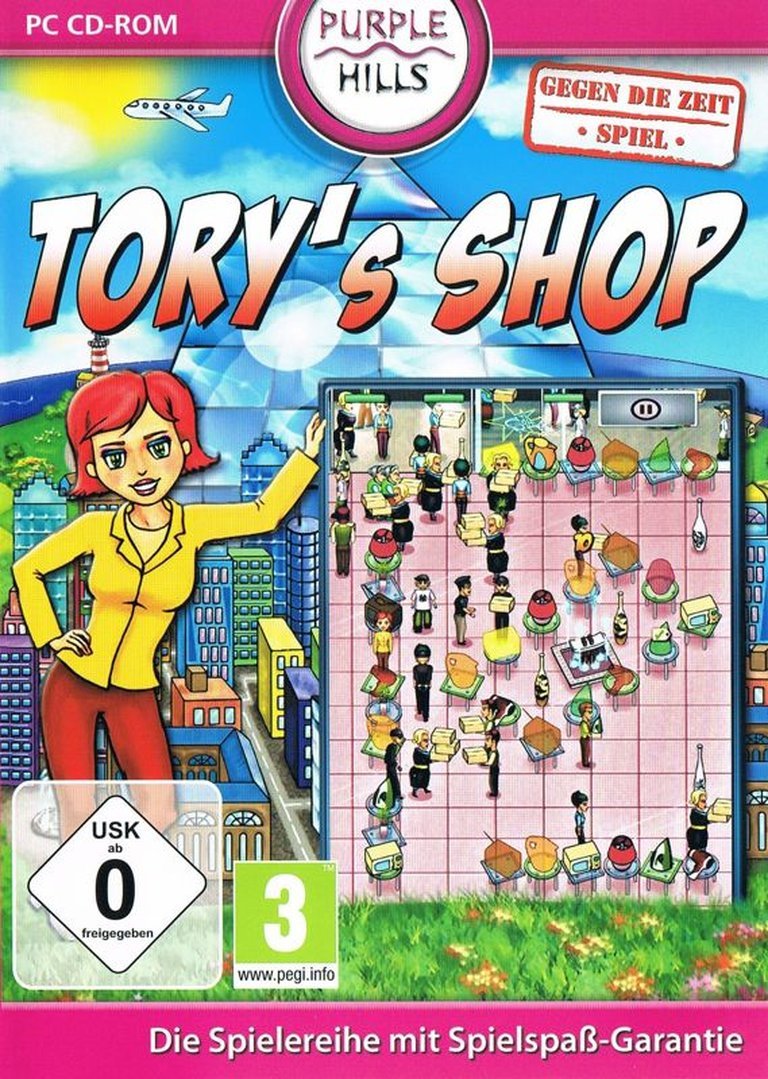

- Release Year: 2010

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: S.A.D. Software Vertriebs- und Produktions GmbH

- Developer: Rooster Games

- Genre: Action

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Time management

- Setting: Shop

Description

Tory’s Shop is a time management action game where players step into the shoes of Tory, who inherits and runs a small shop from her uncle. Across 60 levels, the core gameplay involves filling shelves, collecting money from customers, hiring additional staff with earned profits, and strategically expanding the shop. Success hinges on speed and efficiency, as faster service leads to greater earnings, enabling continuous growth and overcoming increasingly demanding challenges in a fixed, diagonal-down perspective setting.

Gameplay Videos

Tory’s Shop: A Forensic Review of an Obscure Artifact from the Casual Gaming Boom

Introduction: A Ghost in the Archive

To speak of Tory’s Shop is to speak of a silent echo. Released in May 2010 for Windows by the German publisher S.A.D. Software Vertriebs- und Produktions GmbH and developed by the enigmatic Rooster Games, this title exists not as a remembered experience but as a sparse data point in the vast museum of video games. Its MobyGames entry, contributed in 2017, is a skeleton: a genre label (“Action,” though clearly misapplied), a PEGI 3 rating, a description of a time-management shop sim, and a credits list for five individuals. There are no critic reviews, no player reviews, no screenshots beyond placeholder thumbnails, no documented sales figures. It is, in the parlance of archival science, an “absent presence.” This review, therefore, is an act of reconstruction—an attempt to place this faint signal within the broader频谱 of its time, to understand what Tory’s Shop represents as a cultural and design artifact, and to confront the profound gaps in our collective gaming memory. My thesis is that Tory’s Shop is not merely a forgotten game but a perfect specimen of a specific, now-faded stratum of the early 2010s casual game market: the downloadable, modest-budget, service-oriented time-management title, whose legacy is one of quiet proliferation rather than critical acclaim.

Development History & Context: The Rooster in the Eastern European Coop

The development history of Tory’s Shop is as obscure as the game itself. The studio, “Rooster Games,” leaves no other trace on MobyGames or in mainstream databases. The credits, however, tell a story of micro-team development common in the Eastern European casual and budget game scene of the late 2000s. The core creative force appears to be Alexander Petukhov, who serves as Programmer, Level Designer, Interface Designer, and Story writer. This is the hallmark of a developer wearing every hat, a necessity in small-scale projects. His brother, Dmitry Petukhov, is the 3D-Designer, while Helen Bulgakova handles 2D-Design. The producers, Artem Yershov and Anastasia Yurkina, are credited on 19 and an unspecified number of other games respectively, suggesting they were part of a small, prolific network or studio churning out titles for the burgeoning digital distribution and budget CD-ROM markets.

The technological constraints were those of mid-range PC gaming circa 2010: DirectX 9.0 compatibility, a requirement for 16MB of 3D video memory (a modest even then), and a CPU benchmark of a Pentium III 600MHz. This points to a game built for accessibility, targeting low-spec machines and aiming for the widest possible install base. The “Fixed / flip-screen” perspective and “Diagonal-down” view were standard for 2D and isometric casual titles, minimizing art asset demands and simplifying UI design. The business model was “Commercial” on “CD-ROM,” placing it squarely in the transition period where physical retail still mattered for casual gamers, but the rise of digital storefronts like Big Fish Games, Yahoo! Games, and Alawar’s own portal (as seen in the blog source) was creating a new distribution ecosystem. The release date, May 2010, is fascinatingly sandwiched between the massive blockbuster launches of Red Dead Redemption (May) and Toy Story 3: The Video Game (June). While AAA titles fought for headlines, dozens of titles like Tory’s Shop flooded the “arcade & action” and “time management” categories of digital retailers, serving a vast, under-discussed audience.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Banality of Capital

If Toy Story 3: The Video Game (included in the sources as a bizarre comparative artifact) represents the zenith of licensed, narrative-driven family gaming, Tory’s Shop represents its antithesis: the pure, unadorned mechanics of labor. The narrative is conveyed through the game’s title and Moby description: “Tory inhabits a small shop from her uncle and runs it now.” This is not a story of emotional journeys or character arcs; it is a premise of economic succession. The “plot,” such as it is, is the player’s own progression from shop novice to retail mogul.

Thematically, the game is a distillation of capitalist productivity. The core verbs are “fill the shelves,” “get money from customers,” “hire additional staff,” and “expand your shop.” There is no mention of a villain, save perhaps the abstract concept of “thief” mentioned in the Alawar blog (“keep an eye on the thief”). The conflict is systemic: the pressure of time (“The faster you are, the more money you make”) against the escalating complexity of customer demands (“helping old ladies remember what they want to buy,” “cleaning up after messy teenagers”). It simulates the service economy’s relentless pace and the managerial calculus of investment versus reward. Unlike the Toy Story game’s themes of loyalty, growing up, and found family, Tory’s Shop is about efficiency, growth, and financial hygiene. Its world is not one of anthropomorphic toys but of shelves, cash registers, and customer satisfaction meters. It is, in its own crude way, a more honest simulation of a real-world job than most “serious” business sims.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: The Loop of Retail肉体

The gameplay loop, as described, is the classic “Diner Dash” or “Restaurant Empire” formula applied to a generic shop. The player must manage a real-time flow of customers who enter, request items from specific shelves, purchase them, and leave. The core skill is spatial and temporal triage: memorizing shelf locations, prioritizing customers (presumably based on patience meters), and physically moving Tory (or her hired staff) to complete actions. The “60 levels” progression likely introduces new variables: more customer types with complex orders, thieves that require interception, messes that require cleaning, and the need to strategically reinvest profits into staff (to parallelize tasks) and shop expansions (to increase capacity and revenue).

The innovation, if any, is likely in its simplicity and pace. For its target audience—likely casual PC gamers, possibly older demographics—the rules are immediately legible. The “flip-screen” visual style suggests discrete, screen-sized areas of the shop, a design that focuses attention and simplifies pathfinding. The lack of a complex critique in the provided sources implies a functionally adequate but unremarkable implementation of a well-established genre template. There is no indication of deeper systems like supply chain management, dynamic pricing, or intricate customer relationship mechanics. It is a game about execution, not strategy; a test of reflexes and memory under pressure, not long-term planning. The absence of reviews means we cannot analyze its UI clarity, control responsiveness, or difficulty curve, but its continued listing on sites like Alawar and its inclusion in “Time Management” collections suggests it fulfilled its core function competently enough to remain available.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Aesthetic of the Generic

Tory’s Shop’s world is the universal, placeless “small shop.” There are no specific cultural markers, no distinct architectural style. This is a deliberate design choice for a casual game aiming for global appeal—a Scandinavian player, a Brazilian player, a Midwestern American player can all see “their” shop. The 3D-Designer (Dmitry Petukhov) and 2D-Designer (Helen Bulgakova) would have worked within a tight, stylized low-poly or 2D sprite aesthetic, common for budget titles of the era. The perspective is “Diagonal-down,” offering a clear, isometric-like view of the play space, maximizing visibility for management tasks. The “Fixed / flip-screen” nature means the art team could create a handful of detailed, reusable room layouts rather than one vast, seamless world, a significant resource saver.

Sound design, unmentioned in the credits, would almost certainly follow the casual game convention: a cheerful, repetitive loop of light jazz or synth-pop music and a handful of intuitive sound effects for cash registers, customer exclamations, and item pickups. The goal is pleasant background noise, not an immersive soundscape. The atmosphere is one of busyness, not exploration. This aesthetic serves the gameplay perfectly: it is functional, clear, and non-distracting, prioritizing the player’s ability to parse the spatial puzzle of the shop floor at a glance. It is the visual equivalent of a well-organized stockroom.

Reception & Legacy: The Unreviewed Millions

Here, the historical record vanishes. Metacritic has no critic reviews for Tory’s Shop N’ Rush. MobyGames has none. No major publication from 2010 appears to have covered it. This is not an anomaly for its genre and market segment. These titles existed in a parallel press universe covered by casual gaming portals (like GameHouse, Big Fish Games’ blogs, or Alawar’s own channels) and aggregated on “top casual games” lists, not in Edge, IGN, or Game Informer. Its legacy is not one of critical discussion but of quantitative presence.

Its influence is indirect but significant. Tory’s Shop is a drop in the ocean of the “time management” boom that crested in the 2000s and early 2010s, pioneered by Diner Dash (2004) and spawning countless imitators like Cake Shop, Cook Serve Delicious, and Shop Titans. It represents the formula’s global dispersion and localization. The fact that it was published by a German company (S.A.D.) for the European/Western Windows market, developed by a likely Eastern European team, exemplifies the transcontinental pipeline of casual game development. Its “success” is measured not in Metascores but in its continued availability on platforms like Alawar and its inclusion in “50 Time Management Games” listicles years later. It is a durable, if uncelebrated, component of a genre that provided a low-stress, accessible gaming experience for millions who never touched a console controller. Its primary historical value is as a data point showing the sheer volume and geographic diversity of game production outside the AAA spotlight.

Conclusion: The Case for the Unremarkable

Tory’s Shop is not a lost masterpiece. It is not a cult classic waiting for rediscovery. It is, by all available evidence, a proficient, anonymous, and utterly forgettable entry in a genre defined by its comforting predictability. Its value lies not in its artistry or innovation but in its typicality. It is a Rosetta Stone for understanding a specific economic model of game development: small teams, modest budgets, clear genre templates, and distribution through niche channels targeting a non-traditional gaming audience.

To review it with the same criteria as Toy Story 3—with its cinematic ambitions, cross-platform consistency, and Pixar oversight—is a category error. Tory’s Shop had no such ambitions. Its goal was to occupy 60 minutes of a player’s afternoon with a satisfying, escalating series of tasks, and then to be forgotten until the next installment or a similar game. In that, it likely succeeded for its intended audience. Its true verdict is written not in reviews but in its obscurity. It is a perfect example of the vast, submerged continent of video game history—titles that sold decently, bored no one, innovated nothing, and left no trace beyond a digital footprint and a credit line for Alexander Petukhov. In the canon of gaming, Tory’s Shop is a blank page. Its significance is that it was ever there at all.