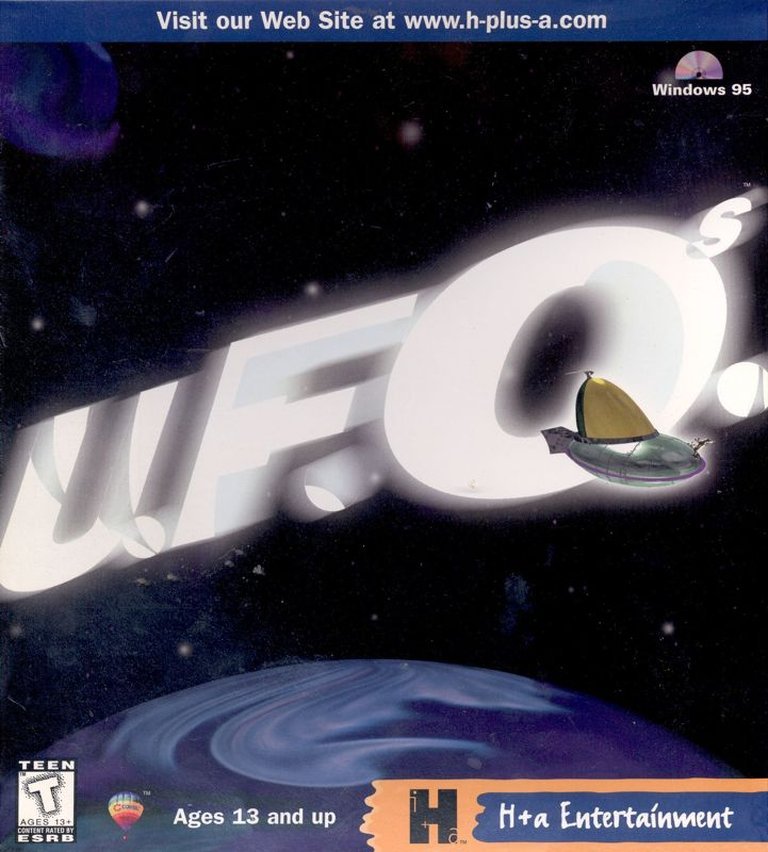

- Release Year: 1997

- Platforms: Macintosh, Windows

- Publisher: AIM Productions NV, Akella, ARI Data CD GmbH, Corel Corporation, Hoffmann + Associates Inc.

- Developer: Artech Digital Entertainment, Ltd.

- Genre: Adventure

- Perspective: 3rd-person (Other)

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: Arcade, Graphic adventure, Puzzle elements

- Setting: Futuristic, Sci-fi

Description

U.F.O.s is a comedic sci-fi graphic adventure where players assume the role of Gnap, an alien stranded on Earth after his spaceship crashes. Set in a wacky, hillbilly-inspired environment, the game revolves around puzzle-solving—often involving physically coercing non-player characters with a remote control—to gather parts and repair the ship, all while enjoying mature humor and embedded arcade mini-games.

U.F.O.s Guides & Walkthroughs

U.F.O.s Reviews & Reception

myabandonware.com : Not as vibrant as Stupid Invaders, but good to look at nonetheless.

U.F.O.s: A Cult Classic of Anarchic Absurdity

Introduction: A Purple Sausage from the Stars

In the grand annals of point-and-click adventure games, few titles are as simultaneously celebrated and obscure, as divisively loved and dismissed, as Artech Digital Entertainment’s 1997 oddity, U.F.O.s (released in Europe as Gnap: Der Schurke aus dem All). Upon its release, it was a splash of garish, irreverent color in a genre increasingly dominated by cinematic noir and epic fantasy. Here was a game about a one-eyed, purple, sausage-like alien crash-landing in the Ozarks, accompanied by a dimwitted platypus, tasked with repairing his ship by bludgeoning hillbillies and solving puzzles through cartoonish violence. The critical reception was a perfect bell curve of contempt and adoration, with scores ranging from a derisory 21% to a perfect 100%. This review posits that U.F.O.s is not merely a forgotten curio but a deliberate, if flawed, masterpiece of anti-design—a game that weaponizes absurdity, rejects narrative pretension, and embodies the anarchic spirit of mid-90s cable animation like Ren & Stimpy and Duckman. Its legacy is that of a cult classic ahead of its time, a game so unapologetically niche in its humor and structure that it burned brightly for a select few before fading into the preservationist’s domain, where it has found a second life via ScummVM and passionate abandonware communities.

Development History & Context: The “Wacky Hillbilly Space Adventure”

Studio & Vision: U.F.O.s was developed by Artech Digital Entertainment, a Canadian studio with a robust portfolio of licensed titles—Monopoly: Star Wars, Jeopardy!, Qbert—indicating a team adept at working within established properties. With *U.F.O.s, they created an original IP, and the design ethos is explicitly stated in their own description: a “Wacky Hillbilly Space Adventure Game.” This was not an attempt to reinvent the adventure genre’s narrative capabilities but to distill its gameplay to a absurdist, gag-driven core. The creative leads—producers Rick Banks and Paul Butler, game designers Josh Bridge, Phil LaFrance, and Cory Humes—envisioned a world where every interaction could trigger a unique, often violent, cartoon skit.

Technological Constraints & Landscape: Released in 1997, the adventure genre was at a crossroads. LucasArts was winding down its classic output, and Sierra’s realistic SCI1.1 engine was being phased out. 3D acceleration was becoming standard, but pre-rendered 2.5D backgrounds with hand-drawn sprites (a technique used in Final Fantasy VII and Grim Fandango) were still viable for a mid-budget title. U.F.O.s employed this hybrid approach: “800×600 24-bit graphics” (per the box) with “screens jam-packed with animations.” The technical specs from MobyGames—requiring a Pentium, 16MB RAM, SoundBlaster, and a 2x CD-ROM—place it firmly in the late-CD-ROM era, where full-motion video and high-fidelity audio were selling points, but Artech invested in animation density over cinematic length.

Publishing & Localization: The game’s publication history reflects the fragmented European market. Corel Corporation and Hoffmann + Associates handled North America. In Germany, it was localized by ARI Data CD as GNAP: Der Schurke aus dem All (literally “GNAP: The Villain from Outer Space”), a title change that puzzled reviewers. AIM Productions brought it to Belgium (1998), and Akella to Russia (Приключения Инопланетянина / “Adventures of an Alien”). This scattered release strategy, common for smaller publishers, likely contributed to its low commercial profile outside dedicated adventure circles.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Logic of the Lunatic

Plot as Minimalist Framework: The plot is a bare-bones McGuffin quest. Gnap, an alien whose ship runs on “alien gas,” crash-lands in a farmer’s pigpen. His ship is wrecked. He must find parts to repair it. That is the entire narrative engine. There is no sprawling conspiracy, no moral dilemma, no philosophical quest. The story exists solely to string together a series of encounters with the bizarre residents of rural Earth.

Characters as Vessels of Absurdity: The cast is a rogues’ gallery of hillbilly and small-town grotesques, designed to be mocked, outwitted, or physically assaulted.

* Gnap: The silent protagonist. He speaks in “strangled breathy noises” and “telepathic electronica” gibberish (as per My Abandonware‘s description), his emotions conveyed entirely through squash-and-stretch animations. This aligns him with silent comedy icons like Buster Keaton, though with a distinctly Tom & Jerry-esque capacity for pain and brutality.

* The Platypus: The dimwitted sidekick, acquired early by freeing him from a bear trap. His role is functionally identical to Max in Sam & Max, serving as a tool for remote puzzles. However, U.F.O.s leans into the cruelty: the platypus is seemingly invincible, allowing forsequences like luring him into a dog’s jaws or onto a chopping block. He is a willing victim of the game’s slapstick violence.

* The Humans: They are not characters but archetypes of “psychotic wackos”—two-headed hillbillies, aggressive bikers, eccentric townsfolk. Their behavior is non-sequitur and hostile, justifying Gnap’s violent solutions. As Adventurearchiv noted, the comic violence is “sometimes quite brutal with dripping comic blood,” pushing its “Teen” ESRB rating.

Themes: Anarchic Anti-Culture: The game’s themes are not explored but embodied. It is a satire of American hillbilly and small-town tropes, filtered through a lens of complete nonsense. The underlying message, if one exists, is that the world is irrational, and the only logical response is to match it with equal, over-the-top absurdity. The humor is “black” (Adrenaline Vault), “tasteless and even offensive” (Quandary, Metzomagic), and explicitly compared to the shock-value cartoons of the era. It rejects “cultural significance” (as the box proudly states) in favor of pure, consequence-free comedic cruelty. The final “freak show/dance party” in Cityville represents the apotheosis of this—a celebration of the bizarre as the norm.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Inventory, Violence, and Intermission

Core Loop & Interface: U.F.O.s is a classic point-and-click adventure. The interface is minimalist: right-click cycles through cursors (Walk, Look, Use, Platypus), left-click executes. Inventory is accessed via a “zappy remote control” icon in the top-right corner, a clever diegetic UI that fits the alien theme. Puzzles are almost entirely inventory-based or involve directing the platypus. The design philosophy is “use every item on everything” (My Abandonware), with a small, logical environment (roughly 5 locations, ~25 items) encouraging experimentation.

Innovative/Flawed Systems:

1. The Remote Control Mechanic: The ability to “tell some NPCs how to help” via a remote control is the game’s signature twist. It formalizes the common adventure trope of using a companion, making it a core systemic mechanic. However, it is limited to specific, scripted NPCs and interactions, not a full party system.

2. Nonsequiturs as Feedback: The designers paid obsessive attention to “every little detail” (Just Adventure). Attempting almost any action—logical or illogical—triggers a unique, often violent, short animation. This turns trial-and-error from a frustration into a source of comedy. As Adrenaline Vault noted, “the humor… makes it a game no cartoon fan wouldn’t enjoy.”

3. Arcade Sequences: Three mandatory arcade sequences and a Space Invaders mini-game break the point-and-click pace. They are:

* A truck-driving roadkill collection.

* A Mortal Kombat-esque tongue-wrestling match for gum.

* A final, more complex arcade challenge.

These are widely cited as the game’s weakest elements. The tongue fight, in particular, is “frustrating” and “more frustrating than complicated” (My Abandonware), a jarring difficulty spike in an otherwise accessible game.

4. Puzzle Logic & Length: The puzzle logic is generally logical within the game’s insane world (My Abandonware: “you will be able to work out most things logically by paying attention to small details”). However, some are “pretty illogical” (GameStar). The greatest criticism is the game’s extreme brevity. At “two or three short gaming evenings” (Adventurearchiv) or “a couple of hours” (Quandary, My Abandonware), it feels more like a proof-of-concept than a full product. As PC Joker quipped, the only “schurkische” (villainous) thing is that it doesn’t last long.

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Masterclass in Cartoon Grit

Visual Direction & Animation: This is the game’s undisputed triumph. The aesthetic is pure 1990s prime-time animation—Ren & Stimpy meets Duckman. The 2D sprites, drawn by a large team including Josh Bridge and Phil LaFrance (“SILLY LOOKING DRAWINGS BY”), are exaggerated, rubbery, and packed with personality. Animations are fluid and context-sensitive. Gnap’s silent reactions—scratching his head, swelling his cranium in thought—are a masterclass in visual storytelling. The pre-rendered 3D backgrounds (“THREE DIMENSION SCENICS” by Stephen and Jay Young) are rendered in a stylized, toy-like fashion that perfectly complements the sprites, creating a cohesive, playable cartoon world. Adventurearchiv specifically praised the “cartoon-style graphics,” which have aged remarkably well due to their stylization.

Sound Design & Voice Acting: The audio is a delightfully unpolished gem. The soundtrack is a collection of “zeichentricktypischen Soundeffekten” (cartoon-typical sound effects) and music pieces (PC Joker). Voice acting is provided by the development team themselves, yet it brims with “character and an over-the-top passion” (Collection Chamber). Because Gnap is silent, the human characters’ lines are few but memorable, delivered with a manic, amateur energy that enhances the off-kilter vibe. The sound effects—boings, crunches, zaps—are perfectly timed and contribute massively to the physical comedy.

Atmosphere: The atmosphere is one of relentless, nerve-jangling whimsy. The Ozark setting is rendered as a place of perpetual, friendly menace. The color palette is bright but grimy, the environments (pigpens, bars, supermarkets, circuses) feel lived-in and hostile. The game never takes a breath; background animations (a cow mooing, a sign spinning) constantly reinforce the feeling of a living, agitated cartoon.

Reception & Legacy: The Great Divide

Critical Schism: The 68% MobyScore masks a catastrophic split. The top reviews (100%, 91%, 90%, 90%) are ecstatic.

* Tap-Repeatedly: “A great straight adventure game… design is really clever.”

* Just Adventure: “So many little features abound the game… never did I once think they had rushed.”

* Adventure Gamers: Ranks it “right up there with Grim Fandango and the Pandora Directive… incredibly polished.”

* Adrenamine Vault: “The funniest game I’ve seen all year.”

The bottom reviews (29%, 21%) are scathing.

* PC Action: “Humor so simple-minded it almost hurts… cannot call it the ‘ultimate comic game’.”

* PC Games: “Humor frequently more than embarrassing… hardly measurable complexity… can be finished by trying things out within a few hours.”

* PC Joker: Critiqued “stubborn” mouse control and short length, calling it a “preiswerten Spaß” (cheap fun).

The central debate is whether its humor is brilliant or brainless, its brevity a strength or a fatal flaw. German reviewers were particularly harsh on length and puzzle simplicity.

Commercial Performance & Obscurity: The game was a commercial afterthought. Published by Corel (better known for WordPerfect) and small European distributors, it had minimal marketing. As the GOG Dreamlist votes and abandonment status show, it slipped through the cracks. Its obscurity is a tragedy of timing and niche appeal. As Collection Chamber notes, it was “an unfortunate casualty of a small-time publisher” during the adventure genre’s decline.

Preservation & Cult Status: Here, U.F.O.s has seen a resurrection. Its inclusion in ScummVM (as noted on the wiki page and by Collection Chamber) is a massive testament to its engineering and the dedication of fans. This allows it to run on modern systems with minimal fuss. The GOG Dreamlist memories are poignant:

* “@Guybrush88”: “Unique strangeness… absurd situations and surreal logic.”

* “@Nhor”: “Replayed it like hundreds of times in my childhood… this game clicked with me so much.”

* “@DoNotFeedMe”: “Remembered liking the overall vibe and humor.”

These testimonials reveal a game that, for a certain audience, created a powerful, nostalgic bond precisely because of its unapologetic weirdness and short, replayable burst of comedy.

Influence: Direct influence is minimal. It stands as a singular artifact. However, its DNA can be felt in later absurdist adventures like Stupid Invaders (which Quandary and My Abandonware explicitly compare it to) and the modern wave of “anything goes” indie adventures that prioritize joke density over narrative cohesion. It is a precursor to the “streamer bait” genre—games played for the spectacle of reaction.

Conclusion: The Beautiful Failure

U.F.O.s is a magnificent, deeply flawed, and profoundly important game. It is a beautiful failure—a game that succeeds so completely at its stated goal of being a “Wacky Hillbilly Space Adventure” that it alienates anyone expecting a conventional adventure. Its polish in animation and comedic timing is undeniable. Its commitment to gag-per-minute pacing is relentless. Its systemic use of the platypus as a tool is clever.

But it is also frustratingly short, with arcade sequences that feel like concessions to a publisher nervous about pure adventure gameplay, and a humor so black it turns off as many as it delights. Its MobyScore of 6.9 is a perfect numerical summary: above average, but with glaring, acknowledged weaknesses.

Its place in history is not as a genre-defining milestone, but as a * defiant outlier. It proves that the adventure game format could house something as purposefully nonsensical as a *Looney Tunes short. In an era where adventure games were straining for cinematic gravitas, U.F.O.s remembered they could be cartoons. It is the game equivalent of a bizarre, forgotten cartoon you might have caught on late-night TV as a kid—confusing, hilarious, slightly disturbing, and utterly unforgettable. For those who clicked with its紫色香肠外星人和他的鸭嘴兽伙伴, it remains a cherished, repeatable piece ofInteractive absurdism. For everyone else, it remains a perplexing, 6.9/10 curio—a testament to the fact that in the 1990s, you could, for a brief moment, buy a CD-ROM game about an alien bludgeoning hillbillies with a rubber chicken, and that was okay. It was more than okay. It was, for a small, lucky audience, perfect.

Final Verdict: 8/10 – A cult classic of anarchic design, sacrificed on the altar of its own brevity and uncompromising, off-kilter humor. Essential for adventure connoisseurs and absurdists; a curiosity for all others.