- Release Year: 2003

- Platforms: Windows

- Publisher: ValuSoft, Inc.

- Developer: GameAgents Corp

- Genre: Educational, Puzzle

- Perspective: Top-down

- Game Mode: Single-player

- Gameplay: 3D mode, Cards, Tiles

- Setting: City, Colonial, Desert, Dungeon, Space, Warehouse

Description

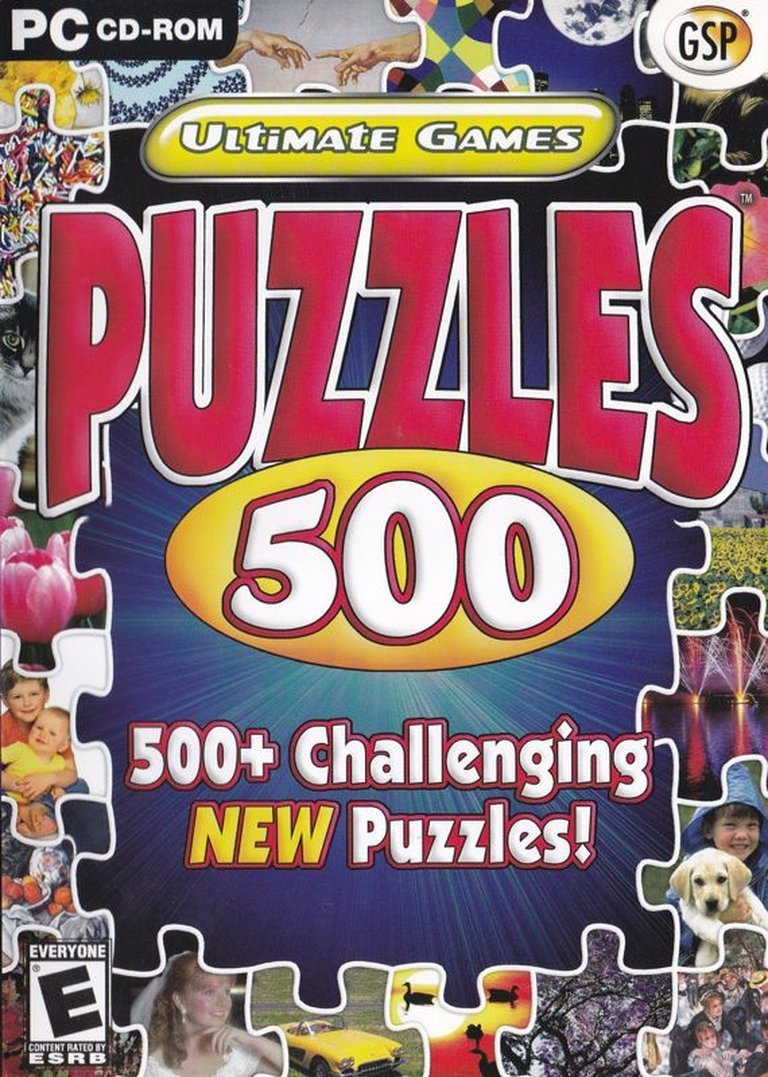

Ultimate Puzzles 500 is a fast-paced jigsaw puzzle game where players race against the clock to reassemble shattered images selected from numerous built-in categories like Flora, Landscape, and Fractal, or imported from personal files. Set in themed worlds such as City, Colonial, Desert, Dungeon, Space, and Warehouse, the game offers both 2D textured backgrounds and immersive 3D modes with dynamic camera angles and detailed environmental models for a versatile single-player experience.

Ultimate Puzzles 500: The Digital Clearance Bin Masterpiece

Introduction: A Quiet Monarch of the Budget Aisle

In the vast, often-overlooked museum of video game history, some titles are enshrined for their revolutionary mechanics, their earth-shattering narratives, or their technical prowess. Others, however, earn their place through sheer, unadulterated persistence. Ultimate Puzzles 500 (2003) is one such title—a game you likely encountered not with fanfare, but in the dimly lit, bargain-basement software aisle of a big-box retailer, its box promising hundreds of puzzles for a price that seemed too good to be true. This review argues that Ultimate Puzzles 500 is a critical artifact of its era: a pure, unapologetic execution of a singular design philosophy that bridged the gap between the tangible satisfaction of a physical jigsaw puzzle and the convenience of digital software. It represents the zenith (and perhaps the endpoint) of the early-2000s “budget compilation” genre, offering a no-frills, mechanically sound experience that speaks volumes about the gaming landscape of its time and the enduring, timeless appeal of puzzle-solving itself.

Development History & Context: The Age of the Bargain Bin

The Studio and the Vision

Developed by GameAgents Corp and published by the aptly named ValuSoft, Inc., Ultimate Puzzles 500 emerged from a specific ecosystem. ValuSoft was a specialist in budget-priced, family-friendly software, frequently licensing properties or creating simple compilations for retail shelves. GameAgents Corp, based on scant available credit information, was a small-scale developer aligned with this value-oriented model. Their vision, as deduced from the final product, was not one of innovation but of accessibility and volume. The goal was to create a competent, feature-rich jigsaw puzzle simulator that could be sold for under $20, appealing to non-gamers, seniors, parents, and anyone seeking a quiet, cognitive pastime on their PC. There was no pretense of narrative or high-concept gameplay; the intent was explicitly stated in its classification on gameclassification.com: an Educational title with purposes of “Educative message broadcasting,” targeting audiences from ages 3 to 25 and the “General Public.”

Technological Constraints and the Gaming Landscape

The year 2003 was a pivotal moment for PC gaming. The industry was in the awkward adolescence between the powerful, fixed hardware of the console PS2/Xbox era and the burgeoning, yet unstandardized, landscape of digital distribution (Steam launched in 2003 but was not yet dominant). Retail was still king, and the “value” or “budget” section was a critical sales channel. Technologically, the game’s features were a direct product of the time:

* 3D Mode: The ability to switch to a 3D environment with “advanced camera angles and movement” was a significant selling point for a puzzle game in 2003. It leveraged the increasingly capable 3D acceleration of mainstream PCs (GeForce 4/Radeon 9700 era) not for complex gameplay, but for atmospheric window dressing. The “worlds” (City, Dungeon, Space, etc.) feature static 3D models, a low-overhead way to create visual variety.

* CD-ROM Distribution: The game was distributed on a single CD-ROM (as seen on the Internet Archive and eBay listings), a format nearing its end but still standard for budget software. The 146.7MB file size was modest, achieved through low-resolution textures and compressed image assets.

* The “500” in the Title: The number 500 was a marketing benchmark. In an era before downloadable content (DLC) and massive online stores, a number of that magnitude in the title signaled immense value—a complete, self-contained library. It directly competed with physical jigsaw puzzle boxes boasting “500 Pieces!” but with the added digital advantages of no lost pieces and variable difficulty.

This placed Ultimate Puzzles 500 in the lineage of PC compilation games like Microsoft Entertainment Packs or Sierra’s Classic Games, but with a more focused, modern sheen. It existed in the shadow of narrative-driven puzzle adventures like Myst (1993) and the rising indie wave that would later push the genre’s boundaries (as noted in the “Evolution of Puzzle Games” article), but its purpose was fundamentally different: relaxation, not revelation.

Narrative & Thematic Deep Dive: The Elegance of Absence

To discuss the narrative of Ultimate Puzzles 500 is to discuss its deliberate and total lack thereof. This is not a game with a plot, characters, or dialogue. Its thematic depth is embedded in its mechanics and presentation, making its “story” one of pure process and personal triumph.

The Core Narrative Loop: The Player vs. The Self

The game’s entire narrative structure is a solitary, cyclical journey: Selection → Revelation → Scattering → Reconstruction → Recorded Triumph. There are no villains, no lore, no exposition. The only antagonist is time, and the only companion is the player’s own past performance (“best time”). This creates a meditative, almost zen-like experience. The moment the player sees the whole image before it “smashes apart” is a fleeting promise of order. The subsequent chaos of pieces is a controlled anarchy to be conquered through pattern recognition, spatial reasoning, and patience—classic cognitive skills aligned with its “Math / logic” and “Graphics / art” educational tags.

Thematic Resonance of the “Worlds”

The choice of a “world” (City, Colonial, Desert, Dungeon, Space, Warehouse) is the game’s only nod to environmental storytelling. These are not settings with stories but aesthetic containers. A “Dungeon” world features stone textures and perhaps a static 3D torch or crate, imbuing the puzzle—which could be a bouquet of flowers (from the “Flora” category)—with a faint, incongruous atmosphere. This juxtaposition is telling. The theme is purely superficial, a coat of paint on an abstract activity. It suggests that the act of puzzling is the universal constant; the context is interchangeable flavor. This reflects a broader theme in casual game design: the primacy of the core loop over any fictional dressing.

The Ultimate Theme: Ownership and Personalization

The game’s most profound thematic statement is its support for custom image import. This transforms the game from a curated collection into a personal archive. The player can piece together a family photo, a vacation snapshot, or a favorite artwork. The puzzle then becomes a tactile reconstruction of memory and meaning. The “best time” for a puzzle of your child’s face carries a weight the pre-set images of “Fireworks” or “Material” can never hold. In this single feature, Ultimate Puzzles 500 transcends its status as a generic compilation and becomes a tool for personal nostalgia and connection—a quiet, digital mirror of the physical tradition of framing a completed puzzle.

Gameplay Mechanics & Systems: A Study in Refined Simplicity

The Core Loop: A Triumph of Focus

The gameplay is exquisitely, purposefully narrow. From the main menu, the player selects:

1. An Image Category (Classic, Fireworks, Flora, Fractal, Landscape, Marine, Material, Microscope, Sunset, Things, Trees).

2. A Specific Image from that category.

3. A Piece Count (implied to range from easier, smaller counts up to the formidable 1000-piece challenges, as per eBay listings mentioning “1000-piece mind benders”).

4. A “World” Environment (City, Colonial, Desert, Dungeon, Space, Warehouse).

5. A Mode (2D or 3D).

The loading screen is a final glimpse of the solved image. With a satisfying crunch (or perhaps a digital shatter), it explodes into its constituent pieces, scattered randomly over the chosen environment. The controls are limited to mouse-driven click-and-drag for piece selection and placement, with optional keyboard shortcuts likely for rotation. The only feedback is the auditory “click” of a piece snapping correctly into place and the visual alignment. There is no line-of-sight highlighting, no “snap-to-grid” aid beyond the inherent shape fitting, and no hint system. This is pure, unassisted jigsaw puzzling. The “real-time” pacing means the clock is always running, adding a layer of pressure for those who desire it, though players can presumably pause or ignore the timer.

Innovation and Flaws: A Double-Edged Sword

Ultimate Puzzles 500’s innovations are subtle but significant for its category:

* The 3D Mode as Ambient Theater: This is its standout feature. Switching to 3D doesn’t change the puzzle mechanics but dramatically alters the sensory experience. The puzzle floats in a 3D space. The camera can be rotated and zoomed, and the themed “world” objects (a streetlamp in City, a cactus in Desert) are visible. This transforms the activity from a flat, 2D desktop task into a quasi-immersive diorama. It’s a low-cost way to make each session feel fresh.

* The Ultimate Feature: Custom Images. As discussed, this elevates the game from a product to a platform. Its implementation is simple but effective, pulling from the user’s file system and automatically processing the image into a puzzle. This feature alone ensures near-infinite replayability.

Its flaws are equally born of its budget, minimalist design:

* Zero Progression or Meta-Game: There are no unlockables, no achievements (outside of personal best times), no narrative to complete, no “game” in the traditional sense. For a modern audience raised on meta-progression, this can feel empty. It is a pure tool disguised as a game.

* Repetitive Aesthetic: While the 500+ pre-set images offer variety, the user interface, piece shapes, and sounds are uniform. The charm of the 3D worlds wears thin as they are largely passive backdrops.

* Limited Interaction: The pieces are manipulated as a single layer. There is no ability to separate edge pieces, flip pieces over, or use multiple “boards.” Advanced puzzle solvers may find the interface constraining compared to modern digital puzzle apps.

World-Building, Art & Sound: Atmosphere as an Afterthought

Visual Direction and Setting

The game’s visual identity is bifurcated. The puzzle images themselves are the star. The categories suggest a library of stock photography and licensed artwork, likely low-to-medium resolution to fit the CD-ROM. Categories like “Fractal” and “Microscope” hint at a desire for visual variety and intellectual curiosity, not just landscapes and animals. The quality is functional, sufficient for puzzle-solving at typical viewing distances.

The “world” environments are where the game’s early-2000s budget aesthetic is most apparent. In 2D mode, they are tiled textures. In 3D, they are simple, low-polygon models (a single building, a palm tree, a simple spacecraft) placed around a void. They are charming in their simplicity, evoking the aesthetic of screensavers or early 3D modeling demos. Their purpose is not realism but suggestion—a lightweight theme to mildly engage the periphery of the player’s attention while their focus remains on the puzzle grid.

Sound Design: The Unseen Support System

Sound is minimal and Functional. Expect a simple, perhaps MIDI-based, looping menu track. The primary audio feedback is the crucial, crisp click of a piece locking into place—the single most important sound in any puzzle game, as it provides instant, satisfying validation. Ambient sounds may differ slightly between 3D worlds (a distant city hum, a desert wind), but they are non-intrusive and easily ignored or muted. The sound design’s success lies in its non-interference; it supports concentration rather than attempting to immerse or excite.

The sum of these parts creates an atmosphere of calm utility. It is not a world to get lost in, but a space to be productive in. The visual and audio design prioritizes cognitive load management over sensory overload.

Reception & Legacy: The Silent Success of the Masses

Critical and Commercial Reception at Launch

Ultimate Puzzles 500 exists in a critical vacuum. It received no professional reviews on major outlets like IGN (which has a placeholder page with “NR” rating) or Kotaku (which has no specific content on it). Its MobyGames entry has a single user rating of 4.3/5, but zero written reviews. This is the hallmark of atrue “clearance bin” game: it was not reviewed by the press because it was not targeting the “gamer” audience the press served. Its commercial success was likely measured in steady, unspectacular sales through retailers like Walmart, Best Buy, and office supply stores. It was a product you bought with a gift card or on a whim, not one you pre-ordered. Its presence on eBay and the Internet Archive decades later is its true legacy—a testament to its physical distribution and the fact that thousands of copies were produced and sold.

Evolution of Reputation and Industry Influence

Its reputation has not so much evolved as it has been re-contextualized. In the early 2000s, it was one of dozens of similar “500 Puzzles” titles (see related games like Ultimate Solitaire 500). Today, it is a nostalgic artifact for a specific segment of players who grew up with a family PC and encountered it in a stack of discs. Its influence is not seen in game design but in market structure:

* It is a direct predecessor to the modern digital “bundle” of puzzles on platforms like Steam (e.g., Puzzling Places, Pixel Puzzles Ultimate) and the endless libraries of mobile puzzle apps.

* It demonstrated the viability of the “infinite content” model via custom image import, a feature now standard in digital puzzlers.

* It represents the last gasp of a certain type of retail software: the low-cost, high-volume, genre-specific compilation that required no installation beyond a CD-ROM, no online account, and no updates. It was a complete product on a disc.

Comparing it to the evolution chart in the “Evolution of Puzzle Games” article, it sits at a strange crossroads. It post-dates the narrative puzzle boom of Myst and pre-dates the indie innovation of Braid and the mobile revolution of Candy Crush. It is a pure, sterile descendant of the physical jigsaw puzzle, unaffected by the genre’s experimental trends. Its legacy is not one of influence but of documentation—it perfectly captures a specific, commercially-driven approach to digital casual gaming that prioritized volume and simplicity above all else.

Conclusion: A Perfectly Competent Time Capsule

Ultimate Puzzles 500 is not a great video game by any conventional critical metric. It has no story, no innovation in gameplay, no artistic vision, and no cultural impact. To judge it as such is to miss the point entirely. As a historical document, however, it is fascinating and successful.

It is a flawless execution of a narrow brief: to digitally replicate the experience of a high-quality, 500-piece jigsaw puzzle collection with the added benefits of no lost pieces, adjustable difficulty, and custom images. Its 3D mode was a clever, low-cost way to add sensory variety within technical limits. Its interface is intuitive and unobtrusive. For the person in 2003 who wanted to piece together a picture of a sunset or their kid’s birthday party without clearing the dining room table, it was a perfect solution.

Its place in video game history is not on a pedestal but in a display case. It is an exemplar of the early-2000s PC value software market—a market of tangible goods sold in physical stores to a non-core audience. It stands as a quiet rebuke to the notion that all games must aspire to be art or epic narratives. Some games are simply tools for quiet occupation, and Ultimate Puzzles 500 is a perfectly serviceable, historically representative tool from a bygone era of retail software. It is the digital equivalent of a solid, no-nonsense 500-piece puzzle bought from a department store: not heirloom quality, but thoroughly functional, and for the right person at the right time, utterly sufficient. Its legacy is that it worked, it sold, and it was forgotten by the mainstream, which is perhaps the most common fate for the vast majority of games ever made. In its own humble category, it was, and remains, ultimately adequate.