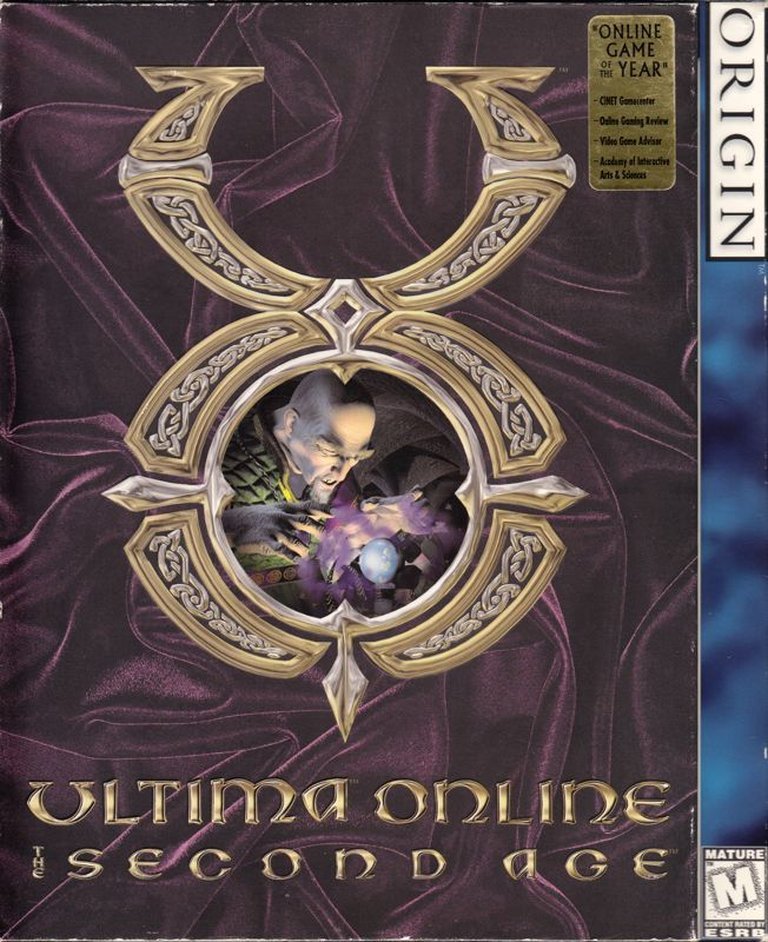

- Release Year: 1998

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: Electronic Arts

- Developer: ORIGIN Systems, Inc.

- Genre: Role-playing (RPG)

- Perspective: Diagonal-down

- Game Mode: Massively Multiplayer

- Setting: Fantasy

- Average Score: 69/100

Description

Ultima Online: The Second Age is the first expansion to the groundbreaking massively-multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG), Ultima Online. Set in the high fantasy world of Britannia, the expansion introduces ‘The Lost Lands,’ a vast new continent for players to explore. This new landmass is filled with fresh challenges, including new dungeons, monsters, and adventures, expanding the original game’s sandbox environment. The expansion also added key social features, most notably an in-game chat system, to enhance player interaction within this persistent, real-time world.

Gameplay Videos

Guides & Walkthroughs

Reviews & Reception

gamepressure.com (65/100): Ultima Online: The Second Age is the first official extension to the Ultima Online MMORPG.

metacritic.com (73/100): The Second Age adds some nice new features and fixes a few things, but it introduces a whole slew of its own problems.

Ultima Online: The Second Age: A Monumental Expansion That Defined an Era

In the annals of MMORPG history, few titles command the reverence and nostalgia of Ultima Online. Its first expansion, The Second Age, released in 1998, stands not merely as an add-on but as a pivotal chapter that solidified the game’s legacy, for better and for worse. It was a testament to ambition, a response to a burgeoning community, and a harbinger of the genre’s future struggles and triumphs.

Introduction: The Dawning of a New Era

When Ultima Online launched in 1997, it didn’t just create a game; it forged a digital society. The Second Age, arriving just a year later, was tasked with an impossible mandate: to satisfy a player base that had already reshaped Britannia in its image. This expansion, often affectionately abbreviated to T2A, was less a narrative sequel and more a foundational update—a doubling down on the sandbox philosophy that made the original revolutionary. Its thesis was simple yet profound: provide more. More land, more monsters, more tools, and more freedom. But in doing so, it also inherited and, in some cases, exacerbated the original’s most vexing problems. The Second Age is a fascinating study in early MMORPG expansion philosophy—a blend of visionary design and pragmatic iteration that left an indelible mark.

Development History & Context: Visionaries Under Pressure

By 1998, Origin Systems, under the aegis of Electronic Arts, was riding a wave of unprecedented success. Ultima Online had proven that persistent online worlds were not just viable but wildly addictive. The team, led by Executive Producer Jeffrey Anderson and Executive Designer Richard Garriott (Lord British himself), was a who’s who of gaming visionaries. Producer/Director Richard Vogel and Lead Designer Raph Koster helmed a crew of 69 credited individuals, many of whom had cut their teeth on the original UO and other landmark titles like Wing Commander: Prophecy.

The technological constraints were severe. In an era of dial-up modems and limited server infrastructure, every new asset and system had to be meticulously optimized. The gaming landscape was equally pressurized. The shadow of impending 3D MMORPGs loomed large; EverQuest and Asheron’s Call were mere months from release, promising a graphical fidelity UO’s isometric 2D could not match. Origin’s response was not to pivot to 3D but to deepen the simulation. The Second Age was developed in “close consultation with the player community,” as noted by German magazine GameStar, a radical approach at the time. This was not a top-down development process but a dialogue, albeit one fraught with the challenges of meeting fan expectations while adhering to technical realities.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: Lore as a Backdrop for Emergence

Unlike modern narrative-driven expansions, T2A did not introduce a grand, linear storyline. Instead, it wove its new content into the existing tapestry of Ultima lore with a light touch. The expansion’s central narrative device was the “Lost Lands,” a continent supposedly unearthed by the geological chaos following the casting of the “Armageddon” spell by the in-game cult, the Followers of Armageddon (or Zog Cabal). This provided a thin but serviceable pretext for new exploration.

The two new towns, Papua and Delucia, were designed as cultural microcosms. Papua, the “Swamp City,” drew direct inspiration from the grass huts and marshlands of Papua New Guinea, populated by NPCs offering essential services. Delucia, the “City of Ruins,” evoked a more classical, decayed fantasy aesthetic with its cotton fields and mineable mountains. These were not hubs for epic quests but sandboxes for player activity. The dialogue and characters were functional, existing to facilitate trade and services rather than to unfold a plot.

Thematically, T2A reinforced Ultima Online’s core principles: player agency and emergent narrative. The expansion’s “story” was the story players created within it—guild wars in the new dungeons, economic empires built around new resources, and the social dramas facilitated by the new chat system. This was a world where themes of conflict, community, and survival were not scripted but born from interaction. The lack of a formal quest system, criticized by reviewers like The Adrenaline Vault, was not an oversight but a philosophical choice. The theme was the player’s own journey.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: Iteration and Imperfection

The core gameplay loop of skill grinding, monster hunting, and player-versus-player conflict remained unchanged. T2A’s genius lay in its expansion of these systems, not their alteration.

- The Lost Lands: This new continent was the centerpiece. With 11 access points via foot, mount, boat, or teleportation, it offered a vast, untamed wilderness. Dungeons like Terathan Keep introduced new high-level challenges, while the open world was populated with a bestiary of 31 new creatures and monsters. From the lowly Bullfrog to the terrifying Wyvern and Titan, these foes were tailored to specific biomes, encouraging exploration and specialization.

- Player Housing & Cities: A landmark addition was the support for player-built cities. This wasn’t just cosmetic; it allowed guilds to establish territorial control, creating a new layer of geopolitical strategy and conflict.

- The Chat System: Perhaps the most quality-of-life impactful feature was the introduction of a dedicated chat interface. This finally moved player communication beyond the rudimentary text commands of the original, facilitating easier socialization and guild coordination.

- SYSTRAN Integration: In a staggering innovation for 1998, T2A integrated SYSTRAN’s real-time machine translation software for English, Japanese, and German. Executive Producer Jeff Anderson hailed it as a tool to “start reaching beyond language barriers,” a bold, early attempt at truly globalizing an online community.

- The Unchanged Core: Critics were united in noting that the expansion did little to address fundamental issues. The notorious “tank-mage” character meta, player killing (PKing), griefing, server lag, and crashes persisted. As GameSpot bluntly put it, the expansion “introduces a whole slew of its own problems” alongside its fixes. The balance between catering to hardcore PvPers and nurturing a broader community remained elusive.

The UI received an update with the “Big Window” mode, offering a larger viewport, but the core interface remained complex and unwieldy by modern standards. Character progression was still a grueling grind of repetitive action, a design choice that PC Joker accurately described as making UO “almost a life’s task.”

World-Building, Art & Sound: A Pixelated Masterpiece

T2A’s art direction, led by Brendon Wilson, was a masterclass in evocative pixel art. The new environments were richly detailed: the oppressive swamps of Papua, the arid ruins of Delucia, and the icy caves housing Frost Trolls each had a distinct identity. The visual design of new creatures like the serpentine Ophidians and the spider-like Terathans was instantly iconic, leveraging the limited palette to create memorable and fearsome foes.

The sound design, by Joe Basquez and Bill Munyon, continued the original’s strong work. The cacophony of combat—the clang of steel, the sizzle of spells, the death cries of monsters—was perfectly integrated into the world. The ambient sounds of the wilderness sold the fantasy of a living, breathing world. While no orchestral score accompanied exploration, the soundscape was a critical, often overlooked, component of immersion.

The overall atmosphere was one of danger and opportunity. The Lost Lands felt genuinely untamed, a frontier where law was dictated by players, not NPCs. This contributed directly to the experience, fostering both a sense of awe and palpable tension—every corner could hide a priceless resource or a lethal ambush.

Reception & Legacy: A Divisive Foundation

Upon its release on October 29, 1998 (with a European delay until June 1999), critical reception was mixed but leaning positive. It holds a 77% average from critics on MobyGames. Publications like PC Zone (92%) praised its endless depth and community, calling it “the first truly amazing multiplayer game.” PC Player (85%) appreciated the new breathing room and variety it offered to veterans.

However, the dissenting voices were telling. GameSpot (63%) and The Adrenaline Vault (70%) criticized its failure to address core problems, with Electric Games (60%) lamenting that “lag, crashes, and antisocial behavior still have not been properly addressed.” The expansion was caught in a catch-22: it was a “no-brainer” for existing players at its low upgrade cost, but a harder sell for newcomers with next-gen competitors on the horizon.

Despite this, its legacy is immense. The Second Age won the “Online Role-Playing Game of the Year” at the 1999 Interactive Achievement Awards (D.I.C.E.). More importantly, it set the template for the MMORPG expansion pack: new continents, new monsters, and new systems. Its player-driven city building foreshadowed features in games like EVE Online. Its attempt at real-time translation was a visionary, if imperfect, push toward a global gaming community. The very problems it failed to solve—PvP balance, toxic behavior, technical instability—became the central challenges the entire genre would grapple with for decades.

Conclusion: The Complicated Pillar of a Genre

Ultima Online: The Second Age is not a flawless masterpiece. It is a messy, ambitious, and deeply human creation. It reflected the best of its developers’ ideals: a belief in player freedom, a commitment to community feedback, and a willingness to innovate technologically. It also reflected their limitations, unable to fully tame the chaotic world they had unleashed.

Its place in video game history is secure as a foundational text. It demonstrated how to expand a persistent world, how to deepen a sandbox, and how to foster a community that would, in turn, define the game itself. It was the last Ultima Online expansion helmed by Raph Koster, and it marks the end of an era of pure, unadulterated sandbox ambition before the genre began its long march toward more structured, theme-park design. For all its flaws, The Second Age remains a towering achievement—a testament to a time when online worlds were wild, unpredictable, and utterly magical.